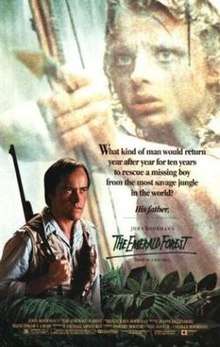

The Emerald Forest

| The Emerald Forest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | John Boorman |

| Produced by |

John Boorman Michael Dryhurst Edgar Gross |

| Written by | Rospo Pallenberg |

| Starring | |

| Music by |

Brian Gascoigne Junior Homrich |

| Cinematography | Philippe Rousselot |

| Distributed by | Embassy Pictures |

Release date | 5 July 1985 |

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language |

English Portuguese |

| Box office | $24,468,550 |

The Emerald Forest is a 1985 British drama film set in the Brazilian Rainforest, directed by John Boorman, written by Rospo Pallenberg, and starring Powers Boothe, Meg Foster, and Charley Boorman with supporting roles by Rui Polanah, Tetchie Agbayani, Dira Paes, Estee Chandler, and Eduardo Conde. It is allegedly based on a true story, although some dispute this. The film was screened out of competition at the 1985 Cannes Film Festival.[1] In promoting the film for awards competition, Boorman created the first Oscar screeners, but the film received no Academy Award nominations.[2]

Plot summary

Bill Markham (Powers Boothe) is an engineer who has moved to Brazil with his family to work on a large hydro-electric dam. The film opens on Markham, his wife Jean (Meg Foster), his young son Tommy (William Rodriguez), and his daughter Heather (Yara Vaneau) having a picnic on the edge of the jungle, which is being cleared for the dam's construction. Tommy wanders from the cleared area, and an Indian (Rui Polanah) from one of the indigenous tribes known as the Invisible People notices Tommy and abducts him. Markham pursues the pair into the forest but does not find his son.

Ten years later, the dam is nearing completion. A 17-year-old Tommy (Charley Boorman), now called Tomme, has become one of the Invisible People. Tomme marries a woman named Kachiri (Dira Paes) and undergoes a vision quest, where his spirit animal tells him he must retrieve sacred stones from a remote spot deep in the jungle. Chief Wanadi, the man who abducted and adopted Tommy, warns him that the quest will be dangerous, as it will take him into the territory of the cannibalistic Fierce People.

Meanwhile, Markham has finally identified his son's abductors. Markham and a journalist decide to set off bottle rockets to attract the attention of the Invisible People. Instead, they attract the Fierce People and are captured. Armed with a CAR-15 carbine, Markham is able to defend himself long enough to talk with Chief Jacareh (Claudio Moreno) who releases Markham for the night, promising to hunt him down in the morning, while the Fierce People kill and butcher the journalist. Close to dawn, Markham stumbles into Tomme collecting the sacred stones. The two recognize each other just as the Fierce People arrive, shooting Markham in the shoulder. Tomme and his father manage to escape, leaving Markham's carbine behind. In the care of the Invisible People, Markham recovers from his injuries and undergoes a vision quest, waking up back at the dam's construction zone.

Jacareh, recognizing the destructive power of Markham's carbine, visits a seedy brothel at the edge of the construction zone and arranges to exchange women for ammunition and more guns. Tomme and his friends return to their village to discover that many of the Invisible People have been murdered and all the young women abducted by the Fierce People. Desperate for help, Tomme navigates the city to his parents' condo, and Markham agrees to help rescue the women from the brothel.

That night, Markham initiates a shootout in the brothel while Tomme and his friends release the enslaved women from captivity. In the ensuing battle, the Fierce People kill several members of the Invisible People, including Chief Wanadi. Tomme is later sworn in as the new chief of the tribe. Markham warns Tomme that the almost-completed dam will end the tribe's way of life, but Tomme insists that the Invisible People are safe. During a storm, Markham places demolition explosives at key points along the dam, blowing it up.

The film ends with Tomme and Kachiri sitting at the swimming hole near their village in the jungle, watching the members of their tribe splash and play.

Cast

- Powers Boothe as Bill Markham

- Meg Foster as Jean Markham

- Charley Boorman as Tomme/Tommy Markham

- William Rodriguez as Young Tommy Markham

- Estee Chandler as Heather Markham

- Yara Vaneau as Young Heather Markham

- Dira Paes as Kachiri

- Eduardo Conde as Uwe Werner

- Ariel Coelho as Padre Leduc

- Peter Marinker as Perreira

- Mario Borges as Costa

- Átila Iório as Trader

- Gabriel Archanjo as Trader's Henchman

- Gracindo Júnior as Carlos

- Arthur Muhlenberg as Rico

- Chico Terto as Paulo

- Claudio Moreno as Jacareh

Invisible Tribe

- Rui Polanah as Wanadi

- Maria Helena Velasco as Uluru

- Tetchie Agbayani as Caya

- Paulo Vinicius as Mapi

- Aloiso Flores as Samanpo

- Joao Mauricio Ca as Monkey

- Isabel Bicudo as Kachiri's cousin

- Patricia Prisco as Kachiri's cousin

- Silvana de Faria as Pequi

Reception

As of 2018, Rotten Tomatoes assigns it an 81% approval rating out of 16 reviews.[3] The Emerald Forest was designated a Critics' Pick by a New York Times reviewer, who called it "compelling and richly atmospheric".[4] In a negative review, Paul Attanasio of the Washington Post called it "long, wheezy tribute to the Noble Savage" and more of "a National Geographic special" than a proper film.[5]

It was nominated for 3 BAFTA Awards, for Cinematography, Make Up, and Score.

Inspiration

The film was promoted as "based on a true story". Critic Harlan Ellison in his book Harlan Ellison's Watching wrote that attempts by SCAN[6] to get background information on the real story revealed that Rospo Pallenberg's original screenplay was based on several stories,[7] including an article in the Los Angeles Times about a Peruvian labourer whose child had been abducted by a local Indian tribe and located sixteen years later almost fully assimilated.[8] Pallenberg's agent told SCAN that while director John Boorman had said that he read the original L.A. Times article, in fact, he had not, but was simply working from Pallenberg's screenplay. According to SCAN, Boorman told NPR's All Things Considered that the son was still living with the tribe in 1985, and identified the tribe as "the Mayoruna", yet detailed anthropological studies of that tribe do not mention an adopted outsider.[7]

An additional possible source for The Emerald Forest is the book, Wizard of the Upper Amazon, first published before 1975.[9] The story is an account of Manuel Cordova-Rios’ kidnapping when he was a teenager working for rubber cutters in the Amazon in the early 1900s. He was taken by a group of Native Amazonians to their remote Indian village. These Amazonians were fiercely independent and had fled into the interior because they refused to live under the subservient conditions imposed by the rubber barons at that time. Cordova-Rios was incorporated into their tribe and describes a life strikingly similar to the one depicted in The Emerald Forest.[9][10]

Contrary to Ellison's conclusion, a contemporaneous January 1985 review in Variety magazine states up front that the movie is "[b]ased on an uncredited true story about a Peruvian whose son disappeared in the jungles of Brazil."[11] The Los Angeles Times article also mentioned that the Peruvian child had at the time decided as an adult to stay with his adoptive tribe.[8]

First Oscar screeners

Because Embassy Pictures was struggling in the year of Emerald Forest's release, the film did not receive a traditional "For Your Consideration" advertising campaign for the 1985 Academy Awards. Boorman took the initiative to promote the film himself by making VHS copies available for no charge to Academy members at several Los Angeles-area video rental stores. Boorman's idea later became ubiquitous during Hollywood's award season, and by the 2010s, more than a million Oscar screeners were mailed to Academy members each year. However, Emerald Forest itself received no nominations from Boorman's strategy.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: The Emerald Forest". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- 1 2 Miller, Daniel (March 1, 2018). "The Oscar screener was invented by accident, and other secrets of an awards season staple". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

"The Emerald Forest" didn't get any Oscar nominations — but Boorman's gambit made an impact: He effectively invented the movie screener, now an integral part of Hollywood's awards season apparatus.

- ↑ "The Emerald Forest". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ↑ "New York Times' Critics' Picks". New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ↑ Attanasio, Paul (July 3, 1985). "It's Rough in the Jungle". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ↑ The Southern California Answer Network (SCAN) is a library reference / research company.

- 1 2 Ellison, Harlan (1989). Harlan Ellison's Watching. Underwood. pp. 407–409.

- 1 2 Greenwood, Leonard (8 October 1972). "Long hunt for son ends in success, but —". Los Angeles Times. p. 10. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010.

- 1 2 Cordova-Rios, Manuel (1975). Wizard of the upper Amazon: The story of Manuel Cordova-Rios (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395199190.

- ↑ Cordova-Rios, Manuel; Lamb, F. Bruce (1993). Wizard of the upper Amazon: The story of Manuel Cordova-Rios (3rd Revised ed.). North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0938190806.

- ↑ "The Emerald Forest". Variety. 1 January 1985. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

Further reading

- Holdstock, Robert (1985). John Boorman's the Emerald Forest. New York Zoetrope. ISBN 978-0-918432-70-4.

- Boorman, John (1985). Money into Light: The Emerald Forest Diary. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-14769-3.

External links

- Listen to John Boorman discussing The Emerald Forest – a British Library recording.

- The Emerald Forest on IMDb

- The Emerald Forest at Box Office Mojo

- The Emerald Forest at Rotten Tomatoes