The Devils (film)

| The Devils | |

|---|---|

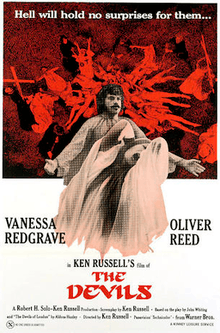

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Russell |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Ken Russell |

| Based on |

The Devils of Loudun by Aldous Huxley The Devils by John Whiting |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Peter Maxwell Davies |

| Cinematography | David Watkin |

| Edited by | Michael Bradsell |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

The Devils is a 1971 British historical drama horror film directed by Ken Russell and starring Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave. Russell's screenplay is based partly on the 1952 book The Devils of Loudun by Aldous Huxley, and partly on the 1960 play The Devils by John Whiting, also based on Huxley's book.

The film is a dramatised historical account of the rise and fall of Urbain Grandier, a 17th-century Roman Catholic priest executed for witchcraft following the supposed possessions in Loudun, France. Reed plays Grandier in the film and Vanessa Redgrave plays a hunchbacked sexually repressed nun who finds herself inadvertently responsible for the accusations.

The film faced harsh reaction from national film rating systems due to its disturbingly violent, sexual, and religious content, and originally received an X rating in both the United Kingdom and the United States. It was banned in several countries, and eventually heavily edited for release in others. The film has never received a release in its original, uncut form in various countries, and is largely unavailable in the home video market.

Plot

- Note: This plot is for the unedited version of the film. Some scenes described below are omitted from other versions.

In 17th Century France, Cardinal Richelieu is influencing Louis XIII in an attempt to gain further power. He convinces Louis that the fortifications of cities throughout France should be demolished to prevent Protestants from uprising. Louis agrees, but forbids Richelieu from carrying out demolitions in the town of Loudun, having made a promise to its Governor not to damage the town.

Meanwhile, in Loudun, the Governor has died, leaving control of the city to Urbain Grandier, a dissolute and proud but popular and well-regarded priest. He is having an affair with a relative of Father Canon Jean Mignon, another priest in the town; Grandier is, however, unaware that the neurotic, hunchbacked Sister Jeanne des Anges (a victim of severe scoliosis who happens to be abbess of the local Ursuline convent), is sexually obsessed with him. Sister Jeanne asks for Grandier to become the convent's new confessor. Grandier secretly marries another woman, Madeleine De Brou, but news of this reaches Sister Jeanne, driving her to jealous insanity. When Madeleine returns a book by Ursuline foundress Angela Merici that Sister Jeanne had earlier lent her, the abbess viciously attacks her with accusations of being a "fornicator" and "sacrilegious bitch," among other things.

Baron Jean de Laubardemont arrives with orders to demolish the city, overriding Grandier's orders to stop. Grandier summons the town's soldiers and forces Laubardemont to back down pending the arrival of an order for the demolition from King Louis. Grandier departs Loudun to visit the King. In the meantime, Sister Jeanne is informed by Father Mignon that he is to be their new confessor. She informs him of Grandier's marriage and affairs, and also inadvertently accuses Grandier of witchcraft and of possessing her, information that Mignon relays to Laubardemont. In the process, the information is pared down to just the claim that Grandier has bewitched the convent and has dealt with the Devil. With Grandier away from Loudon, Laubardemont and Mignon decide to find evidence against him.

Laubardemont summons the lunatic inquisitor Father Pierre Barre, a "professional witch-hunter," whose interrogations actually involve depraved acts of "exorcism", including the forced administration of enemas to his victims. Sister Jeanne claims that Grandier has bewitched her, and the other nuns do the same. A public exorcism erupts in the town, in which the nuns remove their clothes and enter a state of "religious" frenzy. Duke Henri de Condé (actually King Louis in disguise) arrives, claiming to be carrying a holy relic which can exorcise the "devils" possessing the nuns. Father Barre then proceeds to use the relic in "exorcising" the nuns, who then appear as though they have been cured – until Condé/Louis reveals the case allegedly containing the relic to be empty. Despite this, both the possessions and the exorcisms continue unabated, eventually descending into a massive orgy in the church in which the disrobed nuns remove the crucifix from above the high altar and sexually assault it.

In the midst of the chaos, Grandier and Madeleine return and are immediately arrested. After being given a ridiculous show trial, Grandier is shaven and tortured – although at his execution, he eventually manages to convince Mignon that he is innocent. The judges, clearly under orders from Laubardemont, sentence Grandier to death by burning at the stake. Laubardemont has also obtained permission to destroy the city's fortifications. Despite pressure on Grandier to confess to the trumped-up charges, he refuses, and is then taken to be burnt at the stake. His executioner promises to strangle him rather than let him suffer the agonising death by fire that he would otherwise experience, but the overzealous Barre starts the fire himself, and Mignon, now visibly panic-stricken about the possibility of Grandier's innocence, pulls the noose tight before it can be used to strangle the priest. As Grandier burns, Laubardemont gives the order for explosive charges to be set off and the city walls are blown up, causing the revelling townspeople to flee.

After the execution, Barre leaves Loudun to continue his witch-hunting activities elsewhere in the southwest of France. Laubardemont informs Sister Jeanne that Mignon has been put away in an asylum for claiming that Grandier was innocent (the explanation given is that he is demented), and that "with no signed confession to prove otherwise, everyone has the same opinion". He gives her Grandier's charred femur and leaves. Sister Jeanne, now completely broken, masturbates pathetically with the bone. Madeleine, having been released, is seen walking over the rubble of Loudun's walls and away from the ruined city as the film ends.

Cast

- Oliver Reed as Father Urbain Grandier

- Vanessa Redgrave as Sister Jeanne of the Angels

- Dudley Sutton as the Baron de Laubardemont

- Max Adrian as Ibert

- Gemma Jones as Madeleine De Brou

- Murray Melvin as Father-Canon Jean Mignon

- Michael Gothard as Father Pierre Barre

- Georgina Hale as Philippe Trincant

- Brian Murphy as Adam

- John Woodvine as Louis Trincant

- Christopher Logue as Cardinal Richelieu

- Kenneth Colley as Legrand

- Graham Armitage as Louis XIII of France

- Andrew Faulds as Rangier

- Judith Paris as Sister Judith

- Catherine Willmer as Sister Catherine

Production

Ken Russell wrote the screenplay based on The Devils of Loudun, a 1952 non-fiction novel by Aldous Huxley and John Whiting's 1961 play The Devils, which itself was based on Huxley's work.[2]

The film's sets of Loudun—which were depicted as a modernistic white-tiled city— were devised by Derek Jarman, who spent three months designing them.[3]

Soundtrack

The film score was composed for a small ensemble by Peter Maxwell Davies.[4] Davies reportedly took the job because he was interested in the late medieval and Renaissance historical period depicted in the film.[5] It was recorded by his regular collaborators the Fires of London with extra players as the score calls for more than their basic line-up.[6] Maxwell Davies' music is complemented by period music (including a couple of numbers from Terpsichore), performed by the Early Music Consort of London under the direction of David Munrow.[7]

Concert suite

The Fires of London and the Early Music Consort of London gave a performance of a concert suite of the music at the Proms in 1974.[8] There have been other performances of music from the film in the concert hall.[9]

Release and censorship

The film's commentary on religious institutions such as the Catholic Church and organised religion in general created controversy with rating and censor boards around the world. Its graphic depictions of violence also accentuated the film's uncompromising subject matter.[10]

The British Board of Film Censors found the film's combination of religious themes and violent sexual imagery a serious challenge, particularly as the Board was being lobbied by socially conservative pressure groups such as the Festival of Light at the time of its distribution.[11] In order to gain a release and earn a British 'X' certificate (suitable for those aged 18 and over), Russell made minor cuts to the more explicit nudity (mainly in the cathedral and convent sequences), details from the first exorcism (mainly that which indicated an anal insertion), some shots of the crushing of Grandier's legs, and the pantomime sequence during the climactic burning. However, the biggest cuts were made by the studio itself, prior to submission to the BBFC. Two notable scenes were removed in their entirety, one was a two-and-a-half-minute sequence of naked nuns sexually assaulting a statue of Christ and another scene showing Sister Jeanne masturbating with the charred femur of Grandier.[12]

The film was released in 'X' form (no one under 18 years of age admitted) for both its UK and US theatrical runs,[13] though the US version was 2 minutes and 42 seconds shorter than the UK theatrical release. All subsequent VHS versions, beginning with the UK release in 1982 all the way up to the 1991 US VHS rerelease, are of the initial US theatrical release. In 1997 Warner Brothers released the longer UK version (110:53) on VHS tape with a partial widescreen, though still clipping the sides.

Critical response

The film remains controversial since the time of its first release in July 1971. In the UK, 17 local authorities banned the film's distribution. Critics gave it equally scathing reviews. Judith Crist called it a "grand fiesta for sadists and perverts", while Derek Malcolm called it "a very bad film indeed." Roger Ebert gave the film a rare zero-star rating.[14]

However, it won the award for Best Director-Foreign Film in the Venice Film Festival, despite being temporarily confiscated in Verona. The film was granted release a few weeks later. The United States National Board of Review awarded Ken Russell best director for The Devils and his next film, The Boy Friend. Film historian Joel W. Finler described The Devils as Russell's "most brilliant cinematic achievement, but widely regarded as his most distasteful and offensive work".[15] In 2002, when 100 film makers and critics were asked to cite what they considered to be the ten most important films ever made, The Devils featured in the lists submitted by critic Mark Kermode and director Alex Cox.[16]

Modern reappraisal

Much of the cut material was presumed to have been lost or destroyed until critic Mark Kermode found a copy of the complete "Rape of Christ" sequence and several other deleted scenes (including the fuller version of Sister Jeanne's masturbation scene as well as additional sequences of naked nuns lounging around the convent and a bawdy dance performed by travelling players mimicking the bizarre events whilst Grandier is being led to his death) in 2002.[17] The artist Adam Chodzko made a video work in which he traced and interviewed many of the actresses who had played the nuns during the orgy scene. Although some material may have been lost forever, the NFT was able to show The Devils in the fullest possible state in 2004. This uncut director's version premiered at the Brussels International Festival of Fantasy Film in March 2006.

On 25 April 2007, The Devils was shown for a second time in its fullest possible state to a group of students and staff at the University of Southampton, followed by a question and answer session with the director, moderated by Mark Kermode. It was the first significant event to take place during Russell's tenure as a visiting fellow at the University of Southampton in the English and film departments, April 2007 – March 2008.

On 19 July 2010, the film was screened for the Fantasia Film Festival in Montreal at the Hall theatre, preceded by a Q & A session with director Ken Russell. It was screened again on 28 July.

On the evening of 20 August 2010, the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles hosted Ken Russell at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica with screenings of The Devils (108-minute version) and Altered States (1980) with Charles Haid and Stuart Baird in attendance. There was a discussion between films with director Russell and actor Charles Haid, and moderated by Mick Garris.

On 29 August 2010, The Devils was again shown at the Bloor Street Cinema in Toronto, Ontario, preceded by a question and answer session with director Ken Russell.

In April 2011, London's East End Film Festival screened the full uncut version, which was claimed to be only the third time this version has been shown in the UK. Ken Russell and other cast were in attendance to take part in a Q&A afterwards.[18]

The British Film Institute released the 111 minute UK theatrical version (sped up to 107 minutes to accommodate the technicalities of PAL colour) on DVD on 19 March 2012. BFI licensed the film from Warner Bros., but was not permitted to include the additional Kermode-found footage from 2004, nor issue the film on Blu-ray.[19] The BFI release also includes the Kermode documentary on the history of the film entitled Hell on Earth: The Desecration & Resurrection of The Devils, as well as a vintage documentary shot during the production entitled Directing Devils. Additionally, the release includes an early Ken Russell short film entitled Amelia and the Angel, which was made shortly after Russell converted to Catholicism.[20][21]

Photographs from a lost Spike Milligan scene, together with Murray Melvin's memories of that day's filming, are included in Paul Sutton's book, 'Six English Filmmakers' (2014, ISBN 978-0957246256).

Home media

An NTSC-format DVD edition of the R-rated version on the Angel Digital label appeared in 2005, with the so-called "Rape of Christ" scene and other censored footage restored, and featuring a documentary by Mark Kermode about the film, as well as interviews with Russell, some of the surviving cast members, and a member of the BBFC who participated in the original censorship of the film.[22]

DVDActive.com announced on 28 February 2008 that The Devils would finally be released on DVD by Warner Home Video in the US on 20 May 2008, in the UK theatrical (111 min) version, but without additional material. However, a day later, a DVDActive forum post asserted that the release had been dropped from Warner's schedule.[23] Warner Bros released The Devils on DVD in Spain in the summer of 2010. However, it was the heavily cut US version. Despite this, the US R-rated version surfaced again on 31 December 2010 as a Euro Cult DVD, with the so-called 'Rape of Christ' scene and some censored footage restored, and with the accompaniment of the above-mentioned interviews as well as commentary by the censors and the US trailer. This claimed-to-be 'uncut' NTSC Euro Cult DVD as available in the US during 2011 actually plays for under 109 minutes even though the packaging claims 111 minutes; it does not include all the missing footage.[22]

In June 2010, Warner Bros. released The Devils in a 108-minute version for purchase and rental through the iTunes Store,[24] but the title was removed without explanation three days later.[25]

In March 2017, streaming service Shudder began carrying the 109-minute US release version of The Devils, but it was taken down several months later. [26] In September 2018, FilmStruck began streaming the same US cut.

See also

- Mother Joan of the Angels – A 1961 Polish film also based on the Loudun possessions.

- The Crucible, ostensibly about Salem witch trials, but actually a political satire that shares several plot parallels with The Devils.

- The Devils of Loudun (opera) by Krzysztof Penderecki, 1968 and 1969; revisions 1972 and 1975.

- Belladonna of Sadness

References

- ↑ Crouse 2012, p. 163.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, p. 33.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, p. 81.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, pp. 81–2.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ "The Devils: composer's note". maxopus.com. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "Proms performances".

- ↑ Hewett, Ivan (2012). "H7steria". Telegraph.

- ↑ Wells, Jeffrey (29 March 2010). "A History of Censorship". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ Robertson, James Crighton (May 1993). The Hidden Cinema: British Film Censorship in action, 1913–1975. Routledge. pp. 139–146.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Case Study: The Devils, Students' British Board of Film Classification page Archived 23 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, pp. 123, 130–31.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "The Devils Movie Review & Film Summary (1971) - Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com.

- ↑ Finler, Joel W. (1985). The Movie Directors Story. London : Octopus Books. p. 240. ISBN 0706422880.

- ↑ Sight and Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 – Who voted for which film: The Devils, British Film Institute

- ↑ Crouse 2012, pp. 169–70.

- ↑ Jeffries, Stuart (28 April 2011). "Ken Russell interview: The last fires of film's old devil". The Guardian.

- ↑ "DVD & Blu-ray". filmstore.bfi.org.uk.

- ↑ "The Devils". rockshockpop.com.

- ↑ "The Devils DVD Review". criterionforum.org.

- 1 2 Crouse 2012, p. 173.

- ↑ "The Devils (US - DVD R1)". dvdactive.com.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Crouse 2012, p. 175.

- ↑ Rife, Katie (March 15, 2017). "Ken Russell's widely banned The Devils makes a surprise appearance on Shudder". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

Works cited

- Crouse, Richard (2012). Raising Hell: Ken Russell and the Unmaking of the Devils. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-770-90281-7.