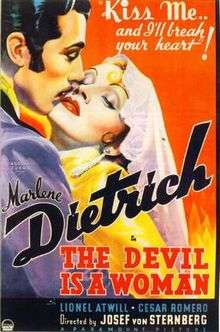

The Devil Is a Woman (1935 film)

| The Devil Is a Woman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Josef von Sternberg |

| Produced by | Josef von Sternberg |

| Screenplay by | John dos Passos |

| Based on |

The Woman and the Puppet 1898 novel by Pierre Louÿs 1910 play by Pierre Louys and Pierre Frondaie |

| Starring |

Marlene Dietrich Lionel Atwill Cesar Romero |

| Music by |

John Leipold Heinz Roemheld |

| Cinematography | Josef von Sternberg |

| Edited by | Sam Winston |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date | 15 March 1935 |

Running time | 76 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Devil Is a Woman is a 1935 romance film directed and photographed by Josef von Sternberg, adapted from the 1898 novel La Femme et le pantin by Pierre Louÿs. The film was based on a screenplay by John Dos Passos, and stars Marlene Dietrich, with Lionel Atwill, Cesar Romero, Edward Everett Horton, and Luisa Espinel. The movie is the last of the seven Sternberg-Dietrich collaborations for Paramount Pictures.

Plot Summary

The story unfolds amidst the festivities of Seville’s Carnival set in the fin de siècle Spain. The events revolve around four characters – there are no subplots.

Concha "Conchita" Perez: a beautiful, piquant and heartless factory girl who seduces and discards her lovers without remorse – an irresistible femme fatale.

Antonio Garvan: a young bourgeois revolutionary, one step ahead of Seville’s police. He is narcissistic, yet good-natured, and lucky with women.

Captain Don Pasqual Costelar: a middle-aged aristocrat and Captain of the Civil Guard. His conservative exterior conceals powerful salacious impulses.

Governor Don Paquito: A minor character. The despotic commander of Seville’s police force, who is responsible for maintaining order during the festivities. Don Paquito is susceptible to the charms of attractive women.[1]

The film’s narrative is presented in four scenes, the second of which contains a series of flashbacks.

_1935_1_-_Lionel_Atwill%2C_Marlene_Dietrich.jpg)

_1935%2C_B-W_movie_stills%2C_L-R%2C_Marlene_Dietrich_(Concha)%2C_Caesar_Romero_(Antonio).jpg)

Scene 1 – The boulevards of Seville are jammed with revelers wearing grotesque costumes, masks and parade sculptures. A detachment of Civil Guards stagger among the masqueraded merrymakers, bewildered by the “riotous disorder”. A frenzied merriment prevails. Antonio Galvan mixes with the crowds, evading the authorities who pursue him. He makes eye contact with the dazzling Concha, who is perched on an garish street float. The coquette flees into throng with Antonio in pursuit: he is rewarded with a secret note inviting him to meet with her in person that evening.

Scene 2 – Antonio has a chance encounter with a friend of years past, Don Pasqual. The younger man, consumed with the image of the lovely Concha, asks the older gentleman what he knows of the mysterious girl. Don Pasqual solemnly relates the details of his fateful relationship with the young temptress in a series of vignettes. His tale is the confession of a man in thrall to the devastating girl. She subjects him to ridicule and humiliation, manipulating Don Pasqual in the manner of a puppet master – to which he submits. His public prestige and authority is shattered and he resigns his commission in disgrace. Satisfied with her conquest, she flings him aside.[2]

Don Pasqual assures Antonio that any desire he has felt for Concha is utterly extinguished. He further exhorts the young man to avoid any contact with the temptress, and Antonio vows to heed his warning.

Scene 3 – Don Pasqual’s cautionary tale has produced the opposite effect on Antonio and he keeps his rendezvous with enigmatic Concha. Alone together in a room at a club nocturne, Antonio confronts her with Don Pasqual’s tale of betrayal. A handwritten note arrives during the interview – a note from Don Pasqual declaring his undying love for Concha. She reads the confidential confession to Antonio, who responses by passionately kissing her. Moments later, Don Pasqual enters their private quarters, where his motivations for lecturing his young rival on the dangers of the devilish Concha are fully exposed. He compounds his duplicity by accusing Antonio of breaking his oath. Concha leaps to Antonio’s defense and insultingly dismisses her erstwhile lover. Don Pasqual slaps Antonio – a formal insult – and a duel is arranged. Don Pasqual departs, after demonstrating his expert marksmanship with a pistol. Concha pledges to accompany Antonio to Paris after the duel.

The suitors meet at a secluded location the following morning. Concha accuses Don Pasqual of threatening to kill “the only man I ever cared for”. When the duelists step to their positions, Don Pasqual declines to discharge his pistol, and is gravely wounded by Antonio’s bullet. The police, notified of the illegal combat, arrive and arrest the fugitive Garvan. Don Paquel is taken to the hospital.

Scene 4 – Concha, desperate to rescue Antonio, turns her charms on Governor Paquito, and obtains his authorization form her lovers release from prison. Paquito gratuitously issues her two passports that will allow them to escape to Paris.

Concha visits the hospital where the mortally wounded Don Pasqual is clinging to life. She acknowledges her debt to her former flame for sparing Antonio’s life; Pasqual spurns her, but she detects that he still adores her.

Concha and Antonia make their way to the border crossing with France and pass customs without incident. The train will depart momentarily, and Antonio eagerly enters their carriage. Concha hesitates, then informs the station master that she is not boarding. When the shocked Antonio calls to her from the window of the moving train, she announces that she intends to rejoin the dying Don Pasqual and she reenters Spain.

Production Notes

Sternberg embarked upon filming The Devil is a Woman at a time when Paramount was experiencing falling profits and his latest and lavishly produced The Scarlet Empress proved unpopular with the public. The film was completed on February 6, 1935 and premiered without fanfare in March. Incoming production manager and director Lubitsch (replacing Ben Schulberg) announced that Sternberg's Paramount contract would not be renewed. In May 1935, The Devil is a Woman was released to general audiences.[3][4]

The original title proposed by Sternberg for the film was Caprice Espagnol, a reference to Russian composer Rimsky-Korsakov's orchestral suirte Capriccio Espagnol, of which several selections accompany the film. Ernst Lubitsch, studio manager at the time, subsequently changed to The Devil is a Woman. [5] Sternberg later remarked, “Though Mr. Lubitsch’s poetic intention to suggest altering the sex of the devil was meant to aid in the selling the picture, it did not do so.”[6]

Approximately seventeen minutes of footage, including a musical number by Dietrich, "If It Isn't Pain (It Isn't Love)", was cut from the film, reducing the total running time to 76 minutes.[7]

Presumed to be a “lost” film, a personal copy of the work was provided by Sternberg for a screening at the 1959 Venice Film Festival. The Devil is a Woman received limited circulation in 1961.[8]

Reception

On May 5, 1935 The New York Times surprised the studio with a remarkably positive review describing the film "as the best product of the Dietrich-Sternberg alliance since The Blue Angel.[9]

_1935_movie_still_B-W_Marlene_Dietrich_as_Concha_Perez.jpg)

The Devil is a Woman is the last of von Sternberg’s seven quasi-autobiographical films that feature his star and muse, Marlene Dietrich.[10] A box office failure, panned by contemporary critics for its perceived “caviar aestheticism and loose morals”, the film’s highly sophisticated rendering of a conventional romantic conceit, left most audiences confused or bored."[11]

_1935._Josef_von_Sternberg%2C_director._Marlene_Dietrich.jpg)

Censorship: Spain and US Department of State

Upon its release, the Spanish embassy issued protests to the US government that led to Paramount’s withdrawal of the film from circulation and destruction of available prints. The US State Department in a show of sympathy - and with Spanish and American trade agreements in mind - pressured Paramount Pictures to stage a private burning of a "Master Print" of the film for the Spanish Ambassador in Washington D.C. The diplomatic action was widely reported in Europe, but distribution of The Devil is a Woman continued at domestic and overseas theatres. [12]

In October of 1935, Spain formerly requested that Paramount cease international circulation of the film. A portion of the complaint cited a scene that showed "a Civil Guard drinking [alcohol] in a public cafe" and depicting the national police, as buffoons, who appeared “ineffectual in curbing the riotous carnival” With US-Spain trade agreements in the balance, studio head Adolph Zukor "agreed to suppress the film" and prints were recalled in November 1935. Sternberg's feature was marked as a film maudit (a cursed film) for many years. The movie was subsequently outlawed in Spain under the Francisco Franco regime.[13][14]

Critical Response

The Devil of a Woman, in its “worldly attitude toward the follies of romantic infatuation” makes a mockery of Hollywood’s standard plot devices that prevailed up to that time.[15] Sternberg acknowledged that it was “my last and most unpopular of this series”, but Dietrich herself cherished The Devil is a Woman as her favorite collaboration with Sternberg.[16] Ostensibly a light romance, the story examines that fate of a self-respecting and urbane older gentleman who foolishly falls in love with a beautiful woman indifferent to his adoration - and suffers for his passion. Sternberg’s “grisly” tale is also a precise, unadorned and “heartless parable of man’s eternal humiliation in the sex struggle.”[17] Dietrich, as a “devilish” and “devastating” Spanish joie de vivre, brandishes her cruelty with the rejoinder “If you really loved me, you would have killed yourself.”[18] The horror and pathos of his figure is that of a man in thrall to a woman who has no intention of satisfying his desires, and who perversely “derives amusement from his own suffering.”[19]

Andre Sennwald, daily reviewer at The New York Times in 1935, defended Sternberg, calling the movie “one of the most sophisticated ever produced in America” and praising its “sly urbanity” and “the striking beauty of its settings and photography.”[20] Museum of Modern Art film curator Charles Silver regards The Devil is a Woman as a veiled confessional of Sternberg’s complex relationship with Dietrich. The leading male protagonists bear a striking physical resemblance to the director.[21]

Sternberg leaves the interpretation of Deitrich’s Concha a mystery: “One of the most beautifully realized enigmas in the history of cinema."[22] Sternberg’s attitude towards his male protagonists is less ambiguous. Both the pathetic old Don Pasqual, and the virile young Antonio, are regarded more with irony and less with sympathy: each are “symbols of the endless futility of passion...[t]hey are the last lovers Sternberg postulated for Dietrich’s screen incarnation and their absurdity only marks the death of desire.”[23]

Film critic Andrew Sarris described The Devil is a Woman as the “coldest” of Sternberg’s films in its uncompromising, yet humorously cynical, appraisal of romantic self-deception. This, despite the film’s “sumptuous surface.”[24] Silver remarks upon the film’s “diamond-like hardness”, where romanticism is trumped by “cynical introspection and fatalism.” [25][26]

Susan Sontag, from her essay "Camp" (1964).[27]

On Dietrich's character, Concha Perez, Cecelia Ager, film critic for Variety was "particularly lucid on the subject":

“Not even Garbo in the Orient has approached, for spectacular effects, Dietrich in Spain….Her costumes are completely incredible, but completely fascinating and suitable to The Devil is a Woman. They reek with glamour…Miss Dietrich emerges as a glorious achievement, a supreme consolidation of the sartorial, make-up and photographic arts.”[28]

Sarris summed up the film this way: "Sternberg did not know it at the time, but his sun was setting, and it has never really risen again...Still, as a goodbye to Dietrich, The Devil is Woman is a more gallant gesture to one’s once beloved than Orson Welles’ murderous adieu to Rita Hayworth in The Lady From Shanghai."[29]

Cast

- Marlene Dietrich as Concha Pérez

- Lionel Atwill as Capt. Don Pasqual Costelar

- Edward Everett Horton as Gov. Don Paquito

- Alison Skipworth as Señora Pérez

- Cesar Romero as Antonio Galvan

Awards and honors

The film won the Award for Best Cinematography at the Venice Film Festival in 1935.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – nominated[30]

References

- ↑ The Film Sufi, 2015.

- ↑ Malcolm, 2000.

- ↑ Baxter, 1971. p. 121, 128

- ↑ Swanbeck, 2013.

- ↑ Baxter, 1971. p. 123

- ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 41

- ↑ Stafford, 2018

"If It Isn't Pain (It Isn't Love)" - YouTube, retrieved 18 April, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FAUdRXn7rGY - ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 41

Stafford, 2018. - ↑ Baxter, 1971. p. 128

- ↑ Silver, 2010. “...a semi-autobiographical films with his star and lover, Marlene Dietrich” and “The Devil is a Woman is something of a translation of the Sternberg/Dietrich relationship into visual poetry and metaphor.”

- ↑ Lopate, XXXX, p.85: It was "...roundly attacked at the time” of its release.

Sennwald, 1935. p. 85: “...Hollywood expressed...violent distaste for Josef von Sternberg’s new film” and was “disliked by nine-tenths” of moviegoers. - ↑ Baxter, 1971. p. 128-129

- ↑ Baxter, 1971. p. 129

- ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 42

- ↑ Sennwald, 1935. p. 85: Sternberg’s film “makes a cruel and mocking assault upon the romantic sex motif which Hollywood has been gravely celebrating all these years.”

Lopate, 2006, p. 85 - ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 41

Silver, 2010. “Dietrich steadfastly maintained it was her favorite of the films they made together...” - ↑ Sennwald, 1935. p. 86

- ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 41

Sennwald, 1935. p. 84 - ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 42

- ↑ Sennwald, 1935. p. 85

- ↑ Silver, 2010: The film is “something of a translation of the Sternberg/Dietrich relationship” and “many observers have commented on the obvious physical similarity between Sternberg and his two male protagonists.”

Sarris, 1966. p. 40 “[N]ever before has Sternberg seemed as visible in the [character of Don Pasqual], the morose figure of failure and folly.” - ↑ Silver, 2010: "If Sternberg is any closer to understanding Dietrich [in The Devil is a Woman], he is unwilling to solve the puzzle for the audience."

- ↑ Sennwald, 1935. p. 86

Sarris, 1966. p. 41 “...Atwill (Don Pasqual) and Romero (Antonio) are far from being inadequate for Sternberg’s ironies. They play fools, but not foolishly. - ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 41

- ↑ Silver, 2010

- ↑ Sennwald, 1935. p. 85

- ↑ Sarris, 1966. P. 42

- ↑ Sarris, 1966. p. 42

- ↑ Sarris, 1966. P. 42

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-18.

Sources

- Malcolm, Derek. 2000. Josef von Sternberg: The Scarlet Empress in The Guardian, 25 May 2000. Retrieved April 14, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2000/may/25/artsfeatures

- Sennwald, André. 1935. The Devil is A Woman in The New York Times, May 4, 1935. Reprinted in American Movie Critics: An Anthology From The Silents Until Now. p. 85-86. Ed. Phillip Lopate. The Library of America. New York, New York. ISBN 1-931082-92-8

- Sarris, Andrew. 1966. The Films of Josef von Sternberg. Museum of Modern Art/Doubleday. New York, New York.

- Stafford, Jeff. 2018. The Devil is A Woman in in Turner Movie Classics film review, May 17, 2017. Retrieved on April 14, 2017. http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/410471%7C87829/The-Devil-Is-a-Woman.html

- The Film Sufi: The Devil is a Woman by Josef von Sternberg (1935) in The Film Sufi, 22 July, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2018.http://www.filmsufi.com/2015/07/the-devil-is-woman-josef-von-sternberg.html