Thaat

| Hindustani classical music |

|---|

| Concepts |

| Genres |

| Thaats |

A thaat (IAST: thāṭ) is a mode in North Indian or Hindustani music.[1] Thaats always have seven different pitches (called swara) and are a basis for the organisation and classification of ragas in classical music.

The term thaat is also used to refer to the frets of stringed instruments like the sitar and the veena.[2] It is also used to denote the posture adopted by a Kathak dancer at the beginning of his or her performance.[3]

History

The modern thaat system was created by Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936), an influential musicologist in the field of classical music in the early decades of the twentieth century.[4][5] Bhatkhande modelled his system after the Carnatic melakarta classification, devised around 1640 by the musicologist Venkatamakhin. Bhatkhande visited many of the gharanas (schools) of classical music, conducting a detailed analysis of ragas. His research led him to a system of thirty-two thaats, each named after a prominent raga associated with it. Out of those thirty-two thaats, more than a dozen thaats were popular during his time; however, he chose to highlight only ten such thaats.

According to Bhatkhande, each one of the several traditional ragas is based on, or is a variation of, ten basic thaats, or musical scales or frameworks. The ten thaats are Bilawal, Kalyan, Khamaj, Bhairav, Poorvi, Marwa, Kafi, Asavari, Bhairavi and Todi; if one were to pick a raga at random, in theory it should be possible to classify it into one of these thaats. For instance, the ragas Shree and Puriya Dhanashree are based on the Poorvi thaats, Malkauns on the Bhairavi thaat, and Darbari Kanada on the Asavari thaat. Bhatkande's thaats-raga theory is not very accurate and there are quite a few ragas that don't fit into any thaat, but it is nevertheless an important classification device with which to order, and make sense of, a bewildering array of ragas. It is also a useful tool in the dissemination of the music to students.

System

In Indian musical system, swara is a Sanskrit word that means a tone of music. The seven basic swaras of the scale are named shadja, rishabh, gandhar, madhyam, pancham, dhaivat and nishad, and are abbreviated to Sa, Ri (Carnatic) or Re (Hindustani), Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, and Ni and written S, R, G, M, P, D, N. Collectively these notes are known as the sargam (the word is an acronym of the consonants of the first four swaras). Sargam is the Indian equivalent to solfege, a technique for the teaching of sight-singing. The tone Sa is not associated with any particular pitch. As in Western moveable solfège, Sa refers to the tonic of a piece or scale rather than to any particular pitch.

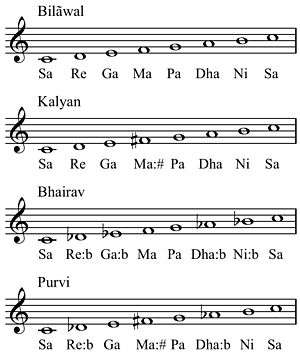

In Bhatkhande's system, the basic mode of reference is that which is equivalent to the Western Ionian mode or major scale (called Bilawal thaat in Hindustani music, Dheerasankarabharanam in Carnatic). The flattening or sharpening of pitches always occurs with reference to the interval pattern in Bilawal thaat. Each thaat contains a different combination of altered (vikrt) and natural (shuddha) notes with respect to the Bilawal thaat. In any seven-tone mode (starting with S), R, G, D, and N can be natural (shuddha, lit. "pure") or flat (komal, lit. "soft") but never sharp, whereas the M can be natural or sharp (tivra, lit. "fast") but never flat, making twelve notes as in the Western chromatic scale. The sharp or flat tones are called vikrt swara (vikrt, lit. "altered"). Selecting seven tones in ascending order, where S and P are always natural whereas five other tones (R, G, M, D, N) can assume only one of its two possible forms, results in 32 possible modes which are known as thaats. Out of these thirty-two possibilities, Bhatkhande chose to highlight only ten thaats prominent in his days.

In effect only heptatonic diatonic scales are called thaats.[6] Bhatkhande applied the term thaats only to scales that fulfil the following rules:

- A thaat must have seven tones out of the twelve tones [seven natural, four flat (Re, Ga, Dha, Ni), one sharp (Ma)]

- The tones must be in ascending sequence: Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni

- Whether natural or altered — both versions of a single tone are not allowed

- A thaat, unlike a raga, does not have separate ascending and descending lines

- A thaat has no emotional quality (which ragas, by definition, do have)

- Thaats are not sung but the ragas produced from the thaats are sung

One can arbitrarily designate any pitch as Sa (the tonic) and build the series from there. While all thaats contain seven notes, many ragas (of the audav and shadav type) contain fewer than seven and some use more. A raga need not to use every tone in a given thaat; the assignment is made according to whatever notes the raga does contain (but see note 5). The relatively small number of thaats reflects Bhatkhande's compromise between accuracy and efficiency: the degree of fit between a raga and its thaat is balanced with the desire to keep the number of basic thaats small. Ambiguities inevitably arise. For example, Raga Hindol, assigned to Kalyan thaat, uses the notes S G M D N, which are also found in Marwa thaat. Jaijaiwanti contains both shuddha Ni and komal Ni (and sometimes both versions of Ga as well), which by definition corresponds to no thaat. Bhatkande resolved such cases "by an ad hoc consideration, appealing to musical performance practice" (see Ramesh Gangolli's article, cited in note 4 above).[7]

Basic thaats

Bhatkhande named his thaats after the prominent ragas associated with those thaats. Many thaats correspond to one or other of the European church modes. The thaats are listed here according to their pitches. Lower-frequency pitches are represented with lowercase letters and higher-frequency pitches with uppercase letters.

| Thaat | Eponymous raga[8] | Notes[8] | Western | Carnatic mela[8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilaval | Bilaval | S R G M P D N Ś | Ionian | 29th, Dheerashankarabharanam |

| Kafi | Kafi | S R g M P D n Ś | Dorian | 22nd, Kharaharapriya |

| Bhairavi | Bhairavi | S r g M P d n Ś | Phrygian | 8th, Hanumatodi |

| Kalyan | Yaman (earlier known as Kalyan) | S R G m P D N Ś | Lydian | 65th, (Mecha) Kalyani |

| Khamaj | Khamaj | S R G M P D n Ś | Mixolydian | 28th, Harikambhoji |

| Asavari | Asavari | S R g M P d n Ś | Aeolian | 20th, Natabhairavi |

| Bhairav | Bhairav | S r G M P d N Ś | Double Harmonic | 15th, Mayamalavagowla |

| Marva | Marva | S r G m P D N Ś | - | 53rd, Gamanashrama |

| Poorvi | Poorvi | S r G m P d N Ś | - | 51st, Kamavardhani |

| Todi | Miyan ki Todi | S r g m P d N Ś | - | 45th, Shubhapantuvarali |

Time of performance

Ragas are normally ascribed to certain periods of the day and night (See Samay). Narada's Sangita-Makaranda, written sometime between 7th and 11th century, gives warnings to musicians against playing ragas at the incorrect time of day. Traditionally, disastrous consequences are to be expected.[9] Bhatkhande claimed that the correct time to play a raga had a relation to its thaat (and to its vadi).

Notes

- ↑ Benward and Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.39. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ↑ "Thāṭ (Instrumental)". Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195650983.001.0001/acref-9780195650983-e-4974. Retrieved 5 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Thāṭ (Kathak)". Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195650983.001.0001/acref-9780195650983-e-4976. Retrieved 5 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1909–1932). Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati. Sangeet Karyalaya (1990 reprint). ISBN 81-85057-35-4. This is the four-volume work in which Bhatkhande, after thorough analysis, makes the case for the ten thaats. Originally written in Marathi, it has been widely translated.

- ↑ Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1974). A Short Historical Survey of the Music of Upper India. Indian Musicological Society.

- ↑ Jairazbhoy 1995.

- ↑ Ramesh Gangolli (1992-12-23). "Chatura Pandit : V.N.Bhatkhande". Retrieved 2007-04-11.

- 1 2 3 GMO.

- ↑ Kaufmann 1968.

References

- Jairazbhoy, N.A. (1995). The Rags of North Indian Music: Their Structure and Evolution. Bombay: Popular Prakashan.

- Kaufmann, Walter (1968). The Ragas of North India. Calcutta, New Delhi, Bombay: Oxford and IBH Publishing Company.

- "Thāṭ (of Rāgas)". Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195650983.001.0001/acref-9780195650983-e-4976. Retrieved 5 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)). </ref>