Texan Santa Fe Expedition

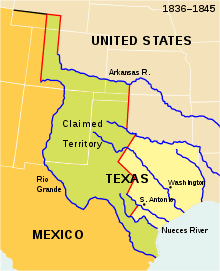

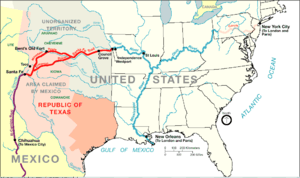

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition was a commercial and military expedition to secure the Republic of Texas's claims to parts of Northern New Mexico for Texas in 1841.[2][3] The expedition was unofficially initiated by the then President of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, in an attempt to gain control over the lucrative Santa Fe Trail and further develop the trade links between Texas and New Mexico. The initiative was a major component of Lamar's ambitious plan to turn the fledgling republic into a continental power, which the President believed had to be achieved as quickly as possible to stave off the growing movement demanding the annexation of Texas to the United States. Lamar's administration had already started courting the New Mexicans, sending out a commissioner in 1840, and many Texans thought that they might be favorable to the idea of joining the Republic of Texas.

Journey

The expedition set out from Kenney's Fort near Austin on June 19, 1841. The expedition included 21 ox-drawn wagons carrying merchandise estimated to be worth about $200,000. Among the men were merchants that were promised transportation and protection of their goods during the expedition, as well as commissioners William G. Cooke, Richard F. Brenham, José Antonio Navarro, and George Van Ness. Although officially a trading expedition, the Texas merchants and businessmen were accompanied by a military escort of some 320 men. The military escort was led by Hugh McCleod and included a company of artillery.

The journey to New Mexico during the summer was blighted by poor preparation and organization, sporadic Indian attacks, and a lack of supplies and fresh water. After losing their Mexican guide, the group struggled to find its way, with no one knowing how far away Santa Fe actually was. McCleod was eventually forced to split his force and sent out an advance guard to find a route.

The expedition finally arrived in New Mexico in mid-September 1841. Several of their scouts were captured, including Capt. William G. Lewis. Having expected to be welcomed on their arrival, the expedition was surprised to be met by a detachment from the Mexican Army of about 1500 men sent out by the governor of New Mexico, Manuel Armijo. One of Armijo's relatives who spoke English, probably Manuel Chaves or Mariano Chaves, parleyed with the Texans, with Captain Lewis supporting his statements. Both said that Armijo would give the Texans safe conduct and an escort to the border, and Lewis swore to it "on his Masonic faith".[4] After the Texans' arduous journey, they were in no state to fight a force that outnumbered them so heavily, so they surrendered. The New Mexicans gave them some supplies.

However, the following morning, Armijo arrived with his army, had the Texans bound and treated harshly, and demanded the Texans be killed, putting the matter up to a vote of his officers. That night, the prisoners listened to the council debating the idea. By one vote, the council decided to spare the Texans. The latter were forced to march the 2,000 miles from Santa Fe to Mexico City. Over the winter of 1841-42, they were held as prisoners at the Perote Prison in the state of Veracruz, until United States diplomatic efforts secured their release.[5]

After the surviving Texans were released on June 13, 1842, one of the prisoners, Robert D. Phillips, wrote to his father that: "Many of the men are waiting only for the party of a man named Cook to arrive so they may continue on to Vera Cruz and then to New Orleans.[6] The men found their way to New Orleans on board various ships, among them the Henry Clay, which, according to the ship's manifest, arrived in New Orleans on September 5, 1842, carrying 47 "Volunteers of the Texan Army Santa Fe Prisoners."

Some members of the Santa Fe Expedition

Source: Ship's Manifest fe Henry Clay, September 5, 1842:

- B. M. Bonner age 30,

- F. M. Daupthan or Daupthian age 25,

- S. Hubbard age 26,

- I or J. M. Gray age 22,

- P. Shultz age 24,

- N. Lee age 26,

- D. F. Shaw age 31,

- Q. H. Lee age 26,

- P. Yarborough age 25,

- J. L or G. Hass age 28,

- J. M. Fraywich or Feagwich age 34,

- F. H. Berne age 31,

- G. M. Carter age 29,

- J. Richardson age 22,

- H. Cabamo or simply “Alabama” age 25,

- G. N. Burk or Bund age 23,

- G. Price age 22,

- J. C. Leriot age 26,

- J. Basset or Barret age 27,

- S. T. Porter age 26,

- J. Cummings age 25,

- H. Chustrvelle or Cheesw?elle age 24,

- N. F. Mars age 25,

- D. Rookes age 27,

- C. Ray age 22,

- J. B. Cunsay or Ceansay age 29,

- J. S. Weiss age 31,

- J. Broady age 27,

- D. L. Cane age 31,

- J. Phlelps age 24,

- B. B. Bager or Bayer age 23,

- F. Eager age 22,

- J. Gonison ? age 26,

- Ths Bens age 26,

- J. Shelby age 25,

- M Able age 24,

- M. Thompson age 23,

- B. Kenedy age 28,

- J. Adair age 27,

- [No initial] Peterson age 27,

- [No initial] McPherson age 28,

- [No initial] Cass age 29,

- [No initial] Stanley age 24,

- John Rhan age 26,

- A. Mells age 25,

- C. Wolf age 25,

Source Swore Statement Bexar County District Court Sept 23, 1874 (John) Christopher Trautz age 32, Capt J. S. Sutton's Company A Regulars

Aftermath

Lewis was widely considered a traitor, but the options facing the Texans were stark, and standing and fighting would almost certainly have led to their annihilation. Furthermore, there is no information on whether Lewis or Chaves knew Armijo's real intentions. For the rest of his life, Chaves vehemently insisted that he had personally acted in good faith in dealing with the Texans.

Already under serious criticism for his mishandling of the Texan economy, Lamar was widely held responsible for the disaster and the expedition further tarnished his presidency. More importantly, the episode offered clear and convincing proof that Texas did not have the resources to maintain even a tenuous control over its claimed western territories. In a state where the overwhelming majority of inhabitants were born in the United States, unenthusiastic at best with respect to Lamar's ambitious expansionist agenda and skeptical of the very existence of a Texan national identity distinct from the U.S., such a fiasco was enough to convince many citizens to abandon whatever aspirations they had to maintain Texan independence, as they became convinced that a fledgling Republic effectively hemmed in at the Nueces River and constantly threatened with Mexican invasion could not realistically hope to be a viable country on its own. Whereas Lamar had openly boasted of plans to turn Texas into one of the continent's great powers, following the expedition Texans turned to Lamar's predecessor, the Texas Revolution war hero Sam Houston who was the leading political figure advocating annexation to the United States. In 1845, Texas was admitted to the Union.

The annexation changed the ongoing border dispute from being a quarrel between Mexico and Texas to one involving Mexico and the United States. This (combined with controversy over Mexico's treatment of Texan prisoners) helped to increase tensions between the United States and Mexico, leading up to the Mexican–American War.[7]After Armijo surrendered Santa Fe to the U.S. Army without firing a shot, Chaves formally switched allegiance to the U.S.

The war ended in victory for the United States and gave the U.S. undisputed control of all of the lands that at this point were still claimed by the State of Texas. However, Texas faced stiff opposition from within the U.S. in its bid to actually administer these lands. This resistance came largely from other Southern states, which wanted Texas' western territorial claim carved into new slave states that would maintain the balance of power in the United States Senate.

As part of the wider Compromise of 1850 between slave states and free states, the Texan state government agreed to relinquish its northwestern-most territorial claims, including the Santa Fe region that had been the focus of Lamar's expedition. In return, the federal government agreed to assume responsibility for Texan state debts. Texas was left in control of its present boundaries, which was still an area around twice the size of the territory it had ever effectively controlled as a Republic. Most of the remaining lands were organized into the New Mexico Territory while the northernmost strip remained unorganized. Armijo, who returned to New Mexico after the war, died there in 1853.

The final disposition of these regions was not settled prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, during which the Confederacy attempted to establish its own control of the region based in part on the old Texan claims. The conflict placed Chaves and the Texans on opposing sides once more, as Chaves remained loyal to the Union. Texan troops fighting under the Confederate banner would play a major role in the Confederates' unsuccessful attempt to control present-day New Mexico, while Chaves himself played a key role in the decisive Battle of Glorieta Pass.

In popular culture

A Texas Ranger is mentioned as being a "Santa Fe expeditioner" in The Lone Ranch: A Tale of the Staked Plain (1860) by Capt. Thomas Mayne Reid, having "spent over twelve months in Mexican prisons." The expedition also forms the backdrop to Clarence E. Mulford's 1922 novel "Bring Me His Ears" and to Larry McMurtry’s 1995 novel Dead Man's Walk; also the 1996 TV miniseries - which is part of the Lonesome Dove series.

References

- ↑ "Sante Fe National Historic Trail Map" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ↑ "Santa Fe Expedition". Lone Star Junction. 1998. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ Kendall, George Wilkins (1846). Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition: Comprising a Tour Through Texas and Capture of the Texans. London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ Simmons, Marc (1973). The Little Lion of the Southwest: a life of Manuel Antonio Chaves. Chicago: The Swallow Press. ISBN 978-0-8040-0633-0.

- ↑ Seymour V. Connor, "PEROTE PRISON," Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jjp02), accessed February 22, 2015. Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Phillips, Robert D. (1842–1844). Phillips Family Texan Santa Fe Expedition Letters and Documents. University of Texas Arlington Library: Unpublished.

- ↑ Texan Santa Fe Expedition at Lone Star Junction website

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Narrative of the Texan Santa Fé Expedition |

- Texas and part of Mexico & the United States : showing the route of the first Santa Fé expedition / drawn & engd. by W. Kemble., published 1850, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Texan Santa Fe Expedition

- Online Handbook of Texas

- Thomas Falconer's account from the Sons of Dewitt Colony Texas, accessed June 30, 2006

- Chapters 13–16 of George Kendall's Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition from the Sons of Dewitt Colony Texas, accessed June 30, 2006

- Phillips Texan Santa Fe Expedition Letters and Documents