Taxi dancer

A taxi dancer is a paid dance partner in a partner dance. Taxi dancers are hired to dance with their customers on a dance-by-dance basis. When taxi dancing first appeared in taxi-dance halls during the early 20th century in the United States, male patrons would typically buy dance tickets for a small sum each.[1][2][3] When a patron presented a ticket to a chosen taxi dancer, she would dance with him for the length of a single song. The taxi dancers would earn a commission on every dance ticket earned. Though taxi dancing has for the most part disappeared in the United States, it is still practiced in some other countries.

Etymology

The term "taxi dancer" comes from the fact that, as with a taxi-cab driver, the dancer's pay is proportional to the time he or she spends dancing with the customer. Patrons in a taxi-dance hall typically purchased dance tickets for ten cents each, which gave rise to the term "dime-a-dance girl". Other names for a taxi dancer are "dance hostess", "taxi" (in Argentina), and "nickel hopper" because out of that dime they typically earned five cents.

History

Taxi dancing traces its origins to the Barbary Coast district of San Francisco which evolved from the California Gold Rush of 1849. In its heyday the Barbary Coast was an economically thriving place of mostly men that was frequented by gold prospectors and sailors from all over the world.[4] That district created a unique form of dance hall called the Barbary Coast dance hall, also known as the Forty-Nine['49] dance hall. Within a Barbary Coast dance hall female employees danced with male patrons, and earned their living from commissions paid for by the drinks they could encourage their male dance partners to buy.[5]

Still later after the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and during early days of jazz music, a new entertainment district developed in San Francisco and was nicknamed Terrific Street.[6][7][8] And within that district an innovative dance hall, The So Different Club, implemented a system where customers could buy a token which entitled them to one dance with a female employee.[9][10] Since dancing had become a popular pastime, many of The So Different Club's patrons would go there to see and learn the latest new dances.[11]

However in 1913 San Francisco enacted new laws that would forbid dancing in any cafe or saloon where alcohol was served.[12] The closure of the dance halls on Terrific Street fostered a new kind of pay-to-dance scheme, called a closed dance hall, which did not serve alcohol.[13] That name was derived from the fact that female customers were not allowed — the only women permitted in these halls were the dancing female employees.[14] The closed dance hall introduced the ticket-a-dance system which became the centerpiece of the taxi-dance hall business model.[15] A taxi dancer would earn her income by the number of tickets she could collect in exchange for dances.

Taxi dancing then spread to Chicago where dance academies, which were struggling to survive, began to adopt the ticket-a-dance system for their students.[16] The first instance of the ticket-a-dance system in Chicago occurred at Mader-Johnson Dance Studios. The dance studio's owner, Godfrey Johnson, describes his innovation:

I was in New York during the summer of 1919, and while there visited a new studio opened by Mr. W___ W___ of San Francisco, where he had introduced a ten-cent-ticket-a-dance plan. When I got home I kept thinking of that plan as a way to get my advanced students to come back more often and to have experience dancing with different instructors. So I decided to put a ten-cent-a-lesson system in the big hall on the third floor of my building... But I soon noticed that it wasn't my former pupils who were coming up to dance, but a rough hoodlum element from Clark Street... Things went from bad to worse; I did the best I could to keep the hoodlums in check.[17]

This system was so popular at dance academies, that taxi dancing quickly spread to an increasing number of non-instructional taxi-dance halls.

Taxi dancers typically received half of the ticket price as salary and the other half paid for the orchestra, dance hall, and operating expenses.[18] Although they only worked a few hours a night, they frequently made two to three times the salary of a woman working in a factory or a store.[19] At that time, the taxi-dance hall surpassed the public ballroom in becoming the most popular place for urban dancing.[20]

Taxi-dance halls flourished in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s, as scores of taxi-dance halls opened in Chicago, New York, and other major cities. In 1931 there were over 100 taxi-dance halls in New York City, and between 35,000 and 50,000 men would go to these halls every week.[21][22]

However by the mid 1920s, the taxi-dance halls were coming under attack by reform movements that insisted on licensing and police supervision, and they succeeded in closing down some taxi-dance halls for lewd behavior.[23] And in San Francisco where it all started, the police commission ruled against the employment of women as taxi dancers in 1921, and taxi dancing in San Francisco would forever become illegal.[24] After World War II the popularity of taxi dancing in the United States began to diminish, and most of its taxi-dance halls disappeared by the 1960s.[25]

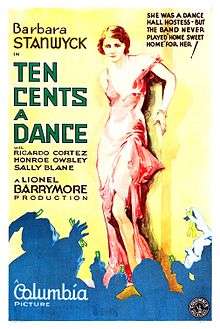

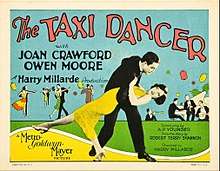

Paul G. Cressey's book, entitled The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life, gives a history of taxi dance halls, with interviews with taxi dancers and patrons. Various films and novels chronicled the lives of taxi dancers. For example, in 1927 Joan Crawford starred in the film The Taxi Dancer, and actor Ed Wynn starred in the Ziegfeld Broadway musical Simple Simon, which popularized the song "Ten Cents a Dance", which in turn inspired the 1931 film Ten Cents a Dance, starring Barbara Stanwyck.

Taxi dancers today

Taxi dancers may dance among paying customers to raise the standard or dance among the beginners to encourage them to continue learning. In the latter situation, taxi dancers often provide their services, without pay, with the general goal of building the dance community.

In social settings and social forms of dance, a partner wanting constructive feedback from a taxi dancer must explicitly request it. As the taxi dancer's role is primarily social, she is unlikely to criticize her partner directly. Due to the increased profile of partner dances during the 2000s, taxi dancing has become more common in settings where partners are in short supply, involving male and female dancers. For example, male dancers are often employed on cruise ships to dance with single female passengers. This is usually called Dance Host. Taxi dancers (male and female) are also available for hire in Vienna, Austria, where dozens of formal balls are held each year.

Volunteer taxi dancers (experienced male and female dancers) are used in dance styles such as Ceroc to help beginners.

In the United States

Paying to dance with a female employee is available in some nightclubs of the United States, including many in Los Angeles. These clubs no longer use the ticket-a-dance system, but have time-clocks and punch-cards that allow the patron to pay for the dancer's time by the hour. Some of these modern dance clubs operate in buildings where taxi dancing was done in the early 20th century. No longer called taxi-dance halls, these latter-day establishments are now called hostess clubs.[26]

For official purposes, in the United States their occupation was sometimes referred to as a 'dancer', when they worked in taxi-dance halls that had all the necessary business permits. But there were some professional secretaries who were moonlighting and legally worked part-time as a dancer.

In Argentina

The growth of tango tourism in Buenos Aires, Argentina, has led to an increase in formal and informal taxi dancing services in the milongas, or dance halls. While some operators are trying to sell holiday romance, reputable tango taxi agencies offer genuine services to tourists who find it hard to cope with the cabeceo—eye contact and nodding—method of finding a dance partner.

See also

References

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 3, 11, 17.

- ↑ Burgess, Ernest (1969). "Introduction". The Taxi-Dance Hall:A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life. Montclair,NJ: Paterson Smith Publishing. pp. xxviii. ISBN 0875850766.

- ↑ Freeland (2009), p. 192.

- ↑ Asbury (1933), p. 3.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 179.

- ↑ Knowles (1954), p. 64.

- ↑ Asbury (1933), p. 99.

- ↑ Stoddard (1982), p. 10.

- ↑ Stoddard (1982), p. 13.

- ↑ Richards, Rand (2002). Historic Walks in San Francisco. San Francisco: Heritage House Publishers. p. 183. ISBN 1879367033.

- ↑ Asbury (1933), p. 293.

- ↑ Asbury (1933), p. 303.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 181.

- ↑ Report of Public Dance Hall Committee of San Francisco of California Civic League of Women Voters, p.14

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 181.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 183.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 184.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 3.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 12.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. xxxiii.

- ↑ Ronald VanderKooi, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, March 1969.

- ↑ Freeland (2009), p. 190.

- ↑ Freeland (2009), p. 194.

- ↑ Cressey (1932), p. 182.

- ↑ Clyde Vedder: Decline of the Taxi-Dance Hall, Sociology and Social Research, 1954.

- ↑ Evan Wright, "Dance With A Stranger", LA Weekly, January 20, 1999

Strictly tango for the dance tourists, by Uki Goni, The Observer, London, 18 November 2007

Sources

- Asbury, Herbert (1933). The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 9781560254089.

- Cressey, Paul (1932). The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226120515.

- Stoddard, Tom (1982). Jazz On The Barbary Coast. Heyday Books. ISBN 189077104X.

- Montanarelli, Lisa; Harrison, Ann (2005). Strange But True San Francisco: Tales of the City by the Bay. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 076273681X.

- Knowles, Mark (1954). The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances. McFarland & Company.

- Freeland, David (2009). Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville: Excavating Manhattan's Lost Places of Leisure. NYU Press. ISBN 0814727638.