Tajemnica Statuetki

| Tajemnica Statuetki | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Metropolis Software House |

| Publisher(s) | Metropolis Software House |

| Platform(s) | DOS |

| Release | February 12, 1993 |

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Tajemnica Statuetki is a 1993 point-and-click adventure video game developed and published by Metropolis Software House for DOS-based computers. While never released in English, it is known as The Mystery of the Statuette in the Anglosphere.[1] The game, made for IBM PCs,[2] was conceived by a Polish team led by Adrian Chmielarz, who used photographs from a French holiday to serve as static screens within the game. As an adventure game, it has the distinction of being Poland's first title in the genre. Its plot revolves around fictional Interpol agent John Pollack trying to solve a mystery associated with the theft of various ancient artifacts across the world.

While piracy was rampant in Poland at the time, the game managed to sell between four and six thousand copies upon release, and became highly popular in the country. Tajemnica Statuetki was praised for its plot and for being a cultural milestone which helped advance and legitimise the Polish video gaming industry, despite some minor criticism for its game mechanics and audiovisual design.

Gameplay

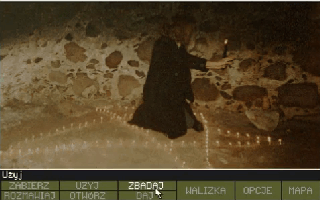

Shown from a first person perspective where players watch the action through the eyes of the protagonist,[3] the classic point-and-click adventure game consists of a series of photographic screens. The main medium of information is not graphics but text.[2] The game is divided into three chapters - each played in a different location.[4] Players solve puzzles and interact with characters to progress the story.[5] The menu is located at the bottom of the screen and offers six different actions, as well as equipment, and a map. The player uses the action commands located in the lower left hand corner of the screen, similar to LucasArts adventures.[4] Clicking a command button followed by either an inventory item or a part of the room screen, causes the player to complete an action.[4] Often, progression throughout the game required the player to locate objects the size of a single pixel on their monitor, known as pixel-hunting.[3] The game's puzzles call on the player's knowledge of various fields, such as the makeup of cocktails, when they are tasked with ordering a drink in the correct composition and proportions for a local tourist.[3]

Plot

When religious artifacts, often with insignificant market value, start to disappear across the globe, Interpol start to discern that this is not the doings of a dishonest collector. Clues cause suspicion for the global theft to be cast onto commando and former CIA agent Joachim Wadner, who comes across as extremely unhelpful and devilishly intelligent. To bring down this criminal, Interpol choose their best trainee, protagonist and playable character John Pollack, for the job. His reputation around his department saw the emergence of the saying "Pollack knows how". Pollack, a young American of Polish descent, has a blank cheque at his disposal, is able to kill with his bare hands, and can complete a Rubik's Cube in under three minutes. He takes his gadget briefcase, gets on a submarine, and sails into the Pacific Ocean.[2]

Pollack follows Wadner's trail to an island off the coast of Chile named San Ambrosio. He completes a reconnaissance mission at a local cafe by working there for weeks to complete trained movements like placing a napkin on a counter; during this time the owner changes hands but there is no progress on the case. Pollack interrogates a bartender, who says Wadner was recently there some time ago, leaving a warm trace. Offering a variety of drinks, players can choose which beverage mix to ingest, from selections such as gin, El President, Cuba Libre, Ulysses, and the American Genuine Draft, with or without lemon. Wadner then heads to the beach and admires both the nature and three young girls tanning their bodies, all of whom disregard him.[2] At one point, the player is captured and tasked with getting out of the cell; escape required the player spitting doors, frames, door handles and wires with electricity, leading to a guard's paralysis, and to counteract throat dryness from drinking a puddle.[3] The quest continues from this point through sunny cities and tourist centers, and eventually the crime mystery takes on a satanic, occult atmosphere.

Development

Tajemnica Statuetki was conceived by Lubin-born[3] Pole Adrian Chmielarz, who moved into game development in a roundabout way. In 1985, at the age of 15 Chmielarz attended the first Polcon science fiction convention in Błażejewek, where he first discovered an affinity for computers; he soon went through a Star Wars phase that saw him interact with a computer for the first time. In 1987, Chmielarz earned financial sustainability by traveling 40 miles each day to sell bootleg VHSes copied from a friend at a makeshift bazaar in Wroclaw – which according to communist Polish law was legal and deemed publishing if the seller had a permit, due to the philosophical concept of "owning the rights" being non-existent.[6] The marketplace where such goods were sold was known as the Wrocław commodity exchange (Wrocławskiej giełdy), which often had access to newer titles earlier.[3] He noted that while an Englishman could buy a game the day of release, the average Pole would often have to wait up to five weeks and become impatient during that time, leading to this natural solution.[7] According to Chmielarz "many people would buy games, if only it would be possible."[7] Nevertheless, while food was rare and hard to come by, "strangely", computers and games were relatively cheap and accessible, if not through the commodity exchange then by traveling over the border to Germany.[6] By the late 1980s, he had became fascinated by computer games by reading about them in magazines, particularly Knight Lore or Bugsy games on the cover of the fourth issue of Przegląd Techniczny.[7] He began saving for a ZX Spectrum despite never having used one before. His first experience playing games would see him typing in each line of code from gaming magazines into his friend's computer, though each time he turned off the computer the games were wiped as there was no way to save them.[6] Chmielarz was pushed by a desire to buy a computer with his own money, knowing that his parents had been forced into the black market to put food on the table.[6]

By 1990, he had bought his own ZX Spectrum computer and had more freedom with his game-playing ability.[6] Beginning computer lessons in second grade high school, he began to bury into game code and explore ways to manipulate it to alter gameplay.[3] By this time his bootleg business had expanded into a brick-and-morter company which sold different types of media including movies and games, while also building computers to feed the local business industry.[6] Chmielarz had set up a distribution deal with the to-be-founders of what would become Polish distribution company CD Projekt via the commodity exchange, whereby they would drop audiotapes full of pirated games at a local train station.[6] After picking them up, to get an advantage over his competitors at the bazaar, he would add subroutines to alter gameplay such as changing the number of lives or adding invulnerability; this marks the point when he began to make and sell his own games.[6] He bought cartridges, cracked the games, and then applied his own anti-piracy protection measures to prevent other pirates from copying and selling it.[3] Chmielarz spammed the editorial offices of Polish video game magazine Komputer with the results of his experiments.[3] He sent game descriptions to the magazine Bajtek, and won a subscription as a result.[7] One of these early titles was an erotic game called Erotic Fun, a decent experiment that sold well without any long-term profit; he later deemed this a good business lesson about exploiting an opportunity in the gaming market.[3] Some of his other early games include Kosmolot podroznik (Space Shuttle) and Sekretny dziennik adriana mole (The Secret Journal of Adrian Mole), which he designed on the Timex Computer 2048.[7] His obsession led to him playing games all the time, to the point where he would turn on the monitor to dry his face after splashing it with water first thing in the morning.[7] Sometime during this era, he came to the conclusion that the time was right for him to create the first Polish adventure game.[7]

– Adrian Chmielarz on the game's production [8]

While he had a computer engineering company, the times were getting tougher and only giants with big money could survive on the market.[9] Large companies started to enter Poland and the market became crowded.[10] Chmielarz decided to leave his profitable business and study at Wrocław University of Technology. After a few years he became bored and left without finishing his degree, and he would later regret wasting his time at college. Instead, "he and a few friends hatched a plan to take photographs from his vacation to France and turn them into a video game".[6] The group realised that they could fill a gap in the untapped Polish software market, in which hundreds of thousands of people had PCs but were unable to become fully immersed in adventure games as they did not understand English.[7] Chmielarz was not worried about the Polish gaming market being a small niche, as he knew the trail had already been set by developer X-Land. Furthermore, he has assessed that while the local market was currently not active it was potentially big, noting the amount of people who attended conventions.[7]

This project would evolve into the murder mystery point-and-click adventure Tajemnica Statuetki (known in English as Mystery of the Statuette).[6] He and his high school friends, Grzegorz Miechowski and Andrzej Michalak, had previously traded computer equipment and coding together, and had been in a rock band named The Sru;[11] this endeavour saw the trio collaborate in a new context. Chmielarz took on a directing-scriptwriting role, and set the creative tone.[12][13] From the very beginning, he approached the game with a sense of verve.[14] The team spent every free moment devoted to the creation of the title.[3] Chmielarz spent a dozen or so hours each day on the programming, over many long weeks.[3] Miechowski claimed that up until March 1993, Chmielarz wrote the game seven days a week, from 10.00 am to 2.00 am.[7] To allow him to focus on making the game, Miechowski dealt with business stakeholders and marketing while Michalak applied physiognomy to the production.[13] Grzegorz Miechowski and his brother were responsible for sales and logistics; they collaborated with computer companies Optimus and JTT.[15] In addition, Miechowski and Michalak sold computers in a second company called Gambit, taking care of the cash supply to the project.[3] Marcin M. Drews, who took some of the photos for the game including in the final scene[16], is often mistaken for the game's creator.[13] The game was born in Chmielarz's head after travelling through Côte d'Azur, photographing his life, the architecture, and nature, and building a plot around what he experienced.[15] While the team was full of enthusiasm, it was not necessarily organized.[3] For instance, while the collection of photographs was extensive, in many of them he or a colleague was in the frame, which required arduous editing to cut out these unnecessary objects.[3]

Design

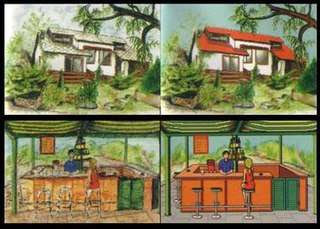

While initially supposed to have hand-drawn graphics, during development the game was altered to instead use digitised photos as static screen backgrounds.[11] Up until that point, graphic designers had spent many hours on concept art and storyboards.[17][note 1] This was atypical for the industry at the time,[18] where it was the norm to see moving protagonists and diverse locations on the screen.[19] This choice resulted in a game entirely consisting of photographical material, which all had to be properly rendered so the game could fit onto no more than two floppy disks.[18] This was necessary to minimise its cost to consumers[20] to the point where they would be willing to legally buy it.[7] The developers cut costs by opting to include photos instead of having beautiful animated video sequences.[2][7] Chmielarz recalled "we were indie before it was cool, so to speak"; as a result, the project costs for the game were kept very low.[21] Antyweb cited the game's development as one which was successful despite having a shoestring budget, noting Chmielarz "initiative" of using "home-made methods" when he didn't have access to multiple Elwro and IMB XT computers.[22] During development, he was living in Wroclaw.[2]

The game was written entirely in Assembler,[11] had a 1 megabyte source text, and contained two thousand loops, altogether around thirty thousand orders.[7] The title, typical of point-and-click adventures, required the player to control the main character with a mouse.[23] Pictures for the game were taken at the Côte d'Azur, Saint Tropez (taken over two weeks[24]), Monte Carlo, Nice and the abandoned Calvinist church and cemetery in Jędrzychowice.[11] The team went to these locations specifically for the purpose of the game, where they took as many photos as possible.[18] Meanwhile, the game's soundscape included effects such as closing the door and wiping the glass.[2] Chmielarz inserted various references to mass culture, for instance one piece of dialogue about the composition of a served drink has allusions to character of James Bond.[12] In order to make the game more appealing the developers added a skill-based section that players could skip if they wanted to.[7] A "mix of horror and thriller" according to OnlySP,[25] and mix of sensation, humor and occultism according to Chmielarz himself,[7] the final segment of Tajemnica Statuetki has a sense of fun that emulated the lighter sides of the game's production.[13] A "youthful fantasy" can be observed during a meeting with the main opponent, who is performing a magical ritual in a fiery circle made of birthday candles.[3] According to Miechowski, the game was made with the motto "Teach with fun, play with learning", and this educational slant was acknowledged by Nie tylko Wiedźmin, who claimed that the game is responsible for its players, decades later, to know how to make good cocktails as the result of an in-game puzzle.[3]

Chmielarz's design philosophy was to create a game similar to those released in the West, which provided him with an impetus.[24] Komputers Wait argues that at the time of the game's development, the Polish computer industry was lagging half a decade behind the West, and that Polish titles were generally clones of then-popular Western video games; thus Tajemnica Statuetki is comparable to late 80's adventure games.[26] Secret Service agreed, feeling that the game visually resembles point-and-click adventure Countdown (1990) and interactive fiction adventure Amazon (1984) due to their similar menu systems and use of digitized images.[2] Many critics would come to acknowledge the limitations of the game in terms of the size of the country's video gaming industry at the time.[4] One magazine would remind their readers not to make misguided comparisons between the game and the latest titles from adventure gaming giants like Sierra On-Line, LucasArts, Infogrames, or Delphine, due to the "tremendous" gaps in "experience, financial and technological resources, infrastructure, and legal protection" that would only gradually close.[27]

Release

- An addendum to a Secret Service interview with the game's creators, noting the state of piracy at the time of the game's release.[7]

Finished by February 12, 1993, with a development contributed to by around a dozen people,[7] at the end of that year[3] the game was released onto the market[28] at a price of 231,000 Polish zlotys.[3] During the game's development, the team had originally approached two publishers – Atlantis Software and Avalon Interactive (then called Virgin Interactive) – but were unsuccessful.[3] While Chmielarz was successful in getting IPS Computer Group to distribute and market the game, the company agreed to only take 100 copies rather than the 2,000 which the creators had offered; as a result, Chmielarz founded his own company to sell the rest of the stock.[3] The name of his publishing company, Metropolis Software, was chosen without special significance and simply because "it sounded nice".[3] Founded in 1992 in preparation for the release of the game the following year,[29] it became one of the first Polish video game companies after contemporaries such as Computer Adventure, Studio and X-Land.[28] Chmielarz boxed the games in packaging he had designed himself.[30] Each "aesthetic" box contained two HD floppy disks with the program, as well as extra material.[2] One of which was a copy of the fictional newspaper Dziennik Metropolis dated October 1;[2] the newspaper articles neatly presented the game's plot and contained anti-piracy safeguard information, as well as self-referential humour and an advertisement for future release Teenagent; they also contained a tiny crossword and secret codes for use in the game.[28] Running on computers with a 286 (AT) processor and requiring a VGA card, the game had to be installed on the hard drive, where the "incredibly resource-consuming product"[18] took up either around 3.2 MB,[2] less than a dozen megabytes,[3] or over 100 megabytes[18] of space and did not work properly on every computer, thought it did run successfully on high performing systems.[18] Meanwhile, the sound is supported by many different systems including Sound Blaster, Speaker and Covox.[2]

Tajemnica Statuetki became the company's premiere title.[31] The game had thoughtful promotion behind it, with Metropolis Software posting advertisements throughout industry magazines.[3] One issue of Secret Service contained a highly positive review, which they supplemented with an interview with the authors, a competition, and an advertisement.[3] The competition asked readers to send in their answers to the editorial office address by February 15, 1994, to win a Sound Blaster 2.0, 3 Genius joysticks, 5 Genius mice, and 7 books about PC computers.[32] The team placed column-sized ads in the press, with a promotional goal of making the newly founded company famous.[33] Geezmo thought the game's commercial success was largely due to a "deliberate, well-thought-out media campaign" which, in addition to the advertisement, included the sale of CDs attached to a then-popular magazine.[34] A reviewer at Gameplay, despite having a negative experience with Polish platformer Spy Master, bought this game mostly in the dark, due to the strength of its "really good press", noting that Chmielarz was adept at interesting the media with phrases such as "The first Polish adventure on PC!", "Digitized locations!", and "Realistic sounds!".[35]

Sales exceeded the estimates of IPS and the expectations of the creators themselves.[3] Chmielarz sold between 4,000 and 6,000 copies[3][note 2] by mail at a time when just a thousand or two thousand units was considered a major achievement.[36][37] Even foreign Western hits had rarely achieved that level of sales.[41] Additionally, the market was still dominated by rampant piracy.[3][12] At a time where democracy and capitalism were just being introduced to Poland[42] and in which The Software Protection Act was just being created – coming into effect in 1994 – players were not used to paying high amounts for original not-bootlegged games.[28] Polish developers had become accustomed to players pirating their games, and continued to spend months on titles despite little return.[20] According to Chmielarz, the main reason for this cultural landscape was the commodity exchange which he himself came from, and he was very critical about pirates, particular those who had tried to hack his own game. [3] One such example is CSL, who had been publicly highlighted by Gambler magazine as the "'best' Polish hacker" for cracking Tajemnica statuetki among other titles.[3] Nevertheless, despite the game being frequently pirated, a sizable number of units were sold legally.[20] Part of the reason is that CSL had only completed a partial hack, leaving some copy protection codes unbroken, a fact discovered by Chmielarz upon testing.[3] SS-NG (Secret Service - Next Generation) puts Tajemnica Statuetki's success in a piracy-prone market to it being reasonably cheap and comparable to English-language adventure games.[28] Due to the difficulty of the game, particularly a puzzle set when the protagonist is trying to escape from prison, Chmielarz received incessant calls from players who stuck unable to move on; he would have to explain the "absurd" solution over the phone.[3] Just with the profits of those initial sales, he was able to keep Metropolis Software running for two years without financial difficulty.[6] SS-NG notes that its contemporaries had begun making games for 8-bit computers, which freed up the market for Metropolis Software to pursue PC game development without competition.[28] The game's success gave the development team enough faith to put everything else aside in creating the next game.[15] They planned for this next title to follow in the footsteps of its success, being competitive not only in Poland but also in foreign countries.[43] As the game sold well, both players and reviewers eagerly awaited the next offering from this young studio.[23] The studio had set the bar very high with Tajemnica Statuetki, and so to avoid half-measures being taken, graphic designers, animators and testers were hired.[3]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

Plot and writing

The plot and writing was highly praised, and according to Video Games Around the World the game's overall positive reception from critics was mostly due to the strength of the script.[45] Gry Online praised the "greatly realized scenario" which held up the narrative,[23] while Gra.pl agreed that the best element of the title was its plot[46] and MiastoGier felt the game's engaging story outweighed its negatives.[18] GameDot thought the title "still surprises with its brilliance in the description of the surroundings and the structure of dialogues (very modeled on LucasArts productions) that bring to mind solid literary material".[12] SS-NG noted that the native language was "professionally implemented" due to there being no typos or stylistic errors, and thought the game struck a balance between humorous fun and bleak, depressing, horror-filled scenarios.[28] In addition, SS-NG thought the narrative and gameplay was well-thought out and holds up today, and added that the clever mix of humour and drama effectively broke the suspense with laugh out loud moments.[20] Secret Service argues that the game's strongest asset is the fact that it is written in Polish, including Polish language idiosyncrasies such as the declensions of nouns, as well as incorporating references to Polish jokes, stereotypes and culture.[2] The magazine believes that the authors put a lot of effort into the "extensive" text, due to it covering a number of unusual situations.[2] Benchmark argued that the "professional, tense thriller" is highly original, and it owes much of its success to the period it was released in, when technological imperfections were made up by strong concepts.[47] According to Orange, players appreciated the intriguing scenario and attention to detail, believing that the game would be able to draw new fans by 2014.[24] Polygamia thought the title was appeciated by players due to its engaging scenario, high-class criminal intrigue and thoughtful production.[9] According to Dawno temu w grach, while the game did not delight, its strength was in the execution of its well-constructed and well-written scenario, which like the best detective stories held the player in suspense until the very end.[48] Bastion Magazynów noted that the game's only draw, despite it being the only adventure game in Polish, was its well-constructed plot.[49] According to Geezmo, the "well-thought-out and moderately addictive storyline" was considered untypical at the time, and came across as both a curiosity and a novelty that invited the player to explore it.[50] Neskazmlekiem felt the overly convoluted description of getting out of the cell, including the passage "spit so long until it dries in your throat", justified the description of Chimielarz as "the greatest Polish sadist in the gaming market".[51] While noting its lack of a complicated plot and well-constructed characters, Polskie Gry Wideo wrote that the game offers hours of entertainment.[4] Valhalla thought that the plot of 2002's photographic adventure game A Quiet Weekend in Capri sounded "even worse" than that of Tajemnica Statuetki.[52] While noting that the interesting occult-inspired plot was pretty well received, even outside of Poland, the reviewer at Gameplay questioned the point of the titular "statuette" within the story.[53] SS-NG noted that the game has a great atmosphere.[54] Gambler magazine felt the game was a "very successful program" that was somewhat modeled after Sierra's Quest series.[55]

- MiastoGier on why the game captured the imaginations of its players[56]

Gry.impo felt the game was twisted, commenting that it burst with atmosphere and cult-oriented puzzles.[57]

Gameplay

The gameplay had a mixed reception from reviewers. Gry Online felt that the game was demanding and required players to patience and an open mind to find absurd solutions to puzzles.[19] Despite its difficulty, SS-NG urged players to stick with it, noting that even today the game will provide hours of entertainment.[20] Polygamia thought that while the game was not technically proficient, it was appreciated by players due to its engaging scenario, high-class criminal intrigue and careful performance.[33] SS-NG noted that in a pre-walkthrough age, the game was particularly difficult, with aspects such as copy protection revealed in the middle of the game, playing in a games room, and a useful item disguised as part of a building interior.[20] Secret Service described the gameplay as reminiscent of Infocom products, in particular The Hitchhikers Guide To the Galaxy, noting that players are required to be sharp and perceptive when interacting with found objects, which must often be used in ways contradictory to their purpose.[2] The site criticised the challenge in locating certain items, and learning of the existence of others.[2] Citing examples such as a coin on the beach, a hairpin on the sofa or a hook on the anchor, Secret Service noted that these items are the size of a single pizel and not visible on the screen, necessitating the player to find them by pixel hunting with their mouse, "creating unnecessary downtime".[2] Due to this inhibitive difficulty, the magazine suggests that the developers should have playtested the game with regular players before publishing.[2] Polskie Gry Wideo felt that the game's interface, which required pixel hunting, didn't confirm correct solutions to puzzles, didn't provide hints, and didn't provide a clear purpose of what to do in the world, put it at odds with other adventure games of the time, deeming it "a bit frustrating" and less enjoyable as a result.[4] Benchmark noted that looking for details and objects relevant in advancing through the plot required players to strain their eyes,[47] a sentiment echoed by Orange.[24] Nie tylko Wiedźmin noted that even by the standards of the time, the game was considered difficult.[3] Geezmo felt that the way the game is designed requires the player to smack the screen with their mouse.[50] While Secret Service thought the game was more modestly made that its Western counterparts, it concluded that it was solidly made due to not lagging or have game-breaking bugs.[2] Gry Online argued that the game was less fun and interesting than its successor Teenagent.[58] GameDot believes that the point and click nature of gameplay, informed by navigating through static illustrations of digitised photographs, would have nerved Chmielarz due to being a relic of an earlier time.[12] Polskie Gry Wideo noted the game's "undeveloped game design and numerous unintuitive solutions".[4]

Audiovisual design

Critics had a mixed response to the game's audiovisual design. Gry Online argues that when the game appeared on the market, "the mere use of digitized photographs was the pinnacle of the achievements of Polish programmers".[19] Michael Zacharzewski of Imperium Gier said that by 1999 standards, the game should be considered an embarrassment in terms of technical quality.[59] MiastoGier wrote that the game has impressive graphics despite its simple design.[18] PB.pl thinks the game looks "clumsy" today,[15] while Interaktywnie noted that the game appealed despite its "amateur character".[60] Radio Szczecin felt that by 2014 standards, the game had grown "unkempt", due to its static photos, lack of animation and music, and expository subtitles, which might "scare off the younger players"; however it noted that older players should play the title to remind them of what adventure games used to be.[61] SS-NG thought the audio-visuals of the game would have seemed lacking compared to Western games even at the time of release, particularly the sound effects and use of digitised photographs.[20] Gry Online noted that while the game was lacking graphically, the very use of digitized photograph was considered a milestone for the Polish video game industry at the time.[62] Describing the title as a "strong textbook with pretty images", Secret Service was disappointed that the game did not include music in the intro or line by line voice acting.[2] Video Games Around the World deemed the production values "Spartan", due to the use of digitised photographs, lack of animations and music, and minimal sound effects.[45] Polskie Gry Wideo wrote that the game's photo-based graphics noticeably contrasted with its western contemporaries such as Mystery House (1980), Maniac Mansion (1987), The Secret of Monkey Island (1990), and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis (1992).[4] SS-NG felt that the photographic material added an air of authenticity.[28] Bastion Magazynów noted that even at the time of its release, the game did not delight with sound or graphics.[49] Geezmo thought the lack of animation and its inaudible soundtrack came across as technical weaknesses.[50] MiastoGier.pl noted that the unprecedented use of incredibly photorealistic graphics caused players to be astonished.[18] Chmielarz himself agrees that the game "technically did not delight".[63] Secret Service would write that they wished the game's creators had made a version that would be compatible with inferior graphics cards.[2] SS-NG thought that the game "did not impress with graphics".[54]

First Polish adventure

Video Games Around the World argued that reviewers were willing to overlook the game's shortcomings for the sole reason that the game was the first Polish adventure for the PC.[45] SS-NG noted that as the game was only released in the native Polish, English-speakers are unable to fully enjoy it, and argued that despite its shortcomings it "won the hearts of Polish [and non-Polish] adventure lovers".[20] The site argued that it should be played by all who have not yet, even if they do not like adventure games, so they will have an appreciation of one of the first Polish video games.[20] Despite the magazine's reservations, Secret Service ultimately deemed Tajemnica Statuetkia good game, recommending it due to its affordability and accessibility while adding that "the patriotic duty of all players should be to buy it from the producer and finish it".[2] SS-NG deemed the game a source of national pride, commenting that "anyone who knew our beautiful Slavic language could play it".[28] To the reviewer, the game has a replayability that other adventure games don't have due to being a piece of their childhood, and they felt gratitude to the developers for the many hours they used to spend playing it.[28] Aleksy Uchański wrote in Gambler that at the time the Polish gaming industry had "2.5 good games of native production (and about ten times more rubbish)", most of which not influential in the development of the industry, deeming Metropolis and its early games the worthy exception.[64] While the game was unable to compete with Sierra or Lucasarts products, SS-NG felt that it was quite good by the standards of Poland at the time, writing that the best aspect of the title is that "above all, it was Polish".[65] Despite writing that in the modern age it is difficult to understand how such an average product could have been praised one day[66], Gameplay thought that playing the game was worth it, just to see what the "global hit of Polish production" once looked like.[35] Polskie Gry Wideo felt that arguably the most important thing about the game is that information is provided in Polish text, deeming it "revolutionary"[4] SS-NG suggested that while the game may have been "a bit forgotten" by 2004, that fact did not not detract from Tajemnica Statuetki's "contribution to the development of the entire domestic industry".[28] In 2014 Radio Szczecin commented that the game had not aged well, but that it was unforgettable due to being a full-blooded Polish production from its artists to its subtitles, with international action.[67] Radio Szczecin thought the title is unforgettable due to its cultural relevance, in the sense that a game with Polish artists and subtitles made a dent on the world stage.[61]

Legacy

Tajemnica Statuetki was followed by the critically acclaimed point-and-click adventure Teenagent, released in 1995,[6][12] which the company eagerly advertised thus: "The creators of Tajemnica Statuetki have been silent for over a year. See for yourself why".[68] InnPoland attributes this marketing campaign, which attached its predecessor's quality stamp on the title, to Teenagent becoming a "breakthrough",[69] while PB.pl thought this slogan "grabbed" the public.[15] The title was considered a significant step forward in quality than its predecessor and stood on its shoulders in terms of its international reach.[70] The first Polish game to have professional marketing behind it,[23] Polygamia explained that "none of the Polish producers has ever preceded their game with such great marketing efforts", and that this created media buzz around the title.[33] According to Eurogamer, "the studio was flush with the early successes" of these two games.[30] Among the studio's later work would be 1998 satirical adventure game The Prince and the Coward, created with the help of the fantasy writer Jacek Piekara.[71] The title would round out the trilogy of adventure games that Chmielarz started his game designer career with.[25] Chmielarz thought the title, one of his first three commercially released games, was more convincing than his first ZX Spectrum games.[1] A continuation of the Tajemnica Statuetki story, which was to appear on CD, was announced. The initial photographic material for the game was collected, but eventually work was suspended due to Metropolis Software devoting its efforts to other projects.[11][23] As of December 1994, there was still an expectation by Secret Service that Tajemnica Statuetki 2 would be released, most likely in 1995.[72] Bajty Polskie noted that even in 2015, players still anticipated a sequel to the game, with a colorfully described premise in which Pollack goes on a vacation with a friend to a Polish castle by the Masurian Lake, when an ambulance takes away his friend.[73]

A personal conflict between Chmielarz and Miechowski led to Chmielarz leaving the company around 2002 to form People Can Fly.[74] Metropolis Software would be acquired by CD Projekt in 2008 as a subsidiary[75] and become defunct the following year[76]; out of its ashes Miechowski would found 11 bit studios.[77] Metropolis owned the rights to this game, which were passed onto CD Projekt when they bought the company; they presumably still own the rights.[78] The use of holiday pictures as part of the game's visual language partially inspired People Can Fly developer Wojciech Pazdur to use photogrammetry to help build levels for the first-person shooter Painkiller.[79] The 2004 adventure game Ramon's Spell, according to SS-NG, was modeled on this game.[80] Tajemnica Statuetki saw Metropolis begin its love affair with special service agents, a trope which would reappear in many of their later games including 2007's Infernal, albeit with violence taking the place of cunning.[58] Chmielarz, the "Polish Sid Meier"[81] felt that his 2014 game The Vanishing of Ethan Carter saw him return to his adventure gaming roots of the Tajemnica Statuetki era,[82] while Gamezilla believes the latter title would not have existed without the former.[83]

Adam Juszczak's piece Polski Rynek Gier Wideo – Sytuacja Obecna Oraz Perspektywy Na Przyszłość noted the "breakthrough" nature of the game in a larger context: the Polish computer games market had been delayed due the Socialist system and the lack of wide access to computers and consoles; as a result it had only begun to develop in the 1980s with the first Polish computer magazine, Bajtek, appearing on the market in 1985 (initially as an addition to youth magazine Sztandar Młodych before becoming a standalone magazine). Around this time the first Polish games also began to emerge, placing Tajemnica Statuetki in a permanent part of the history of Polish entertainment.[84] During the 1980s, the cheap and talented workforce of the Polish People's Republic began producing video games with Warsaw company Karen, founded by enterprising emigrant Lucjan Wencel, developing many hits that were released in the United States.[85] The 1991 strategy game "Solidarność" by Przemysław Rokita, where players led a trade union to political victory, was the symbolic beginning of a new trend where interactive works applied video game conventions to local Polish culture and history[85], and through a distorting mirror portrayed the Eastern Bloc, local villages, and the mentality of citizens.[86] Developers in this age struggled with minimal profits, working after hours, harsh working conditions, older computers, and an ignorance of foreign languages and sentiments.[85] The country saw its own text based games – e.g. Mózgprocesor (1989), arcade games – e.g. Robbo (1989), football manager – Polish League (1995), Doom-clone – Cytadela (1995), and The Settlers-clone – Polanie (1995), however the adventure game genre was the "most significant species in the 90s", a genre which was finally cracked with Tajemnica Statuetki.[85] Tajemnica Statuetki was the first commercially released Polish adventure game,[18][87] one of the first Polish and Polish-language video games ever,[20] and Chmielarz's first game that he had developed from start to finish[36] – the first officially sold program that he wrote.[88] It is sometimes erroneously considered the first Polish computer game, a distinction held by Witold Podgórski's 1961 mainframe game Marienbad, inspired by a Chinese puzzle called "Nim", and released on the Odra 1003.[89] (Meanwhile, Polygamia writes that 1986's text-based Puszka Pandory is the first game written by a Pole, sold in Poland, and reviewed in Polish press).[90] Despite this, Onet wrote in 2013 about a common misconception that the game marks the point where the history of digital entertainment in Poland begins.[91]

- SS-NG reviewer Jacek Marciniak, on Tajemnica Statuetki's impact on the development of the Polish computer games market,[28]

The game had a wide impact on the domestic market.[20] InnPoland wrote that the game was one of the first Polish titles to "enjoy hit status".[69] The game became an "undoubted success",[12] and a "loud hit of the AT-era".[92] The game stood out significantly against the background of semi-similar adventure game from Mirage, LK Avalon and ASF, and it was difficult to confuse it with other titles.[3] Nie tylko Wiedźmin felt that IPS' behaviour as a publisher was a "funny...anecdote" due to the unprecedented success of the game.[3] MiastoGier thought that Metropolis Software's early work was part of the golden age of adventure games, after the age of animation spites and connected frames; the site deemed it an important piece of cultural history for adventure gamers, that shows the beginnings of Polish game development and the start of Adrian Chmielarz's career; the site therefore described the game as "legendary".[18] Onet deemed Tajemnica Statuetki the "one of the most important games in the history of virtual entertainment".[89] The game "allowed Metropolis Software to "gain recognition in the Polish PC world of adventure games admirers".[93] In addition, Onet thought the "breakthrough", "exceptional", "significant", and "excellent" game revolutionized Polish game development and "for years it marked the direction of the industry from the Vistula to the Oder".[94] While the game is virtually unheard of in the Western World,[6] it was a "great success for the fast-paced Polish audience".[15] Furthermore, SS-NG proclaimed that so much had been written about the game that certain points of analysis had become hackneyed.[28]

According to Polygon, "thanks to piracy just about every gamer of a certain age in Poland has played Mystery of the Statuette".[30] Part of the reason was due to a Metropolis Pack put together by pirates and released as shareware, which contained Tajemnica Statuetki, Teenagent, and Katharsis.[95] SS-NG argues that unprofitability of the industry due to piracy necessitated a leap of faith on Chmielarz's part.[20] Nowadays, Chmielarz is considered a "living legend" in the Polish video gaming industry,[20] and "one of the most important computer game developers" in the country.[69] Polskie Gry Wideo shrugged off the title's underwhelming aspects as the "first, clumsy steps" at the beginning of Chmielarz's influential career, ultimately calling it a "step in the right direction".[4] The pioneering history of early Polish video game development, and specifically the creation of Tajemnica Statuetki, was addressed in the Polish-language book "Not Only The Witcher, The History of Polish Computer Games".[96] In 2014, Orange listed the game as the 6th best Polish game of the 1990s.[97] Logo 24 listed the game as one of the "Top 10...most important Polish games", deeming Chmielarz "probably the most known and respected Polish game developer".[37] In 2016, the game was exhibited as part of the Digital Dreamers exhibition at the Palace of Culture and Science Sciences in Warsaw. The game was listed by Benchmark in their article Najlepsze polskie gry (The best Polish games).[47] Marcin N. Drews and Adrian Chmielarz reunited for a panel at the 2017 Pixel Connect convention, where they spoke about this game.[98] Chmielarz had previously spoken about the game in a 2013 panel with other early Polish game developers.[99] The game can be legally played at GOG.com.[35]

Notes

- ↑ While the game's photographic material had become a signature of its design, these storyboards and concept art were first brought to light during an interview with Secret Service in 1996.[17]

- ↑ Number of sales varies according to estimates: 4,000,[36][12] 5,000,[15][37][38] over 5,000,[39][40] or over 6,000 copies[30]

References

- 1 2 Chmielarz, Adrian (April 30, 2014). "Seven Deadly Sins of Adventure Games". The Astronauts. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Marczewski, Jacek (August 1993). Tajemnica statuetki. Secret Service (in Polish). Warsaw: ProScript Sp. z o. o. pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Marcin, Kosman. Nie tylko Wiedźmin. Historia polskich gier komputerowych. pp. 89–93. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Tajemnica Statuetki – recenzja". Polskie Gry Wideo (in Polish). March 25, 2016. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Tajemnica Statuetki (PC)". www.komputerswiat.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hall, Charlie (July 16, 2014). "The Astronauts: A Polish team gets small to think bigger". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Mały Gigant – Wywlad z autorami gry TAJEMN1CA STATUETKI: Adrlanem Chmlelarzem (A.Ch.) i Grzegorzem Miechowskim (Q.M.) (in Polish). Secret Service. August 1993. pp. 20–1.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (in Polish). Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 "Opowieści z krypty: Teraz Polska | Polygamia". polygamia.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Adrian Chmielarz – człowiek, który uwierzył, że ludzie potrafią latać". forsal.pl. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Czajkowski, Michał. "Tajemnica Statuetki: Ciekawostki o grze". Przygodoskop (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Gry stare ale jare #46 – Teenagent". Gamedot (in Polish). July 9, 2015. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Adrian Chmielarz – sztukmistrz z Lubina – geniusz, bufon, globalny autorytet?". Onet Gry (in Polish). October 30, 2014. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Nowy mroźny świat". pb.pl (in Polish). Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ Mateusz (May 7, 2017). "Marcin M. Drews – ustatkowany gracz?". Ustatkowany Gracz (in Polish). Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- 1 2 Gul (1996). Teenagent CD. Secret Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Onysk, Wojciech "Raaistlin" (May 16, 2013). "RetroStrefa – Tajemnica Statuetki". MiastoGier.pl. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Tajemnica Statuetki (PC) | GRYOnline.pl". GRY-Online.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Marciniak, Jacek "AloneMan" (2003). "Tajemnica Statuetki (page 15)". SS-NG (in Polish). Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Ile kosztuje stworzenie gry i dlaczego tak dużo? | Polygamia". polygamia.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Marcin M. Drews: Wspierajmy polski gamedev – AntyWeb". AntyWeb (in Polish). September 21, 2012. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiater, Paweł (October 5, 2012). "Historia polskich gier: Metropolis Software i Adrian Chmielarz". Gra.pl. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Polskie gry lat 90. – część 1 – Galerie zdjęć | Orange Polska". www.orange.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 Williams, Lachlan (January 16, 2014). ""Weird Fiction Horror" – The "Clumsy Unease" Behind The Vanishing of Ethan Carter – Exclusive Interview". OnlySP (Only Single Player). Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Cudze chwalicie, a swoje...? Lokalny patriotyzm a postrzeganie polskich gier". Gamezilla (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ Iwatani, Toru (2015). Video Games Around the World. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262527163.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Marciniak, Jacek "AloneMan" (2004). "Tajemnica Statuetki". SS-NG (in Polish). p. 50.

- ↑ "Metropolis Software – gry, minigry, opisy gier, darmowe gry, solucje do gier, poradniki do gier". gamedile.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Purchese, Robert (May 19, 2015). "The Witcher game that never was". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2015). Video Games Around the World. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262527163. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017.

- ↑ Tajemnica Statuetki competition. Secret Service. p. 51.

- 1 2 3 "Opowieści z krypty: Teraz Polska | Polygamia". polygamia.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "the astronauts – Geezmo.pl". geezmo.pl. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Mruqe (April 7, 2012). "Dyskietki na dnie szafy - wspomnienia gracza". Gameplay (in Polish). Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Przekrʹoj (in Polish). Czytelnik. 2001. p. 50. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Top 10: najważniejsze polskie gry". Logo24 (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Adrian Chmielarz – człowiek, który uwierzył, że ludzie potrafią latać". forsal.pl. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Polskie gry lat 90. – część 1 – Galerie zdjęć | Orange Polska". www.orange.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "the astronauts – Geezmo.pl". geezmo.pl. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Polskie gry lat 90. – część 1: Tajemnica Statuetki". Orange (in Polish). August 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Hall, Charlie (July 16, 2014). "The Astronauts: A Polish team gets small to think bigger". Polygon. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Agent Mlíčňák". iDNES.cz. January 24, 2000. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Tajemnica Statuetki (PC) - GRYOnline.pl". GRY-Online.pl.

- 1 2 3 Iwatani, Toru (2015). Video Games Around the World. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262527163.

- ↑ "Historia polskich gier: Metropolis Software i Adrian Chmielarz". www.gra.pl. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Kralka, Jakub (May 8, 2010). "Najlepsze polskie gry: Tajemnica Statuetki". Benchmark (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Kluska, Bartlomiej (2008). "Domu Tenu W Grach" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- 1 2 Marciniak, Jacek "AloneMan". "Przygodówki". Bastion Magazynów.

- 1 2 3 "the astronauts – Geezmo.pl". geezmo.pl. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Pixel Connect 2017, relacja z pierwszego dnia Pixel Heaven – neskazmlekiem.pl". neskazmlekiem.pl (in Polish). May 29, 2017. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Tajemnica Statuetki powraca?". Valhalla.pl (in Polish). July 4, 2006. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ gameplay.pl, Mruqe, for. "Dyskietki na dnie szafy – wspomnienia gracza". gameplay.pl. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 Marciniak, Jacek "AloneMan" (2004). "Teenagent". SS-NG (in Polish). p. 27.

- ↑ Tajemnica Statuetki (in Polish). Gambler magazine. p. 61.

- ↑ MG-Soft. "RetroStrefa – Tajemnica Statuetki – MiastoGier.pl". www.miastogier.pl. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20060616035911/http://gry.imro.pl/?exec=game,9473,3,346

- 1 2 "Infernal". Onet Gry (in Polish). January 22, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Polska, Grupa Wirtualna. "Tajemnica Statuetki – Gry.wp.pl". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Myślisz, że polskie gry to tylko Wiedźmin? To poznaj 11 Bit Studios". interaktywnie.com (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 "[21.09.2014] Tajemnica Statuetki (1993r.) – GiermaszGiermasz – Radio SzczecinRadio Szczecin". radioszczecin.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Tajemnica Statuetki". Gry Online (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Czubkowska, Sylwia (February 19, 2011). "Adrian Chmielarz – człowiek, który uwierzył, że ludzie potrafią latać". Forsal.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ Uchański, Aleksy (October 7, 2009). "Gambler 2/96 article, quoted in Opowieści z krypty: Teraz Polska". Retro-Strefa (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ Marciniak, Jacek "AloneMan" (September 2004). "Ramon's Spell". SS-NG (in Polish).

- ↑ Mruqe (April 7, 2012). "Dyskietki na dnie szafy – wspomnienia gracza". Gameplay (in Polish). Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ Kutys, Andrzej (September 9, 2014). "[21.09.2014] Tajemnica Statuetki (1993r.)". Radio Szczecin (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Gry stare ale jare #46 – Teenagent". Gamedot (in Polish). July 9, 2015. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Burtan, Grzegorz (April 4, 2016). "Wspomnień czar. Teenagent, Wacki, Książę i Tchórz – w to grano, kiedy Wiedźmin był jeszcze bohaterem opowiadań". INN Poland. (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Bądź kimkolwiek zechcesz. Najważniejsze gry przygodowe XX wieku". Gadżetomania.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Walerych, Dawid (August 25, 2014). "25 lat wolności w grach wideo". Technopolis (in Polish). Polityka. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ Ass, Pegaz (December 1994). Przecieki. Secret Service. p. 12.

- ↑ Kluska, Bartłomiej; Rozwadowski, Mariusz (August 21, 2015). Bajty Polskie (in Polish). e-bookowo. ISBN 9788392722939.

- ↑ Hall, Charlie (July 16, 2014). "The Astronauts: A Polish team gets small to think bigger". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ Staff, I. G. N. (February 18, 2008). "Metropolis Joins CD Projekt Group". IGN. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Wiedźmin. 10 faktów na 10-lecie gry". EskaROCK (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "W pogoni za „Wiedźminem". Kto powtórzy sukces CD Projektu?" (in Polish). May 24, 2017. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ Kosman, Marcin (October 24, 2012). ""Wolność smakuje słodko" – wywiad z Adrianem Chmielarzem, współzałożycielem studia The Astronauts". Gamezilla (in Polish). Komputer Świat. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Jak powstawało polskie Get Even – rozmowa z The Farm 51". Eurogamer.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ Marciniak, Jacek "AloneMan" (2004). "Ramon's Spell". SS-NG.

- ↑ "People Can Fly bez Adriana Chmielarza" (in Polish). August 13, 2012. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Adrian Chmielarz – The Vanishing of Ethan Carter". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ Olszewski, Paweł (November 11, 2014). "Dobre, bo polskie? Rodzime gry wideo podbijają świat". Gamezilla (in Polish). Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Juszczak, Adam (2016). "Polski Rynek Fier Wideo – Sytuacja Obecna Oraz Perspektywy Na PrzyszoŚĆ" (in Polish).

- 1 2 3 4 "25 lat wolności w grach wideo". Technopolis (in Polish). Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Polska, Grupa Wirtualna. "A Quiet Weekend in Capri". Gry.wp.pl. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Piekara, Jacek (1998). Co ja robie tu?. Gambler Magazine. p. 73.

- 1 2 Quark (July 15, 2013). "Dawno, dawno temu, zanim powstał "Wiedźmin"…". Onet (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ Kluska, Bartłomiej (March 5, 2010). "Opowieści z krypty: Puszka Pandory". Polygamia (in Polish). Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Słyszeliście kiedyś o "Marienbad", pierwszej polskiej grze wideo w historii? Nie? No to koniecznie musicie nadrobić zaległości!". Onet Gry (in Polish). March 18, 2013. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Reflux". PCWorld. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Książę i Tchórz – recenzja – Adventure Zone – Przygodówki od A do Z". www.adventure-zone.info (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Słyszeliście kiedyś o "Marienbad", pierwszej polskiej grze wideo w historii? Nie? No to koniecznie musicie nadrobić zaległości!". Onet (in Polish). March 18, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Rodzeri, Jakub. Polska jakosc. Gambler Magazine. p. 56.

- ↑ "Do kogo skierowana jest książka "Nie tylko Wiedźmin. Historia polskich gier komputerowych"?". Gamezilla (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Polskie gry lat 90. - część 1 (6 /10)". Orange (in Polish). August 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Górska, Neska (May 29, 2017). "Pixel Connect 2017, relacja z pierwszego dnia Pixel Heaven". Neska Z Mlekiem (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Atari. "Atari". atarionline.pl. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.