Stoke Row, Oxfordshire

| Stoke Row | |

|---|---|

St John the Evangelist parish church | |

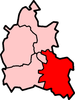

Stoke Row Stoke Row shown within Oxfordshire | |

| Area | 6.08 km2 (2.35 sq mi) |

| Population | 651 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 107/km2 (280/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SU6884 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Henley-on-Thames |

| Postcode district | RG9 |

| Dialling code | 01491 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| EU Parliament | South East England |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Stoke Row |

Stoke Row is a village and civil parish in the Chiltern Hills, about 5 miles (8 km) west of Henley-on-Thames in South Oxfordshire and about 9 miles (14 km) north of Reading. The 2011 Census recorded the parish population as 651.[1]

History

The earliest known surviving record of the toponym is from 1435. Stoke is a common place-name derived from Old English, typically meaning a secondary settlement or outlying farmstead. With the affix "row" it means a "row of houses at Stoke" .[2]

Stoke Row was a hamlet divided between the ancient parishes, and later civil parishes, of Ipsden, Newnham Murren and Mongewell. It was made a chapelry in 1849.[3] From 1932 it was divided between Ipsden and Crowmarsh, into which Newnham Murren and Mongewell were merged.[4] In 1952 Stoke Row was made a new civil parish.[5]

Stoke Row Independent Chapel

History

There is a history of Dissenters meeting in the village.[6] Dissenters had been meeting in the village since 1691, when they gathered in the drawing room of a local farmhouse. Stoke Row Independent Chapel was built in 1815. It is a simple red brick Georgian building with flint footings and a hipped roof of slate.[7] In 1884 Sunday school room was built at the back of the chapel.[8]

In the early years services were conducted by visiting ministers or licensed lay preachers, but in 1955 a wealthy local farmer, who had been a lifelong strong supporter, bequeathed a large piece of land opposite the chapel and on this houses were built. The resulting finance enabled a house to be built for the Minister and for chapel modernisation, including modern heating and an extension built in 1956[8] that includes a kitchen and toilets. A trust was also established and this still provides for the upkeep of the exterior of both buildings.

In 1978 Padre Bernard Railton Bax took over the ministry. His work was continued, after his death in 1990, by Rev John Harrington and his wife Nina. Mrs Harrington died in 1996 and Rev Harrington retired at the age of 87, after 13 years of service.

The chapel has always been independent, but it has neighbourly links with the local Church of England parish church of St John the Evangelist. There was once a move to integrate with the Congregational Church, but the plan did not materialise. The chapel has an ecumenical attitude and residential Ministers in recent years have included a Baptist and several from a United Reformed Church background.

In 2016 the chapel has a choir and the meeting room, at the rear of the chapel, is used by many groups, one on a weekly basis. The current ministers are Revd David and Revd Sonia Jackson.

In June 2015 an outdoor service was held, attended by many villagers, to celebrate the chapel's bicentenary. The congregation sat in a marquee in the chapel grounds and sang hymns with accompaniment from the Reading Central Salvation Army brass band. Rev David and Rev Sonya Jackson gave readings and led prayers, as did Rev Kevin Davies, the minister for Henley deanery. The service was followed by a village picnic. A celebration cake was cut by 95-year-old Ken Jago, the oldest member of the congregation.[9]

Ministers

- 1959–65: Pastor Ernest Dickerson

- 1967–72: Rev John Potts

- 1973–75: Rev Arthur Tilling

- 1977–90: Rev Padre Bernard Railton Bax

- 1990–2004: Rev John Harrington

- 2004–10: Rev David Holmwood

- 2010–16: Revs David and Sonia Jackson

- 2016– present: Rev Mark Taylor

Parish church

The Church of England parish church of St John the Evangelist was consecrated in 1846.[10] It was designed in 13th century style by the architect RC Hussey.[11] It is built of knapped flint with stone dressings. The church has a north tower with an octagonal belfry and short spire with wood shingle roof.[12] The ecclesiastical parish is now a member of The Langtree Team Ministry: a Church of England benefice that includes also the parishes of Checkendon, Ipsden, North Stoke, Whitchurch-on-Thames and Woodcote.[13]

Maharajah's Well

Edward Anderdon Reade, the local squire at Ipsden, had worked with the Maharajah of Benares in India in the mid-nineteenth century. He had sunk a well in 1831 to aid the community in Azimgurgh. Reade left the area in 1860.

A couple of years later the Maharajah decided on an endowment in England. Recalling Mr Reade’s generosity in 1831 and also his stories of water deprivation in his home area of Ipsden the Maharajah commissioned the well at Stoke Row and it was sunk in 1863.[11] The originally intended site for the well was Nuffield Common. All work was completed by the Wallingford firm of R. J. and H. Wilder.[14]

Amenities

The village has two 17th-century pubs: the Cherry Tree Inn[15] and the Crooked Billet.[16] The Cherry Tree Inn[17] is a Brakspear tied house.

The Crooked Billet,[18] a free house, was built in 1642 and is reputed to have once been the hideout of highwayman Dick Turpin, who was said to have been romantically attached to the landlord's daughter, Bess.[19] It was England's first gastropub and was the venue for Titanic star Kate Winslet's wedding reception. In June 1989 the British progressive rock band Marillion played its first performance with Steve Hogarth as frontman at the Crooked Billet. A documentary DVD called From Stoke Row To Ipanema – A Year In The Life was subsequently produced.[20]

In the 1851 Census the head of the household at No 1 Stoke Row was George Hope, who built "The Hope" public house.[21] This was later called "The Farmer" and today is Hope House, at the junction of Main Street with Nottwood Lane.

The parish has a Church of England primary school.[22]

Notable residents

- George Cole (1925–2015), actor, lived in Stoke Row for more than 70 years.[23]

- Nick Heyward (born 1961), singer-songwriter and guitarist, currently lives in the village.[24]

References

- ↑ "Stoke Row Parish". nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Watts 2010, Stoke Row

- ↑ Wilson & 1870–72,

- ↑ "Crowmarsh CP". Vision of Britain. University of Portsmouth.

- ↑ "Stoke Row CP". Vision of Britain. University of Portsmouth.

- ↑ "Journals of the House of Lords". 1833. p. 306.

- ↑ "Independent Chapel". Oxfordshire Historic Churches Trust. 12 September 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- 1 2 Historic England. "Stoke Row Independent Chapel (Grade II) (1271461)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Celebrating 200 years of worship". Henley Standard. Higgs Group. 27 June 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ Lewis 1848, pp. 220–224.

- 1 2 Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 789

- ↑ Historic England. "Church of St John the Evangelist (Grade II) (1369052)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Locations". The Langtree Team Ministry. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Williamson 1983

- ↑ Historic England. "Cherry Tree public house (Grade II) (1059327)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Crooked Billet public house (Grade II) (1180667)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Cherry Tree Inn

- ↑ The Crooked Billet

- ↑ "Past and Present". The Crooked Billet. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Steve Hogarth's first Marillion Gig at The Crooked Billet". Archived from the original on 5 June 2012.

- ↑ "Stoke Row Census Return 1851". Angela Spencer-Harper. February 2002.

- ↑ Stoke Row Church of England Primary School

- ↑ Ward, Victoria (31 August 2013). "Actor George Cole in dispute over local sawmill". Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ "Nick Heyward". Henley Life: 7. August 2014. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

Sources

- Lewis, Samuel, ed. (1931) [1848]. A Topographical Dictionary of England (Seventh ed.). London: Samuel Lewis. pp. 220–224.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 789. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- Spencer-Harper, Angela (1999). Dipping into the Wells: The Story of the Two Chiltern Villages of Stoke Row and Highmoor Seen Through the Lives of Their Inhabitants. Witney: Robert Boyd Publications. ISBN 1-899536-35-3.

- Watts, Victor, ed. (2010). "Stoke Row". The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 510, 577.

- Williamson, LD (1983). An Illustrated History of The Maharajah's Well. Stoke Row: The Maharajah's Well Trust.

- Wilson, John Marius (1870–72). Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales. London and Edinburgh: A Fullarton and Co.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stoke Row. |