Stadium subsidy

A stadium subsidy is a type of government subsidy given to professional sports franchises to help finance the construction or renovation of a sports venue. Stadium subsidies can come in the form of tax-free municipal bonds, cash payments, long-term tax exemptions, infrastructure improvements, and operating cost subsidies. Funding for stadium subsidies can come from all levels of government and remains controversial among legislators and citizens. There is an ongoing debate among economists and municipalities about the aggregate effects of hosting a professional athletic team. [1][2]

Background

In the United States

Eighty years ago, stadium subsidies were essentially unheard of, with funding for professional sports stadiums coming from private sources. In 1951, MLB commissioner Ford Frick decided that league teams were bringing large amounts of revenue to their host cities from which owners weren't able to profit. He announced that cities would need to start supporting their teams by building and maintaining venues through public subsidy.[3] Today, most new or renovated professional sports stadiums are financed at least partly through stadium subsidies. While Frick may have been a catalyst, this change has been primarily caused by the increase in bargaining power of professional sports teams at the expense of their host cities. As the years have passed, municipalities have come to love their local professional sports teams.

Recently there have been many studies that have suggested that there are a number of direct and indirect economic benefits associated with hosting a professional sports team, although each city experiences this to a different degree.[4][5] Even still, a survey conducted in 2017 found that "83% of economists polled believed that a subsidy's cost to the public outweighed the economic benefits".[6][7] The economics behind issuing billions of dollars to professional athletic organizations are still unclear, but cities have clearly showed that they are willing to assume the best, as recent years have seen an increase in the number of subsidies issues and the amount of money issued per subsidy.[8][9][10]

Twenty-seven of the 30 stadiums built between 1953 and 1970 received more than $450 million in total public funding for construction.[11] During this period, publicly funding a stadium grew in popularity as an effective incentive to attract professional sports teams to up and coming cities. Famous examples include the Brooklyn Dodgers leaving New York in exchange for 300 acres in Chavez Ravine and the New York Giants moving to San Francisco for what would eventually become Candlestick Park.[12] The Los Angeles Coliseum became the first fully publicly funded stadium in 2018.[13]

Over time, a market for subsidies has come into existence. Sports teams have realized their ability to relocate at lower and lower costs to their private contributors. Because local governments feel that keeping their sports teams around is critical to the success of their cities, they comply and grant teams subsidies. This creates a market for subsidies, where professional athletic organizations can shop between cities to see which municipality will provide them with the most resources. Teams in the NFL have a major incentive to keep their stadium up to date, as the NFL allows teams to bid to host the Super Bowl and takes recent and planned renovations into account.[14][15] Many NFL teams in recent years have asked for subsidies for the construction of entirely new stadiums, like the Atlanta Falcons, who were subsequently awarded the contract for Super Bowl LIII.[16]

In Europe

Public subsidies for major league sports stadiums and arenas are far less common in Europe than in the United States. The relationship between the local clubs and the cities that host them is typically much stronger than in the United States, with the team being more intrinsic to the cities' identity. Cities would be significantly more upset at the departure of their beloved local teams, and viable alternative cities already have their own clubs to whom their residents are loyal. As a result, the leagues in Europe have significantly less bargaining power. They will not threaten to relocate to another city if not provided with a subsidy, or at the very least the threat would not be credible[17]. It is also worth noting that the NFL, the league in the United States whose stadiums have the highest percentage of public financing of the four major leagues, does not have an equivalent in Europe; American football is relatively unpopular.

Types of Subsidies

There are two primary ways that a city facilitates the construction of a stadium. The first, and most commonly used method, is a direct subsidy. This involves a city promising a certain amount of revenue to go towards the construction, maintenance, and renovation of a stadium. Other times, the city will give tax breaks to teams or stadium owners in lieu of a direct cash transfer.[18] Over a period of time, a reduction in the taxes paid against the stadium generally saves the organization building the stadium around the same amount as a subsidy would be worth.

In the USA, the annual subsidies provided by the state for the construction of stadiums are in the range of billions of dollars.[19][20] A 2005 study of all sports stadiums and facilities in use by the four major leagues from 1990 to 2001 calculated a total public subsidy of approximately $17 billion, or approx. $24 billion in 2018 dollars. The average annual subsidy during that period was $1.6 billion ($2.2 billion in 2018) for all 99 facilities included in the study, with an average of $16.2 million ($22.8 million in 2018) per facility annually.[21] A 2012 Bloomberg analysis estimates that tax exemptions annually cost the U.S. Treasury $146 million.[2]

| NBA | NFL | MLB | NHL |

| Cleveland Cavaliers | Buffalo Bills | Baltimore Orioles | Boston Bruins |

| Oklahoma City Thunder | Miami Dolphins | Boston Red Sox | Buffalo Sabres |

| Golden State Warriors | New England Patriots | New York Yankees | Detroit Red Wings |

| Atlanta Hawks | New York Jets | Tampa Bay Rays | Florida Panthers |

| Indiana Pacers | Baltimore Ravens | Toronto Blue Jays | Montreal Canadiens |

| Houston Rockets | Cincinnati Bengals | Chicago White Sox | Ottawa Senators |

| Utah Jazz | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland Indians | Tampa Bay Lightning |

| New York Knicks | Pittsburgh Steelers | Detroit Tigers | Toronto Maple Leafs |

| Brooklyn Nets | Houston Texans | Kansas City Royals | Carolina Hurricanes |

| Orlando Magic | Indianapolis Colts | Minnesota Twins | Columbus Blue Jackets |

| Miami Heat | Jacksonville Jaguars | Houston Astros | New Jersey Devils |

| Boston Celtics | Tennessee Titans | Los Angeles Angels | New York Islanders |

| Denver Nuggets | Denver Broncos | Oakland Athletics | New York Rangers |

| Los Angeles Clippers | Kansas City Chiefs | Seattle Mariners | Philadelphia Flyers |

| Los Angeles Lakers | Los Angeles Chargers | Texas Rangers | Pittsburgh Penguins |

| Minnesota Timberwolves | Oakland Raiders | Atlanta Braves | Washington Capitals |

| Portland Trailblazers | Dallas Cowboys | Miami Marlins | Chicago Blackhawks |

| Washington Wizards | New York Giants | New York Mets | Colorado Avalanche |

| Dallas Mavericks | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia Phillies | Dallas Stars |

| San Antonio Spurs | Washington Redskins | Washington Nationals | Minnesota Wild |

| Detroit Pistons | Chicago Bears | Chicago Cubs | Nashville Predators |

| Toronto Raptors | Detroit Lions | Cincinnati Reds | St. Louis Blues |

| Philadelphia 76'ers | Green Bay Packers | Milwaukee Brewers | Winnipeg Jets |

| Milwaukee Bucks | Minnesota Vikings | Pittsburgh Pirates | Anaheim Ducks |

| Chicago Bulls | Atlanta Falcons | St. Louis Cardinals | Arizona Coyotes |

| New Orleans Pelicans | Carolina Panthers | Arizona Diamondbacks | Calgary Flames |

| Sacramento Kings | New Orleans Saints | Colorado Rockies | Edmonton Oilers |

| Phoenix Suns | Tampa Bay Buccaneers | Los Angeles Dodgers | Los Angeles Kings |

| Memphis Grizzlies | Arizona Cardinals | San Diego Padres | San Jose Sharks |

| Charlotte Hornets | Los Angeles Rams | San Francisco Giants | Vancouver Canucks |

| San Francisco 49ers | Las Vegas Golden Knights | ||

| Seattle Seahawks |

Benefits

In granting stadium subsidies, governments claim that the new or improved stadiums will have positive enternalities for the city. Proponents tout improvements to the local economy as the primary benefits. Economists who debate the issue have separated the effects on a local economy into direct and indirect effects. Direct benefits are those that exist as a result of the "rent, concessions, parking, advertising, suite rental, and other preferred seating rental", and direct expenses come from "wages and related expenses, utilities, repairs and maintenance, insurance," and the costs of building the facilities.[4] Generally, these benefits vary widely. The Balitmore Orioles, for example, estimate that each game they host brings $3 million in economic benefits to the city. Over the course of an entire baseball season, the Orioles will have 81 home games, which means that benefit gets multiplied to be around $243 million a season.[18] For NFL teams the case is much different, as there are only 8 home games a season. Over the lifetime of a stadium, which is often between 20-30 years, this benefit accumulates even more. Essentially, this is the basis on which municipalities evaluate the benefit of a team.

Supporters further argue that the stadiums attract tourism and businesses that lead to further spending and job creation, representing indirect benefits. All of the increased spending causes a multiplier effect that leads to more spending and job creation and eventually finances the subsidy through increased tax revenues from ticket and concessions sales, improved property values and more spending nearby the stadium.[31] In some cases, there has even been an observed reduction in crime during a game, although the aggregate effect of professional sports on crime is disputable.[32][33] Additionally, there has recently been research that suggests that home games generate what is called a "sunny day benefit".[34] There is a measurable drop in local spending that occurs within a city on a rainy day, but with a professional sports team playing a game, spending increases significantly. Jordan Rappaport, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas, estimates that this benefit is between $14 to $24 million dollars a year, which can be compounded over the life of a stadium.[35]

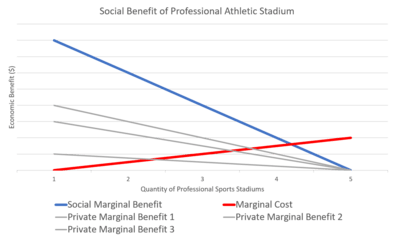

Advocates for stadium subsidies also claim less quantifiable positive externalities, such as civic pride and fan identification, so that hosting a major sports team becomes something of a public good. Local sports fans enjoy the benefit even if they do not pay for it.[31][36] When a city conducts a calculation to assess what they are willing to pay for a subsidy, they use an economic model that attempts to quantify the various social benefits for each dollar invested. This is done through a social marginal benefit evaluation, which takes the sums of all of the private benefits that result from investing, intended or not. Economists consider all the economic effects of having a professional athletic team in a city, like the "sunny day" benefit, job creation, civic pride, increased tourism, decreases/increases in crime rates, etc. The social marginal cost is equal to the sum of the private marginal benefits. The marginal cost is known only by the government, who deliberates with franchises to decide how much bringing a team to their city will cost. The image to the right is a good visual representation of this analysis. In this diagram, the city would like to acquire four teams, since at that point the social marginal benefit of recruiting a team still exceeds the marginal cost.

Criticisms

Many criticisms exist regarding the use of stadium subsidies. First, critics argue that new stadiums generate little to no new spending (consumption). Instead, what fans spend in and around the stadium are substitutes for what they would otherwise spend on different entertainment options. Thus, this argument contends, new stadiums do not cause economic growth or lead to increased aggregate income. In fact, this suggests that money being substituted towards concessions, tickets, and merchandise actively harms the economy surrounding a stadium.[37]

Another criticism of stadium subsidies is that much of the money the new stadiums bring in does not stay in the local economy. Instead of going to stadium employees and other sources that would benefit the local community, a lot of the money goes toward paying the organizations.[37] Those payments come from either the state or city government, where spending normally goes towards social welfare programs or salaries for government employees. It has been argued that the opportunity cost of a subsidy for a sports team is far greater than the benefit, since the billions of dollars that are spent on a stadium could be better spent on schools, firehouses, public transportation, or police departments.[10][1]

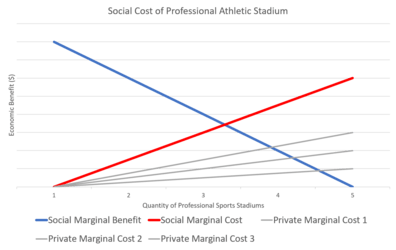

Critics also argue that the construction of new stadiums could cause citizens and businesses to leave a city because of eminent domain issues. If a city is forced to take land from its citizens to build a new stadium, those who have lost land could become angry enough to leave the city. If they are business owners, then they will likely take their businesses with them. These trade-offs are a part of the marginal cost calculation the city does. Much like the social marginal benefit calculation the city performed to find what benefits teams brought to the city, the social marginal cost calculation sums up all of the unintended negative effects from a particular spending plan.

A review of the empirical literature assessing the effects of subsidies for professional sports franchises and facilities reveals that most evidence goes against sports subsidies. Specifically, subsidies cannot be justified on the grounds of local economic development, income growth or job creation.[4][5][34][36]

See also

References

- 1 2 Kianka, Tim (6 March 2013). "Subsidizing Billionaires: How Your Money is Being Used to Construct Professional Sports Stadiums". Jeffrey S. Moorad Center for the Study of Sports Law. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- 1 2 Kuriloff, Aaron; Preston, Darrell (2012-09-05). "In Stadium Building Spree, U.S. Taxpayers Lose $4 Billion". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Fort, Rodney D. (2011). Sports Economics. Boston: Prentice Hall. pp. 408, 409. ISBN 9780136066026.

- 1 2 3 Baade, Robert A.; Dye, Richard F. (1990-04-01). "The Impact of Stadium and Professional Sports on Metropolitan Area Development". Growth and Change. 21 (2): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.1990.tb00513.x. ISSN 1468-2257.

- 1 2 Coates, Dennis (2007-10-01). "Stadiums and Arenas: Economic Development or Economic Redistribution?". Contemporary Economic Policy. 25 (4): 565–577. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7287.2007.00073.x. ISSN 1465-7287.

- ↑ Wolla, Scott (May 2017). "The Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums". Page One Economics.

- ↑ "Sports Stadiums". IMG Forum. January 31, 2017.

- ↑ Brown, T.M. "The Raiders Robbed Las Vegas In America's Worst Stadium Deal". Deadspin. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ↑ Kampis, Johnny. "Falcons' new home is just the latest of handouts to the NFL". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- 1 2 Long, Judith Grant (May 1, 2005). "The Real Cost of Funding for Major League Sports Facilities". Journal of Sports Economics. 6 – via SAGE Publications.

- ↑ Okner, B. “Subsidies of Stadiums and Arenas,” in Government and the Sports Business, edited by R. G.Noll. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1974, 325–48.

- ↑ Phelps, Zachary A. (2004). "Stadium Construction for Professional Sports: Reversing the Inequities Through Tax Incentives". Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 18 (3).

- ↑ "USC kicks off $270 million renovation of Coliseum - USC News". news.usc.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- ↑ Swayne, Linda E. (2011). Encyclopedia of Sports Management and Marketing. SAGE. ISBN 9781412973823.

- ↑ "USATODAY.com - N.Y./N.J. Super Bowl in 2008 may not come to pass". usatoday30.usatoday.com. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ↑ "Super Bowl LIII - Mercedes Benz Stadium". Mercedes Benz Stadium. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ John., Bale, (1993). Sport, space, and the city. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415080983. OCLC 26160156.

- 1 2 Noll, Andrew Zimbalist and Roger G. "Sports, Jobs, & Taxes: Are New Stadiums Worth the Cost?". Brookings. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ Isidore, Chris (2015-01-30). "NFL gets billions in subsidies from U.S. taxpayers". CNN. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ↑ Gillespie, Nick (2013-12-06). "Football: A Waste of Taxpayers' Money". Time, Inc. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ↑ Long, Judith Grant (May 1, 2005). "Full Count: The Real Cost of Public Funding For Major League Sports Facilities". Journal Of Sports Economics. 6: 119–143.

- ↑ "Here's how every NHL arena was funded". Flamesnation. 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ National Sports Law Institute at Marquette University Law School (June 12, 2012). "Major League Baseball" (PDF). Sports Facility Reports. 13.

- ↑ Center, StubHub. "About StubHub Center | StubHub Center". www.stubhubcenter.com. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ Snider, Rick (2017-02-09). "Maryland and D.C. politicians might have helped Virginia land the Redskins' next stadium". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ "Arena Facts - Pepsi Center". Pepsi Center. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ "Clippers owner Steve Ballmer announces '100 percent privately funded' arena". Sporting News. 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ "A Privately Financed Arena - NBA Style - An Experienced, Award-Winning Attorney Concentrating in the Areas of Real Estate & Sports Law". An Experienced, Award-Winning Attorney Concentrating in the Areas of Real Estate & Sports Law. 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ "Little Caesars Arena's funding mix not without critics". Detroit News. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- ↑ "Shedding more light on the United Center tax break". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- 1 2 Zimbalist, Andrew; Noll, Roger G (1997). "Sports, Jobs, & Taxes: Are New Stadiums Worth the Cost?". Brookings Institution. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Laqueur, Hannah; Copus, Ryan (2014-04-25). "Entertainment as Crime Prevention: Evidence from Chicago Sports Games". Rochester, NY.

- ↑ White, G. F., Katz, J., & Scarborough, K. E. (1992). The impact of professional football games upon violent assaults on women. Violence and Victims, 7(2), 157-71.

- 1 2 Rappaport, J., & Wilkerson, C. (2001). What are the benefits of hosting a major league sports franchise? Economic Review - Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 86(1), 55-86. Retrieved from http://ccl.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/218422373?accountid=10141

- ↑ Jordan Rappaport & Chad R. Wilkerson, 2001. "What are the benefits of hosting a major league sports franchise?," Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, issue Q I, pages 55-86.

- 1 2 Owen, Jeffrey G. (2006). "The Intangible Benefits of Sports Teams" (PDF). Public Finance and Management. 6 (3): 321–345.

- 1 2 Zaretsky, Adam M. (2001-04-01). "Should Cities Pay for Sports Facilities?". The Regional Economist. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved 2016-02-02.