St. Loman's Hospital, Mullingar

| St. Loman's Hospital | |

|---|---|

| Health Service Executive | |

Main block and entrance of the hospital | |

| |

| Geography | |

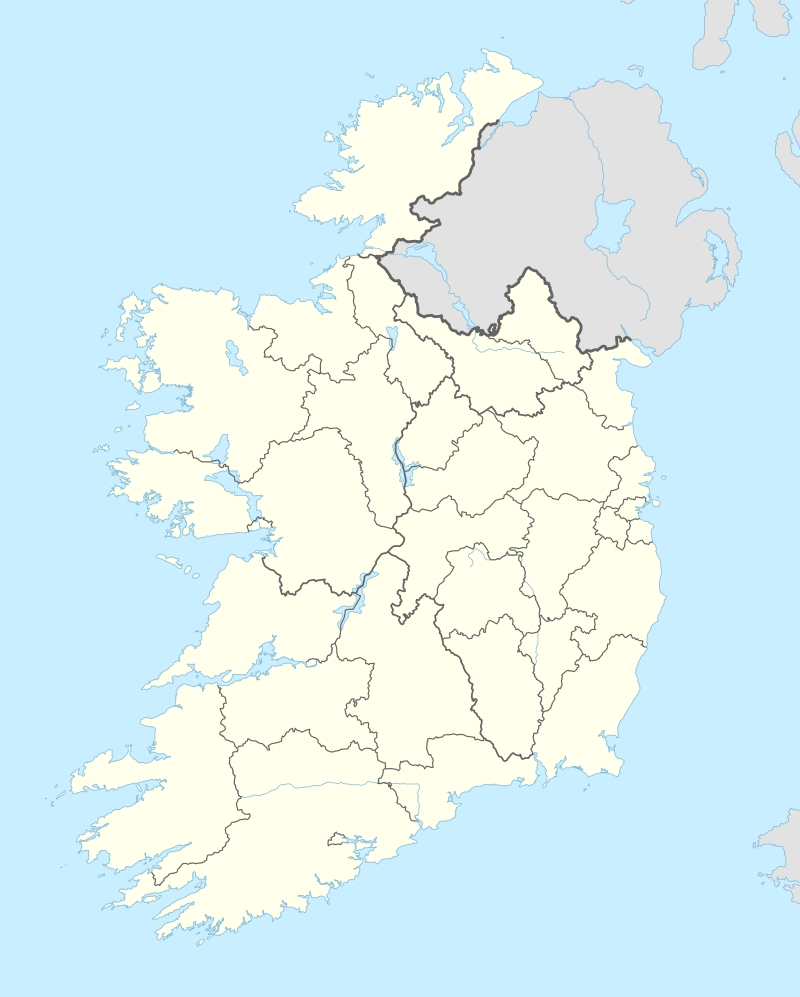

| Location | Delvin Road, Mullingar, Co. Westmeath, Ireland |

| Coordinates | 53°31′59.17″N 7°19′12.83″W / 53.5331028°N 7.3202306°WCoordinates: 53°31′59.17″N 7°19′12.83″W / 53.5331028°N 7.3202306°W |

| Organisation | |

| Funding | Government hospital |

| Hospital type | Psychiatric |

| Building details | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style |

|

| Opened | 23 August 1855 |

| Cost |

|

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | John Skipton Mulvany |

St. Loman's Hospital (formerly known as the Mullingar District Lunatic Asylum), is a psychiatric hospital located in Mullingar, Co. Westmeath. Opening on 23 August 1855,[1] it is the town's only psychiatric hospital and serves the Midlands. The hospital is infamous for the incarceration during the thirty-year period of 1940 to 1970 and the poor living standards which have since been improved by the owner, the HSE who purchased the hospital in 2006.

History

The hospital is a freestanding 41 bay, 3 storeyed psychiatric hospital built on twenty five acres of land purchased in 1848 for £829[1] which eventually opened in 1855 and was extended c.1895. The hospital is a well-detailed Victorian institutional complex, with Gothic style extensive Tudor Gothic detailing. The structure was built to designs by John Skipton Mulvany, possibly the most celebrated architect operating in Ireland at the time. It cost some £35,430 (equivalent to €44,986 in today's money) to build, and was built to accommodate 300 patients. The first patients were transferred from The Richmond Hospital in Dublin, and all of them were female.[2] On the grounds of the hospital, there are various buildings including a Primary Care Centre which was built c.1940[3] as a nurses' home where Tusla is now located alongside an Admissions office which was also built c.1940[4] and was originally used as an infirmary, a chapel which was constructed c.1886[5] and the Springfield Centre which offers pediatric and physiotherapy services.

Incarceration, and past treatment of patients

Julie Caffrey Leonard, a local housekeeper, was admitted into the hospital in 1895, aged 32, after she threw hot tea on her husband during an argument as she suspected him of adultery. She spent 22 years in the institution, and protested as she knew she did not belong in such a place, neither did most of those who were confined in its walls. She died in the hospital in 1917, aged 54.[6]

Hanna Greally was born in Athlone in 1925, and she was admitted to the hospital in 1943 at the age of 19 by the advice of her mother after Greally had just returned home from London where she had witnessed the horrors of the London Blitz while training to be a nurse. Bird's Nest Soup, a book written by Hanna and published in 1971, captured the haunting detail of other's lives stripped of human rights of "the unloved, social outcasts, the incurably embittered and the dispirited".[7] Greally died at her home in County Roscommon in 1987, aged 62.

"The patients inside, expectant, waited for the letters and the visits, until finally, one day, they would find themselves rejects, outcasts, and no explanation given. Sometimes a crushed spirit breaks, from mental agony and anguish, when she understands at last she is captive in a free society." —Bird's Nest Soup, 1971

In 1958, a time which was referred to as the "pinnacle of confinement", was reached in Ireland when 21,000 patients were being confined behind mental hospital walls across Ireland, 0.7% of the general population. Mortality rates were high, with more than 11,000 deaths every decade between the 1920–1960 period.[8] 1,304 bodies are reportedly buried in the grounds of the hospital, the last one being in 1970. As of 2011, they are unmarked, with numbered crosses being stored in an outbuilding.[9]

Inspector of Mental Health Services report

In 2007, the Inspector of Mental Health Services report created a horrific picture of the appalling conditions which some residents have to endure in ageing psychiatric hospitals around the country. The Inspector called for two hospitals to be closed, urging that St Loman's be closed immediately. The Inspector made the following comments on St. Loman's conditions.

"Apart from the admission units, the conditions in areas of St Loman's Hospital remained very poor with damp, peeling paint, tiles lifting on floors, poor sanitary facilities, curtains falling down and drab and institutional-style furnishings and decor. A significantly large number of these areas were dirty, including sluice rooms and bathrooms and toilets. In short, the conditions that people with enduring mental illness have to live in permanently in St Loman's Hospital were deplorable... every effort must be made to close the hospital immediately." —Inspector of Mental Health Services Report, 2007

In response to the report, the HSE kept the hospital open, admitting that the facilities there are "not what is required in the 21st century" and that "an upgrade of one of the blocks at St Loman's at a cost of €1.8 million, and secondly, the development of a 12 bed residential hostel for elderly clients with an enduring mental illness at a cost of €1.85 million" in 2008.[10] There has also been a long history of the admission of children and adolescents to adult units on the grounds of St. Loman's Hospital Mullingar.[11] This practice was not limited to St. Loman's Hospital but has long been the norm within the public mental health services of Ireland when accommodation for those minors cannot be met in appropriate child & adolescent units. The inspector for Mental Health Services has described this practice as "inexcusable and counter-therapeutic", while the founder of the Pieta House suicide prevention charity and senator Joan Freeman has described Ireland as being "in breach of all international regulations" in regards to this practice.[12] Ireland has thus far (2018) failed to put an end to the admission of children and adolescents to "adult-only" psychiatric units despite rules introduced by the mental health commission to end the practice.

Dr Muthulingam Kasiraj

In 2016, a Medical Council inquiry had found a junior doctor, Dr Muthulingam Kasiraj, also known as Dr Sripathy, who had worked as a senior house officer at St Loman's Psychitric hospital for a period of approximately six months between July 2013 and January 2014, guilty of poor professional performance on several counts.[13] Allegations made against the doctor included that he did not have basic knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), did not know the difference between some generic and branded drugs, did not know how to dial 999, was incapable of interpreting simple blood tests, did not understand the effects of some drugs on the liver, and that he wrote up wrong doses for drugs (supposedly no patients were harmed).[14] Mr Kasiraj was also accused of being responsible for incomplete note taking[15]. In Mr Kasiraj's defence, he claimed that anankastic personality disorder, which he was diagnosed with after the time period in question, had "affected" his performance during the period in question.[16] Mr Kasiraj had worked in the child and adolescent psychiatric services in Mullingar for the approximate six months prior to securing his position at St Loman's Psychiatric Hospital.[17] It has not been reported as to whether his incompetence may have also pervaded his work with children and adolescents as the inquiry focused on allegations in regards to his work at St Loman's Psychiatric Hospital.

References

- 1 2 D.),, Kelly, Brendan (Brendan (2016). Hearing voices : the history of psychiatry in Ireland. Newbridge, Co. Kildare, Ireland: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9781911024347. OCLC 962795296.

- ↑ "St. Loman's Hospital, Delvin Road, Mullingar, County Westmeath: Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". www.buildingsofireland.ie. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ↑ "Forbes Family Vault Additional Images: Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". www.buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ "Additional Images: Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". www.buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ "Additional Images: Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". www.buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ Healy, Catherine. "The woman who was committed to an asylum after throwing tea at her husband". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ↑ O'Brien, Carl (16 June 2014). "Ireland's mental hospitals: the last gap in our history of 'coercive confinement'?". Irish Times. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Well Said Productions, Remembering Hanna Greally Part 2, retrieved 2018-03-18

- ↑ "Bird's Nest Soup". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ↑ Hunter, Niall (10 June 2008). "HSE keeps condemned mental hospitals open". IrishHealth. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ↑ "Children forced to stay in adult psychiatric units - Independent.ie". Independent.ie. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ "Children admitted to adult psychiatric units despite new rules to cease practice". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ "Doctor who didn't know simple CPR found guilty of poor performance - Independent.ie". Independent.ie. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ "Doctor 'didn't know how to call 999', Medical Council told". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ↑ "Doctor guilty of poor professional performance". RTE.ie. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ Murphy, Darragh Peter. "Medical doctor 'didn't know a malignant melanoma was a skin condition'". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ "Doctor 'didn't know how to call 999', Medical Council told". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2018-04-04.