South-South cooperation in science

South-South cooperation is cooperation between two or more developing countries. This article monitors recent developments in South-South cooperation in the field of science and technology.

Role of regional economic communities

Regional economic communities have become a conduit for South–South cooperation in science, technology and innovation. Many of these economic communities have taken inspiration from the European Union model.[1][2]

Increasingly, the long-term economic plans adopted by regional communities in the South are accompanied by a policy or strategy for science. For instance, the Policy on Science and Technology (ECOPOST) adopted in 2011 by the Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) ‘is an integral part of Vision 2020’, the subregion’s development blueprint to 2020.[3]

A world increasingly characterized by economic blocs

It has been argued that ‘the increasingly urgent requirement is for Africa to engage in a unified manner in a world that is increasingly characterized by economic blocs and large emerging economic powers’ and that ‘the most formidable obstacle of all to regional integration [in Africa] is probably the resistance of individual governments to relinquishing any national sovereignty’.[4]

The President of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and former chair of the Caribbean Common Market (Caricom), Ralph Consalves, echoed this sentiment in a speech he gave in 2013. ‘It is evident… that our region would find it more difficult by far to address its immense current and prospective challenges, unless its governments and peoples embrace strongly a more mature, more profound regionalism’.

The mood in sub-Saharan Africa is clearly towards greater regional integration. However, economic integration is being hampered by the similar structure of economies (minerals and agriculture), poor economic diversification and low levels of intraregional trade: just 12% of total African trade, compared to about 55% in Asia and 70% in Europe. Science is seen as a way of fostering regional economic integration, as it will enable countries to diversify their economies and develop intraregional trade.

The continent is currently preparing the groundwork for the African Economic Community, which is to be in place by 2028. To this end, regional communities are consolidating ties. The five members of the East African Community (Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda), for instance, formed a common market in 2010. They plan to establish a common currency by 2023 and are developing a Common Higher Education Area that has been inspired by the European Union model. In 2015, the East African Community signed a Tripartite Free Trade Agreement with the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa grouping 20 states and the SADC grouping 15 states.[3][5]

The Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) was founded in 1992, shortly after the distantegration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, in order to develop prosperity and security in the region. One of its goals is to deepen ties with the European Commission in Brussels. The Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs is the BSEC's central decision-making body. There is also a Parliamentary Assembly modelled on the Council of Europe and a Permanent International Secretariat, based in Istanbul. The BSEC has a Business Council made up of experts and representatives of Chambers of Commerce from the member states and a Black Sea Trade and Development Bank which receives support from the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[6]

The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR).only became a legal entity in 2011. Like others before it, UNASUR is modelled on the European Union and, thus, embraces the free movement of goods, services, capital and people among its 12 members. UNASUR plans to establish a common parliament and currency. Governments have also been discussing the idea of standardizing university degrees in member countries. Rather than creating other new institutions, UNASUR plans to rely on existing trade blocs like the Common Market for the South (Mercosur) and the Andean Community.[7]

Some voices from within the Gulf have suggested transforming the Gulf Cooperation Council into a regional socio-economic and political bloc that would also be modelled on the European Union.[8]

Scientific integration part of regional economic integration

The East African Community’s Common Market Protocol (2010) makes provision for market-led research, the promotion of industrial research and the transfer, acquisition, adaptation and development of modern technology. States are encouraged to collaborate with the East African Science and Technology Commission and to establish a research and technological development fund for the purpose of implementing the provisions in the protocol.[1][5][3]

The Strategic Plan for the Caribbean Community 2015–2019 proposes reinforcing regional integration by adopting a common foreign policy and embracing research and innovation. To improve co-ordination among the four existing regional organizations (Caribbean Science Foundation, Cariscience, Caribbean Academy of Sciences and Caribbean Council for Science and Technology), the Prime Minister of Grenada, Keith Mitchell, who is also responsible for science and technology within Caricom, set up the Caricom Science, Technology and Innovation Committee in 2014.[9]

Even though the focus of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) has always been on the creation of a single market along the lines of the European model, ‘leaders have long acknowledged that successful economic integration will hinge on how well member states manage to assimilate science and technology’. When ASEAN’s Vision 2020 was adopted in 1997, its stated goal ‘was for the region to be technologically competitive by 2020’.[10]

ASEAN’s Plan of Action on Science, Technology and Innovation 2016–2020 ‘aims to strengthen scientific capacity in member states by fostering exchanges among researchers both within the region and beyond’. The new ASEAN Economic Community is expected to spur scientific cooperation among member countries, while enhancing the role of the ASEAN University Network, which already counts 30 members.[2][11][12]

The Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) has adopted three Action Plans on Cooperation in Science and Technology (2005-2009, 2010-2014 and 2014-2018). The second Action Plan was funded on a project basis, since the plan had no dedicated budget. Two key projects were funded by the European Union in 2008 and 2009, namely the Scientific and Technological International Cooperation Network for Eastern European and Central Asian Countries (IncoNet EECA) and the Networking on Science and Technology in the Black Sea Region project (BS-ERA-Net).[6]

Not all the more established regional economic communities have enjoyed the same level of success. For instance, ‘since its inception in 1985, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has failed to emulate the success of [ASEAN] in fostering regional integration in trade and other areas, including in science, technology and innovation... South Asia remains one of the world’s least economically integrated regions, with intraregional trade accounting for merely 5% of total trade’.[13]

The South Asian University, which opened its doors in 2010 with the intention of becoming a centre of excellence, is the exception which confirms the rule. The university is hosted by India but all SAARC members share the operational costs in mutually agreed proportions. Admission is governed by a quota system, with students paying heavily subsidized tuition fees. In 2013, the university received 4 133 applications from all eight SAARC countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan), double the number in 2012. There were 500 applications alone for the 10 places on offer for the doctoral programme in biotechnology.[13]

In other regions, some strategies have encountered hurdles that may affect implementation. This is the case of the Protocol on Science, Technology and Innovation, for instance; it was adopted by all 15 members of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) in 2008 but, by 2015, had only been ratified by four: Botswana, Mauritius, Mozambique and South Africa. The protocol was able to enter into force in June 2017, once two-thirds of member states had ratified it. Although the South African Department of Science and Technology described the protocol, in a 2011 briefing, as ‘an essential first step towards regional integration, with steady growth in self-financed bilateral cooperation’, it also found the regional desk for science, technology and innovation to be ‘under-resourced and mostly ineffectual’, making ‘member states reluctant to support it’.[4]

BSEC's Third Action Plan on Science and Technology 2014-2018 acknowledges that considerable effort has been devoted to setting up a Black Sea Research Programme involving both BSEC and European Union members but also that, ‘in a period of scarce public funding, the research projects the Project Development Fund could support will decrease and, as a result, its impact will be limited. Additional efforts are needed to find a solution for the replenishment of the Project Development Fund’.[14]

The current roadmap for the Arab region is the Arab Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation. It was endorsed in 2014 by the Council of Ministers of Higher Education and Scientific Research in the Arab World. The Strategy urges countries to engage in greater international cooperation in 14 scientific disciplines and strategic economic sectors, including nuclear energy, space sciences and convergent technologies such as bio-informatics and nanobiotechnology. ‘The Strategy nevertheless eludes some core issues, including the delicate question of who will foot the hefty bill of implementing' it.[8]

The Arab States in Asia experienced the fastest growth in international scientific collaboration (+199%) of any region between 2008 and 2014. Five developing Arab economies count one or more developing countries among their top five partners: Iraq (Malaysia and China), Libya (India), Oman (India), Palestine (Egypt and Malaysia) and Yemen (Malaysia and Egypt).[8]

The Gulf Cooperation Council has encouraged its members to diversify their economies for the past 30 years, during which time Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have all developed non-oil sectors. The United Arab Emirates has been advocating the creation of a pan-Arab space agency for years. Together with the Korean company Satrec Initiative, the Emirates Institution for Advanced Science and Technology placed its first Earth-observation satellite in orbit in 2009, followed by a second in 2013 and, if all goes according to plan, a third in 2017.

Industrial development a key focus of South–South cooperation

Multilateral scientific cooperation

Countries of the South are collaborating in fields with industrial potential. One interesting example within the Mercosur space (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela) is the Biotech project. It has been designed to take better advantage of existing research skills to foster competitiveness in productive sectors. The second phase, Biotech II, addresses regional projects in biotechnological innovation linked to human health (diagnosis, prevention and the development of vaccines against infectious diseases, cancer, type 2 diabetes and autoimmune diseases) and biomass production (traditional and non-traditional crops), biofuel elaboration processes and evaluation of its by-products. New criteria have been incorporated to respond to demand from participating consortia for a greater return on investment and the participation of more partners, such as from Europe.[7]

Bio-industry is also the focus of the Innovative Biotechnologies Programme (2011–2015), which was established by the Eurasian Economic Community (since superseded by the Eurasian Economic Union in January 2015). Within this programme, prizes were awarded at an annual bio-industry exhibition and conference. In 2012, 86 Russian organizations participated, plus three from Belarus, one from Kazakhstan and three from Tajikistan, as well as two scientific research groups from Germany.It is noteworthy that an oil-rent economy like Kazakhstan participated in this programme. For Vladimir Debabov, Scientific Director of the Genetika State Research Institute for Genetics and the Selection of Industrial Micro-organisms in the Russian Federation, ‘in the world today, there is a strong tendency to switch from petrochemicals to renewable biological sources. Biotechnology is developing two to three times faster than chemicals.’[15]

In 2013, the Russian, Belarusian and Kazakh governments pooled their resources to create a Centre for Innovative Technologies. Selected projects sponsored by the centre are entitled to funding of US$3–90 million each and are implemented within a public–private partnership. The first few projects approved focused on supercomputers, space technologies, medicine, petroleum recycling, nanotechnologies and the ecological use of natural resources. Once these initial projects have spawned viable commercial products, it is planned to reinvest the profits in new projects.[15]

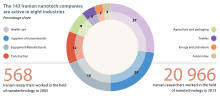

Nanotechnology is a focus of South–South cooperation led by Iran. In 2008, Iran’s Nanotechnology Initiative Council established an Econano network to promote the scientific and industrial development of nanotechnology among fellow members of the Economic Cooperation Organization, namely Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.[16]

Bilateral scientific cooperation

Bilateral scientific cooperation, too, can often have an industrial focus. India and Sri Lanka, for instance, set up a Joint Committee on Science and Technology in 2011, along with an Indo-Sri Lankan Joint Research Programme. The first call for proposals in 2012 covered research topics in food science and technology; applications of nuclear technology; oceanography and Earth science; biotechnology and pharmaceuticals; materials science; medical research, including traditional medical systems; and spatial data infrastructure and space science. Two bilateral workshops were held in 2013 to discuss potential research collaboration on transdermal drug delivery systems and clinical, diagnostic, chemotherapeutic and entomological aspects of Leishmaniasis, a disease prevalent in both India and Sri Lanka that is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected sandflies.[13]

The BRICS (Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa) tend to engage in bilateral collaboration on scientific projects. There is ‘dynamic bilateral collaboration’ between China and the Russian Federation, for instance. This cooperation stems from the Treaty on Good Neighbourliness, Friendship and Co-operation signed by the two countries in 2001, which has given rise to regular four-year plans for its implementation. Dozens of joint large-scale projects are being carried out. They concern the construction of the first super-high-voltage electricity transmission line in China; the development of an experimental fast neutron reactor; geological prospecting in the Russian Federation and China; and joint research in optics, metal processing, hydraulics, aerodynamics and solid fuel cells. Other priority areas for co-operation include industrial and medical lasers, computer technology, energy, the environment and chemistry, geochemistry, catalytic processes and new materials.[17]

The Russian Federation and China are also cooperating in the field of satellite navigation, through a project involving Glonass (the Russian equivalent of GPS) and Beidou (the regional Chinese satellite navigation system). They have also embarked on a joint study of the planets of our Solar System. A resident company of the Skolkovo Innovation Centre, Optogard Nanotech (Russian) signed a long-term deal with the Chinese Shandong Trustpipe Industry Group in 2014 to promote Russian technologies in China. In 2014, Moscow State University, the Russian Venture Company and the China Construction Investment Corporation (Chzhoda) also signed an agreement to upscale cooperation in developing technologies for ‘smart homes’ and ‘smart’ cities’.[17]

The UNESCO Science Report observes that ‘we are seeing a shift in Russo–Chinese collaboration from knowledge and project exchanges to joint work'. Since 2003, joint technoparks have been operating in the Chinese cities of Harbin, Changchun and Yantai, among others. Within these technoparks, there are plans to manufacture civilian and military aircraft, space vehicles, gas turbines and other large equipment using cutting-edge innovation, as well as to mass-produce Russian technologies developed by the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. One new priority theme for high-tech co-operation concerns the joint development of a new long-range civil aircraft.[17]

Cooperation in space science

The China–Brazil Earth Resources Satellites (CBERS) programme embraces a family of remote-sensing satellites built jointly by Brazil and China which provide coverage of the world´s land areas. CBERS-1 functioned from October 1999 to July 2003, CBERS-2 from October 2003 to June 2008 and CBERS-2B from September 2007 to May 2010. CBERS-3 was launched in 2011 and CBERS-4 in 2014. CBERS-3 and CBERS-4 are each equipped with four cameras with bands in visible, near-infrared, middle and thermal infrared Brazil and China share the responsibility for, and cost of, building the satellites. In Brazil, the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) designs half of the subsystems and contracts them to the Brazilian space industry. As of 2010, the Brazilian participation in the programme amounted to a total cost of about US$ 500 million, with 60% of investment taking the form of industrial contracts. Data obtained from the CBERS satellites are released within a free and open data policy. From 2004 to 2010, more than 1.5 million images were delivered to users in Brazil, Latin America and China. These images have applications in forestry and agriculture assessment, urban management and geological mapping. Brazil uses the images to survey deforestation in Amazonia and to assess land use associated with cash crops such as sugarcane and soybeans and with large-scale cattle ranching. China and Brazil have agreed on a joint strategy for facilitating international access to remotesensing data in Africa. Since 2012, African ground stations in South Africa, the Canary Islands, Egypt, and Gabonhave been receiving CBERS data which they are entitled to share. The CBERS programme thus enables Brazil and China to contribute to global environmental policy-making.[18]

The joint Argentinian–Brazilian SABIA-MAR Earth observation satellite mission will be studying ocean ecosystems, carbon cycling, marine habitats mapping, coasts and coastal hazards, inland waters and fisheries. Also under development in 2015 was the new SARE series designed to expand the active remote observation of Earth through the use of microwave and optical radars.[7]

Development of African networks of centres of excellence

A central strategy of Africa’s Science and Technology Consolidated Plan of Action (CPA) for 2005–2014 was to establish networks of centres of excellence across the continent. A decade on, these centres are one of the plan’s success stories, according to an expert review of the CPA.[5][19]

Most of these networks focus on biosciences. Four networks of centres of excellence have been established in Egypt, Kenya, Senegal and South Africa within the African Biosciences Initiative, whereby participating institutes offer their facilities for subregional use.Two complementary networks based in Kenya and Burkina Faso focus on improving agricultural techniques and developing agro-processing, in the case of Bio-Innovate, and on helping regulators deal with safety issues related to the introduction and development of genetically modified organisms, in the case of the African Biosafety Network of Expertise.[3][5]

A network of five African Institutes of Mathematical Sciences has also taken root. The first one opened in South Africa in 2003 and the remainder in Senegal, Ghana, Cameroon and Tanzania between 2012 and 2014. Each offers postgraduate education, research and outreach. The plan now is for a vast network of 15 such centres across Africa, within a scheme known as the Next Einstein Initiative. The Government of Canada made a US$20 million investment in the project in 2010 and numerous governments in Africa and Europe have followed suit.[4]

These networks have an Achilles tendon, though, since many are reliant on donor funding for their survival. The biosciences hub in Kenya for East and Central Africa, for instance, relies on support from the Australian, Canadian and Swedish governments, as well as from partners such as the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. A 2014 evaluation concluded that the hub remained ‘financially vulnerable’.[5]

‘With hardly any African governments having raised domestic research spending to the target level of 1% of GDP, more than 90% of funding mobilized for implementation of the CPA came from bilateral and multilateral donors’, concluded the expert review of the CPA. The review also noted that ‘the failure to set up the African Science and Technology Fund was one of the landmark and visible weaknesses in implementation of the CPA’. Although the continent’s roadmap for the next decade, the Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa to 2024 (STISA-2024), considers it ‘urgent to set up such a fund’, it identifies no specific funding mechanism – even though STISA ‘places science, technology and innovation at the epicentre of Africa’s socio-economic development and growth’.[19][5][20]

In 2012, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) designated 14 centres of excellence in member countries, namely Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger and Togo. This label entitles these institutions to financial support from WAEMU for a two-year period. ECOWAS intends to establish several centres of excellence of its own on a competitive basis, within its own Policy on Science and Technology (ECOPOST).[3]

South Africa: soft power through science

South Africa is a regional powerhouse, since it alone generates about one-quarter of African GDP. In 2012, South Africa invested in more new projects across the continent than any other country in the world.[4]

Through the Department of Science and Technology, South Africa has entered into 21 formal bilateral agreements with other African countries in science and technology since 1997, most recently with Ethiopia and Sudan in 2014. Within three-year joint implementation plans which define spheres of common interest, cooperation tends to take the form of joint research calls and capacity-building through information- and infrastructure-sharing, workshops, student exchanges, development assistance and so on.[4]

Space science and technology are a focus of bilateral cooperation for 10 out of the 21 countries. In 2012, South Africa and Australia won a bid to build the world’s largest radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), at a cost of €1.5 billion. South Africa is working with eight African partners in this area, six of them from within the SADC: Botswana, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia and Zambia. The other two are Ghana and Kenya.[4]

Through the African SKA Human Capital Development Programme, South Africa has also been co-operating with other SADC countries in skills training since 2005. In 2012, the programme awarded about 400 grants for studies in astronomy and engineering from undergraduate to postdoctoral levels, while also investing in training programmes for technicians. Courses in astronomy are being taught in Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius and Mozambique.[4]

This work is complemented by an agreement signed in 2009 between Algeria, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa for the construction of three low-Earth orbiting satellites within the African Resource Management Constellation (ARMC). South Africa will build at least one out of the three, construction of which (ZA-ARMC1) began in 2013. This cooperation should develop Africa’s technological and human capacities in Earth observation, for use in urban planning, land cover mapping, disaster prediction and monitoring, water management, oil and gas pipeline monitoring and so on.[4]

Table: South Africa's bilateral scientific cooperation in Africa, 2015

| Co-operation agreement (signed) | Skills | STI policy/

Intellectual property |

Biosciences

/Biotech |

Agriculture

/Agro-processing |

Aeronautics

/Space |

Nuclear medical /laser tech | Mining/

Geology |

Energy | ICTs | Environment / climate change | Indigenous knowledge | Material sciences/ nanotech | Basic sciences/

Maths |

| Angola (2008) | √ | ||||||||||||

| Botswana (2005)* | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Lesotho (2005) | √ | ||||||||||||

| Malawi (2007) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Namibia (2005)* | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Mozambique (2006)* | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Algeria (1998) | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Egypt (1997) | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Ethiopia (2014) | |||||||||||||

| Tunisia (2010) | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Kenya (2004)* | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Uganda (2009) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Sudan (2014) | |||||||||||||

| Tanzania (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Rwanda (2009) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Senegal (2009) | |||||||||||||

| Nigeria (2001) | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Ghana (2012)* | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Mali (2006) | |||||||||||||

| Zambia (2007)* | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Zimbabwe (2007) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

*partner of African Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network and of Square Kilometre Array

Source: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (2015), Table 20.6, based on data from South African Department of Science and Technology

International centres fostering South–South cooperation

Increasingly, countries of the South are fostering cooperation in science and technology through regional or international centres. Many of these centres function under the auspices of United Nations agencies. The following are some examples.

The International Science, Technology and Innovation Centre for South–South Cooperation (ISTIC) was set up in Malaysia in 2008 under the auspices of UNESCO. In 2014, Cariscience ‘pushed back its boundaries’ by running a training workshop in Tobago on Technopreneurship for the Caribbean, in partnership with ISTIC.[9]

Since 2011, China has set up two centres which function under the auspices of UNESCO. The first is the Regional Training and Research Centre on Ocean Dynamics and Climate, which has been training young scientists from Asian developing countries, in particular, since 2011, at no cost to the beneficiary. The second is the International Research and Training Centre for Science and Technology Strategy, inaugurated in Beijing in September 2012. It designs and conducts international co-operative research and training programmes in such areas as indicators and statistical analysis, technology foresight and roadmapping, financing policies for innovation, the development of small and medium-sized enterprises and strategies for addressing climate change and sustainable development.[21]

India hosts the Regional Centre for Biotechnology, the first of its kind in South Asia. Established under the auspices of UNESCO in 2006, the centre is part of the Biotech Science Cluster being built in Faridabad by the Department of Biotechnology. It offers specialized training and research programmes in new opportunity areas, such as cell and tissue engineering, nanobiotechnology and bioinformatics, with an emphasis on interdisciplinarity.[22]

In 2012, an International Centre for Biotechnology was established under the auspices of UNESCO at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka. The institute provides high-level training (including at subregional level), education and research, particularly in areas related to food security, conservation of harvested crops, gene banking and tropical diseases.[3]

The West Africa Institute is the fruit of a public–private partnership involving ECOWAS, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), UNESCO, the pan-African Ecobank and the Government of Cabo Verde. This think tank was established in Praia (Cabo Verde) in 2010, to provide the missing link between policy and research in the regional integration process. The institute is a service provider, conducting research for regional and national public institutions, the private sector, civil society and the media.[3]

Iran hosts several international research centres, including the following, which function under the auspices of United Nations bodies: the Regional Centre for Science Park and Technology Incubator Development (UNESCO, est. 2010), the International Centre on Nanotechnology (UNIDO, est. 2012) and the Regional Educational and Research Centre for Oceanography for Western Asia (UNESCO, est. 2014).[16]

Iran is one of nine members of a new centre which uses Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (SESAME). Most of the other eight members are developing economies: Bahrain, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority and Turkey.[8]

SESAME’s mission is to provide a world-class research facility for the region, while fostering international scientific cooperation. SESAME was established under the auspices of UNESCO before becoming a fully independent intergovernmental organization in its own right. Construction of the centre began in Jordan in 2003. Now fully operational, the centre is being officially inaugurated in May 2017.[8]

Synchrotrons have become an indispensable tool for modern science. They work by accelerating electrons around a circular tube at high speed, during which time excess energy is given off in the form of light. The light source acts like a super X-ray machine and can be used by researchers to study everything from viruses and new drugs to novel materials and archaeological artefacts. There are some 50 such storage-ring based synchrotrons in use around the world. Although the majority are found in high-income countries, Brazil and China also have them.[8]

Sources

![]()

References

- 1 2 UNESCO (2015). UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 Soete, Luc; Schneegans, Susan; Erocal, Deniz; Baskaran, Angathevar; Rasiah, Rajah (2015). A world in search of an effective growth strategy. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Essegbey, George; Diaby, Nouhou; Konte, Almamy (2015). West Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kraemer-Mbula, Erika; Scerri, Mario (2015). Southern Africa. In UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Urama, Kevin; Muchie, Mammo; Twiringiyimana, Remy (2015). East and Central Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 Eröcal, Deniz; Yegorov, Igor (2015). Countries in the Black Sea basin. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 Lemarchand, Guillermo A. (2015). Latin America. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zoubi, Moneef; Mohamed-Nour, Samia; El-Kharraz, Jauad; Hassan, Nazar (2015). Arab States. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3100129-1.

- 1 2 Ramkissoon, Harold; Kahwa, Ishenkumba A. (2015). Caricom. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Rasiah, Rajah; Chandran, V.G.R. Malaysia. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. p. 689. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Korku Avenyo, Elvis; et al. (2015). Tracking trends in innovation and mobility. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Turpin, Tim; Zhang, Jing A.; Burgos, Bessie M.; Amaradsa, Wasantha (2015). Southeast Asia and Oceania. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 Nakandala, Dilupa; Malik, Ammar A. (2015). South Asia. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (2014). Third Action Plan on Science and Technology, 2014-2018 (PDF). Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation.

- 1 2 Mukhitdinova, Nasiba (2015). Central Asia. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. pp. 368, Box 14.1. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 Ashtarian, Kioomars (2015). Iran. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 Gokhberg, Leonid; Kuznetsova, Tatiana (2015). Russian Federation. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ UNESCO Science Report: the Current Status of Science around the World. Paris: UNESCO. 2010. p. 118. ISBN 978-92-3-104132-7.

- 1 2 AMCOST (2013). Review of Africa's Science and Technology Consolidated Plan of Action, 2005-2014. Final draft. Study by expert panel commissioned by African Ministerial Conference on Science and Technology.

- ↑ African Union/NEPAD (2014). Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa to 2024 (PDF).

- ↑ Cao, Cong (2015). China. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Mani, Sunil (2015). India. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.