Sonnet 25

| Sonnet 25 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

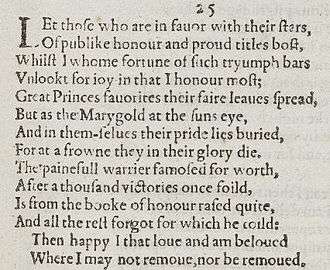

Sonnet 25 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

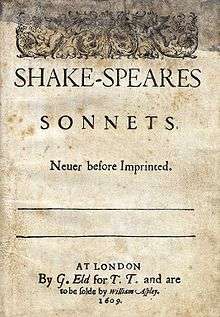

Sonnet 25 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in the Quarto of 1609. It is a part of the Fair Youth sequence.

In the sonnet the poem expresses the poet's contentedness in comparison to others, though they may have titles, honors, or are favored at court, or are noted warriors. It prefigures the more famous treatment of class differences found in Sonnet 29. There are noted similarities in this sonnet and in the relationship of Romeo and Juliet.

Synopsis

Q1 The Speaker contrasts those who are fortunate (whether by the astrological influence of real "stars", or the social influence of their superiors, metaphorical "stars") with himself who, favored with no such public recognition, nevertheless can revel ("joy" is used as a verb) in what he holds most dear. Q2 These seeming fortunates display their "pride" (i.e. self-esteem, or finery)[2] like an opening marigold, but only so long as their prince ("sun") favors them. (Elizabethans knew the marigold as a flower that opened in the presence, and closed in the absence, of the sun.[3]) Q3 Similarly, even a warrior renowned for "a thousand victories" may be stripped of his honor and forgotten after a single defeat. C But the Speaker is happy in his mutual love, from which he cannot be removed, either by himself or by others.

Structure

Sonnet 25 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet, formed of three quatrains and a final couplet in iambic pentameter, a type of metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 12th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / And all the rest forgot for which he toil'd: (25.12)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The 10th line begins with a common metrical variant, the initial reversal:

/ × × / × / × / × / After a thousand victories once foil'd, (25.10)

The 6th line also has a potential initial reversal, as well as the rightward movement of the fourth ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

/ × × / × / × × / / But as the marigold at the sun's eye, (25.6)

Potential initial reversals also occur in lines 1 and 11, with line 8 potentially exhibiting both an initial and midline reversal. Minor ionics appear in lines 2 and 3.

The meter demands a few variant pronunciations: line 3's "favourites" functions as 3 syllables, and line 9's "warrior" as 2 syllables.[2] The final -ed is syllabic in line 7's 3-syllable "burièd", line 9's 3-syllable "famousèd" and line 11's 2-syllable "razèd".[4] Stephen Booth notes that the original typography suggests that the final rhymes may have been intended to be trisyllabic: "belovèd" and "removèd",[2] although other editors (like John Kerrigan) prefer the standard 2-syllable pronunciations.[5]

Emendations

This sonnet, as originally printed, departs from the English sonnet's typical rhyme scheme, abab cdcd efef gg. Lines 9 and 11 (the expected e lines) do not rhyme. These lines in the Quarto of 1609 read (with emphasis added):

The painefull warrier famoſed for worth,

...

Is from the booke of honour raſed quite,[6]

No other lines in Shakespeare's Sonnets fail to rhyme, and Shakespeare's typical sonnet structure demands that these lines should rhyme with each other. Most editors emend one or the other of these words to form one of three rhyming pairs:

- fight – quite — first suggested by Lewis Theobald[3] and "the more popular of the two generally favored emendations".[2]

- might – quite — first suggested by Edward Capell[3] and the second most popular according to Booth.[2]

- worth – forth — also suggested by Theobald.[3] This emendation was preferred by John Payne Collier.[7]

Duncan-Jones sees weaknesses in all three emendations, and retains the Quarto's non-rhyming pair worth – quite.[8] George Steevens opined that "this stanza is not worth the labour that has been bestowed on it."[7]

Analysis

Astrological References

Shakespeare refers to the influences of astrology and fate in this poem. Stars are cited as the luck-giving ones that favor some with positions at court. The reference made to the "favour of the stars" is also a metaphor for the members of the court keeping in favour of the King.[9] Because courtly status is gifted by the stars and not earned, it is precarious.[10] John Kerrigan notes the echo of the prologue to Romeo and Juliet in the astrological metaphor of the first quatrain; he notes that the image severs reward from justice, making fortune a mere caprice.

Marigold Metaphor

_4.01_page_209.png)

Edward Dowden notes that the marigold was most commonly mentioned in Renaissance literature as a heliotrope, with the various symbolic associations connected to that type of plant; William James Rolfe finds an analogous reference to the plant in George Wither's poetry:[7]

When, with a serious musing, I behold

The gratefull, and obsequious Marigold,

How duely, ev'ry morning, she displayes

Her open breast, when Titan spreads his Rayes; ...

How, when he downe declines, she droopes and mournes,

Bedew'd (as 'twere) with teares, till he returnes; ... (lines 1-4, 7-8)[11]

but whereas for Wither the sun represents God and the marigold's reliance upon it is a virtue, Shakespeare's "sun" is mortal and fickle and reliance upon this sun is a risk. Edmond Malone noted the resemblance of lines 5-8 to this section of Wolsey's farewell in Henry VIII:[7]

This is the state of man: to-day he puts forth

The tender leaves of hopes, to-morrow blossoms,

And bears his blushing honors thick upon him;

The third day comes a frost, a killing frost,

And when he thinks, good easy man, full surely

His greatness is a-ripening, nips his root,

And then he falls as I do. (III.ii.352-358)[12]

Ironically, this passage is now widely (though not universally) held to have been written by John Fletcher.[13]

Essex's Rebellion, style of allusion, and "compensation"

In Sonnet 25 may allude to Essex's Rebellion.[14] In Themes and Variations in Shakespeare's Sonnets (1961), James Blair Leishman criticised preceding approaches to Shakespeare's sonnets, feeling they either excessively focussed on the identity of "W.H.", the Fair Youth, the Rival Poet, or the Dark Lady; or they analysed the sonnets' style in isolation. To remedy this perceived lack, Leishman sets out to analyse the sonnets by comparison and contrast with other poets and sonneteers like Pindar, Horace and Ovid; Petrarch, Torquato Tasso, and Pierre de Ronsard; and Shakespeare's English predecessors and contemporaries Edmund Spenser, Samuel Daniel, Samuel Daniel, and John Donne.[15] Here Leishman agrees that the sonnet contains such allusions, but argues that it is more likely to have been written, and the allusions being to, the state of affairs shortly after Essex's return from Ireland in 1599—as opposed to after Essex's trial and execution in 1601—when the issue was fresh in Shakespeare's mind. In this interpretation, Essex is the "painful warrior famoused for fight" who "After a thousand victories" in Ireland "Is from the book of honor razed quite, / And all the rest forgot for which he toil'd:".[16]

Leishman also names Sonnet 25 as an example of a contrast between the style of Shakespeare's sonnets and Drayton: where Drayton directly names the people he refers to, and references public events "in a perfectly plain and unambiguous manner,"[16] Shakespeare never directly includes names and all his allusions to public events are couched in metaphor. He draws a comparison to Dante Alighieri and calls the style "Dantesquely periphrastic".[16]

In Leishman's critical framework, Sonnets 25, 29 and 37 are examples of what he calls a theme of "compensation".[17] In this theme, Shakespeare views the Fair Youth as a divine compensation "for all his own deficiencies of talent and fortune and for all his failures and disappointments."[17] Shakespeare's faults, the troubles he has met, and the losses he has suffered, are compensated by the positive attributes and the friendship of the Fair Youth.[17]

Audio recording

- The actor, David Warner, reads this sonnet on the 2002 album When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

Notes

- ↑ Pooler 1918, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Booth 2000, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 4 Duncan-Jones 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ Kerrigan 1995, p. 89.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 Alden 1916, p. 73.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2010, pp. 160-161.

- ↑ Booth 2000.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones & 2010 p. 161.

- ↑ Wither 1635, p. 209.

- ↑ Evans & Tobin 1997, p. 1050.

- ↑ Evans & Tobin 1997, p. 1063.

- ↑ Leishman 2005, p. 110.

- ↑ Leishman 2005, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Leishman 2005, pp. 110–111.

- 1 2 3 Leishman 2005, pp. 203–204.

References

- Earl, A.J. (July 1978). "Romeo and Juliet and the Elizabethan Sonnets". English: Journal of the English Association. 27 (128–129): 99–120. doi:10.1093/english/27.128-129.99.

- Evans, G. Blakemore; Tobin, J.J.M., eds. (1997). The Riverside Shakespeare (Second ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-75490-9.

- Leishman, J.B. (2005) [first published 1961]. Themes and Variations in Shakespeare's Sonnets. Routledge Library Editions. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415612241 – via Questia.

- Pooler, Charles Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, first series. London: Methuen & Company. hdl:2027/uc1.32106001898029. OCLC 4770201. OL 7214172M.

- Wither, George (1635). A collection of emblems, ancient and moderne, quickened with metricall illustrations. London: A. M. for H. Taunton.

Further reading

- Baldwin, T.W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005120350. OCLC 2557085. OL 6072810M – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 747305284. OL 6109905M – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). "The Sonnets". In Cheney, Patrick. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 125–143. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521846277.008. ISBN 9781139001274 – via Cambridge Core. (Subscription required (help)).

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

- Text and notes (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

.png)