Social grooming

Social grooming is a behaviour in which social animals, including humans, clean or maintain one another's body or appearance. A related term, allogrooming, indicates social grooming between members of the same species. Grooming is a major social activity, and a means by which animals who live in close proximity may bond and reinforce social structures, family links, and build companionships. Social grooming is also used as a means of conflict resolution, maternal behaviour and reconciliation in some species.[1][2] Mutual grooming typically describes the act of grooming between two individuals, often as a part of social grooming, pair bonding, or a precoital activity.

Evolutionary advantages

There are a variety of proposed mechanisms by which social grooming behavior has been hypothesized to increase fitness. These evolutionary advantages may come in the form of health benefits including reduced disease transmission and reduced stress levels, maintaining social structure, and direct improvement of fitness as a measure of survival.

Health benefits

Social grooming behavior has been shown to elicit an array of health benefits in a variety of species. For example, group member connection has the potential to mitigate the potentially harmful effects of stressors. In macaques, social grooming has been proven to reduce heart rate.[3] Social affiliation during a mild stressor was shown to correlate with lower levels of mammary tumor development and longer lifespan in rats, while lack of this affiliation was demonstrated to be a major risk factor.[4] Grooming has also been shown to play an integral role in reducing tick load in wild baboons (Papio cynocephalus). These ectoparasitic ticks carry the potential to act as vectors for the spreading of disease and infection by common tick-borne parasites such as haemoprotozoan.[5] Baboons with lower tick loads show decreased occurrence of such infections and display signs of greater health status, evidenced by higher hematocrit (packed red cell volume) levels.

Reinforcing social structure and building relationships

One of the most critical functions of social grooming is to establish social networks and relationships. In many species, individuals form close social connections dubbed “friendships.”[6] In primates especially, grooming is known to have major social significance and function in the formation and maintenance of these friendships.[7] Grooming networks in black crested gibbons have been proven to contribute greater social cohesion and stability.[8] Groups of gibbons with more stable social networks formed grooming networks that were significantly more complex, while groups with low stability networks formed far fewer grooming pairs. In meerkats, social grooming has been shown to carry the role of maintaining relationships that increase fitness.[9] In this system, researchers have observed that dominant males receive more grooming while grooming others less, thereby indicating that less dominant males groom more dominant individuals to maintain relationships. In addition to primates, animals such as deer, cows, horses, vole, mice, meerkats, coati, lions, birds, bats also form social bonds through grooming behavior.[10] Social grooming is critical for vampire bats especially, since it is necessary for them to maintain food-sharing relationships in order to sustain their food regurgitation sharing behavior.[11]

Direct fitness consequences

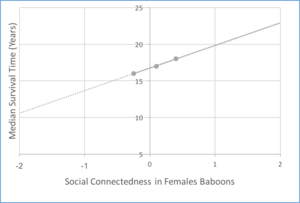

Social grooming relationships have been proven to provide direct fitness benefits to a variety of species. In particular, grooming in yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) has been studied extensively, with numerous studies showing an increase in fitness as a result of social bonds formed through social grooming behavior. One such study, which collected 16 years of behavioral data on wild baboons, highlights the effects that sociality has on infant survival.[12] A positive relationship is established between infant survival to one year and a composite sociality index, a measure of sociality based on proximity and social grooming. Evidence has also been provided for the effect of sociality on adult survival in wild baboons.[13] Direct correlations between measures of social connectedness (which focuses on social grooming) and median survival time for both female and male baboons were modeled.

Social bonds established by grooming may provide an adaptive advantage in the form of conflict resolution and protection from aggression. In wild savannah baboons, social affiliations are shown to augment fitness by increasing tolerance from more dominant group members [1] and increasing the chance of obtaining aid from conspecifics during instances of within-group contest interactions.[15] In the yellow baboon, adult females form relationships with their kin, who offer support during times of violent conflict within social groups.[16] In Barbary macaques, social grooming results in the formation of crucial relationships among partners. These social relationships serve to aid cooperation and facilitate protection against combative groups composed of other males, which can oftentimes cause physical harm.[17] Furthermore, social relationships have also been proven to decrease risk of infanticide in several primates.[18]

Altruism

Altruism, in the biological sense, refers to a behavior performed by an individual that increases the fitness of another individual while decreasing the fitness of the one performing the behavior.[19] This differs from the philosophical concept of altruism which requires the conscious intention of helping another. As a behavior, altruism is not evaluated in moral terms, but rather as a consequence of an action for reproductive fitness.[20] It is often questioned why the behavior persists if it is costly to the one performing it, however, Charles Darwin proposed group selection as the mechanism behind the clear advantages of altruism.[21]

Social grooming is considered a behavior of facultative altruism- the behavior itself is a temporary loss of direct fitness (with potential for indirect fitness gain), followed by personal reproduction.[22] This tradeoff has been compared to the Prisoner's Dilemma model, and out of this comparison came Robert Trivers reciprocal altruism theory under the title "tit-for-tat".[23] In conjunction with altruism, kin selection bears an emphasis on favoring the reproductive success of an organism's relatives, even at a cost to the organism's own survival and reproduction.[24] Because of this, kin selection is an instance of inclusive fitness, which combines the number of offspring produced with the number an individual can ensure the production of by supporting others, such as siblings.

Hamilton's Rule

Developed by W.D. Hamilton, this rule governs the idea that kin selection causes genes to increase in frequency when the genetic relatedness (r) of a recipient to an actor multiplied by the benefit to the recipient (B) is greater than the reproductive cost to the actor (C).[25] Thus, it is advantageous for an individual to partake in altruistic behaviors, such as social grooming, so long as the individual receiving the benefits of the behavior is related to the one providing the behavior.[26]

Use as a commodity

It was questioned whether some animals are instead using altruistic behaviors as a market strategy to trade for something desirable. In olive baboons, Papio anubis, it has been found that individuals perform altruistic behaviors as a form of trade in which a behavior is provided in exchange for benefits, such as reduced aggression.[27] The grooming was evenly balanced across multiple bouts rather than single bouts, suggesting that females are not constrained to complete exchanges with single transactions and use social grooming to solidify long term relationships with those in their social group.[27]

In addition, white-handed gibbons (Hylobates lar) confirmed that males were more attentive to social grooming during estrus of the females in their group.[28] Though the behavior of social grooming itself was not beneficial to the one providing the service, the opportunity to mate and subsequent fertilization increases the reproductive fitness of those participating in the behavior. This study was also successful in finding that social grooming performance cycled with that of the females ovarian cycle.[28]

Mutual grooming

Mutual grooming in ponies

Mutual grooming in ponies Three macaques grooming one another

Three macaques grooming one another Social grooming in hyacinth macaws

Social grooming in hyacinth macaws Allopreening in Yellow-billed Babbler

Allopreening in Yellow-billed Babbler Bonnet macaque allogrooming while infant suckles

Bonnet macaque allogrooming while infant suckles

Many animals groom each other in the form of stroking, scratching, and massaging. This activity often serves to remove foreign material from the body to promote the communal success of these socially active animals. There exists a wide array of socially grooming animals throughout the kingdom, including primates, insects,[29] birds,[30] and bats.[31] While thorough research has still yet to be engaged, much has been learned about social grooming in non-human animals via the study of primates. The driving force behind mammal social grooming is primarily believed to be rooted in adaptation to consolatory behavior as well as utilitarian purposes in the exchange of resources such as food, sex, and communal hygiene.[2][32][33][34]

Insects

In insects, grooming often involves the important role of removing foreign material from the body. The honey bee, for example, engages in social grooming by cleaning body parts that cannot be reached by the receiving bee. The receiving bee extends their wings perpendicular to their body while their wings, mouth parts, and antennae are cleaned in order to remove dust and pollen. This removal of dust and pollen allows for sharpening of olfactory senses in contributing to the overall well being of the group.[35]

Bats

Recent studies have determined that vampire bats engage in social grooming much more than other types of bats to promote the well-being of the group. Facing higher levels of parasitic infection, vampire bats engage in cleaning one another as well as sharing food via regurgitation. This activity prevents ongoing infection while also promoting group success.[36]

Primates

Primates provide perhaps one of the best example of mutual grooming due to the intensive research performed regarding their varying lifestyles, and the direct variation of means of social grooming across different species. Among primates, social grooming plays a significant role in animal consolation behavior whereby the primates engage in establishing and maintaining alliances through dominance hierarchies, pre-existing coalitions, and for reconciliation after conflicts. Primates groom socially in moments of boredom as well, and the act has been shown to reduce tension and stress.[37] This reduction in stress is often associated with observed periods of relaxed behavior, and primates have been known to fall asleep while receiving grooming.[38]

Grooming in primates is not only utilized for alliance formation and maintenance, but to exchange resources such as communal food, sex, and hygiene. Wild baboons have been found to utilize social grooming as an activity to remove ticks and other insects from others. In this grooming, the body areas receiving significant attention appear to be the regions where the baboons themselves cannot reach. Grooming activity in these regions is used to remove parasites, dirt, dead skin, as well as tangled fur to help keep the animal’s health in good condition despite an individual inability to reach and clean certain areas.[39]

Recent studies regarding chimpanzees have determined the direct correlation of the release of oxytocin to consolatory behavior.[40] This behavior as well as release has been noted in primates such as the Vervet monkey, a primate species that actively engages in social grooming from early childhood to adulthood. Vervet monkey siblings often have conflict over grooming allocation by their mother, yet, grooming remains an activity that mediates tension and is low cost for alliance formation and maintenance. This grooming occurs both between the siblings as well as involving the mother.[41]

Recent studies regarding the crab-eating macaques have shown that males will groom females in order to procure sex. One study found that a female has a greater likelihood to engage in sexual activity with a male if he had recently groomed her, compared to males who had not groomed her.[41]

Birds

In 2010, researchers determined the existence of a form of social grooming as a consolation behavior within ravens via a form of bystander contact, whereby observer ravens would act to console a distressed victim via contact sitting, preening, as well as beak-to-beak touching.[42]

Horses

Horses engage in mutual grooming via the formation of 'pair bonds' where parasites and other contaminants on the surface of the body are actively removed. This removal of foreign material is primarily performed in hard-to-reach areas such as the neck via nibbling.[43]

Cattle

Allogrooming is a behaviour commonly seen in many types of cattle, including dairy and beef breeds. The act of social licking can be seen specifically in heifers to initiate social dominance, emphasize companionship and improve hygiene of oneself or others. This behaviour seen in cows may provide advantages including reduced parasite loads, social tension and competition at the feed bunk.[44] It is understood that social licking can provide long term benefits such as promoting positive emotions and a relaxed environment.[45]

Endocrine effects

Social grooming has shown to be correlated with changes in endocrine levels within individuals. Specifically, there is a large correlation between the brain's release of oxytocin and social grooming. Oxytocin is hypothesized to promote prosocial behaviours due to its positive emotional response when released.[46] Further, social grooming also releases beta-endorphins which promote physiological responses in stress reduction. These responses can occur from the production of hormones and endorphins, or through the growth or reduction in nerve structures. For example, in studies of suckling rats, rats who received warmth and touch when feeding had lower blood pressure levels than rats who did not receive any touch. This was found to be a result of an increased vagal nerve tone, meaning they had had higher parasympathetic nervous response and lower sympathetic nervous response to stimulus, resulting in a lower stress response.[47] Social grooming is a form of innocuous sensory activation. Innocuous sensory activation, characterized by non aggressive contact, stimulates an entirely separate neural pathway from nocuous aggressive sensory activation.[48] Innocuous sensations are transmitted through the dorsal column-medial lemniscal system.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a peptide hormone known to help express social emotions such as altruism, which in turn provides a positive feedback mechanism for social behaviours.[46] For example, studies in vampire bats have shown that intranasal injections of oxytocin have increased the amount of allogrooming done by female bats.[31] The release of oxytocin, found to be stimulated by positive touch( such as allogrooming), positive smells and sounds, can have physiological benefits to the individual. Benefits can include: relaxation, healing, and digestion stimulation.[49] Further, reproductive benefits have been found such as studies in rats have shown that the release of oxytocin can increase male reproductive success. The role of oxytocin is important in maternal pair bonding, and is hypothesized to promote similar bonding in social groups as a result of positive feedback loops from social interactions.[50]

Beta-endorphins

Grooming stimulates the release of beta-endorphin, which is one physiological reason for why grooming appears to be relaxing.[51] Beta-endorphins are found in neurons in the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. Beta-endorphins are found to be opioid agonists. Opioids are molecules that act on receptors to promote feelings of relaxation, and reduce pain.[52] A study in monkeys shows the changes in opiate expression in the body, mirroring changes in beta-endorphin levels, influences desire for social grooming. In using opiate receptor blockades, which decrease the level of beta-endorphins, the monkeys responded with an increased desire to be groomed. In contrast, when the monkeys were given morphine, the desire to be groomed dropped significantly.[53] Beta- endorphins have been difficult to measure in animal species, differently from oxytocin which can be measured by sampling cerebrospinal fluid, and therefore have not been linked as strongly with social behaviours.[50]

Glucocorticoids receptors

Glucocorticoids are steroid hormones that are synthesized in the adrenal cortex and are a part of the group of corticosteroids. Glucocorticoids are involved in immune function, and are a part of the feedback system that reduces inflammation.[54] Further, glucocorticoids are involved in glucose metabolism. Studies in macaques have shown that increased social stress results in glucocorticoid resistance, further inhibiting immune function.[55] Macaques who participated in social grooming showed decreased levels of viral load, which points toward decreased levels of social stress resulting in increased immune function and glucocorticoid sensitivity. Additionally, an article published in 1997 concluded that an increase in maternal grooming resulted in a proportionate increase in Glucocorticoid receptors on target tissue in the neonatal rat.[56] In the study on neonatal rats, it was found that the receptor number was altered because of a change in both serotonin and thyroid-stimulating hormone concentrations. An increase in the number of receptors might influence the amount of negative feedback on corticosteroid secretion and prevent the undesirable side effects of an abnormal physiologic stress response.[57] Social grooming can change the number of glucocorticoid receptors, which can result in increased immune function.

Studies have also shown that male baboons who participate more in social grooming show lower basal cortisol concentrations.[58]

See also

| Look up social grooming in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Social grooming. |

References

- 1 2 Henazi, Peter S.; Barrett, Louise (1999-01-01). "The value of grooming to female primates". Primates. 40 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1007/BF02557701. ISSN 0032-8332.

- 1 2 Aureli, F.; van Schaik, C.; van Hooff, J (1989). "Functional aspects of reconciliation among captive long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis)". American Journal of Primatology. 19: 39–51. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350190105.

- ↑ Aureli, Filippo; Waal, Frans B. M. (2000-01-01). Natural Conflict Resolution. University of California Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN 9780520223462.

- ↑ Yee, Jason R.; Cavigelli, Sonia A.; Delgado, Bertha; McClintock, Martha K. "Reciprocal Affiliation Among Adolescent Rats During a Mild Group Stressor Predicts Mammary Tumors and Lifespan". Psychosomatic Medicine. 70 (9): 1050–1059. doi:10.1097/psy.0b013e31818425fb.

- ↑ Akinyi, Mercy Y.; Tung, Jenny; Jeneby, Maamun; Patel, Nilesh B.; Altmann, Jeanne; Alberts, Susan C. (2013-03-01). "Role of grooming in reducing tick load in wild baboons (Papio cynocephalus)". Animal Behaviour. 85 (3): 559–568. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.12.012. PMC 3961061. PMID 24659824.

- ↑ Seyfarth, Robert M.; Cheney, Dorothy L. (July 5, 2011). "The Evolutionary Origins of Friendship". Annual Review of Psychology. 63: 153–177. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100337.

- ↑ Schino, Gabriele (2001-08-01). "Grooming, competition and social rank among female primates: a meta-analysis". Animal Behaviour. 62 (2): 265–271. doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1750.

- ↑ Guan, Zhen-Hua; Huang, Bei; Ning, Wen-He; Ni, Qing-Yong; Sun, Guo-Zheng; Jiang, Xue-Long (2013-12-01). "Significance of grooming behavior in two polygynous groups of western black crested gibbons: Implications for understanding social relationships among immigrant and resident group members". American Journal of Primatology. 75 (12): 1165–1173. doi:10.1002/ajp.22178. ISSN 1098-2345.

- ↑ Kutsukake, Nobuyuki; Clutton-Brock, Tim H. (2010-02-01). "Grooming and the value of social relationships in cooperatively breeding meerkats". Animal Behaviour. 79 (2): 271–279. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.10.014.

- ↑ Carter, Gerald; Leffer, Lauren (2015-10-07). "Social Grooming in Bats: Are Vampire Bats Exceptional?". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138430. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138430. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4596566. PMID 26445502.

- ↑ Carter, Gerald; Leffer, Lauren (2015-10-07). "Social Grooming in Bats: Are Vampire Bats Exceptional?". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138430. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138430. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4596566. PMID 26445502.

- ↑ Silk, Joan B.; Alberts, Susan C.; Altmann, Jeanne (2003-11-14). "Social Bonds of Female Baboons Enhance Infant Survival". Science. 302 (5648): 1231–1234. doi:10.1126/science.1088580. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 14615543.

- ↑ Archie, Elizabeth A.; Tung, Jenny; Clark, Michael; Altmann, Jeanne; Alberts, Susan C. (2014-10-22). "Social affiliation matters: both same-sex and opposite-sex relationships predict survival in wild female baboons". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1793): 20141261. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1261. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4173677. PMID 25209936.

- ↑ Archie, Elizabeth A.; Tung, Jenny; Clark, Michael; Altmann, Jeanne; Alberts, Susan C. (2014-10-22). "Social affiliation matters: both same-sex and opposite-sex relationships predict survival in wild female baboons". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1793): 20141261. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1261. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4173677. PMID 25209936.

- ↑ Sterck, Elisabeth H. M.; Watts, David P.; Schaik, Carel P. van (1997-11-01). "The evolution of female social relationships in nonhuman primates". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 41 (5): 291–309. doi:10.1007/s002650050390. ISSN 0340-5443.

- ↑ Silk, Joan B; Alberts, Susan C; Altmann, Jeanne (2004-03-01). "Patterns of coalition formation by adult female baboons in Amboseli, Kenya". Animal Behaviour. 67 (3): 573–582. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.07.001.

- ↑ Berghänel, Andreas; Ostner, Julia; Schröder, Uta; Schülke, Oliver. "Social bonds predict future cooperation in male Barbary macaques, Macaca sylvanus". Animal Behaviour. 81 (6): 1109–1116. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.02.009.

- ↑ Schaik, Carel P. Van; Kappeler, Peter M. (1997-11-22). "Infanticide risk and the evolution of male–female association in primates". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 264 (1388): 1687–1694. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0234. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1688726. PMID 9404030.

- ↑ Graham., Bell, (2008-01-01). Selection : the mechanism of evolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198569726. OCLC 781154368.

- ↑ Okasha, Samir (2013-01-01). Zalta, Edward N., ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2013 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.2092.

- ↑ Trivers, Robert L. (1971-03-01). "The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 46 (1): 35–57. doi:10.1086/406755. ISSN 0033-5770.

- ↑ Axelrod, R.; Hamilton, W. D. (1981-03-27). "The evolution of cooperation". Science. 211 (4489): 1390–1396. doi:10.1126/science.7466396. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 7466396.

- ↑ "Origin of Species : Chapter VIII. Instinct : Objections to the theory of natural selection as applied to instincts: neuter and sterile insects by Charles Darwin @ Classic Reader". www.classicreader.com. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ↑ Wright, Sewall (1922-07-01). "Coefficients of Inbreeding and Relationship". The American Naturalist. 56 (645): 330–338. doi:10.1086/279872. ISSN 0003-0147.

- ↑ ), Smith, John Maynard, (1920- (1996-01-01). Evolutionary genetics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198542151. OCLC 954574132.

- 1 2 Frank, Rebecca (January 2009). "Impatient traders or contingent reciprocators? Evidence for the extended time-course of grooming exchanges in baboons" (PDF). Behavior. 146: 1123–1135. doi:10.1163/156853909x406455 – via Brill.

- 1 2 Barelli, Claudia; Reichard, Ulrich H.; Mundry, Roger (2011-10-01). "Is grooming used as a commodity in wild white-handed gibbons, Hylobates lar?". Animal Behaviour. 82 (4): 801–809. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.07.012.

- ↑ Moore, D.; Angel, J.E.; Cheeseman, I.M.; Robinson, G.E.; Fahrbach, S.E. (1995), "A highly specialized social grooming honey bee(Hymenoptera: Apidae)", Journal of Insect Behavior, 8 (6): 855–861, doi:10.1007/BF02009512

- ↑ Spruijt, B.M.; Van Hooff, J.A.; Gispen, W.H. (1992), "Ethology and neurobiology of grooming behavior", Physiological Reviews, 72 (3): 825–852, PMID 1320764

- 1 2 Wilkinson, G.S. (1986), "Social grooming in the common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus" (PDF), Animal Behaviour, 34 (6): 1880–1889, doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80274-3

- ↑ Lawick-Goodall, J. van (1968). "The behavior of free living chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs. 1: 161–311. doi:10.1016/s0066-1856(68)80003-2.

- ↑ de Waal, F. (1989). Peacemaking among primates. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Smuts, B., Cheney, D., Seyfarth, R., Wrangham, R., & Struhsaker, T. (1987). Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Moore, D.; Angel, J. E.; Cheeseman, I. M.; Robinson, G. E.; Fahrbach, S. E. (1995). "A highly specialized social grooming honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 8 (6): 855–861. doi:10.1007/BF02009512.

- ↑ Carter G.; Leffer L. (2015), Social Grooming in Bats: Are Vampire Bats Exceptional?. PLOS ONE 10(10): e0138430. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138430

- ↑ Schino, G.; Scucchi, S.; Maestripieri, D.; Turillazzi, P.G. (1988), "Allogrooming as a tension-reduction mechanism: a behavioral approach", American Journal of Primatology, 16: 43–50, doi:10.1002/ajp.1350160106

- ↑ Smuts, Barbara (1985), Sex and Friendship in Baboons, New York: Aldine Publications, ISBN 978-0-202-02027-3, retrieved 28 April 2010

- ↑ Smuts, Barbara B. Sex & friendship in baboons. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction, 2009. Print.

- ↑ Lawick-Goodall, J. van (1968). "The behavior of free living chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs. 1: 161–311. doi:10.1016/s0066-1856(68)80003-2.

- ↑ de Waal, F. (1989). Peacemaking among primates. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- ↑ Orlaith, N.F.; Bugnyar, T. (2010). "Do Ravens Show Consolation? Responses to Distressed Others". PLoS ONE. 5: e10605. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010605. PMC 2868892. PMID 20485685.

- ↑ Feh, C., De Mazieres, J. Grooming at a preferred site reduces heart rate in horses. Anim. Behav. 1993;46:1191–1194.

- ↑ Val-Laillet, David; Guesdon, Vanessa; Keyserlingk, Marina A.G. von; Passillé, Anne Marie de; Rushen, Jeffrey. "Allogrooming in cattle: Relationships between social preferences, feeding displacements and social dominance". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 116 (2–4): 141–149. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2008.08.005.

- ↑ Laister, Simone; Stockinger, Barbara; Regner, Anna-Maria; Zenger, Karin; Knierim, Ute; Winckler, Christoph. "Social licking in dairy cattle—Effects on heart rate in performers and receivers". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 130 (3–4): 81–90. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2010.12.003.

- 1 2 Kemp, Andrew H.; Guastella, Adam J. (2011-08-08). "The Role of Oxytocin in Human Affect". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 20 (4): 222–231. doi:10.1177/0963721411417547.

- ↑ "OXYTOCIN MAY MEDIATE THE BENEFITS OF POSITIVE SOCIAL INTERACTION AND EMOTIONS". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 23: 819–835. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00056-0. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ↑ Uvnäs-Moberg, Kerstin (1997-01-01). "Physiological and Endocrine Effects of Social Contact". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 807 (1): 146–163. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51917.x. ISSN 1749-6632.

- ↑ Uvnäs-Moberg, Kerstin (1998-11-01). "OXYTOCIN MAY MEDIATE THE BENEFITS OF POSITIVE SOCIAL INTERACTION AND EMOTIONS1". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 23 (8): 819–835. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00056-0.

- 1 2 Dunbar, R. I. M. (2010-02-01). "The social role of touch in humans and primates: Behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Touch, Temperature, Pain/Itch and Pleasure. 34 (2): 260–268. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.001.

- ↑ Keverne, E.B.; Martensz, N.D.; Tuite, B. (1989), "Beta-endorphin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of monkeys are influenced by grooming relationships", Psychoneuroendocrinology, 14 (1–2): 155–161, doi:10.1016/0306-4530(89)90065-6, PMID 2525263

- ↑ FRCA., Hemmings, Hugh C., MD, PhD, (2013-01-01). Physiology and Pharmacology for Anesthesia: Foundations and Clinical Application: Expert Consult - Online and Print. Elsevier. ISBN 1437716792. OCLC 830351627.

- ↑ Keverne, Eric B.; Martensz, Nicholas D.; Tuite, Bernadette (1989-01-01). "Beta-endorphin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of monkeys are influenced by grooming relationships". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 14 (1–2): 155–161. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(89)90065-6. PMID 2525263.

- ↑ Sapolsky, Robert M.; Romero, L. Michael; Munck, Allan U. (2000-02-01). "How Do Glucocorticoids Influence Stress Responses? Integrating Permissive, Suppressive, Stimulatory, and Preparative Actions". Endocrine Reviews. 21 (1): 55–89. doi:10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. ISSN 0163-769X.

- ↑ Capitanio, John P.; Mendoza, Sally P.; Lerche, Nicholas W.; Mason, William A. (1998-04-14). "Social stress results in altered glucocorticoid regulation and shorter survival in simian acquired immune deficiency syndrome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (8): 4714–4719. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.8.4714. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 22556. PMID 9539804.

- ↑ Liu, Dong; Diorio, Josie; Tannenbaum, Beth; Caldji, Christian; Francis, Darlene; Freedman, Alison; Sharma, Shakti; Pearson, Deborah; Plotsky, Paul M. (1997-09-12). "Maternal Care, Hippocampal Glucocorticoid Receptors, and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Responses to Stress". Science. 277 (5332): 1659–1662. doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1659. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9287218.

- ↑ Sapolsky, Robert M. (September 1997), "The Importance of a Well-Groomed Child", Science, 277 (5332): 1620–1621, doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1620, PMID 9312858

- ↑ Ray, Justina C.; Sapolsky, Robert M. (1992-01-01). "Styles of male social behavior and their endocrine correlates among high-ranking wild baboons". American Journal of Primatology. 28 (4): 231–250. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350280402. ISSN 1098-2345.

Further reading

- Aureli, F., van Schaik, C., & van Hooff, J (1989). "Functional aspects of reconciliation among captive long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis)". American Journal of Primatology. 19: 39–51. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350190105.

- Lawick-Goodall, J. van. (1968). "The behavior of free living chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs. 1: 161–311. doi:10.1016/S0066-1856(68)80003-2.

- de Waal, F. (1989). Peacemaking among Primates. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Smuts, B., Cheney, D., Seyfarth, R., Wrangham, R., & Struhsaker, T. (1987). Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226767161.

- Schino, G.; Scucchi, S.; Maestripieri, D.; Turillazzi, P.G. (1988). "Allogrooming as a tension-reduction mechanism: a behavioral approach". American Journal of Primatology. 16: 43–50. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350160106.

- Smuts, Barbara (1985). Sex and Friendship in Baboons. New York: Aldine Publications. ISBN 978-0-202-02027-3. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Gumert, Michael D. (December 2007). "Payment for sex in a macaque mating market" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 74 (6): 1655–1667. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.03.009.

- Lee, P.C. (1987). "Sibships: Cooperation and Competition Among Immature Vervet Monkeys". Primates. 28 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1007/BF02382182.

- Moore, D.; Angel, J.E.; Cheeseman, I.M.; Robinson, G.E.; Fahrbach, S.E. (1995). "A highly specialized social grooming honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 8 (6): 855–861. doi:10.1007/BF02009512.

- Spruijt, B.M.; Van Hooff, J.A.; Gispen, W.H. (1992). "Ethology and neurobiology of grooming behavior". Physiological Reviews. 72 (3): 825–852. PMID 1320764.

- Kimura, R. (1998). "Mutual grooming and preferred associate relationships in a band of free-ranging horses". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 59 (4): 265–276. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00129-9.

- Wilkinson, G.S. (1986). "Social grooming in the common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 34 (6): 1880–1889. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80274-3.

- Keverne, E.B.; Martensz, N.D.; Tuite, B. (1989). "Beta-endorphin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of monkeys are influenced by grooming relationships". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 14 (1–2): 155–161. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(89)90065-6. PMID 2525263.

- Sapolsky, Robert M. (September 1997). "The Importance of a Well-Groomed Child". Science. 277 (5332): 1620–1621. doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1620. PMID 9312858.

- Vrontou, S.; Wong, A. M.; Rau, K. K.; Koerber, R.; Anderson, D. J. (2013). "Genetic identification of C fibres that detect massage-like stroking of hairy skin in vivo". Nature. 493 (7434): 669–673. doi:10.1038/nature11810. PMC 3563425. PMID 23364746.