Slingsby T67 Firefly

| RF-6, T67 Firefly | |

|---|---|

| Slingsby T67M260 Firefly | |

| Role | Trainer/tourer/sport aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Fournier, Slingsby Aviation |

| First flight | 12 March 1974 |

| Retired | United States Air Force 2006 |

| Status | Limited Service |

| Primary users | Royal Jordanian Air Force Belize Defence Force Air Wing Bahrain Air Force |

| Produced | 1974-1995 |

| Number built | > 250 |

| Developed into | Sportavia RS-180 |

The Slingsby T67 Firefly, originally produced as the Fournier RF-6, is a two-seat aerobatic training aircraft, built by Slingsby Aviation in Kirkbymoorside, Yorkshire, England.[1] It has been successfully used by the UK armed forces, where the Royal Air Force used 22 Slingsby T67M260s as their basic trainer between 1995 and 2010, with over 100,000 flight hours flown out of RAF Barkston Heath (Army, Royal Navy and Royal Marines students, who lived on camp at RAF Cranwell) and also RAF Church Fenton (RAF and foreign students were accommodated at RAF Linton on Ouse, and bussed to and from the airfield daily). The Slingsby has also been used by the Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force, the Royal Jordanian Air Force (still currently used), and other military training schools around the world for many years. Also, in December 2012, the National Flying Laboratory Centre at Cranfield University in the UK acquired a T67M260 to supplement its Scottish Aviation Bulldog aerobatic trainer for MSc student flight experience and training.

The Slingsby is a very competent basic trainer and is still operated by many private individuals for standard-level aerobatics training. It was flown by HRH Prince Harry as a basic trainer during his Army Air Corps flying training course, based at RAF Barkston Heath, including his first solo flight in Slingsby T67M260 registration G-BWXG in 2009.[2] Tom Cassells a British Aerobatic Champion regularly flies his Slingsby Firefly. However, in the mid-1990s, the aircraft became controversial in the United States after three fatal accidents during US Air Force training operations, although an Air Force investigation eventually attributed the accidents primarily to pilot error.

Development

The RF-6 was designed by René Fournier, and first flew on 12 March 1974. An all-wooden construction, it featured a high aspect-ratio wing echoing his earlier motorglider designs. Fournier set up his own factory at Nitray to manufacture the design, but after only around 40 had been built, the exercise proved financially unviable, and he was forced to close down production. A four-seat version was under development by Sportavia as the RF-6C, but this demonstrated serious stability problems that eventually led to an almost complete redesign as the Sportavia RS-180.

In 1981, Fournier sold the development rights of the RF-6B to Slingsby, which renamed it the T67. The earliest examples, the T67A, were virtually identical to the Fournier-built aircraft, but the design was soon revised to replace the wooden structure with one of composite material. Slingsby produced several versions developing the airframe and adding progressively larger engines. The Slingsby T67M, aimed at the military (hence "M") training market, was the first to include a constant-speed propeller and inverted fuel and oil systems. Over 250 aircraft have been built, mainly the T67M260 and closely related T-3A variants. Although operated successfully in the United Kingdom and Canada, the program would end in the United States because of a fatal crash following an engine failure. The type was meant to not only replace the Cessna T-41 introductory trainer, but also to meet the Enhanced Flight Screening Program (EFSP) requirements. The US Air Force has no replacement for this type, as it no longer provides training to non-fliers. The aircraft were eventually declared in excess of need in the early 2000s (decade) and disposed of by scrapping in 2006.

Operational history

The largest Firefly operator was the United States Air Force, where it was given the designation T-3A Firefly. The Firefly was selected in 1992 to replace the T-41 aircraft for the command's Enhanced Flight Screening Program, which would include aerobatic maneuvers. From 1993 to 1995, 113 aircraft were purchased and delivered to Hondo Municipal Airport, Texas, and the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado.

The Commander of the Air Education and Training Command stood down the entire T-3A fleet in July 1997 as a result of uncommanded engine stoppages during flight and ground operations. A major factor driving the decision were the three T-3A Class A mishaps. Three Air Force Academy cadets and three instructors were killed in these T-3A mishaps. The Air Force Accident Investigation Board report summary attributed the three fatal accidents to:

i. 22 February 1995: The instructor pilot (IP) failed to apply antispin rudder as directed in flight manual. The IP’s spin academic instruction, flying training, and error analysis experience did not adequately prepare him to recognize his improper rudder application.

ii. 30 September 1996: During a simulated forced landing, the engine quit for some unknown reason. After the engine quit, the aircraft entered a stall from which the IP was unable to recover prior to ground impact.

iii. 25 June 1997: The aircraft departed controlled flight for an unknown reason during the turn to downwind. The IP’s failure to recognize this departure and take immediate positive corrective action was the primary cause of the accident. (The AIB President found no clear and convincing evidence of mechanical failure.)

In April 1995 a 3rd Flying Training Squadron lost a T-3A in a landing accident. During a planned student no-flap landing at Hondo Airfield, Hondo, Texas USA. At touchdown the student jerked the aircraft back into the air and the plane stalled. The instructor took the aircraft and applied full throttle but he couldn't prevent the crash. The aircraft touched down beside the runway and the nose gear struck the lip of a cross runway and collapsed causing loss of control and heavy damage. The only injury was a slight injury to the instructor's foot from the nose gear coming up through the cockpit floor. The mishap was classified as a Class B (non-hull loss) because it was said the aircraft could be repaired for less than $300,000 even though the Air Force chose to scrap the plane.

The planes had been purchased for $32 million, and following the third accident, $10 million was spent on fixes to make them airworthy after grounding. "The Air Force found the cost of getting the aircraft or any of the aircraft's components in airworthy condition for resale was prohibitive" and "In September 1999, the chief of staff of the Air Force approved termination of the T-3A EFSP, and AETC declared all T-3A aircraft excess to the command's needs." In 2000, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force requested a new mission be found for the T-3A; however, a study completed in 2002 did not recommend a follow-on mission.[3] "The remaining T-3A aircraft were then stored without maintenance at the Air Force Academy and the Hondo Airport. In the 2002 to 2003 timeframe, the 53 aircraft at the Air Force Academy were disassembled, crated and trucked to Hondo." On 9 September 2006, it was announced the remaining 53 (114 were originally purchased) disassembled T-3 aircraft, which had been declared in excess need for over six years, were scrapped.[4] Edwards Air Force Base operated a single T67M Slingsby for test pilot training which originated from the fuel system flight tests in 1998 until it crashed in 2014 killing both occupants [https://www.ntsb.gov/_layouts/ntsb.aviation/brief.aspx?ev_id=20141024X52246&key=1]. Although the Air Force terminated the EFSP, it now uses the non-aerobatic Diamond DA20 for Initial Flight Screening through the third-party Doss Aviation.

Variants

- RF-6B

- Main Fournier production series with Rolls-Royce-built Continental O-200 100 hp (75 kW) engine (43 built)

- RF-6B/120

- RF-6B with Lycoming O-235 120 hp (89 kW) engine, one built

- RF-6C

- Four-seat version of RF-6B built by Sportavia with Lycoming O-320 engine, four built, developed into Sportavia RS-180

- T67A

- Slingsby-built RF-6B/120 certified on 1 October 1981, O-235 118hp engine, wooden construction, 2 blade fixed prop, fuel in firewall tank, single piece canopy, ten built

- T67M Firefly

- First flown on 5 December 1982 and certified on 2 August 1983, the T67M was developed from the T67A as a glass-reinforced plastic aircraft for a role as a military trainer. The T67M has a 160 hp (120 kW) fuel-injected Lycoming AEIO320-D1B and a two-blade Hoffman HO-V72L-V/180CB constant-speed propellor, single piece canopy, fuel in firewall tank. The fuel-injected engine with inverted fuel and oil systems allowed the aircraft to perform sustained negative-G (inverted) aerobatics, although inverted spins were never formally approved. A total of 32 T67Ms (including the later T67M MkII) were produced.

- T67B

- First flown on 16 April 1981 and certified on 18 September 1984, the T67B was effectively the T67A made, like the T67M, in glassfibre reinforced plastic, but without the up-rated engine and propeller. O-235 118hp engine, 2 blade fixed prop, fuel in firewall tank, single piece canopy. A total of 14 T67Bs were produced.

- T67M MkII Firefly

- Certified on 20 December 1985, AEIO-320 fuel injected 160hp engine, 2 blade constant speed prop, inverted fuel and oil systems. The T67M MkII replaced the single-piece canopy of the T67M with a two-piece design, and the single fuselage fuel tank with two, larger tanks in the wings.

- T67M200 Firefly

- Certified on 19 June 1987, the T67M200 was had a more powerful 200 hp (149 kW) Lycoming AEIO360-A1E with a three-bladed Hoffman propellor, inverted fuel and oil systems. A total of 26 T67M-200s were produced.

- T67C Firefly

- Certified on 15 December 1987, the T67C was the last of the "civilian" variants, based on the T67B with an uprated 160 hp (120 kW) Lycoming O-320 engine, but without fuel injection and inverted-flight systems found on the T67M variants. Two blade constant speed prop. Two further sub-versions of the T67C copied the two-piece canopy (T67C-2) and wing tanks (T67C-3, sometimes known as the T67D) from the T67M MkII. A total of 28 T67Cs were produced across the three versions.

- T67M260 Firefly

- Certified on 11 November 1993, the T67M260 added even more power from the six-cylinder, 260 hp (190 kW) Lycoming AEIO540-D4A5 engine, three blade constant speed prop. Unusually for side-by-side light aircraft, the T67M260 was built to be flown solo from the right-hand seat to allow student pilots to immediately get used to the left-hand throttle found in most military aircraft - earlier models of the T67M had a second throttle on the left-hand sidewall of the cabin. A total of 51 T67M-260s were produced. They were used to successfully train hundreds of RAF, RN, British Army, and foreign and Commonwealth pilots through Joint Elementary Flying Training School until late 2010.

- T67M260-T3A Firefly

- Certified on 15 December 1993, the last military version of the T67 family was the T67M260-T3A, of which the entire production run of 114 was purchased by the United States Air Force, where it was known as the T-3A. The T-3A was basically the T67M260 with the addition of air conditioning. Although the US media claimed the aircraft was to blame after four aircraft were destroyed in accidents, no engine stoppages or vapour-lock problems with the fuel system were found during very thorough tests at Edwards AFB. All three instructors killed in the accidents came from the C-141, a large-transport aircraft. Their only prior aerobatic experience was in Air Force pilot training in the T-37 and T-38 jet trainers. This, combined with thinner air at the higher density altitude of the Academy airfield and training areas, meant spin recovery was delayed and/or improper spin prevent/recovery techniques were used. Parachutes were not worn on the first fatal accident but were worn on the second and third fatal accidents. Both of these accidents were caused by low altitude spins. Following the three fatal accidents and an engine failure in the Academy landing pattern the fleet was grounded in 1997 and stored without maintenance until being destroyed in 2006.

- CT-111 Firefly

- Designation by the Canadian Forces internally only as aircraft are registered as civilian aircraft

Operators

Military operators

- Bahrain Air Force operates three T67M-260[5]

- Belize Defence Force Air Wing - 1 x T67M-260[5]

- Royal Jordanian Air Force- 14 × T67M-260[5]

The Firefly is used by the Royal Netherlands Air Force during pilot selection which is contracted out to TTC at Seppe Airport.

Former military operators

The Firefly was used as a basic military training aircraft in Canada. The Canadian Fireflies entered service in 1992 replacing the CT 134 Musketeer. They were, in turn, replaced in 2006 by the German-made Grob G-120 when the contract ended. The aircraft were owned and operated by Bombardier Aerospace under contract to the Canadian Forces. Unlike the United States, there were no serious operational or maintenance issues with the Fireflies in Canadian military service.

The Firefly was used as a basic military trainer in the United Kingdom until spring 2010, when they were replaced by Grob Tutor aircraft. The aircraft are owned and operated under contract by a civilian company on behalf of the military. In the UK, it was under a scheme known as "Contractor Owned Contractor Operated" (CoCo).

Civil operators

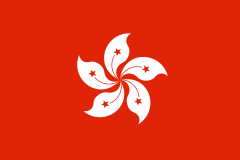

.svg.png)

- Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force/Hong Kong Government Flying Service - retired all four T-67M-200 aircraft after 1996

- Hong Kong Aviation Club - used for pilot aerobatics training

- Auckland Aero Club - one T67B - used for pilot aerobatics training and high-visibility scenic flight.[6]

- North Shore Aero Club - one T67M200 - Used for pilot aerobatics training.[7]

- FTEJerez - one T67M MarkII - used to provide upset training to graduates [8]

- Turkish Aeronautical Association (Türk Hava Kurumu) - used to give basic flight training to ATPL trainees (T67M200)

- Swift Aircraft purchased 21 Slingsby T.67M260 Aircraft from Babcock Defense Services in June 2011, to be offered for sale or lease.[9]

- Cranfield University operates one T67 to provide flight initiations for aerospace engineers.

Accidents

Fatal Crash January 1984: British T67M from Specialist Flying Training Ltd, destroyed aircraft with one fatality, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Crash August 1985: British T67A from Specialist Flying Training Ltd, destroyed aircraft with no fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash May 1986: British T67M from Slingsby Aviation, destroyed aircraft with one fatality, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Crash February 1987: British T67A from Slingsby Aviation, destroyed aircraft with no fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash March 1987: British T67A from Specialist Flying Training Ltd, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash June 1987: British T67A from Specialist Flying Training Ltd, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash September 1987: Swiss T67M from Groupe de vol á moteur du Chablais, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6.

Fatal Crash November 1988: British T67C from Slingsby Aviation Ltd, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Crash June 1989: British T67C from Specialist Flying Training Ltd, destroyed aircraft with no fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash February 1995: US Air Force Academy T-3A failed to recover from a practice spin. Both instructor and student were fatally injured.

Destroyed Aircraft April 1995: Hondo Texas T-3A crashed on landing. The instructor pilot suffered a minor injury, the student pilot was uninjured. The Air Force did not consider this accident to be a Class A mishap (hull loss) because they determined the aircraft could be repaired for less than $300,000 even though they chose to scrap the airplane.

Crash July 1995: British T67M from Hunting Aircraft Ltd, destroyed aircraft with no fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Crash May 1996: British T67M200 from Firefly Aerial Promotions Ltd, destroyed aircraft with one fatality, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash September 1996: US Air Force Academy T-3A Lycoming engine failure / stall / spin / crash. Both instructor and student were fatally injured.

Fatal Crash June 1997: US Air Force Academy T-3A entered an unintentional spin / crash from the Academy Airfield downwind. Both instructor and student were fatally injured. This is a classic loss of control pilot error accident.

Crash July 1997: British T67M200 from Mark Bristow Smithson t/a Sport to Business, destroyed aircraft with no fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash October 1988: British T67C from Slingsby Aviation PLC, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash November 2002: British T67B owned by Richard Laurence Brinklow, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash May 2005: British T67C owned by Open Skies Partnership, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Crash Feb 2006: British T67B owned by The Pathfinder Flying Club Ltd, destroyed aircraft with no fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash July 2006: British T67M flown by Nicholas James Heard & Stephen John Cowham, destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash August 2006: Jordanian T67M260 flown by Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF), destroyed aircraft with one fatality, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash June 2009: Jordanian T67M260 flown by Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF), destroyed aircraft with one fatality, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash November 2011: Turkish T67M200 flown by Türk Hava Kurumu (THK), destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash May 2013: Jordanian T67A flown by Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF), destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash October 2014: Edwards AFB test pilot school aircraft crashed killing both pilots during spin training. The flight training at Edwards AFB did not include following the spin recovery as published in the official Slingsby flight manual - the US military wrote their own manual for this aircraft.

Fatal Crash April 2015: Jordanian T67M260 flown by Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF), destroyed aircraft with two fatalities, ref: https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/dblist.php?AcType=RF6

Fatal Crash April 2016: Civilian T67 an eye witness said the aircraft stalled and entered a spin then crashed while doing aerobatics. Both pilots died, they were trainee RAF Pilots flying a recreational sortie. This was not during military training, the pilots had only just begun military flight training and had elected to hire a similar T67 aircraft to "do a display" over a relatives house at low level without being qualified for low-level flight.

The 1998 Enhanced Flight Screening Program Broad Area Review report on page 23 lists eight more fatal T67 crashes not listed in the Aviation Safety Network list shown above. They include:

1984 UK Aerobatics - Aerial display, insufficient altitude for maneuver

1984 UK Cross Country - On training flight, pilot became lost and attempted a bail-out too low

1985 UK Spin - Failed to recover, no pre-impact defects

1987 Sweden Aerobatics - Low level aerobatics

1989 Japan Aerobatics - Steep turn after takeoff, rolled inverted (stall)

1989 Turkey Simulated Forced Landing - Wing dropped near the ground (stall). This is very similar to the Academy's second fatal T-3 accident.

1989 Turkey Formation - On inside of turn after takeoff, hit house

1990 New Zealand Aerobatics - No information

These accidents from the Broad Area Review included 12 fatalities. Adding these eight accidents to the Aviation Safety Network's total of 28 destroyed aircraft and we have a grand total of 36 T67's destroyed with 48 fatalities in flying accidents--that's 14% of the T67 fleet that has been destroyed in accidents.

There are two reasons why the T67 has a higher than average accident rate - Firstly the use to which the aircraft is put - Nearly all the aircraft were sold as military trainers which mandates aerobatic training and later the aircraft was used as a aerobatic training aircraft by private operators - The T67 is almost never used for conventional flight training in a straight line. The second reason is the failure of the training organisations to follow the published spin recovery technique in the flight manual. It is worth noting that in one accident where the pilots bailed out in the spin, they were questioned afterwards and the pilot stated he was not aware of the published spin recovery procedure in the flight manual at all and could "not understand" why the aircraft failed to recover doing what he "normally did".

First reason - Use to which the aircraft has been put - Primarily Military Training and Aerobatics including flying low-level at air shows. Ab Initio (meaning starting out flying from no experience) military training involves spin recovery training and aerobatics. Whereas normal private flight training that other aircraft are involved in no longer involves spin recovery and only identifying when a spin is about to begin - called the "incipient spin recovery and therefore most aircraft will not be spun as part of non-military flight training. However, for military flight training, spinning will always be included and private aerobatic training will also always include spin training before other manoeuvres are taught. Being a capable aerobatic aircraft, it is also used at air show displays which are low level (so you can see it from the ground) and include advanced manoeuvres like spins and inverted spins, close to the ground.

Second reason - the Slingsby Firefly has a simple but different spin recovery technique published in the flight manual. If this procedure is not followed, the spin rate will initially increase and then stabilise in a spin all the way to the ground. However, following the published spin recovery procedure will recover from a spin in one and one-half turns or less. Quite why the accident pilots did not follow the published spin recovery technique could be a mystery, except that firstly it is common practice for pilots NOT to read the flight manual when getting a type rating, typically they learn the speed numbers and the weight and balance calculations required to obtain a rating. Additionally, it has been revealed that the US Air Force did not use the Slingsby Firefly manual at all for flight training. Instead they wrote their own manual. The published spin recovery technique involves using opposite rudder and then slowly moving the stick forward and expecting the spin rate to increase before it stops - the manual goes on - ″it may be required to push the stick all the way forward before the spin stops″. This is subtly different from most aircraft and somewhat counter-intuitive as you spin towards the ground. However the published spin recovery works effectively in every case, if you use it. See this British training video for how it should be done.

Specifications (T-3A)

Data from Brassey's World Aircraft & Systems Directory[10]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 24 ft 10 in (7.55 m)

- Wingspan: 34 ft 9 in (10.69 m)

- Height: 7 ft 9 in (2.36 m)

- Wing area: 136 ft² (12.6 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 23015/23013 (root/tip)

- Empty weight: 1,750 lb (794 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 2,550 lb (1,157 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Textron Lycoming AEIO-540-D 6-cylinder horizontally-opposed engine, 260 hp (194 kW)

Performance

- Never exceed speed: 195 knots (224mph, 361 km/h)

- Maximum speed: 152 knots (175 mph, 281 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 140 knots (161 mph, 259 km/h)

- Stall speed: 54 knots (62 mph, 100 km/h) (with flaps)

- Range: 407 nmi (468 mi, 753 km)

- Service ceiling: 19,000 ft [11] (5,790 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,380 ft/min (7 m/s)

- Wing loading: 18.8 lb/ft² (91.8 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.10 hp/lb (0.17 kW/kg)

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- PAC CT/4 (Pacific Aerospace Limited)

- T-41 Mescalero

References

- ↑ "Slingsby T67 Firefly". Marshall Slingsby. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ↑ "Prince Harry First Solo".

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 3 Hoyle Flight International 13–19 December 2011, p. 34.

- ↑ "The Fleet". Auckland Aero Club. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ↑ "Slingsby Firefly". North Shore Aero Club. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "Flight School and Aircraft". FTEJerez.

- ↑ "Swift Aircraft". Swift Aircraft. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, M J H (editor) (1999). Brassey's World Aircraft & Systems Directory 1999/2000 Edition. Brassey's. ISBN 1-85753-245-7.

- ↑ "FAS.org T-3A Firefly". Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International, Vol. 180, No. 5231, 13– 19 December 2011, pp. 26–52. ISSN 0015-3710.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slingsby T.67 Firefly. |

https://www.ntsb.gov/_layouts/ntsb.aviation/brief.aspx?ev_id=20141024X52246&key=1

- Official Canadian Forces T67 Firefly page

- UK Type Certificate for the T67 Firefly family

- Marshall Slingsby's Retrieved 18 June 2012

- Tom Cassell's Retrieved 18 June 2012

- Air Force Scrapping Troubled Plane Retrieved 9 September 2006

- AF link: Officials announce T-3A Firefly final disposition with public domain picture.