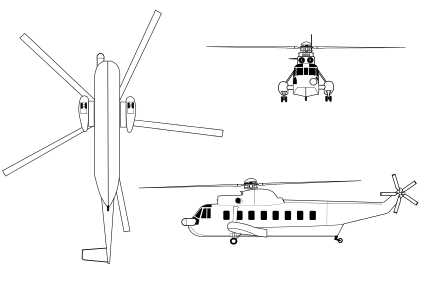

Sikorsky S-61

| S-61L/S-61N | |

|---|---|

| |

| A S-61N Mk.II operating for Sociedad de Salvamento y Seguridad Marítima in Spain | |

| Role | Medium-lift transport / airliner helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft |

| First flight | March 11, 1959 |

| Introduction | September 1961 |

| Status | Active service |

| Primary users | CHC Helicopter Bristow Helicopters AAR Airlift |

| Number built | 119[1] |

| Developed from | Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King |

The Sikorsky S-61L and S-61N are civil variants of the successful Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopter. They are two of the most widely used airliner and oil rig support helicopters built.[1]

Design and development

In September 1957, Sikorsky won a United States Navy development contract for an amphibious anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopter capable of detecting and attacking submarines.[1] The XHSS-2 Sea King prototype flew on 11 March 1959. Production deliveries of the HSS-2 (later designated SH-3A) began in September 1961, with the initial production aircraft being powered by two 930 kW (1250shp) General Electric T58-GE-8B turboshafts.

Sikorsky was quick to develop a commercial model of the Sea King.[1] The S-61L first flew on 2 November 1961, and was 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m) longer than the HSS-2 in order to carry a substantial payload of freight or passengers. Initial production S-61Ls were powered by two 1350shp (1005 kW) GE CT58-140 turboshafts, the civil version of the T58. The S-61L features a modified landing gear without float stabilisers.

Los Angeles Airways was the first civil operator of the S-61,[2] introducing them on 11 March 1962, for a purchased price of $650,000 each.[3]

The East Pakistan Helicopter Service used three S-61s. The service linked 20 East Pakistani towns, which made it one of the most extensive commercial helicopter networks at the time.[4]

On 7 August 1962, the S-61N made its first flight.[1] Otherwise identical to the S-61L, this version is optimized for overwater operations, particularly oil rig support, by retaining the SH-3's floats. Both the S-61L and S-61N were subsequently updated to Mk II standard with improvements including more powerful CT58-110 engines giving better hot and high performance, vibration damping and other detail refinements.

The Payloader, a stripped down version optimized for aerial crane work, was the third civil model of the S-61.[1] The Payloader features the fixed undercarriage of the S-61L, but with an empty weight almost 2,000 lb (910 kg) less than the standard S-61N.

Carson Helicopters was the first company to shorten a commercial S-61. The fuselage is shortened by 50 in (1.3 m) to increase single-engine performance and external payload.[5]

A unique version is the S-61 Shortsky conversion of S-61Ls and S-61Ns by Helipro International.[1] VIH Logging was the launch customer for the HeliPro Shortsky conversion, which first flew in February 1996.

One modification for the S-61 is the Carson Composite Main Rotor Blade. These blades replace the original Sikorsky metal blades, which are prone to fatigue, and permit a modified aircraft to carry an additional 2,000 lb (907 kg) load, fly 15 kn (28 km/h) faster and increase range 61 nmi (113 km).[5]

The latest version is the modernized S-61T helicopter. The United States Department of State has signed a purchase agreement for up to 110 modernized S-61T aircraft for passenger and cargo transport missions in support of its worldwide operations. The first two modernized S-61 aircraft will support missions for the U.S. Embassy in Afghanistan.[6]

Variants

- S-61L

- Non-amphibious civil transport version. It can seat up to 30 passengers[7]

- S-61L Mk II

- Improved version of the S-61L helicopter, equipped with cargo bins.[8]

- S-61N

- Amphibious civil transport version.[7]

- S-61N Mk II

- Improved version of the S-61N helicopter.[8]

- S-61NM

- An L model in an N configuration.[9]

- S-61T Triton

- S-61 modernized upgrade by Sikorsky and Carson; Upgrades include composite main rotor blades, full airframe structural refurbishment, conversion of folding rotor head to non-folding, new modular wiring harness, and Cobham glass cockpit avionics; initial models converted were S-61N[10]

Operators

.jpg)

- Croman Corporation [19]

- Helicopter Transport Services [20]

- United States Department of State [21]

Former operators

Notable accidents

- Pakistan International Airlines Flight 17 was a Sikorsky S-61 that crashed on 2 February 1966 on a scheduled domestic flight in East Pakistan with 23 killed and one survivor.

- On 22 May 1968, Los Angeles Airways Flight 841 crashed near Paramount, California, resulting in the loss of 23 lives. The accident aircraft, N303Y, serial number 61060, was a Sikorsky S-61L en route to Los Angeles International Airport from the Disneyland Heliport in Anaheim, California.

- On 14 August 1968, Los Angeles Airways Flight 417 crashed in Compton, California, while en route to the Disneyland Heliport in Anaheim, California from Los Angeles International Airport, resulting in the loss of 21 lives. The accident aircraft, N300Y, serial number 61031, was the prototype of the Sikorsky S-61L.[35]

- On 25 October 1973, a Greenlandair S-61N, OY-HAI "Akigssek" ("Grouse") crashed about 40 km south of Nuuk, resulting in the loss of 15 lives. It was en route to Paamiut from Nuuk. The same aircraft had an emergency landing on the Kangerlussuaq fjord two years earlier, due to flameout on both engines because of ice in the intake.[36]

- On 10 May 1974 KLM Noordzee Helikopters S-61N PH-NZC crashed en route to an oil rig in the North Sea. None of the two crew and four passengers survived. The probable cause was a failure in one of five rotor blades due to metal fatigue. The resulting imbalance caused the motor mounts to fail and resulted in a fire. The uncontrollable aircraft landed hard in the water, capsized and sank. Investigation indicated that the metal fatigue crack must have spread rapidly in less than four hours. The rotor blades are pressurized with nitrogen gas at 10 psi to indicate the onset of a metal fatigue failure, yet no pressure loss was indicated during the preflight inspection. As a result of the accident it was recommended to shorten inspection intervals[37] The aircraft was recovered from the North Sea floor. It was rebuilt and currently flies as registration N87580 in the USA.[38]

- On 16 May 1977, New York Airways' commercial S-61-L, N619PA, suffered a static rollover onto its starboard side at the heliport on top of the Pan Am Building while boarding passengers. The accident killed four boarding passengers and one woman on the street. 17 additional passengers and the three flight crew members were uninjured.[39] The landing gear collapse was a result of metal fatigue in the helicopter's main landing gear shock-absorbing strut assembly, which caused the helicopter to tip over without warning. The accident resulted in the permanent closure of the Pan Am Building heliport.[40] As the heliport was closed, the wreckage was removed by disassembling it and taking the assemblies down to street level using the building's freight elevators. The airframe was taken to Cape Town, South Africa, where it was rebuilt, certified and returned to service as the first S61 used in the Ship-Service Role off the shores of the Western Cape by the company "Court Helicopter" which was later amalgamated with CHC.[41]

- On 16 July 1983, British Airways Helicopters' commercial S-61 G-BEON crashed in the southern Celtic Sea, in the Atlantic Ocean, while en route from Penzance to St Mary's, Isles of Scilly in thick fog. Only six of the 26 on board survived. It sparked a review of helicopter safety and was the worst civilian helicopter disaster in the UK until 1986.

- On March 20, 1985, an Okanagan Helicopters S-61N (C-GOKZ) ditched in the Atlantic Ocean off of Owl's Head, Nova Scotia. The aircraft was en route from the MODU Sedco 709 offshore Nova Scotia to the Halifax International Airport(YHZ)when the main gearbox suffered a total loss of transmission fluid. There were 15 passengers and two crew on board. There were no injuries during the ditching, however several passengers suffered varying degrees of hypothermia. As a result of this incident, improved thermal protection and other advancements in helicopter transportation suits were instituted for offshore workers on Canada's east coast.

- 12 July 1988 a British International Helicopters S-61N ditched into the North Sea, no injuries.

- On 25 July 1990 a British International Helicopters Sikorsky S-61 registration 'G-BEWL' coming in from Sumburgh Airport crashed onto the Brent Spar oil storage platform as the pilots were attempting to land. The aircraft fell into the North Sea, where six of the 13 passengers and crew on board died.[42]

- On 8 July 2006, a Sociedad de Salvamento y Seguridad Marítima S-61N Mk.II search and rescue helicopter, crashed into the Atlantic Ocean while it was flying from Tenerife to La Palma. There were no survivors among the six people on board.

- On 5 August 2008, two pilots and seven firefighters assigned to the Iron Complex fire in California's Shasta–Trinity National Forest, were killed when Carson Helicopters S-61N N612AZ crashed on takeoff. Of the 13 people reportedly on board, one other pilot and three firefighters survived the crash with serious or critical injuries. The NTSB determined that the probable causes were the following actions by Carson Helicopters: 1) the intentional understatement of the helicopter’s empty weight, 2) the alteration of the power available chart to exaggerate lift capability, and 3) the use of unapproved above-minimum specification torque in performance calculations that, collectively, resulted in the pilots’ relying on performance calculations that significantly overestimated load-carrying capacity and without an adequate performance margin for a successful takeoff; and insufficient oversight by the U.S. Forest Service and the Federal Aviation Administration. Contributing factors were the flight crew's failure to address the fact that the helicopter had approached its maximum performance capability on two prior departures from the accident site as they were accustomed to operating at its performance limit. Contributing to the fatalities were the immediate, intense fire due to a fuel spillage upon impact from the fuel tanks that were not crash-resistant, the separation from the floor of the cabin seats that were not crash-resistant, and the use of an inappropriate release mechanism on the seat restraints.[43][44][45]

Specifications (S-61N Mk II)

Data from International Directiory of Civil Aircraft[1]

General characteristics

- Crew: two pilots

- Capacity: up to 30 passengers

- Length: 58 ft 11 in (17.96 m)

- Rotor diameter: 62 ft (18.9 m)

- Height: 17 ft 6 in (5.32 m)

- Disc area: 3,019 ft² (280.6 m²)

- Empty weight: 12,336 lb (5,595 kg)

- Loaded weight: 16,164 lb (7,332 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 19,000 lb (8,620 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric CT58-140 turboshafts, 1,500 shp (1,120 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 166 mph (267 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 120 kn (222 km/h)

- Range: 450 NM (833 km)

- Service ceiling: 12,500 ft (3,810 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,310–2,220 ft/min (400–670 m/min)

See also

Related development

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Frawley, Gerard: The International Directory of Civil Aircraft, 2003–2004, p. 194. Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd, 2003. ISBN 1-875671-58-7.

- ↑ Apostolo, G. "Sikorsky S-61".The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Helicopters. Bonanza Books, 1984. ISBN 0-517-43935-2.

- ↑ "The Self-Supporting Helicopter" Time Magazine December 26, 1960

- ↑ "Asia: Choppers over Pakistan". 13 December 1963. Retrieved 14 September 2017 – via content.time.com.

- 1 2 Carson Helicopters (2009). "About Carson Helicopters". Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ Press Releases: U.S. State Department Accepts Modernized S-61TM Helicopters for Use in Afghanistan

- 1 2 "VTOL AIRCRAFT 1967 pg. 712". Flightglobal Insight. 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- 1 2 "CIVIL V/STOL 1971 pg. 162". Flightglobal Insight. 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Airworthiness Directives Sikorsky Models S-61L, S-61N, and S-61NM". faa.gov. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Reed Business Information Limited. "HELI-EXPO: Sikorsky S-61T gains new life in State Department program". Flight Global. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "CHC Helicopter fleet". chc.ca. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Cougar Helicopters". cougar.ca. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Air Greenland fleet". airgreenland.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "World Air Forces 2013" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Bristow Helicopters fleet". bristowgroup.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "DOD Contracts Keep U.S. Helicopter Operators Busy in Afghanistan". ainonline.com. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Carson Helicopters Home page". carsonhelicopters.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Former employees of Carson Helicopters indicted over fatal Iron 44 Fire crash". wildfiretoday.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Croman Corporation Heavy Lift Svc". croman.net. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Helicopter Transport Services Aircraft". htshelicopters.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Sikorsky". www.sikorsky.com. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Coast Guard S-61 being retired from duty in Prince Rupert". helihub.com. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "Decision on £80m Air Corps helicopters contract due soon". irishtimes.com. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ↑ "End Of An Era As Irish Coast Guard's Last S61 Retires". afloat.ie. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ "Garda Cósta na hÉireann S-61". Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "KLM / Era Helicopters history". erahelicopters.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "KLM-Noordzee Helikopters S-61N". Demand media. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "World Helicopter Market 1967 pg. 63". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ "British Airways Helicopters". Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "British International Helicopters S-61". Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "HM Coastguard S-61N". Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Flight Int'l 1969 Pg. 581". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "New York Airways". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "World Helicopter Market 1968 pg. 57". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ↑ Aircraft Accident Report. Los Angeles Airways, Inc. S-61L Helicopter, N300Y, Compton, California Archived 2008-06-25 at the Wayback Machine., Adopted: August 27, 1969

- ↑ "Arktisk dokumentarkiv". arktiskleksikon.dk. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "1974". hdekker.info. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 10-MAY-1974 Sikorsky S-61N PH-NZC". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ UPI. Helicopter Crash Kills Five. Beaver County (Pa.) Times: Tuesday, 17 May 1977, A-13.

- ↑ Schneider, Daniel B. "F.Y.I.", July 25, 1999. Accessed September 30, 2007. "Q. Back in the 1960's and 70's, helicopters bound for Kennedy International Airport used to take off from a deck atop the old Pan Am Building. Why was the service halted? A. As many as 360 helicopter flights a day were planned by New York Airways after the 59-story Pan Am building was completed in 1963, but a bitter public outcry delayed the first few flights until December 21, 1965 ... The operation proved unprofitable, however, since the helicopters carried an average of only eight passengers, and the heliport, which had cost $1 million to build, closed in 1968 ... After another round of hearings – and renewed protests – flights resumed in February 1977. Three months later, the landing gear on one of the Sikorsky S-61 helicopters collapsed while passengers were boarding, flipping it on its side and sending a 20-foot rotor blade skidding across the roof and over the west parapet wall ... Within hours, the heliport was closed indefinitely."

- ↑ Epstein, Curt. HAI Convention News "An S-61 With a Past" October 26, 2010. Retrieved: June 13, 2011.

- ↑ UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch, Department of Transport, Report on the Accident to Sikorsky S-61N G-BEWL at Brent Spar, East Shetland Basin on 25 July 1990, retrieved 4 January 2014

- ↑ "Aircraft Accident Report Crash During Takeoff of Carson Helicopters, Inc., Firefighting Helicopter Under Contract to the U.S. Forest Service, Sikorsky S-61N, N612AZ Near Weaverville, California August 5, 2008 NTSB/AAR-10/06". ntsb.gov. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "USFA Fatality Notice". United States Fire Administration. 2008-08-06. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑

"FAA/NTSB Investigations". Los Angeles Injury Law Firm (See post #4 titled "Nine Firefighters Believed Dead After Helicopter Crash in California"). 2008-08-06. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 2009-02-03.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sikorsky S-61. |