Shqiptar

Shqip(ë)tar (plural: Shqiptarët; Gheg Albanian: Shqyptar[1]), is an Albanian language ethnonym (endonym), by which Albanians call themselves.[2][3] They call their country Shqipëria (Gheg Albanian: Shqipnia).[2]

History

During the Middle Ages, the Albanians called their country Arbëria (Gheg: Arbënia) and referred to themselves as Arbëresh (Gheg: Arbënesh) while known through derivative terms by neighbouring peoples as Arbanasi, Arbanenses / Albaneses, Arvanites (Arbanites), Arnaut, Arbineş and so on.[4][2][5][6][7][8] At the end of 17th and beginning of the early 18th centuries, the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëreshë amongst Albanian speakers.[2] This was due to socio-political, cultural, economic and religious complexities that Albanians experienced during the Ottoman era.[2][9] The usage of the old endonym Arbënesh/Arbëresh, however, persisted and was retained by Albanian communities which had migrated from Albania and adjacent areas centuries before the change of the self-designation, namely the Arbëreshë of Italy, the Arvanites of Greece as well as Arbanasi in Croatia.[10][11][12][13][14][15] As such, the medieval migrants to Greece and later migrants to Italy during the 15th-century are not aware of the term Shqiptar.[16]

Etymology

The theories about the etymology of the ethnic name Shqiptar:

- Gustav Meyer derived Shqiptar from the Albanian verbs shqipoj ("to speak clearly") and shqiptoj ("to speak out, pronounce"), which are in turn derived from the Latin verb excipere, denoting people who speak the same language, similar to the ethno-linguistic dichotomies Sloven—Nemac and Deutsch—Wälsch.[3] This is the theory also sustained by Robert Elsie[17] and Vladimir Orel.[18] Kristo Frashëri supported this and noted that it was first mentioned in the book Meshari (1555) of Gjon Buzuku.[19]

- Petar Skok suggested that the name originated from Scupi (Albanian: Shkupi), the capital of the Roman province of Dardania (today's Skopje); Albanian demonym Shkuptar (as in inhabitant of Skopje) changed to Shkiptar, and later to Shqiptar.

- The most accredited theory, at least among Albanians,[20] is that of Maximilian Lambertz, who derived Shqiptar from the Albanian noun shqipe or shqiponjë (eagle). The eagle was a common heraldic symbol for many Albanian dynasties in the Late Middle Ages and came to be a symbol of the Albanians in general, for example the flag of Skanderbeg, whose family symbol was the black double-headed eagle, as displayed on the Albanian flag.[21][22][23][24]

Non-Albanian usage

Use in Western Europe

Skipetar/s is a historical rendering or exonym of the term Shqiptar by some Western European authors in use from the late 18th century to the early 20th century.[25]

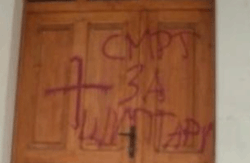

Use in South Slavic languages

The term Šiptar used in Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian (Cyrillic: Шиптар) is denoted in an offensive manner and it is also considered derogatory by Albanians when used by South Slavic peoples, due to its negative connotations.[26][27][28][29][30] After 1945, in pursuit of a policy of national equality, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia designated the Albanian community as ‘Šiptari’, however with increasing autonomy during the 1960s for Kosovo Albanians, their leadership requested and attained in 1974 the term Albanci (Albanians) be officially used stressing a national over an only ethnic, self-identification.[31] These developments resulted in the word Šiptari in Serbian usage acquiring pejorative connotations that implied Albanian racial and cultural inferiority.[31] It continued to be used by some Yugoslav and Serb politicians to relegate the status of Albanians to simply one of the minority ethnic groups.[31] The official term for Albanians in South Slavic languages is Albanac (Cyrillic: Албанац; plural: Albanci, Албанци).[31]

See also

References

- ↑ Fialuur i voghel Sccyp e ltinisct (Small Dictionary of Albanian and Latin), 1895, Shkodër

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lloshi, Xhevat (1999). “Albanian”. In Hinrichs, Uwe, & Uwe Büttner (eds). Handbuch der Südosteuropa-Linguistik. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 277.

- 1 2 Mirdita, Zef (1969). "Iliri i etnogeneza Albanaca". Iz istorije Albanaca. Zbornik predavanja. Priručnik za nastavnike. Beograd: Zavod za izdavanje udžbenika Socijalističke Republike Srbije. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history". London: Macmillan, 1998, p.29 "The name used in all these references is, allowing for linguistic variations, the same: 'Albanenses' or 'Arbanenses' in Latin, 'Albanoi' or 'Arbanitai' in Byzantine Greek. (The last of these, with an internal switching of consonants, gave rise to the Turkish form 'Arnavud', from which 'Arnaut' was later derived.)"

- ↑ Kamusella, Tomasz (2009).

- ↑ Robert Elsie (2010), Historical Dictionary of Albania, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, 75 (2 ed.), Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0810861886 "Their traditional designation, based on a root *alban- and its rhotacized variants *arban-, *albar-, and *arbar-, appears from the eleventh century onwards in Byzantine chronicles (Albanoi, Arbanitai, Arbanites), and from the fourteenth century onwards in Latin and other Western documents (Albanenses, Arbanenses)."

- ↑ Pinocacozza.it (Albanian) (Italian)

- ↑ Radio-Arberesh.eu (Italian)

- ↑ Kristo Frasheri. History of Albania (A Brief Overview). Tirana, 1964.

- ↑ 2017 Mate Kapović, Anna Giacalone Ramat, Paolo Ramat; "The Indo-European Languages"; page 554-555 "The name with the root arb- is mentioned in old Albanian documents, but it went out of use in the main part of Albanian-speaking area and remains in use only in diaspora dialects (It.-Alb. arbëresh, Gr.-Alb. arvanitas). In other areas, it has been replaced by the term with the root shqip-."

- ↑ Demiraj, Bardhyl (2010), pp. 534. "The ethnic name shqiptar has always been discussed together with the ethnic complex: (tosk) arbëresh, arbëror, arbër — (gheg) arbënesh, arbënu(e)r, arbën; i.e. [arbën/r(—)]. p.536. Among the neighbouring peoples and elsewhere the denomination of the Albanians is based upon the root arb/alb, cp. Greek ’Αλβανός, ’Αρβανός "Albanian", ‘Αρβανίτης "Arbëresh of Greece", Serbian Albanac, Arbanas, Bulg., Mac. албанец, Arom. arbinés (Papahagi 1963 135), Turk. arnaut, Ital. albanese, German Albaner etc. This basis is in use among the Arbëreshs of Italy and Greece as well.

- ↑ Lloshi, Xhevat (1999). “Albanian”. In Hinrichs, Uwe, & Uwe Büttner (eds). Handbuch der Südosteuropa-Linguistik. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 277, "They called themselves arbënesh, arbëresh, the country Arbëni, Arbëri, and the language arbëneshe, arbëreshe. In the foreign languages, the Middle Ages denominations of these names survived, but for the Albanians they were substituted by shqiptarë, Shqipëri and shqipe... Shqip spread out from the north to the south, and Shqipni/Shqipëri is probably a collective noun, following the common pattern of Arbëni, Arbëri."

- ↑ Skutsch, C. (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Taylor & Francis. p. 138. ISBN 9781135193881. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia; Jeffrey E. Cole - 2011, Page 15, "Arbëreshë was the term self-designiation of Albanians before the Ottoman invasion of the 15 century; similar terms are used for Albanian origins populations living in Greece ("Arvanitika," the Greek rendering of Arbëreshë) and Turkey ("Arnaut," Turkish for the Greek term Arvanitika)".

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history". London: Macmillan, 1998, p. 22–40 "The Albanians who use the 'Alb-' root are the ones who emigrated to Italy in the fifteenth century, who call themselves 'Arberesh'."

- ↑ Bartl 2001, p. 20

Данас уобичајени назив за Албанце, односно Албанију, shqiptar, Shqiperia, новијег је датума. Албанци који су се у средњем веку населили у Грчкој и они који су се у 15. веку и касније иселили у Италију у ствари не знају за ово име. Порекло назива shqiptar није једнозначно утврђено. Доскора је било омиљено тумачење да је изведен од албанског shqipe „властела, племство“, дакле „властелински синови“. Вероватније је, међутим, да је модеран назив који су Албанци себи дали изведен од shqipon „јасно рећи“ или од shqipton „изговорити“ (у поређењу са словенским називом немци „неми; они који не говоре разумљиво").

- ↑ Robert Elsie, A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2001, ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1, p. 79.

- ↑ Vladimir Orel (2000), A Concise Historical Grammar of the Albanian Language: Reconstruction of Proto-Albanian, Brill, p. 119

- ↑ Frashëri, Kristo. Etnogjeneza e shqiptarëve - Vështrim historik 2013

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/al.html

- ↑ Elsie 2010, "Flag, Albanian", p. 140.

- ↑ The Flag Bulletin. Flag Research Center. 1987-01-01.

- ↑ Hodgkison, Harry (2005). Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero. ISBN 1-85043-941-9.

- ↑ Kamusella 2009, p. 241.

- ↑ Demiraj, Bardhyl (2010). "Shqiptar–The generalization of this ethnic name in the XVIII century". In Demiraj, Bardhyl. Wir sind die Deinen: Studien zur albanischen Sprache, Literatur und Kulturgeschichte, dem Gedenken an Martin Camaj (1925-1992) gewidmet. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 533–565. ISBN 9783447062213.

- ↑ Paul Mojzes (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4422-0663-2.

- ↑ Franke Wilmer (16 April 2004). The Social Construction of Man, the State and War: Identity, Conflict, and Violence in Former Yugoslavia. Routledge. pp. 437–. ISBN 978-1-135-95621-9.

- ↑ Guzina, Dejan (2003). "Kosovo or Kosova – Could it be both? The Case of Interlocking Serbian and Albanian Nationalisms". In Florian Bieber and Židas Daskalovski (eds.). Understanding the war in Kosovo. Psychology Press. p.30.

- ↑ Neofotistos, Vasiliki P. (2010). "Cultural Intimacy and Subversive Disorder: The Politics of Romance in the Republic of Macedonia". Anthropological Quarterly. 83. (2): 288. (also see Lambevski 1997; for an analysis of the production and transgression of stereotypes, see Neofotistos 2004).

- ↑ Neofotistos, Vasiliki P. (2010). "Postsocialism, Social Value, and Identity Politics among Albanians in Macedonia". Slavic Review. 69. (4): 884-891.

- 1 2 3 4 Guzina 2003, pp. 32

There is similar terminological confusion over the name for the inhabitants of the region. After 1945, in pursuit of a policy of national equality, the Communist Party designated the Albanian community as ‘Šiptari’ (Shqiptare, in Albanian), the term used by Albanians themselves to mark the ethnic identity of any member of the Albanian nation, whether living in Albania or elsewhere.… However, with the increased territorial autonomy of Kosovo in the late 1960s, the Albanian leadership requested that the term ‘Albanians’ be used instead—thus stressing national, rather than ethnic, self-identification of the Kosovar population. The term ‘Albanians’ was accepted and included in the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution. In the process, however, the Serbian version of the Albanian term for ethnic Albanians—‘Šiptari’—had acquired an openly pejorative flavor, implying cultural and racial inferiority. Nowadays, even though in the documents of post- socialist Serbia the term ‘Albanians’ is accepted as official, many state and opposition party leaders use the term ‘Šiptari’ indiscriminately in an effort to relegate the Kosovo Albanians to the status of one among many minority groups in Serbia. Thus the quarrel over the terms used to identify the region and its inhabitants has acquired a powerful emotional and political significance for both communities.

Sources

- Guzina, Dejan (2003). "Kosovo or Kosova – Could it be both? The Case of Interlocking Serbian and Albanian Nationalisms". In Bieber, Florian; Daskalovski, Židas. Understanding the war in Kosovo. London: Psychology Press. pp. 31–52. ISBN 9780714653914.

Further reading

- Matzinger, Joachim (2013). "Shqip bei den altalbanischen Autoren vom 16. bis zum frühen 18. Jahrhundert [Shqip within Old Albanian authors from the 16th to the early 18th century]". Zeitschrift für Balkanologie. Retrieved 31 October 2015.