Shona people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 12 million (2000)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11 million (2000)[1] | |

| 173,000[2][3] | |

| 30,200[4][5] | |

| Languages | |

|

Shona, English Second or third language: Portuguese | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, African Traditional Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lemba, Kalanga, Venda and other Bantu peoples | |

| Shona | |

|---|---|

| Person | muShona |

| People | vaShona |

| Language | chiShona |

| Country | Mashonaland |

The Shona (/ˈʃoʊnə/) are a Bantu ethnic group native to Zimbabwe and neighbouring countries. The main part of them is divided into five major clans and adjacent to some people of very similar culture and languages. This name came into effect in the 19th century due to their skill of disappearing and hiding in caves when attacked. Hence Mzilikazi the great king called them amaShona meaning "those who just disappear". When the white settlers came to Mashonaland, they banned the Shona people from staying near caves and kopjes because of their hiding habits. This explanation is because there is no word called "Shona" in the Shona language vocabulary. There are various interpretations whom to subsume to the Shona proper and whom only to the Shona family.

Shona regional classification

The Shona people are divided into various tribes in the east regions of Zimbabwe.It is important not to mistake Bukalanga tribe of Matabeleland as these are a distinct clan of the Lozwi-Moyo Empire. Ethnologue notes that the language of the Bukalanga is mutually intelligible with the main dialects of the Eastern Shona as well as other Bantu languages in central and east of Africa, but counts them separately.

- Sure members (10.7 million):[6]

- Karanga or Southern Shona

- Duma

- Njiva(mrewa)

- Jena

- Mhari (Mari)

- Ngova

- Nyubi

- Govera

- Rozvi, sharing the Karanga dialect (about 4.5 million speakers and the largest group)

- Zezuru or Central Shona (3.2 million people, 11,000 of them in Botswana)

- Budya

- Gova

- Tande

- Tavara

- Nyongwe

- Pfunde

- Shan Gwe

- Korekore or Northern Shona (1.7 million people)

- Shawasha

- Gova

- Mbire

- Tsunga

- Kachikwakwa

- Harava

- Nohwe

- Njanja

- Nobvu

- Kwazwimba (Zimba)

- narrow Shona (1.3 million people)

- Toko

- Hwesa

- Karanga or Southern Shona

- Members or close relatives:

- Manyika[7] in Zimbabwe (861,000) and Mozambique (173,000). In Desmond Dale's basic Shona dictionary, also special vocabulary of Manyika dialect is included.[8]

- Kalanga (Western Shona),[9] in South-Western Zimbabwe, rather integrated in the Nguni culture, therefore little identification with the other Shona (700,000) and Botswana (150,000):

- Dhalaunda/Batalaote (they lived in Madzilogwe, Mazhoubgwe, up to Zhozhobgwe)

- Lilima (BaWombe; Bayela - are in the central district with Baperi)

- Baperi (live together with BaLilima as mentioned above)

- Banyai, speaking Nambya[10] in Zimbabwe (90,000) and Botswana (15,000), sometimes subsumed to the Western Shona

- Ndau[11] in Mozambique (1,580,000) and Zimbabwe (800,000). Their language is only partly intelligible with the main Shona dialects and comprises some click sounds that do not occur in standard ChiShona.

Language and identity

When the term Shona was invented during the Mfecane in late 19th century, possibly by the Ndebele king Mzilikazi, it was a pejorative for non-Nguni people. On one hand, it is claimed that there was no consciousness of a common identity among the tribes and peoples now forming the Shona of today. On the other hand, the Shona people of Zimbabwe highland always had in common a vivid memory of the ancient kingdoms, often identified with the Monomotapa state. The terms "Karanga"/"Kalanga"/"Kalaka", now the names of special groups, seem to have been used for all Shona before the Mfecane.[12]

Dialect groups are important in Shona although there are huge similarities among the dialects. Although 'standard' Shona is spoken throughout Zimbabwe, the dialects not only help to identify which town or village a person is from (e.g. a person who is Manyika would be from Eastern Zimbabwe, i.e. towns like Mutare) but also the ethnic group which the person belongs to. Each Shona dialect is specific to a certain ethnic group, i.e. if one speaks the Manyika dialect, they are from the Manyika group/tribe and observe certain customs and norms specific to their group. As such, if one is Zezuru, they speak the Zezuru dialect and observe those customs and beliefs that are specific to them.

In 1931, during the process of trying to reconcile the dialects into the single standard Shona, Professor Clement Doke[13] identified six groups, each with subdivisions:

- The Korekore or Northern Shona, including Taυara, Shangwe, Korekore proper, Goυa, Budya, the Korekore of Urungwe, the Korekore of Sipolilo, Tande, Nyongwe of "Darwin", Pfungwe of Mrewa;

- The Zezuru group, including Shawasha, Haraυa, another Goυa, Nohwe, Hera, Njanja, Mbire, Nobvu, Vakwachikwakwa, Vakwazvimba, Tsunga;

- The Karanga group, including Duma, Jena, Mari, Goυera, Nogoυa, Nyubi;

- The Manyika group, including Hungwe, Manyika themselves, Teυe, Unyama, Karombe, Nyamuka, Bunji, Domba, Nyatwe, Guta, Bvumba, Here, Jindwi, Boca;

- The Ndau group (mostly Mozambique), including Ndau themselves, Garwe, Danda, Shanga;

The above differences in dialects developed during the dispersion of tribes across the country over a long time. The influx of immigrants, into the country from bordering countries, has obviously contributed to the variety.

Shona culture

There are more than ten million people who speak a range of related dialects whose standardized form is also known as Shona.

Subsistence

The Shona are traditionally agricultural. Their crops were sorghum (in modern age replaced by maize), yam, beans, bananas (since middle of the first millennium), African groundnuts, and, not before the 16th century, pumpkins. Sorghum and maize are used to prepare the main dish, a thickened porridge called sadza, and the traditional beer, called hwahwa.[14] The Shona also keep cattle and goats, in history partly as transhumant herders. The livestock had a special importance as a food reserve in times of drought.[15]

Already the precolonial Shona states received a great deal of their revenues from the export of mining products, especially gold and copper.[15]

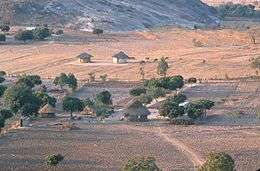

Housing

In their traditional homes, called musha, they had (and have) separate round huts for the special functions, such as kitchen and lounging around a yard (ruvanze) cleared from ground vegetation.[16]

Arts and crafts

The Shona are known for the high quality of their stone sculptures.

Also traditional pottery is of a high level.

Traditional textile production was expensive and of high quality. People preferred to wear skins or imported tissues.[15]

Shona traditional music, in contrast to European tradition but embedded in other African traditions, tends to constant melodies and variable rhythms. The most important instrument besides drums is the mbira. Singing is also important and families would group together and sing traditional songs.

History

The term Shona is as recent as the 1920s.

Kingdoms

The Karanga, from the 11th century, created empires and states on the Zimbabwe plateau. These states include the Great Zimbabwe state (12-16th century), the Torwa State, and the Munhumutapa states, which succeeded the Great Zimbabwe state as well as the Rozwi state, which succeeded the Torwa State, and with the Mutapa state existed into the 19th century. The states were based on kingship with certain dynasties being royals.

The major dynasties were the Rozwi of the Moyo (Heart) Totem, the Elephant (of the Mutapa state), and the Hungwe (Fish Eagle) dynasties that ruled from Great Zimbabwe. The Karanga who speak Chikaranga are related to the Kalanga possible through common ancestry, however this is still debatable. These groups had an adelphic succession system (brother succeeds brother) and this after a long time caused a number of civil wars which, after the 16th century, were taken advantage of by the Portuguese. Underneath the king were a number of chiefs who had sub-chiefs and headmen under them.[15]

Decay

The kingdoms were destroyed by new groups moving onto the plateau. The Ndebele destroyed the Chaangamire's Lozwi state in the 1830s, and the Portuguese slowly eroded the Mutapa State, which had extended to the coast of Mozambique after the state's success in providing valued exports for the Swahili, Arab and East Asian traders, especially in the mining of gold, known by the pre-colonisation miners as kuchera dyutswa. The British destroyed traditional power in 1890 and colonized the plateau of Rhodesia. In Mozambique, the Portuguese colonial government fought the remnants of the Mutapa state until 1902.[15]

Beliefs

Nowadays, between 60% and 80% of the Shona are Christians. Besides that, traditional beliefs are very vivid among them.[17] The most important features are ancestor-worship (the term is called inappropriate by some authors) and totemism.

Ancestors

According to Shona tradition, the afterlife does not happen in another world like Christian heaven and hell, but as another form of existence in the world here and now. The Shona attitude towards dead ancestors is very similar to that towards living parents and grandparents.[18]

Nevertheless, there is a famous ritual to contact the dead ancestors. It is called Bira ceremony and often lasts all night.

The Shona believe in heaven and have always believed in it. They don't talk about it because they don't know what is there so there is no point. When people die they either go to heaven or they don't. What is seen as ancestor worship is nothing of the sort. When a man died, God (Mwari) was petitioned to tell his people if he was now with Him. They would go into a valley surrounded by mountains on a day when the wind was still.

An offering would be made to Mwari and wood reserved for such occasions would be burnt. If the smoke from the fire went up to heaven the man was with Mwari; if it dissipated then he was not. If he was with Mwari then he would be seen as the new intercessor to Him. There were always three intercessors so the Shona prayed somewhat along these lines:

To our grandfather Tichivara we ask that you pass on our message to our great-grandfather Madzingamhepo so he can pass it on to our great-great-grandfather Mhizhahuru who will in turn pass it to the creator of all, the bringer of rain, the master of all we see, he who sees to our days, the ancient one (these are just examples of the meanings of the names of God. To show respect to him the Shona listed about thirty or so of his names starting with the common and getting to the more complex and or ambiguous ones like...) Nyadenga- the heaven who dwells in heaven, Samatenga- the heavens who dwells in the heavens, our father... Then they would describe what they needed.

His true name, Mwari, was too sacred to be spoken in everyday occasions and was reserved for high ceremonies and the direst of need as it showed Him disrespect to be free with it. As a result, God had many names, all of which would be recognised as His even by people who had never heard the name before. He was considered too holy to just go to straight up, hence the need for ancestral intercessors. With each new one the oldest was let go.

When the missionaries came, they talked about Jesus being the universal intercessor, which made sense as there were conflicts in the society, with some people wanting their so-and-so, who they believed was with God, to be included in intercession. Doing away with ancestral intercessors made sense.

However they made no effort to know how the Shona prayed and violently insisted they drop the other gods (i.e., the different names for God) and keep the high name Mwari. To the Shona this sounded like 'to get to God all you need to do is disrespect him in the most profound way', as leaving out his names in prayer was the highest form of disrespect.

The missionaries would not drink water from the Shona, the first form of hospitality required in the tribe. They would not eat the same food as the Shona, another thing God encouraged.

Added to that, Matopos hill and the land around it was considered the most fertile land in Mashonaland and was reserved for God. John Rhodes took that land as his and chased away the caretakers of the land. People could no longer go there to petition God.

All of which led people to hold on to ancestral intercessors all the more. Jesus was seen as a universal intercessor but as his messengers lacked 'proper manners' it reinforced ancestral intercessors.

The modern form devolved from the original as most ceremonies for God were outlawed, and families were displaced and separated. The only thing left was to hold on to their ancestors. Still if you ask the so-called ancestor worshippers about their religion they would tell you they are Christians.

Totems

In Zimbabwe, totems (mutupo) have been in use among the Shona people since the initial development of their culture. Totems identify the different clans among the Shona that historically made up the dynasties of their ancient civilization. Today, up to 25 different totems can be identified among the Shona, and similar totems exist among other South African groups, such as the Tswana, Zulu, the Ndebele, and the Herero.[19]

People of the same clan use a common set of totems. Totems are usually animals and body parts. Examples of animals totems include Shiri/Hungwe (Fish Eagle), Mhofu/Mhofu Yemukono/Musiyamwa (Eland), Mbizi/Tembo (Zebra), Shumba (Lion), Mbeva/Hwesa/Katerere (Mouse), Soko (Monkey), Nzou (Elephant), Ngwena (crocodile), and Dziva (Hippo). Examples of body part totems include Gumbo (leg), Moyo (heart), and Bepe (lung). These were further broken down into gender related names. For example, Zebra group would break into Madhuve for the females and Dhuve or Mazvimbakupa for the males. People of the same totem are the descendants of one common ancestor (the founder of that totem) and thus are not allowed to marry or have an intimate relationship. The totems cross regional groupings and therefore provide a wall for development of ethnicism among the Shona groups.

Shona chiefs are required to be able to recite the history of their totem group right from the initial founder before they can be sworn in as chiefs.

Orphans

The totem system is a severe problem for many orphans, especially for dumped babies.[20] People are afraid of being punished by ghosts, if they violate rules connected with the unknown totem of a foundling. Therefore, it is very difficult to find adoptive parents for such children. And if the foundlings have grown up, they have problems getting married. [21]

Burials

The identification by totem has very important ramifications at traditional ceremonies such as the burial ceremony. A person with a different totem cannot initiate burial of the deceased. A person of the same totem, even when coming from a different tribe, can initiate burial of the deceased. For example, a Ndebele of the Mpofu totem can initiate burial of a Shona of the Mhofu totem and that is perfectly acceptable in Shona tradition. But a Shona of a different totem cannot perform the ritual functions required to initiate burial of the deceased.

If a person initiates the burial of a person of a different totem, he runs the risk of paying a fine to the family of the deceased. Such fines traditionally were paid with cattle or goats but nowadays substantial amounts of money can be asked for. If they bury their dead family members, they would come back at some point to cleanse the stone of the burial. if someone bets his or her parents he would suffer after death of the parents due to their spirit.

References

- 1 2 Ehnologue: Languages of Zimbabwe Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine., citing Chebanne, Andy and Nthapelelang, Moemedi. 2000. The socio-linguistic survey of the Eastern Khoe in the Boteti and Makgadikgadi Pans areas of Botswana.

- ↑ Ethnologue: Languages of Mozambique

- ↑ Ethnologue: Languages of Botswana

- ↑ Ethnologue: Languages of Zambia

- ↑ Joshua project: South Africa

- ↑ Ehnologue: Shona

- ↑ Ethnologue: Manyika

- ↑

- ↑ Ethnologue: Kalanga

- ↑ Ethnologue: Nambya

- ↑ Ethnologue: Ndau

- ↑ Zimbabwes rich totem strong families – a euphemistic view on the totem system Archived 2015-05-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Doke, Clement M.,A Comparative Study in Shona Phonetics. 1931. University of Witwatersrand Press, Johannesburg.

- ↑ Correct spelling according to D. Dale, A basic English Shona Dictionary, mambo Press, Gwelo (Gweru) 1981; some sources write "whawha", misled by conventions of English words like "what".

- 1 2 3 4 5 David N. Beach: The Shona and Zimbabwe 900–1850. Heinemann, London 1980 und Mambo Press, Gwelo 1980, ISBN 0-435-94505-X.

- ↑ Friedrich Du Toit, Musha: the Shona concept of home, Zimbabwe Pub. House, 1982

- ↑ http://www.everyculture.com/Africa-Middle-East/Shona-Religion-and-Expressive-Culture.html

- ↑ Michael Gelfand, The spiritual beliefs of the Shona, Mambo Press 1982, ISBN 0-86922-077-2, with a preface by Referent Father M. Hannan.

- ↑ Totem Author: Magelah Peter - Published: May 21, 2007, 4:56 am

- ↑ Baby dumping in Zimbabwe

- ↑ Orphan for Life

.jpg)