Shane (film)

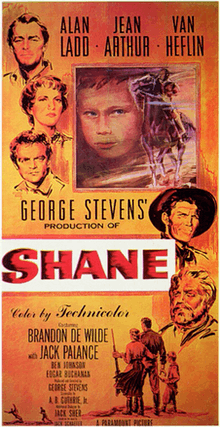

| Shane | |

|---|---|

theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | George Stevens |

| Produced by | George Stevens |

| Screenplay by |

A.B. Guthrie, Jr. Jack Sher |

| Based on |

Shane 1949 novel by Jack Schaefer |

| Starring |

Alan Ladd Jean Arthur Van Heflin Brandon deWilde Jack Palance |

| Music by | Victor Young |

| Cinematography | Loyal Griggs |

| Edited by |

William Hornbeck Tom McAdoo |

Production company |

Paramount Pictures |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.1 million |

| Box office | $20,000,000[1] |

Shane is a 1953 American Technicolor Western film from Paramount Pictures,[2][3] noted for its landscape cinematography, editing, performances, and contributions to the genre.[4] The picture was produced and directed by George Stevens from a screenplay by A. B. Guthrie Jr.,[5] based on the 1949 novel of the same name by Jack Schaefer.[6] Its Oscar-winning cinematography was by Loyal Griggs. Shane stars Alan Ladd and Jean Arthur in the last feature (and only color) film of her career.[7] The film also stars Van Heflin and features Brandon deWilde, Jack Palance, Emile Meyer, Elisha Cook Jr., and Ben Johnson.[4][5]

Shane was listed No. 45 in the 2007 edition of AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies list, and No. 3 on AFI's 10 Top 10 in the 'Western' category.

Plot

Shane, a skilled, laconic gunfighter with a mysterious past,[4] rides into an isolated valley in the sparsely settled Wyoming Territory, some time after the Civil War. At dinner with local rancher Joe Starrett and his wife Marian, he learns that a war of intimidation is being waged on the valley's settlers. Though they have claimed their land legally under the Homestead Acts, a ruthless cattle baron, Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer), has hired rogues and henchmen to harass them and drive them out of the valley. Starrett offers Shane a job, and he accepts.

At the town's general store, Shane and other homesteaders are loading up supplies. Shane enters the saloon adjacent to the store, where Ryker's men are drinking, and orders a soda pop for the Starretts' son, Joey. Chris Calloway, one of Ryker's men, throws a shot of whiskey on Shane's shirt. "Smell like a man!" he taunts. Shane doesn't rise to the bait, and leaves to the taunts of Ryker's men. On the next trip to town, Shane returns the empty soda bottle to the saloon, where Calloway again taunts him. Shane orders two shots of whiskey, pours one on Calloway's shirt and throws the other in his face, then knocks him to the ground. A brawl ensues; Shane prevails, with Starrett's help. Ryker declares that the next time they meet, "the air will be filled with gun smoke."

Joey is drawn to Shane, and to his gun. Shane shows him how to wear a holster and demonstrates his shooting skills, but Marian interrupts the lesson. Guns, she says, are not going to be a part of her son's life. Shane counters that a gun is a tool, no better nor worse than an axe or a shovel, and as good or bad as the man using it. Marian retorts that the valley would be better off without any guns—including Shane's.

Jack Wilson, an unscrupulous gunfighter working for Ryker, deliberately provokes Frank "Stonewall" Torrey, a hot-tempered ex-Confederate homesteader. When the inexperienced farmer goes for his gun, Wilson shoots him dead. At Torrey's funeral, there is talk among the settlers of giving in to Ryker and moving on; but after battling a fire set by Ryker's men, they find new determination and resolve to continue the fight.

Ryker invites Starrett to a meeting at the saloon to negotiate a settlement—and then orders Wilson to kill him when he arrives. Calloway, unable to tolerate Ryker's treachery any longer, warns Shane of the double-cross. Starrett says no matter, he will shoot it out with Wilson, and asks Shane to look after Marian and Joey if he dies. Shane, aware that Starrett is no match for Wilson in a gunfight, says he must go instead. Starrett is adamant, and Shane is forced to knock him unconscious. A distraught Marian asks Shane why he is doing this. For her, he replies, and her husband and son, and all the other decent people who want a chance to live in peace in the valley.

As Shane rides to town, Joey follows him on foot. At the saloon, he beats Wilson to a draw, then shoots Ryker as he draws a hidden gun. Shane tells Joey to tell his mother that the settlers have won, and he must leave. His left arm hangs limply at his side as he mounts his horse. Shane rides out of town, ignoring Joey's desperate cries of "Shane! Come back!"

Cast

- Alan Ladd as Shane

- Jean Arthur as Marian Starrett

- Van Heflin as Joe Starrett

- Brandon deWilde as Joey Starrett

- Jack Palance (credited as Walter Jack Palance) as Jack Wilson

- Ben Johnson as Chris Calloway

- Edgar Buchanan as Fred Lewis

- Emile Meyer as Rufus Ryker

- Elisha Cook Jr. as Frank "Stonewall" Torrey

- Douglas Spencer as Axel 'Swede' Shipstead

- John Dierkes as Morgan Ryker

- Ellen Corby as Mrs. Liz Torrey

- Paul McVey as Sam Grafton

- John Miller as Will Atkey, bartender

- Edith Evanson as Mrs. Shipstead

- Leonard Strong as Ernie Wright

- Nancy Kulp as Mrs. Howells

Production

Shane was expensive for a Western movie at the time with a cost of $3.1 million.[8] It was the first film to be projected in "flat" widescreen, a format that Paramount invented in order to offer audiences a wider panorama than television could provide.[9]

Director George Stevens originally wanted Montgomery Clift and William Holden for the Shane and Starrett roles; when both proved unavailable, Stevens asked Paramount executive Y. Frank Freeman for a list of available actors with current contracts; within three minutes he chose Alan Ladd, Van Heflin, and Jean Arthur. Shane was Arthur's first cinematic role in five years, and her last, at the age of 50—though she later appeared in theater, and a short-lived television series. She accepted the part at the request of Stevens, who had directed her in The Talk of the Town (1942) and The More the Merrier (1943) for which she received her only Oscar nomination.[10]

Although never explicitly stated, the basic plot elements of Shane were derived from the 1892 Johnson County War in Wyoming, the archetypal cattlemen–homesteaders conflict, which also served as the background for The Virginian and Heaven's Gate.[11] The physical setting is the high plains near Jackson, Wyoming, and many shots feature the Grand Teton massif looming in the near distance. The fictional town and Starrett homestead were constructed for the film near Kelly, in the Jackson Hole valley, and demolished after filming was completed. One vintage structure that appeared briefly in the film, the Ernie Wright Cabin (now popularly referred to by locals as the "Shane Cabin") still stands, but is steadily deteriorating due to its classification as "ruins" by the National Park Service.[12]

Ladd was uncomfortable with guns; Shane's shooting demonstration for Joey required 116 takes.[13] Palance was nervous around horses, and had great difficulty with mounting and dismounting. After many attempts, he finally executed a flawless dismount, which Stevens then used for all of the Wilson character's dismounts and—run in reverse—his mounts as well. Palance looked so awkward on horseback that Stevens was forced to replace Wilson's introductory ride into town astride his galloping horse with Palance on foot, leading the horse.[14] Stevens later noted that the change made Wilson's entrance more dramatic and menacing.[15]

The final scene, in which the wounded Shane explains to a distraught Joey why he has to leave ("There's no living with a killing"), was a moving moment for the entire cast and crew, except Brandon deWilde. "Every time Ladd spoke his lines of farewell, deWilde crossed his eyes and stuck out his tongue. Finally, Ladd called to the boy's father, 'Make that kid stop or I'll beat him over the head with a brick.' DeWilde behaved."[14]

Technical details

Although the film's image was shot using the standard 1.37:1 Academy ratio, Paramount picked Shane to debut their new wide-screen system because it was composed largely of long and medium shots that would not be compromised by cropping the image. Using a newly cut aperture plate in the movie projector, as well as a wider-angle lens, the film was exhibited in first-run venues at an aspect ratio of 1.66:1. For its premier, the studio replaced the 34-by-25-foot screen in Radio City Music Hall with one measuring 50 feet wide by 30 feet high.[16][17]Paramount produced all of its subsequent films at that ratio until 1954, when they switched to 1.85:1.[9] Shane was originally released in April 1953 with a conventional optical soundtrack; but as its popularity grew, a new three-track, stereophonic soundtrack was recorded and played on an interlocking 35mm magnetic reel in the projection booth.[18]

Stevens wanted to demonstrate to audiences "the horrors of violence". To emphasize the terrible power of gunshots, he created a cannon-like sound effect by firing a large-calibre weapon into a garbage can. In addition, he had the two principal shooting victims—Palance and Elisha Cook Jr.—rigged with hidden wires that jerked them violently backward when shot. These innovations, according to film historian Jay Hyams, marked the beginning of graphic violence in Western movies. He quotes Sam Peckinpah: "When Jack Palance shot Elisha Cook Jr. in Shane, things started to change."[11]

Reception

—Henry Winkler as Arthur Fonzarelli, Happy Days[11]

Shane premiered in New York City at Radio City Music Hall on April 23, 1953,[17] and grossed $114,000 in its four weeks there.[19] In all, the film earned $8 million in North America over its initial run.[20]

Bosley Crowther called the film a "rich and dramatic mobile painting of the American frontier scene". He continued:

Shane contains something more than the beauty and the grandeur of the mountains and plains, drenched by the brilliant Western sunshine and the violent, torrential, black-browed rains. It contains a tremendous comprehension of the bitterness and passion of the feuds that existed between the new homesteaders and the cattlemen on the open range. It contains a disturbing revelation of the savagery that prevailed in the hearts of the old gun-fighters, who were simply legal killers under the frontier code. And it also contains a very wonderful understanding of the spirit of a little boy amid all the tensions and excitements and adventures of a frontier home.

Crowther called "the concept and the presence" of Joey, the little boy played by Brandon deWilde, "key to permit[ting] a refreshing viewpoint on material that's not exactly new. For it's this youngster's frank enthusiasms and naive reactions that are made the solvent of all the crashing drama in A. B. Guthrie Jr.'s script."[21]

Woody Allen has called Shane "George Stevens' masterpiece", on his 2001 list of great American films, along with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, White Heat, Double Indemnity, The Informer and The Hill. Shane, he wrote, "... is a great movie and can hold its own with any film, whether it's a Western or not."[22]

Influence on later works

The 2017 film Logan drew substantial thematic influence from Shane, and formally acknowledged it with a series of specific dialog references and scene clips. As the film ends, Shane's farewell words to Joey are recited, verbatim, at the title character's grave.[23]

The 1985 film Pale Rider has a similar plot.

In the 1998 film The Negotiator, the two leading characters have a discussion about Western Genre films, Shane in particular. Mainly about the ending, where one character says Shane died, and the other says “he’s slump cause he’s shot, and shot don’t mean dead”.

Awards and honors

- Academy Award

- Academy Award for Best Cinematography, Color: Loyal Griggs; 1954

- Academy Award nominations

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role: Brandon deWilde

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role: Jack Palance

- Best Director: George Stevens

- Best Picture: George Stevens

- Best Writing, Screenplay: A.B. Guthrie, Jr.

- American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies: No. 69

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition): No. 45

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains: Shane, Hero No. 16

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes: "Shane. Shane. Come back!", No. 47

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers: No. 53

- AFI's 10 Top 10: No. 3 Western[24]

- Other

In 1993, Shane was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".

Copyright status in Japan

In 2006 Shane was the subject of litigation in Japan involving its copyright status in that country. Two Japanese companies began selling budget-priced copies of Shane in 2003, based on a Japanese copyright law that, at the time, protected cinematographic works for 50 years from the year of their release. After the Japanese legislature amended the law in 2004 to extend the duration of motion picture copyrights from 50 to 70 years, Paramount and its Japanese distributor filed suit against the two companies. A Japanese court ruled that the amendment was not retroactive, and therefore any film released during or prior to 1953 remained in the public domain in Japan.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Box Office Information for Shane. The Numbers. Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ↑ Variety film review; April 15, 1953, page 6.

- ↑ Harrison's Reports film review; April 18, 1953, page 63.

- 1 2 3 Andrew, Geoff. "Shane", Time Out Film Guide, Time Out Guides Ltd., London, 2006.

- 1 2 "Shane". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ Schaefer, Jack (1983). Shane (Paperback ed.). New York City: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553271102.

- ↑ Vermilye 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ "Berlin Analyzes Goldwyn's Show-Cents". Variety. March 10, 1954. p. 2.

- 1 2 Weaver, William R. (March 25, 1953). "All Para. Films Set for 3 to 5 Aspect Ratio". Motion Picture Daily. p. 1.

- ↑ Brady & 1950-A, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Hyams 1984, p. 115.

- ↑ Shane Movie Locations at bestofthetetons.com, retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ↑ Turner Classic Movies, TCM.com, "'Shane' (1953) - Trivia" Retrieved 2015-08-08

- 1 2 Hyams 1984, p. 116.

- ↑ Shane at RogerEbert.com, retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Hall Alters Projection Equipment for 'Shane'". Motion Picture Daily, April 8, 1953.

- 1 2 Lev 2003, p. 116.

- ↑ "Midwest 'Shane' Premiere at Lake". Motion Picture Daily, May 13, 1953.

- ↑ "'Wax,' 'Shane' End Sturdy B'Way Runs". Motion Picture Daily, May 20, 1953.

- ↑ "All Time Domestic Champs", Variety, 6 January 1960 p. 34

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (April 24, 1953). "Shane (1953)". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ Lyman, Rick (August 3, 2001). "Watching Movies With: Woody Allen; Coming Back To 'Shane'". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ What was that Western Movie in Logan? at geekendgladiators.com, retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Top Western". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ Mitani, Hidehiro (Autumn–Winter 2007). "Argument for the Extension of the Copyright Protection over Cinematographic Works". CASRIP Newsletter. UW School of Law. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

Sources

- Vermilye, Jerry (2012). Jean Arthur: A Biofilmography. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. p. 143. ISBN 978-1467043274.

- Hyams, Jay (1984). The Life and Times of the Western Movie (1st ed.). New York City: Gallery Books. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0831755454.

- Brady, Thomas F. (March 1, 1950). "Paramount Gets Option on Novel: to Enact Title Role". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. p. 42. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- Brady, Thomas F. (March 24, 1950). "Warners Acquire 'Winterset' Rights: Studio Buys Screen Privilege From R.K.O. and May Star Humphrey Bogart in It Of Local Origin". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. p. 29. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- NY Times Staff (September 27, 1950). "Alan Ladd to Star in Historical Film: He Will Appear in 'Quantrell's Raiders,' Which Wallis Will Produce at Paramount U.-I. Buys "Fifth Estate"". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. p. 48. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- van Heerden, Bill (1998). Film and Television In-Jokes: Nearly 2,000 Intentional References, Parodies, Allusions, Personal Touches, Cameos, Spoofs and Homages (Paperback ed.). McFarland & Company. p. 162. ISBN 978-1476612065.

Cliff Robertson appears as the villain Shame (a takeoff on Alan Ladd's western hero, Shane, 1953)

- Lev, Peter (2003). Transforming the Screen, 1950-1959. Oakland, California: University of California Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780520249660.

Further reading

- Walt Farmer (2001). The Making of Shane in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. CD-ROM.

- Slotkin, Richard (1992). "Killer Elite: The Cult of the Gunfighter, 1950–1953". Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America. New York: HarperPerennial. pp. 379–404. ISBN 0-06-097575-X.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Shane (film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shane (film). |

- Shane on IMDb

- Shane at the TCM Movie Database

- Shane at AllMovie

- Shane at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Shane at Rotten Tomatoes

- Shane at Filmsite.org