Secondary sex characteristic

Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty in humans, and at sexual maturity in other animals. These are particularly evident in the sexually dimorphic phenotypic traits that distinguish the sexes of a species, but unlike the sex organs, are not directly part of the reproductive system. They are believed to be the product of sexual selection for traits which display fitness, giving an individual an advantage over its rivals in courtship and aggressive interactions. They are distinguished from the primary sex characteristics, the sex organs, which are directly necessary for sexual reproduction to occur.

Secondary sex characteristics include manes of male lions and long feathers of male peacock, the tusks of male narwhals, enlarged proboscises in male elephant seals and proboscis monkeys, the bright facial and rump coloration of male mandrills, and horns in many goats and antelopes, and these are believed to be produced by a positive feedback loop known as the Fisherian runaway produced by the secondary characteristic in one sex and the desire for that characteristic in the other sex. Male birds and fish of many species have brighter coloration or other external ornaments. Differences in size between sexes are also considered secondary sexual characteristics.

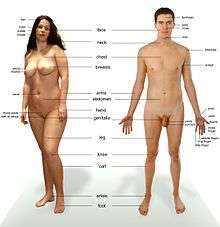

In humans, visible secondary sex characteristics include pubic hair, enlarged breasts and widened hips of females, and facial hair and Adam's apple on males.

Evolutionary roots

Charles Darwin hypothesized that sexual selection, or competition within a species for mates, can explain observed differences between sexes in many species.[1] Biologists today distinguish between "male-to-male combat" and "mate choice", usually female choice of male mates. Sexual characteristics due to combat are such things as antlers, horns, and greater size. Characteristics due to mate choice, often referred to as ornaments, include brighter plumage, coloration, and other features that have no immediate purpose for survival or combat.

Ronald Fisher, the English biologist developed a number of ideas concerning secondary characteristics in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, including the concept of Fisherian runaway which postulates that the desire for a characteristic in females combined with that characteristic in males can create a positive feedback loop or runaway where the feature becomes hugely amplified. The 1975 handicap principle extends this idea, pointing out that a peacock's tail, for instance, displays fitness by being a useless impediment that is very hard to fake. Another of Fisher's ideas is the sexy son hypothesis, whereby females will desire to have sons that possess the characteristic that they find sexy in order to maximize the number of grandchildren they produce.[2] An alternative hypothesis is that some of the genes that enable males to develop impressive ornaments or fighting ability may be correlated with fitness markers such as disease resistance or a more efficient metabolism. This idea is known as the good genes hypothesis.

Male jumping spiders have visual patches of UV reflectance, which are ornamentations used to attract females.[3]

In humans

Sexual differentiation begins during gestation, when the gonads are formed. The general structure and shape of the body and face, as well as sex hormone levels, are similar in preadolescent boys and girls. As puberty begins and sex hormone levels rise, differences appear, though some changes are similar in males and females. Male levels of testosterone directly induce the growth of the genitals, and indirectly (via dihydrotestosterone (DHT)) the prostate. Estradiol and other hormones cause breasts to develop in females. However, fetal or neonatal androgens may modulate later breast development by reducing the capacity of breast tissue to respond to later estrogen.[4][5][6]

Females

In females, breasts are a manifestation of higher levels of estrogen; estrogen also widens the pelvis and increases the amount of body fat in hips, thighs, buttocks, and breasts. Estrogen also induces growth of the uterus, proliferation of the endometrium, and menses.

- Enlargement of breasts and erection of nipples.[7]

- Growth of body hair, most prominently underarm and pubic hair

- Greater development of thigh muscles behind the femur, rather than in front of it (as is typical in mature males)

- Widening of hips;[8] lower waist to hip ratio than adult males

- Elbows that hyperextend 5-8° more than male adults[9]

- Face is more rounded, with softer features

- Smaller waist

- Upper arms approximately 2 cm longer, on average, for a given height[10]

- Changed distribution in weight and fat; more subcutaneous fat and fat deposits, mainly around the buttocks, thighs, and hips

- Labia minora, the inner lips of the vulva, may grow more prominent and undergo changes in color with the increased stimulation related with higher levels of estrogen.[11]

Males

In males, testosterone directly increases size and mass of muscles, vocal cords, and bones, deepening the voice, and changing the shape of the face and skeleton. Converted into DHT in the skin, it accelerates growth of androgen-responsive facial and body hair but may slow and eventually stop the growth of head hair. Taller stature is largely a result of later puberty and slower epiphyseal fusion.

- Growth of body hair, including underarm, abdominal, chest hair and pubic hair. Loss of scalp hair due to androgenic alopecia can also occur.

- Greater mass of thigh muscles in front of the femur, rather than behind it (as is typical in mature females)

- Growth of facial hair

- Enlargement of larynx (Adam's apple) and deepening of voice[12]

- Increased stature; adult males are taller than adult females, on average

- Heavier skull and bone structure

- Increased muscle mass and strength

- Hands, feet and nose grow larger

- Larger bodies

- Face is square, with more angular features

- Small waist, but wider than females

- Broadening of shoulders and chest; shoulders wider than hips[7]

- Increased secretions of oil and sweat glands[12]

- Coarsening or rigidity of skin texture due to less subcutaneous fat

- Higher waist-to-hip ratio than prepubescent or adult females or prepubescent males, on average

- Lower body fat percentage than prepubescent or adult females or prepubescent males, on average

References

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1871) The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex John Murray, London

- ↑ Weatherhead PJ, Robertson RJ (Feb 1979). "Offspring quality and the polygyny threshold: "The sexy son hypothesis"". American Naturalist. 113 (2): 201–208. doi:10.1086/283379.

- ↑ Lim, Matthew L. M., and Daiqin Li. "Courtship and Male-Male Agonistic Behaviour of Comsophasis Umbratica Simon, an Ornate Jumping Spider (Araneae: Salticidae)." The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology (2004): 52(2): 435-448. National University of Singapore. 20 September 2015

- ↑ G. Raspé (22 October 2013). Hormones and Embryonic Development: Advances in the Biosciences. Elsevier Science. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-4831-5171-7.

The first genetic male child with a defect in 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-steroid oxidoreductase to have reached puberty has been reported to have a high level of 3β-hydroxy-A5 steroid excretion, hypospadias at birth, salt-wasting, and a history of two siblings with congenital adrenal hyperplasia and ambiguous genitalia [33]. Although at puberty he has signs of virilization, he has developed pronounced gynecomastia. Thus, this boy demonstrates that breast development may occur in postpubertal males if the programing of the pubertal sex differentiation of the mammary gland anlagen is disturbed by an enzyme defect which causes a failure of fetal testicular testosterone production. This observation is completely consistent with the findings in the experimental models [11, 32].

- ↑ Neumann F, Elger W (March 1967). "Steroidal stimulation of mammary glands in prenatally feminized male rats". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1 (2): 120–3. PMID 6070056.

When administered to gravid rats during pregnancy an anti-androgenic steroid [cyproterone acetate] induced development of nipples in male fetuses. These nipples and associated glandular tissues develop after birth as in normal female animals. Progestin-estrogen treatment of adult, castrated feminized males produced stimulation of the glandular tissue similar to that seen after treatment of castrated female animals. In castrated male rats this treatment produces little glandular proliferation. It is concluded that androgens normally prevent the development of nipples and extensive formation of mammary tissue in male fetuses.

- ↑ Rajendran KG, Shah PN, Dubey AK, Bagli NP (1977). "Mammary gland differentiation in adult male rat--effect of prenatal exposure to cyproterone acetate". Endocr Res Commun. 4 (5): 267–74. PMID 608453.

Breast tissue of adult male Holtzman rats exposed to cyproterone acetate during embryonic differentiation showed presence of specific estradiol receptor proteins and C-19 steroid aromatase. We reported similar findings in gynecomastia in man. It is therefore proposed that gynecomastia probably results from failure of adequate testosterone action on the breast primordia during embryonic differentiation.

- 1 2 "Secondary Characteristics". hu-berlin.de. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- ↑ "Sexual Maturity". Technical Issues in Reproductive Health. Columbia University. May 2, 2008.

- ↑ Amis AA, Miller JH (Dec 1982). "The elbow". Clinics in rheumatic diseases. 8 (3): 571–93. PMID 7184689.

- ↑ Manwatching: A Field Guide to Human Behaviour, 1977, Desmond Morris

- ↑ Lloyd, Jillian (May 2005). "Female genital appearance: 'normality' unfolds". British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 12 (5): 643–646. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00517.x.

- 1 2 Sexual reproduction Archived 2009-02-08 at the Wayback Machine.