Scratch (programming language)

| |

| Paradigm | Event-driven, block-based programming language |

|---|---|

| Developer | MIT Media Lab Lifelong Kindergarten Group |

| First appeared |

2002 (first prototype). 2007 (public launch). 2013 (Scratch 2.0) |

| Typing discipline | Dynamic |

| Implementation language |

Squeak (Scratch 0.x, 1.x) ActionScript (Scratch 2.0) |

| OS | Windows, macOS, Linux |

| License | GPLv2 and Scratch Source Code License |

| Filename extensions |

.scratch (Scratch 0.x) .sb, .sprite (Scratch 1.x) .sb2, .sprite2 (Scratch 2.0+) |

| Website |

scratch |

| Major implementations | |

| Scratch | |

| Influenced by | |

| Logo, Smalltalk, HyperCard, StarLogo, AgentSheets, Etoys | |

| Influenced | |

| ScratchJr, Snap! | |

Scratch is a visual programming language and online community targeted primarily at children. Users of the site can create online projects using a block-like interface. The service is developed by the MIT Media Lab, and is translated into 70+ languages and is used in most parts of the world.[1] As of May 2018, there are more than 31,932,249 projects shared, 28,361,710 users registered, 156,310,759 comments posted, 4,533,610 studios created.[2]

Origin of name

Scratching is a technique used by disc jockeys to mix music clips together in creative ways and produce different sound effects by manipulating vinyl records on a turntable. Scratch takes its name from this technique, as it lets users mix together different media (including graphics, sound and other programs) in creative ways by "remixing" projects.[3][4]

Philosophy

Scratch encourages the sharing, reuse and combination of code, as indicated by their slogan, "Imagine, Program, Share"[5]. Users can make their own projects, or they may choose to "remix" someone else's project. Projects created and remixed with Scratch are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.[6] Scratch will automatically give credit to the user who created the original project and program.[3]

It is part of a research to design new technologies to enhance learning in after-school centers and other informal education settings, and broaden opportunities for youth who can possibly become designers and inventors. Scratch was developed based on ongoing interaction with youth and staff at Computer Clubhouses. The use of Scratch at Computer Clubhouses served as a model for other after-school centers demonstrating how informal learning settings can support the development of technological fluency, enabling young people to design and program projects that are meaningful to themselves and their communities.[7]

History

The MIT Media Lab's Lifelong Kindergarten group, led by Mitchel Resnick, in partnership with the Montreal-based consulting firm, the Playful Invention Company, co-founded by Brian Silverman and Paula Bonta, together developed the first desktop-only version of Scratch in 2003.

Scratch 2 was released on May 9, 2013.[8] With its introduction, custom blocks can be defined within projects.[9]

As of 2017, Scratch 2 is available online and as an application for Windows, macOS, Linux (Adobe Air required), and unofficially for Android as an APK file. The Scratch 2.0 Offline editor can be downloaded for Windows, Mac and Linux directly from Scratch's website. However, the unofficial mobile version must be downloaded from the Scratch forums.[10][11]

Scratch 3 has been released as a beta[12] and is available for use on most browsers, with the notable exception of Internet Explorer.[13] It features a language translation block, the stage 's presence on the right-hand side of the screen, and a fresher interface.

Educational use

Scratch was made popular in the United Kingdom through Code Clubs. Scratch is used as the introductory language because creation of interesting programs is relatively easy, and skills learned can be applied to other basic programming languages such as Python and Java.

Scratch is not exclusively for creating games. With the provided visuals, programmers can create animations, text, and more. There are already many programs which students can use to learn topics in math, history, and even photography. Scratch allows teachers to create conceptual and visual lessons and science lab assignments with animations that help visualize difficult concepts. Within the social sciences, instructors can create quizzes, games, and tutorials with interactive elements. Using Scratch allows young people to understand the logic of programming and how to creatively build and collaborate.[14] Scratch lets students create "meaningful personal as well as educational projects" which gives students a "practical tool" to express themselves after learning to use the language.[3]

Scratch is taught to more than 800 schools and 70 colleges of DAV organization in India and across the world.[15][16]

Harvard University lecturer Dr. David J. Malan prefers using Scratch over commonly used introductory programming languages, such as Java or C, in his introductory computer science course. However, there is a limited benefit in a college level education. Malan switched his course's language to C after the first week.[17][18]

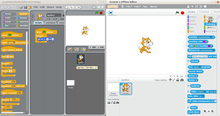

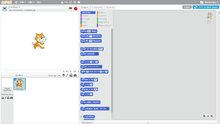

User interface

From left to right, in the upper left area of the screen, there is a stage area, featuring the results (i.e., animations, turtle graphics, etc., everything either in small or normal size, full-screen also available) and all sprites thumbnails listed in the bottom area. The stage uses x and y coordinates, with 0,0 being the stage center. The stage is 480 pixels wide, and 360 pixels tall, x:240 being the far right, x:-240 being the far left, y:180 being the top, and y:-180 being the bottom.[8]

There are many ways to create personal sprites and backgrounds. First, users can draw their own sprite manually with "Paint Editor" provided by Scratch.[8] Second, users can choose a Sprite from the Scratch library that contains default sprite, user's past creations, a picture using a camera, or clip art.[19]

With a sprite selected in the bottom-left area of the screen, blocks of commands can be applied to it by dragging them from the Blocks Palette onto the right area of the screen, containing all the scripts associated with the selected sprite. Under the Scripts tab, all available blocks are listed and categorized as the Motion, Looks, Sound, Pen, Data, Events, Control, Sensing, Operators, and More Blocks as shown in the table below. Each can also be individually tested under different conditions and parameters via double-click.

| Category | Notes | Category | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | Moves sprites, changes angles and changes X and Y values. | Events | Contains event handlers placed on the top of each group of blocks | |||

| Looks | Controls the visuals of the sprite; attach speech or thought bubble, change of background, enlarge or shrink, transparency, shade | Control | Conditional if-else statement, "forever", "repeat", and "stop" | |||

| Sound | Plays audio files and programmable sequences | Sensing | Sprites can interact with the surroundings the user has created | |||

| Pen | Draw on the canvas by controlling pen width, color, and shade. Allows for turtle graphics. | Operators | Mathematical operators, random number generator, and-or statement that compares sprite positions | |||

| Data | Variable and List usage and assignment | More Blocks | Custom procedures (blocks) and external devices control and can import from PicoBoard or Lego WeDo 1.0/2.0 | |||

Besides the Scripts tab, there are two additional tabs, the Costumes tab and the Sounds tab. An expandable bar at the right is Help area.

Next to the Scripts tab, there is the Costumes tab, where users can change the look of the sprite in order to create various effects, including animation.[8] And the last tab is the Sounds tab, where users insert sounds and music to a sprite.[19]

In comparison to the previous versions of Scratch, the areas have been rearranged in version 2.0, as previously the blocks palette was in the left area, the selected sprite area and scripts area associated with a selected sprite were in the middle of the screen, and the stage area with sprites thumbnails listed below it were in the right area of the screen.[20]

Community of users

Scratch is used in many different settings: schools,[21] museums,[22] libraries,[3] community centers, and homes. Although Scratch’s main user age group is 8–18 years of age, Scratch has also been created for educators and parents. This wide outreach has created many surrounding communities, both physical and digital.[23]

Online community

On Scratch, members have the capability to share their projects and get feedback. Projects can be uploaded directly from the development environment to the Scratch website and any member of the community can download the full source code to study or to remix into new projects.[24][25] Members can also create project studios, comment, tag, favorite, and "love" others' projects, follow other members to see their projects and activity, and share ideas. Projects range from games to animations to practical tools. Additionally, to encourage creation and sharing amongst users, the website frequently establishes "Scratch Design Studio" challenges.[26]

The MIT Scratch Team ensures that this community maintains a friendly and respectful environment for people of all ages, races, ethnicities, religions, sexual orientations, and gender identities. All members are asked to provide feedback constructively and report any content that does not follow the community guidelines. To further ensure this community, the Scratch Team manages site activity and responds to reports on a daily basis.[27][28]

There is also an online community for educators, called ScratchEd. ScratchEd was developed and supported by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. In this community, Scratch educators share stories, exchange resources, ask questions, and find people.[29]

Scratch Wiki

The Scratch Wiki is a medium-sized wiki for the Scratch educational programming language and its website, history, and phenomena surrounding it. The wiki is supported by the Scratch Team (developers of Scratch), but is primarily written by Scratchers (users of Scratch) for information regarding projects and things interesting users.[30]

Events

Scratch Educators can gather in person at Scratch Educator Meetups. At these gatherings, Scratch Educators learn from each other and share ideas and strategies that support computational creativity.[31]

An annual "Scratch Day" is declared in May each year. Community members are encouraged to host an event on or around this day, large or small, that celebrates Scratch. These events are held worldwide, and a listing can be found on the Scratch Day website.[32]

Features and derivatives

Scratch uses event-driven programming with multiple active objects called sprites.[8] Sprites can be drawn, as vector or bitmap graphics, from scratch in a simple editor that is part of Scratch, or can be imported from external sources.

The current version of Scratch does not treat procedures as first class structures and has limited file I/O options with Scratch 2.0 Extension Protocol; an experimental extension feature that allows interaction between Scratch 2.0 and other programs.[33] The Extension protocol allows interfacing with hardware boards such as Lego Mindstorms[34] or Arduino.[35] In addition Scratch 2 only supports one-dimensional arrays, known as "lists". Floating point scalars and strings are supported as of version 1.4, but with limited string manipulation ability. There is a strong contrast between the powerful multimedia functions and multi-threaded programming style and the rather limited scope of the Scratch programming language. On May 6, 2013, Scratch closed for 3 days to update to Scratch 2.0. The update changed the look of the site and included an online project editor. An offline Scratch 2 Editor is currently available.[36]

A number of Scratch derivatives[37] called Scratch Modifications have been created using the source code of Scratch version 1.4. These programs are a variant of Scratch that normally include a few extra blocks[38] or changes to the GUI.

In July 2014, a program called ScratchJr was released for iPad. In 2016, ScratchJr was developed for android. Although it was heavily inspired by Scratch and co-led by Mitch Resnick, the original creator of Scratch, it is nonetheless a complete rewrite designed for younger children.[39]

Some modifications additionally introduce shifts in underlying approach to computing, such as the language Snap!, featuring first class procedures (their mathematical foundations are called also lambda calculus), first class lists (including lists of lists), and first class truly object oriented sprites with prototyping inheritance, and nestable sprites, which are not part of Scratch.[40] Snap! (its previous version was called BYOB) was developed by Jens Mönig[41][42] with documentation provided by Brian Harvey[43][44] from University of California, Berkeley and has been used to teach "The Beauty and Joy of Computing" introductory course in CS for non-CS-major students.[45]

The source-code of Scratch and its derivatives are based on Squeak, which is based on Smalltalk-80. Version 2 of Scratch is implemented in ActionScript, with an experimental JavaScript-based interpreter being developed in parallel.[46]

See also

The following youth computing projects also originated in the MIT Lifelong Kindergarten Group:

See also:

- AgentCubes

- AgentSheets

- Alice (software)

- Blockly, the snap-together block language used at Code.org

- Etoys

- Greenfoot

- mBlock - graphical programming environment based on Scratch

- Microsoft Kodu Game Lab

- Microsoft Small Basic

- Verge3D offers a similar scripting environment for WebGL applications (dubbed Puzzles).[47]

References

- ↑ "Scratch - Imagine, Program, Share". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "Scratch - Imagine, Program, Share". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Lamb, Annette; Johnson, Larry (April 2011). "Scratch: Computer Programming for 21st Century Learners". Teacher Librarian. 38 (4): 64–68. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Schorow, Stephanie (14 May 2007). "Creating from Scratch". MIT News Office. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "Scratch - Imagine, Program, Share". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "Remix - Scratch Wiki". wiki.scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ↑ Resnick, Mitchel. "A Networked, Media-Rich Programming Environment to Enhance Informal Learning and Technological Fluency at Community Technology Centers". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marji, Majed (2014). Learn to Program with Scratch. San Francisco, California: No Starch Press. pp. xvii, 1–9, 13–15. ISBN 9781593275433.

- ↑ Kids’ Programming Tool Scratch Now Runs In The Browser Archived 2017-07-09 at the Wayback Machine., TechCrunch, May 2013.

- ↑ "Updated Scratch 2.0 Offline (Beta) is now available!". Scratch. 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Scratch 20 Preview". YouTube. MITScratchTeam. 1 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Scratch 3.0 GUI". beta.scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "Scratch - Scratch 3.0 FAQ". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ Martin, Neil (25 June 2015). "What is Scratch? Is it AV or IT?". AV Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ "DAV CS Syllabus" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ↑ "DAV Jharkhand Syllabus". Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ↑ Young, Jeffrey R. (July 20, 2007). "Fun, Not Fear, Is at the Heart of Scratch, a New Programming Language". The Chronicle of Higher Education. ISSN 0009-5982. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ↑ "CS50 Syllabus". Archived from the original on 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2015-05-17.

- 1 2 "Science Buddies: Scratch User Guide: Installing & Getting Started with Scratch". www.sciencebuddies.org. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ↑ Resnick, Mitchel; Maloney, John; Hernández, Andrés; Rusk, Natalie; Eastmond, Evelyn; Brennan, Karen; Millner, Amon; Rosenbaum, Eric; Silver, Jay; Silverman, Brian; Kafai, Yasmin (November 2009). "Scratch: Programming for All". Communications of the ACM. 52 (11): 60–67. doi:10.1145/1592761.1592779.

- ↑ "Canadian schools starting to teach computer coding to kids". CTV.ca. 2014-04-30. Archived from the original on 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "Scratch Day". Science Museum of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Scratch statistics". Scratch. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ↑ Monroy-Hernandez, Andres; Hill, Benjamin Mako; Gonzalez-Rivero, Jazmin; Boyd, Danah (2011). "Computers Can't Give Credit: How Automatic Attribution Falls Short in an Online Remixing Community". Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '11). ACM. pp. 3421–30. arXiv:1507.01285. doi:10.1145/1978942.1979452.

- ↑ Hill, B.M; Monroy-Hernández, A.; Olson, K.R. (2010). "Responses to remixing on a social media sharing website". ICWSM 2010 : Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, May 23–26, 2010. Washington, D.C.: AAAI Press. arXiv:1507.01284. Bibcode:2015arXiv150701284M. ISBN 9781577354451. OCLC 844857775.

- ↑ "Scratch Design Studio - Scratch Wiki". wiki.scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "Scratch - Imagine, Program, Share". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "Scratch - Scratch Community Guidelines". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "Scratch - Educators". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "Scratch - Imagine, Program, Share". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "ScratchEd | Meetup Pro". www.meetup.com. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "May 14 2016 Scratch Day". Scratch Day. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ↑ "Scratch Extension Protocol (2.0)". MIT. Archived from the original on 2016-04-21.

- ↑ "EV3+Scratch Extension". Scratch extension GitHub. Code & Circuit. Archived from the original on 2016-01-20.

- ↑ "Preliminary Scratch extension for talking to Arduino boards running Firmata". Scratch extension GitHub. Damellis. Archived from the original on 2018-01-16.

- ↑ "Scratch - Scratch Offline Editor". scratch.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "Scratch Modification". Scratch Wiki. Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the MIT Media Lab. Archived from the original on 2013-09-23.

- ↑ "Blocks". Scratch Wiki. Archived from the original on 2011-09-02.

- ↑ "ScratchJr - About". www.scratchjr.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ↑ "Snap! (Build Your Own Blocks) 4.0". BYOB homepage. University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Mönig, Jens (June 2007). "Jens on Scratch". Scratch. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Mönig's blog post announcing BYOB as bringing protypal inheritance to Scratch". Chirp. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "HomePage for Brian Harvey". Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ Harvey, Brian (July 2008). "Brian Harvey user contributions page". Scratch. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Beauty and Joy of Computing course homepage". EECS Instructional Support Group Home Page. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "We're seeking contributors to help finish our HTML5 Scratch player (now open sourced!)". Scratch. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Verge3D". Soft8Soft.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Scratch |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scratch (programming language). |

- Official website

- Scratch at Curlie (based on DMOZ)