Sarah Wool Moore

| Sarah Wool Moore | |

|---|---|

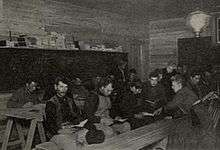

Immigrant camp school house at Ashokan dam established by Sarah Wool Moore | |

| Born |

May 3, 1846 Plattsburgh, Clinton County, New York |

| Died |

May 19, 1911 (aged 65) Valhalla, Westchester County, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | teacher |

| Years active | 1866–1911 |

| Known for | founding the Nebraska Art Association and the New York Society for Italian Immigrants |

Sarah Wool Moore (1846–1911) was an artist and art teacher, as well as a language instructor, who was the first director of the Art Department at the University of Nebraska and founded the Nebraska Art Association. After leaving Nebraska, she taught in New York City. Disturbed by the intolerance shown to Italian immigrants, Moore worked as secretary of the New York Society for Italian Immigrants. In that capacity, she founded and taught at several language schools in New York and Pennsylvania to facilitate Italian immigrants learning of English. She also wrote English-Italian handbooks to help immigrants quickly learn the language they would use on a daily basis.

Early life

Sarah Wool Moore was born on May 3, 1846 in Plattsburgh, Clinton County, New York[1] to Charotte Elizabeth (née Mooers) and Amasa Corbin Moore.[2][3] Her family were some of the most prominent citizens in Clinton County. Her father was an attorney, her paternal grandfather, Pliny Moore, had been a judge and was the first permanent settler of Champlain, New York.[3][4] He had originally been from Sheffield, Massachusetts and served in the American Revolutionary War. Pliny's wife, Mary Corbin,[5] was the daughter of Captain John Corbin who had come to the area from Connecticut.[6] Moore was the maternal granddaughter of Hannah (née Platt)[7] and Benjamin Mooers,[2][8] who was the founder of Beekmantown, New York. He was also the first sheriff of Clinton County and served as country treasurer for forty-two years. He served as an Assemblyman in the New York State Assembly for four terms and in the Senate for one term. He was a Major General in the War of 1812 and commanded the New York Militia at the Battle of Plattsburgh.[9]

Moore grew up as one of ten children in the home known as General Mooer's House, which is now recognized with a New York State Historic Marker.[10] She was the next to the youngest child in the family, but became the youngest child when her brother Arthur died just prior to his seventh birthday.[11] She attended Packer Collegiate Institute, graduating in 1865.[1]

Career

For a decade she taught art and then between 1875 and 1884, Moore furthered her own education, traveling in Europe and studying for five years at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna under the tutelage of August Eisenmenger. She returned to the United States and in 1884 became the head of the art department at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. In addition to directing the department, she lectured on art history, drawing and painting.[1] When she was hired, the art department was under the Agricultural Division of the Industrial College and Moore struggled to gain recognition for the department. Because the school did not authorize a fine arts college until 1912,[12] the art and music teachers had to charge their students for classes.[13] In 1888, Moore founded the Hayden Art Club, which would become the Nebraska Art Association, pioneering the art movement in the state.[14][15] Resigning in 1892, she returned to New York,[1] after presenting regent Charles Gere, founder of the Nebraska State Journal, with a portrait she had painted of him.[16][17] In 1898, Moore began giving art classes and lectures in Brooklyn.[18]

In 1900, Moore was the driving force in founding the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants (often called the Society for Italian Immigrants), which originally had goals to facilitate new Italian immigrants in their assimilation to a new country and help them navigate among steerers and labor bosses who wanted to profit off of their labor.[19][20] These grifters recommended boarding houses or jobs in which they got kickbacks for placing boarders or workers. To combat them, Moore and other social workers for immigrants made lists of honest boarding houses and employers. They hired agents to meet immigrants' ships to avoid con men.[20] Quickly, Moore recognized that without language skills, workers being hired in large numbers for infrastructure projects were at a disadvantage and needed to quickly learn the language of their new home. As secretary of the organization, Moore pressed for the development of schools in the labor camps.[19][21][22] Her focus was on adult education and her innovative approach did not teach language in the same way that schools typically taught children.[23]

In 1902, Moore published an English-Italian reader to assist immigrants in learning English.[24] The book was described as a useful handbook to teach immigrants language they would need in their business dealings and daily lives.[21] In 1905, she began a school at the Aspinwall labor camp, where laborers were working at the filtration plant. Teaching night courses to help the immigrant population learn English, as well as rudimentary writing, arithmetic and geography, Moore appealed to the state legislature for government funding to cover the costs of teaching.[25][26] In the mean time, she led a campaign speaking at various churches and YWCA facilities to enlist both volunteers to assist with the teaching and make donations to support the schools.[27] A bill was presented to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1907 to authorize schools for labor camp workers if they made application to the local school boards for night classes.[28] Expanding from the program developed for Aspinwall, Moore opened schools in the work camps at the Stoneco quarry in 1907; at Wappingers Falls; at Brown's Station, New York for the Ashokan Reservoir; and in Valhalla for workers at the Kensico Reservoir.[29][26][30][31] In 1907, Wool was given a commendation for her work in establishing schools by the Commissioner of Emigration for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Society for Italian Immigrants was recognized with an honorary award for assisting immigrants.[32]

Death and legacy

Moore died on May 19, 1911 in Valhalla, New York.[29] In 1953, the Frank M. Hall Collection of contemporary art was shown at the University of Nebraska Galleries in Morrill Hall. The collection, known as one of the largest collections of American contemporary art owned by a university at that time, had begun when Moore taught a painting class to Anna Reed Hall and sparked her interest in collecting.[33] Her work in the labor camps, inspired women's groups in Canada to propose similar educational facilities be established for their workers[22] and in Pennsylvania, the bill that she urged appropriated $100,000 to establish 200 work camp schools for immigrants of various nationalities.[34]

Works

- Perrot, George; Moore, Sarah Wool (translator) (1900). Art history in the high school. Syracuse, New York: C. W. Bardeen. OCLC 16055376.

- Moore, Sarah Wool (November 10, 1901). "Must Help Italians Along". Brooklyn, New York: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 14. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Moore, Sarah Wool (1902). An Illustrated English-Italian Language Book and Reader. Boston, Massachusetts: D.C. Heath & Company. OCLC 894204498.

- Moore, Sarah W. (March 1907). "Near Recollections: Notes on Camp School, No. 1, Aspinwall, Pennsylvania". The Survey. East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Survey Associates for the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. 17: 894–902.

- Moore, Sarah Wool (1908). Libro illustrato di lingua inglese: an illustrated English-Italian language book and reader. Boston, Massachusetts: D.C. Heath & Company. OCLC 30106548.

- Moore, Sarah Wool (June 4, 1910). "The Teaching of Foreigners". The Survey. East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Survey Associates for the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. 24: 386–392.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Willard & Livermore 1893, p. 517.

- 1 2 The Burlington Free Press 1909, p. 5.

- 1 2 Tuttle 1909, p. 29.

- ↑ Hurd 1880, p. 117.

- ↑ Hurd 1880, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Hurd 1880, p. 260.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution 1907, p. 148.

- ↑ Tuttle 1909, p. 66.

- ↑ Hurd 1880, p. 237.

- ↑ The Chazen Companies 2010, p. 81.

- ↑ Moore 1903, pp. 82–84.

- ↑ Kinsey 1995, p. 265.

- ↑ The Catalogue 1889, p. 87.

- ↑ Brush and Pencil 1903, p. 469.

- ↑ The Lincoln Evening Journal 1926, p. 11.

- ↑ Lincoln Daily News 1892, p. 5.

- ↑ University of Nebraska–Lincoln 2005.

- ↑ The Courier 1898, p. 6.

- 1 2 Iorizzo & Mondello 1971, p. 100.

- 1 2 Baily 1999, p. 207.

- 1 2 Harris 1902, pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 The Daily Colonist 1911, p. 8.

- ↑ Claghorn 1914, p. 267.

- ↑ The Florida Star 1902, p. 8.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Press 1906, p. 17.

- 1 2 McDonald 1915, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ The Gazette Times 1906, p. 10.

- ↑ The New York Tribune 1907, p. 56.

- 1 2 The New York Times 1911, p. 19.

- ↑ Musso 2012, pp. 1B-2B.

- ↑ Fogelsonger 1911, pp. 688–689.

- ↑ Bollettino dell'Emigrazione 1907, pp. 281–282.

- ↑ The Lincoln Star 1953, p. 32.

- ↑ Hall 1907, pp. 892–893.

Bibliography

- Baily, Samuel L. (1999). Immigrants in the Lands of Promise: Italians in Buenos Aires and New York City, 1870 – 1914. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3562-5.

- Chazen Engineering, Land Surveying & Landscape Architects Company (December 2010). "Town of Plattsburgh Comprehensive Plan" (PDF). Town of Plattsburgh. Plattsburgh, New York: Plattsburgh Town Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Claghorn, Kate Holladay (December 5, 1914). "Book Reviews". The Survey. East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Survey Associates for the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. 33: 265–267.

- Daughters of the American Revolution (1907). Lineage book. 63. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Publishing Company.

- Fogelsonger, H. M. (July 18, 1911). "Recent Social Progress". The Inglenook. Elgin, Illinois: Brethren Publishing House. 13 (29): 687–689, 710. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- Hall, Robert C. (March 1907). "Camp Schools and the State". The Survey. East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Survey Associates for the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. 17: 892–893.

- Harris, Sarah B (May 31, 1902). "Observations". Lincoln, Nebraska: The Courier. p. 2. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hurd, Duane Hamilton (1880). History of Clinton and Franklin Counties, New York: with illustrations and biographical sketches of its prominent men and pioneers. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J.W. Lewis & Company. OCLC 5692695869.

- Iorizzo, Luciano J.; Mondello, Salvatore (1971). The Italian-Americans. New York City: Twayne Publishers.

- Kinsey, Joni L. (1995). "IX. Cultivating the Grasslands: Women Painters in the Great Plains". In Trenton, Patricia. Independent Spirits: Women Painters of the American West, 1890–1945. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 243–273. ISBN 978-0-520-20203-0.

- McDonald, Robert Alexander Fyfe (1915). Adjustment of School Organization to Various Population Groups. Contributions to Education. 75. New York City: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Ministero Degli Affari Esteri Commissariato dell'Emigrzione (1907). "Diploma d'onore" [Honorary Award]. Bollettino dell'Emigrazione (in Italian). Rome, Italy: Tipografia Nazionale de G. Bertero E. C. Via Umbria (18). Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Moore, Horace Ladd (1903). Andrew Moore of Poquonock and Windsor, Conn., and his descendants. Lawrence, Kansas: Journal Publishing Co. OCLC 11388762.

- Musso, Anthony P. (April 11, 2012). "Community was home to quarry workers" (PDF). Poughkeepsie, New York: The Poughkeepsie Journal. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- Tuttle, Maria Jeannette Brookings (1909). Three centuries in Champlain valley; a collection of historical facts and incidents. Plattsburgh, New York: Saranac chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. OCLC 670380102.

- Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice, eds. (1893). A woman of the century; fourteen hundred-seventy biographical sketches accompanied by portraits of leading American women in all walks of life. Buffalo, New York: Charles Wells Moulton. OCLC 751955051.

- "Art Association Accepts Paintings". Lincoln, Nebraska: The Lincoln Evening Journal. January 2, 1926. p. 11. Retrieved January 30, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Camp Schools: Teaching Italian Laborers to Read". New York City: The New York Tribune. February 17, 1907. p. 56. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Clubs". The Gazette Times. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. November 21, 1906. p. 10. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dinner to MacDonough". Burlington, Vermont: The Burlington Free Press. August 13, 1909. p. 5. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Gleanings from American Art Centers". Brush and Pencil. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Frick Collection, and the Brooklyn Museum. 11 (6): 465–473. March 1903. ISSN 1932-7080. JSTOR 25505875.

- "Hall Collection on 25th Anniversary to be Shown in Entirety at Morrill Hall". Lincoln, Nebraska: The Lincoln Star. October 4, 1953. p. 32. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Indian River Ripples". Titusville, Florida: The Florida Star. May 9, 1902. p. 8. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Library (Old)". Historic Buildings. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska–Lincoln. 2005. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "Moore, Sarah Wool". New York City: The New York Times. May 21, 1911. p. 19. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "More Schools for Italians". Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pittsburgh Press. June 10, 1906. p. 17. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "School of the Fine Arts". The Catalogue. Lincoln, Nebraska: The University of Nebraska: 87–88. 1889. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Teaching Foreigners". Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: The Daily Colonist. July 25, 1911. p. 8. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "(untitled)". Lincoln, Nebraska: Lincoln Daily News. November 12, 1892. p. 5. Retrieved January 30, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "(untitled)". Lincoln, Nebraska: The Courier. December 3, 1898. p. 6. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.