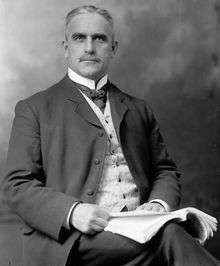

Sam Hughes

| The Honourable Sir Samuel Hughes KCB PC | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Militia and Defence | |

|

In office 10 October 1911 – 12 October 1916 | |

| Prime Minister | Robert Laird Borden |

| Preceded by | Frederick William Borden |

| Succeeded by | Albert Edward Kemp |

| Member of Parliament for Victoria North | |

|

In office 11 February 1892 – 2 November 1904 | |

| Preceded by | John Augustus Barron |

| Succeeded by | none |

| Member of Parliament for Victoria | |

|

In office 3 November 1904 – 24 August 1921 | |

| Preceded by | none |

| Succeeded by | John Jabez Thurston |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

January 8, 1853 Darlington, Canada West |

| Died |

August 24, 1921 (aged 68) Lindsay, Ontario, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Political party | Unionist |

| Other political affiliations | Liberal-Conservative |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Burk |

| Alma mater | Toronto Normal School, University of Toronto |

| Profession | Teacher, editor |

Sir Samuel Hughes, KCB PC (January 8, 1853 – August 23, 1921) was the Canadian Minister of Militia and Defence during World War I. He was notable for being the last Liberal-Conservative cabinet minister, until he was dismissed from his cabinet post.

Early life

Hughes was born January 8, 1853, at Solina near Bowmanville in what was then Canada West. He was a son of John Hughes from Tyrone, Ireland, and Caroline (Laughlin) Hughes, a Canadian descended from Huguenots and Ulster Scots.[1] He was educated in Durham County and later attended the Toronto Normal School and the University of Toronto. In 1866 he joined the 45th West Durham Battalion of Infantry and fought against the Fenian raids in the 1860s and 1870s.[2] He later claimed, in the British Who's Who, to have "personally offered to raise" Canadian contingents for service in "the Egyptian and Sudanese campaigns, the Afghan Frontier War, and the Transvaal War".[3]

He was a teacher from 1875 to 1885, when he moved his family to Lindsay, where he had bought The Victoria Warder, the local newspaper. He was the paper's publisher from 1885 to 1897.

Member of Parliament

He was elected to Parliament in 1892. The Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier had declared his support for the British policies in South Africa, but was non-committal about sending Canadian troops if war should break out.[4] In the summer of 1899, the Governor General of Canada, Lord Minto, and the commander of the Canadian Militia, Colonel Edward Hutton, drafted a secret plan for a Canadian contingent of twelve hundred men to go to South Africa, and decided that Hughes as one of the most outspokenly imperialist Members of Parliament was to be one of the commanders. In September 1899, Minto and Hutton first informed Frederick William Borden, the Minister of Militia and Defence, of the plan that they had drafted, through Laurier remained out of the loop.[4] As Laurier continued to hesitate, Hughes offered to raise a regiment at his own expense to fight in South Africa, an offer which threatened to upset Hutton's plans as Hughes's offer gave Laurier the perfect excuse for doing nothing.[5] When Hutton ordered Hughes as an militia officer to remain silent, Hughes responded with an angry outburst in public about the attempt of a British officer to silence a Canadian MP, creating what the Canadian historian Desmond Morton called a clash of "two like-minded, but out-sized egos".[5]

Boer War service

On 3 October 1899, the Transvaal Republic declared war on Great Britain.[5] The Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joseph Chamberlain, sent Laurier a note thanking him for his offer of Canadian troops to South Africa, which confused the prime minister as he made no such offer.[5] At the same time the October 1899 edition of the Canadian Military Gazette published the details of the plan to sent 1200 men to South Africa.[5] When Laurier denied in the House of Commons having any plans to sent troops to South Africa, Chamberlain's note was leaked to the press, and on 9 October 1899, Laurier received a note from editor of the Toronto Globe (which supported the Liberals) saying the prime minister must "either send troops or get out of office".[5] As the Liberal caucus was badly divided between French-Canadian MPs opposed to the Boer War and English-Canadian MPs for the Boer War, Laurier did not dare summon Parliament for a vote as the Liberals might split over the issue, and instead issued an order-in-council on 14 October saying that that Canada would provide a force of volunteers for South Africa.[6] Hughes promptly volunteered to serve in South Africa, but was vetoed by Hutton who neither forgotten nor forgiven Hughes for his insubordination and his abrasive refusal to be silenced.[7] However, perhaps as a form of revenge against Hutton, Laurier insisted that Hughes be allowed to go to South Africa.[7]

Hughes fought in the Second Boer War in 1899 after helping to convince Sir Wilfrid Laurier to send Canadian troops. Upon boarding the ship SS Sardinian which left Quebec City for Cape Town on 31 October carrying 1, 061 Canadian volunteers, Hughes announced that he was free of all military authority and would take no orders from any officer.[7] Upon arriving in South Africa, Hughes told the press that the Boers "on their old plugs of horses" would out-ride the British on the veld, a remark that marked the beginning of Hughes's stormy service in South Africa as ironically the ultra-imperialist Hughes constantly clashed with the British Army.[8] Hughes developed a strong contempt for the British military while in South Africa and came away with the idea that frontier living had made the Canadians tougher and hardier soldiers than the British. The Canadian historian Pierre Berton wrote that Hughes "hated the British Army".[9] Hughes always believed the part-time citizen soldiers of the Canadian militia were far better soldiers than the full-time professionals of the British Army, a viewpoint that did much to influence his decisions in World War I.[9] It also during the Boer War that Hughes become convinced of the thesis that the Ross rifle developed by a Scottish sportsman, Sir Charles Ross, and manufactured in Canada was the ideal weapon for infantrymen.[10] The more that the British Army rejected the Ross rifle as unsuitable, the more it persuaded Hughes of its superiority, through Morton noted that the British objections to the Ross rifle were sound as the Ross rifle was a hunting rifle that overheated after rapid firing and was too easily jammed by dirt.[10]

Hughes would continually campaign, unsuccessfully, to be awarded a Victoria Cross for actions that he had supposedly taken in the fighting. The Canadian historian René Chartrand wrote that "...Hughes's character may be read from the fact that he had actually asked for the Victoria Cross for his services in South Africa", which was most unorthodox as normally one has to be recommended for the Victoria Cross.[11] Hughes published most of his own accounts of the war. Hughes often said that when he left, the British commander was "sobbing like a child." In fact, Hughes was dismissed from Boer War service in the summer of 1900 for military indiscipline, and sent back to Canada.[12] Letters in which Hughes charged the British military with incompetence had been published in Canada and South Africa. Hughes had also flagrantly disobeyed orders in a key operation by granting favourable terms to an enemy force which surrendered to him. Although Hughes had proved a competent, and sometimes exceptional, front-line officer, boastfulness and impatience told strongly against him.[13] Hughes's demand for a Victoria Cross was refused, but as a consolation prize, his demand for to be knighted for his Boer War services was granted, albeit only in 1915, and therefore Hughes was proud to be known as "Sir Sam".[14] By this time, Hughes had become convinced that he deserved not one, but two two Victoria Crosses for his service in South Africa, a demand that exasperated the War Office in London who patiently told Hughes one cannot recommend oneself for the Victoria Cross, and his requests for two Victoria Crosses could not be considered.[9]

Hughes, who claimed to have been offered but declined the post of Deputy Minister of Militia in 1891,[3] was appointed Minister of Militia after the election of Robert Laird Borden in 1911, with the aim of creating a distinct Canadian army within the British Empire, to be used in case of war. He wrote a letter to the Governor General, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, about his longtime demand for the Victoria Cross. Connaught privately recommended that Borden get rid of him. Chartrand described Hughes as an individual endowed with "great charm, wit, and driving energy, allied with consummate political skills", but on the negative side called him "a stubborn, pompous racist" and a "passionate Orange Order supremacist" who did little to disguise his dislike of Catholics in general and of French-Canadians in particular.[14] Hughes's views later did much to put off French-Canadians and Irish-Canadians from supporting the war effort in World War I.[14] Chartrand further wrote that Hughes was a megalomaniac with a grotesquely inflated sense of his own importance who "would admit no contradiction to his views".[14] Hughes's own son, Garnet, wrote: "God help he who goes against my father's will".[14]

Minister of Militia and Defence

Borden had "profound misgivings" about appointing Hughes to the cabinet, but as Hughes insisted on the defense portfolio, and Borden owned Hughes a political debt for his past loyalty, he received his wish to be appointed defense minister.[15] Hughes was a colonel in the militia, and he insisted on wearing his uniform at all times, including cabinet meetings.[15] In 1912, Hughes promoted himself to the rank of major-general.[16] An energetic minister, Hughes traveled all over Canada in his private luxury railroad car to attend parades and manoeuvres by the militia.[17] Hughes's penchant for colorful and flamboyant statements made him a media favorite, and journalists were always asking the defense minister for his opinions on any subject, secure in the knowledge that Hughes was likely to say something outrageous that would help to sell newspapers.[15] Berton described Hughes as a "...a staunch Britisher, but also a staunch Canadian nationalist, who was absolutely determined that Canada should not be a vassal of the mother country".[18] Hughes saw the Dominions as equal partners of the United Kingdom in the management of the British empire, making claims for powers for Ottawa that anticipated that 1931 Statute of Westminster, and fiercely fought against attempts on the part of London to treat Canada in a mere colonial role.[9]

In December 1911, Hughes announced that he was going to increase the militia budget and built more camps and drill halls for the militia.[15] From 1911 to 1914, the defense budget rose from $7 million per year to $11 million per year.[15] Hughes was openly hostile to the Permanent Force Militia as Canada's small professional army was known, and praised the Non-Permanent Force Militia as reflecting the authentic fighting spirit of Canada.[15] Taking the view that citizen soldiers were better soldiers than the professional soldiers, Hughes cut spending on the "bar room loafers" as he called the Permanent Force Militia to increase the size of the Non-Permanent Force.[15] Critics charged that Hughes favored the Non-Permanent Force Militia as it allowed him opportunities for patronage as he gave various friends and allies officers' commissions in the non-permanent force militia that did not exist with the Permanent Force, where promotion was based on merit.[17]

In April 1912, Hughes caused much controversy when he forbade militia regiments in Quebec from taking part in Catholic processions, a practice that went back to the days of New France, and had been tolerated under British rule and since 1867 under Confederation.[19] Hughes justified the move as upholding secularism, but Quebec newspapers noted that Hughes was an Orangeman, and blamed his decision as due to the anti-Catholic prejudices one could expect from a member of the Loyal Orange Order.[19] Hughes's practice of pushing out experienced Permanent Force officers serving on the general staff in favor of Non-permanent Force officers and his lavish spending were also the causes of controversy.[19] Hughes used the Defense Department funds to give a free Ford Model T car to every militia colonel in Canada, a move which caused much criticism.[19] In 1913, Hughes went on an all-expenses paid junket to Europe together with his family, his secretaries, and various militia colonels who were his friends and their families.[19] Hughes justified the trip, which lasted several months, as necessary to observe military manoeuvres in Britain, France and Switzerland, but to many Canadians, it appeared more like an expensive vacation taken with the taxpayer's money.[19]

Hughes's intention was to make militia service compulsory for every able-bodied male, a plan that caused considerable public opposition.[19] Chartrand wrote that Hughes's plan for compulsory militia service, based on the example of Switzerland, failed to take into account the differences between Switzerland, a highly conformist society in Central Europe vs. Canada, a more individualistic society in North America.[14] The reasons Hughes gave for a larger Swiss-style militia were moral, not military.[17] A strong believer in temperance, Hughes banned alcohol from militia camps and believed that compulsory militia was the best way of stamping out the consumption of alcohol in Canada.[19] In a speech in Napanee in 1913, Hughes declared he wanted to :

"To make the youth of Canada self-controlled, erect, decent and patriotic through military and physical training, instead of growing up to as under present conditions of no control, into young ruffians or young gadabouts; to ensure peace by national preparedness for war;to make military camps and drill halls throughout Canada clean, wholesome, sober and attractive to boys and young men; to give that final touch to imperial unity, and crown the arch of responsible government by an inter-Imperial Parliament dealing only with Imperial affairs".[19]

Hughes's campaign for compulsory militia service as a form of moral reformation to save the alleged wayward young men of Canada from lives of debauchery and licentiousness made him into one of the better known and most controversial ministers in the Borden government.[20] Borden himself wanted to sack Hughes by 1913, whom he regarded as a political liability, but was afraid of his bellicose defense minister to whom he also owned some major political debts.[21] Borden was a gentlemanly and mild-mannered lawyer from Halifax who was intimidated by Hughes, a huge blustering and combative Orangeman overtly fond of getting into brawls, who wrote "long, vituperative letters" at the slightest criticism, claimed to be "loved by millions" of voters, and often compared himself to a train and his critics to dogs.[16] Hughes himself often said that Borden was "gentle hearted as a girl".[22]

First World War

_(cropped).jpg)

In 1839, a treaty had been signed by Prussia and Britain guaranteeing the independence and neutrality of Belgium. On 2 August 1914, Germany, which had assumed Prussia's commitment to Belgian neutrality and independence in 1871, invaded Belgium as the German chancellor Dr. Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg dismissed the guarantee as a "mere scrap of paper" and stated for the leaders of Germany "might was right". The question facing British leaders was whatever the United Kingdom would honor the guarantee of Belgium by declaring war on Germany or not. On the morning of 3 August 1914, Hughes arrived at the Defense Department, visibly upset and angry, and according to those present cried out: "They are going to skunk it! They seem to be looking for an excuse to get out of helping France. Oh! What a shameful state of things! By God, I don't want to be a Britisher under such conditions!"[18] When it was pointed out that the British cabinet had called an emergency meeting to discuss the invasion of Belgium, Hughes replied: "They are curs enough to do it; I can read between the lines. I believe they will temporize and hum and haw too long-and by God, I don't want to be a Britisher under such conditions-it is too humiliating".[18] Hughes asked if the Union Jack was flying in front of the Defense Department, and upon being told it was, shouted: "Then send up and have it taken down! I will not have it over Canada's military headquarters, when Britain shirks her plain duty-it is disgraceful!"[18] The Union Jack was pulled down, and only put up again the next day, when it was announced that Britain had sent an ultimatum demanding that Germany pull out of Belgium at once, and upon its rejection, Britain had honored the guarantee of Belgium by declaring war on Germany, shortly after midnight on 4 August 1914.[18]

In 1911, the General Staff under Major-General Sir Willoughby Gwatkin had drawn up a plan in the event of a war in Europe for mobilizing the militia that called for Canada to sent an expeditionary force of one infantry division and an independent cavalry brigade together with artillery and support units from the Permanent Force that was to be assembled at Camp Petawawa outside of Ottawa.[11] Much to everyone's surprise, Hughes disregarded the General Staff's plan and refused to mobilize the militia, instead creating a brand new organization called the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) made up of numbered battalions that was separate from the militia.[11] Instead of going to the existing Camp Petawawa, Hughes chose to build a new camp at Valcartier, outside of Quebec City, for the CEF.[11] Hughes's sudden decision to not to call out the militia and create the CEF threw Canadian mobilization into complete chaos as a new bureaucracy had to be created at the same time that thousands of young men flocked for the colors.[11]

Morton wrote that in August–September 1914 "...a sweating, swearing, sublimely happy Hughes pulled some kind of order from the chaos he had created".[23] In the process, Hughes managed to insult everyone from the Governor-General, the Duke of Connaught, to the French-Canadian community.[24] When the president of the Toronto chapter of the Humane Society visited Hughes to express concern about the neglect and mistreatment of horses at Camp Valcartier, Hughes called him a liar and personally picked him up and tossed him out of his office.[16] Likewise, when John Farthing, the Anglican bishop of Montreal, visited Hughes to complain about the shortage of Church of England chaplains at Valcartier to tend to the spiritual needs of Anglican volunteers, Hughes burst into a rage and began to loudly swear at Farthing, making liberal use of a number of four letter words not normally used to address an Anglican bishop, who was predictably shocked.[16] Through Hughes worked hard at ensuring the construction of Camp Valcartier and trying to bring order to the chaos he caused by not calling out the militia, almost everyone who knew him was convinced he was in some way insane.[24] The Duke of Connaught wrote in a report to London that Hughes was "off his base".[24] A Conservative M.P from Toronto, Angus Claude Macdonell, told Borden "The man is insane", and that Canada needed a new defense minister at once.[24] The deputy prime minister, Sir George Foster, wrote in his diary on 22 September 1914: "There is only one feeling about Sam. That he is crazy".[24] The industrialist, Sir Joseph Flavelle, wrote that Hughes was "mentally unbalanced with the low cunning and cleverness often associated with the insane".[24] Borden in his memoirs wrote about Hughes that his behavior was "so eccentric as to justify the conclusion that his mind was unbalanced".[24]

He encouraged recruitment of volunteers when the First World War broke out in 1914, and he constructed a training camp in Valcartier, Quebec. Hughes ordered its construction on August 7, 1914 and demanded it to be finished by the time the entire force was assembled. With the aid of 400 workmen, Hughes saw the completion of Camp Valcartier.[25]

Unfortunately the camp was poorly organized. With approximately 33,000 recruits, training became a chaotic process. There was little time to train the volunteers, so the training system was rushed. Another problem was that the camp's population was constantly growing, which made planning a difficult task. Hughes was infamous for belligerently giving orders to troops and their officers. Hughes publicly criticized officers in front of their men, telling one officer who was speaking too quietly for his liking "Pipe up, you little bugger or get out of the service!".[9] When Hughes addressed one officer as a captain, only to be told by the man that he was a lieutenant, Hughes promoted him on the spot to captain.[16] When it was pointed out that he did not have that power as minister of defence, Hughes shouted "Sir, I know what I'm talking about!" and said if he wanted to promote the officer to a captain, then the officer was a captain.[16] Hughes insisted on riding around the camp surrounded by an honor guard of lancers and shouting out orders for infantry manoeuvres long since removed from the training manuals like "front square!"; when presented with such commands, the soldiers did their best to guess what it was he wanted them to do, through Hughes seemed well satisfied.[26] Volunteer morale was challenged by inadequate tents, shortages of greatcoats and confusion regarding equipment and storage.[27] However, Hughes received praise for the speed of his actions by Prime Minister Robert Borden and members of the cabinet. By October 1914, the troops were mobilized and ready to leave for England.[25]

As the First Contingent boarded their ships in Quebec City on 3 October 1914 to take them to Europe, Hughes sat astride his horse to deliver a speech that caused the men of the First Contingent to boo and jeer him.[28] Borden wrote in his diary that Hughes's speech was "flamboyant and grandiloquent" and that "Everybody laughing at Sam's address".[28]

Hughes left for London at the same time as the First Contingent did, as he heard correct reports that the British War Secretary, Lord Kitchener, was planning on breaking up the CEF when it arrived in Britain to assign its battalions to the British Army.[29] As Hughes took an ocean linear he arrived in Southhampton several days before the CEF did, and upon his landing, he told the British press that if it was not for him that the convoy of 30 ships taking the CEF across the north Atlantic would have been torpedoed by U-boats, through just how Hughes had saved the 30 ships from U-boats was left unexplained.[30] Hughes was determined that the CEF fight together and upon arriving in London, went dressed in his full ceremonial uniform as a major-general in the Canadian militia, to see Kitchener.[31] Hughes clashed with Kitchener and insisted quite vehemently that the CEF not be broken up.[32] In a telegram to Borden, Hughes wrote: "I determined that Canada was not be to treated as a Crown Colony and that, as we paid the bill and furnished the goods, which in nearly every instance were better than the British, I would act".[32] Hughes won his bureaucratic battle with Kitchener and ensured the CEF stay together, mostly by arguing that since the Dominion was paying the entire costs of maintaining the CEF that the Dominion government should have the final say over its deployment.[32] Berton wrote that ensuring the CEF stayed together was Hughes's greatest achievement as without his intervention in October 1914, what ultimately became the Canadian Corps of four divisions would never had existed.[32]

As the CEF took up its training facilities on the Salisbury Plain, Hughes wanted the 1st Canadian Division to be commanded by a Canadian general and only very reluctantly accepted a British officer, Lieutenant-General Sir Edwin Alderson, as the commander of the 1st Division when turned out that there was no qualified Canadian officer.[33] Hughes's insistence on supplying the CEF with Canadian-made equipment, regardless of its quality, made for difficult conditions for the men of the CEF, with many soldiers already complaining about the Ross rifle in training.[33] Alderson replaced the "shield shoves" invented by Hughes's secretary, Ena McAdam, with the standard British Army shovel, much to the relief of the CEF and to Hughes's fury.[33] Hughes constantly sought to undermine Alderson's command, regularly involving himself in divisional matters that were not the normal concern of a defense minister.[33] The first Canadian unit to see action was Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, a regiment privately raised by a wealthy Montreal industrialist, Hamilton Gault, which arrived on the Western Front in December 1914.[33] On 16 February 1915, the CEF arrived in France to head for the front-lines, taking up position at the crucial Ypres salient in Belgium.[33]

On 22 April 1915, at the Ypres salient, the German Army unleashed 160 tons of chlorine gas.[34] From the German lines arouse an ominous yellow cloud which floated across no-man's land to bring death and suffering to the Allied soldiers on the other side, killing 1, 400 French and Algerian soldiers in the trenches, leaving another 2, 000 blinded while the rest broke and fled in terror to escape the deadly yellow cloud of chlorine gas.[34] Despite the dangers of the dreaded chlorine gas which blinded when it did not kill, the 1st Canadian Division stepped up to hold the line on the night of 22–23 April and prevented the Germans from marching through the 4-mile hole in the Allied lines created when the French and Algerians fled.[34] On 23 April, the Germans unleashed the chlorine gas on the Canadian lines, leading to "desperate fighting" as the Canadians used improvised gas-masks of urine-soaked rags while complaining about the Ross rifles, which too often jammed up in combat.[34] The Second Battle of Ypres was the first major battle for the Canadians, costing the 1st Division 6, 035 men killed while the Princess Patrica's battalion lost 678 dead, and gave the CEF a reputation as a "tough force" that was to last for the rest of the war.[34][35] The Canadians had held the line at Ypres in spite of appalling conditions and unlike the French and Algerians, the Canadians did not flee with faced with the sinister yellow cloud of chlorine gas.[34][35]

Hughes was ecstatic that at the news that the Canadians had won their first battle, which in his own mind validated everything he had done as defense minister. At the same time, Hughes attacked Alderson for the losses at Ypres, claiming that a Canadian general would have done a better job and was furious when he learned that Alderson wanted to replace the Ross rifles with Lee-Enfield rifles.[36] In a telegram to Max Aitken, the Canadian millionaire living in London whom Hughes had appointed as his representative in Britain, Hughes wrote: "It is the general opinion that scores of our officers can teach the British officers for many moons to come".[37] In September 1915 the Second Contingent arrived on the Western Front in the form of the 2nd Canadian Division and the Canadian corps was created.[38] Alderson was appointed the corps commander while for first time, Canadians were given divisional command with Arthur Currie of Victoria taking command of the 1st Division and Richard Turner of Quebec City taking command of the 2nd Division.[35] Hughes himself had wanted to take command of the Canadian Corps, but Borden had prevented this.[35]

Hughes was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, on August 24, 1915. In 1916 he was made an honorary Lieutenant-General in the British Army.[39] A Regimental and King’s Colours display and plaque at Knox Presbyterian Church (Ottawa) is dedicated to the memory of those who served in the 207th (Ottawa-Carleton) Battalion, CEF during the First World War. The Regimental Colours were donated by the American Bank Note Company and presented by Hughes to the battalion on Parliament Hill on November 18, 1916.[40] In spite of mounting criticism from 1915 onward at the way in which Hughes ran the Defense Department in wartime, Borden kept Hughes on.[22] Borden owned Hughes a major political debt going to his days as the embattled Leader of the Official Opposition, when the shadow defense minister had been loyal to him at a time when many Conservative MPs wanted a new leader after Borden lost two general elections in a row in 1904 and 1908.[22] Furthermore, events seemed to prove that many of Hughes's opinions were right, as Borden visited the Western Front in the summer of 1915 and became convinced that much of what Hughes had to say about the inefficiency of the British Army was correct.[22] Hughes's methods were unorthodox and chaotic, but Hughes argued he was merely cutting through the red-tape to help "the boys" in the field.[22] And finally, Borden in his dealings with British officials often found them patronising and condescending, which led him to side with his nationalist defense minister who argued that Canadians were the equals of the "mother country" in imperial affairs, and should not be talked down to.[22]

Hughes was an Orangeman prone to anti-Catholic sentiments, who was not well liked among French Canadians. Hughes increased tensions by sending Anglocentrics to recruit French Canadians, and by forcing French volunteers to speak English in training. Hughes reluctantly accepted Japanese-Canadians and Chinese-Canadians for the CEF and assigned black Canadians to construction units.[41] However, some black Canadians did manage to enlist as infantrymen as Chartrand noted that in a painting by Eric Kennington of the 16th Canadian Scottish battalion marching through the ruins of some French village, one of the soldiers wearing kilts in the painting is a black man.[42] In marked contrast to his attitudes towards black Canadian and Asian Canadian volunteers, Hughes encouraged the enlistment of First Nations volunteers into the CEF as it was believed that Indians would make for ferocious soldiers.[41]

Over the course of the war, the policies carried out by the Ministry of Defense and Militia were much marked by much inefficiency and waste, largely caused by Hughes as Morton wrote: "Hughes's perennial contempt for military professionals, shared by his overseas agent, Max Aitken, became an excuse for chaos and influence-peddling in militia administration".[22] As scandals continued from the exposure of wasteful purchasing in 1915 to the "munitions scandal" of 1916 which exposed Hughes's flunky J. Wesley Allison as corrupt, Borden took away various functions from Defense Ministry to be handled by an independent board or commission headed by men who were not cronies of Hughes.[22] Hughes's was widely resented and disliked by the men of the CEF and when Hughes visited Camp Borden in July 1916, "his boys" loudly booed him, blaming the minister for the shortages of water at Camp Borden.[22]

Hughes's policy of raising new battalions instead of sending the reinforcements to the existing battalions led to much administrative waste and ultimately led to most of the new battalions being broken up to provide menpower for the older battalions.[43] To manage the Canadian Expeditionary Force in London, Hughes created a confusing system of overlapping authorities run by three senior officers, in order to make himself the ultimate arbiter of every issue.[43] The most important of the officers in England was Major General John Wallace Carson, a mining magnate from Montreal and a friend of Hughes, who proved himself a skillful intriguer.[43] While the officers in London feuded for Hughes's favor, what Morton called a "...burgeoning, wasteful, array of camps, offices, depots, hospitals and commands spread out across England".[43] Twice, Borden sent Hughes to England to impose order and efficiency, and twice the prime minister was gravely disappointed.[43] In September 1916, Hughes acting on his own and without informing Borden, announced in London the formation of the "Acting Overseas Sub-Militia Council" to be chaired by Carson with Hughes's son-in-law to serve as the chief secretary.[43]

His historical reputation was sullied further by poor decisions on procurements for the force. Insisting on the utilization of Canadian manufactured equipment, Hughes presided over the deployment of equipment that was often inappropriate for the Western Front, or of dubious quality. Previous to 1917, this had negatively affected the operational performance of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.[44] The Ross rifle, MacAdam Shield Shovel, boots and webbing (developed for use in the South African War), and the Colt machine gun were all Canadian items which were eventually replaced or abandoned due to quality or severe functionality issues. The management of spending for supplies was eventually taken away from Hughes and assigned to the newly formed War Purchasing Commission in 1915.[45] It was not until Hughes' resignation in November 1916 that the Ross Rifle, which often jammed in trench warfare conditions, was fully abandoned in favour of the British standard Lee–Enfield rifle.

Canadian staff officers possessed an extremely limited level of experience and competence at the start of the war, having been discouraged from passing through the British Staff College for many years prior.[46] Compounding the issue was Sir Samuel Hughes' regular attempts to promote and appoint officers based upon patronage and Canadian nativism instead of ability, an act which not only created tension and jealousy between units but ultimately negatively affected the operating performance of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) as well.[46] Lieutenant General Byng, commander of the CEF from May 1916, eventually became so incensed with the continuous interference on the part of Hughes that he threatened to resign. Byng, an aristocrat and a career British Army officer who was modest in his tastes and known for his care for his men, was very popular with the rank and file of the Canadian Corps, who called themselves "the Byng boys".[47] This in turn sparked Hughes's jealously. On 17 August 1916, Byng and Hughes had dinner where Hughes announced his typical bombastic way that he never made a mistake and would hold the power of promotion within the Canadian Corps; Byng in reply stated that as a corps commander he had the power of promotion, that he would inform Hughes before any making promotions as a courtesy, and would resign if Hughes continued his interference with his command in the same way he had with Alderson.[48] Byng wanted to give command of the 2nd Division to Henry Burstall, who had greatly distinguished himself, over the objections of Hughes, who wanted to give command of the 2nd Division to his son Garnet, whom Byng regarded as a mediocrity unfit to command anything.[49] Byng wrote to Borden to say that he would not tolerate political interference in his corps, and he would resign if the younger Hughes was given the command of the 2nd Division rather than Burstall, who did indeed receive the appointment.[49]

Criticism from Field Marshal Douglas Haig, King George V and from within his own party gradually forced Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden to tighten control over Hughes.[50] However, it was not until Hughes' political isolation, with the creation of the Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada, overseen by Albert Edward Kemp, and subsequent forced resignation in November 1916, that the CEF was able to concentrate on the task of the spring offensive without persistent staffing interference.[51] The creation of the Ministry of Overseas Military Forces to run the CEF was a much reduction in Hughes's power, causing him to rage and threaten Borden.[43] After Hughes sent Borden an extremely insulting letter on 1 November 1916, the prime minister vacillated for the next 9 days before making his decision.[48] Borden's patience with Hughes finally and he dismissed him from the cabinet on 9 November 1916.[43]

Hughes later claimed in Who's Who to have served "in France, 1914-15"[3] despite not being released from his ministry and not having been given any command in the field. His presence at the Western Front was limited to his visits to troops.

Death

Sam Hughes died of pernicious anaemia, aged sixty-eight, in August 1921 and was survived by his son, Garnet Hughes, who served in the First World War, and his grandson, Samuel Hughes, who was a field historian in the Second World War and later a judge. He and his wife are buried in Lindsay, Ontario.

Plaque

A memorial plaque dedicated to the memory of Sam Hughes was erected in front of the Armouries building in Lindsay, Ontario. It reads:

Soldier, journalist, imperialist and Member of Parliament for Lindsay, Ontario from 1892 to 1921, Sam Hughes helped to create a distinctively Canadian Army. As Minister of Militia and Defence (1911–1916) he raised the Canadian Expeditionary Force which fought in World War I, and was knighted for his services. Disagreements with his colleagues and subordinates forced his retirement from the Cabinet in 1916."[52][53]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sam Hughes. |

- ↑ Halsey, Francis Whiting (1920). History of the World War. Ten. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. p. 147.

- ↑ Capon, Alan (1969). His Faults Lie Gently: The Incredible Sam Hughes. Lindsay, Ontario: F. W. Hall. p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Who Was Who, 1916-1928. A and C Black. 1947. p. 528. Note the order in which they are quoted is not chronological.

- 1 2 Morton 1999, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morton 1999, p. 114.

- ↑ Morton 1999, pp. 113-114.

- 1 2 3 Morton 1999, p. 115.

- ↑ Morton 1999, p. 117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berton 1986, p. 41.

- 1 2 Morton 1999, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chartrand 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ "Hughes, Sam". Trent University Archives. trentu.ca. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ↑ "Canadian Personaities: Lieutenant-Colonel Sam Hughes (1853-1921)". Canada & The South African War, 1899-1902. Canadian War Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chartrand 2007, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Morton 1999, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Berton 1986, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Morton 1999, p. 127-128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berton 1986, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Morton 1999, p. 128.

- ↑ Morton 1999, p. 128-129.

- ↑ Morton 1999, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Morton 1999, p. 146.

- ↑ Morton 1999, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Berton 1986, p. 39.

- 1 2 "ebrary: Server Message". site.ebrary.com. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ↑ Berton 1986, p. 42.

- ↑ Berton 1986, p. 38-39.

- 1 2 Berton 1986, p. 42-43.

- ↑ Berton 1986, p. 43.

- ↑ Berton 1986, p. 43-44.

- ↑ Berton 1986, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 Berton 1986, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morton 1999, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chartrand 2007, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 Morton 1999, p. 141.

- ↑ Morton 1999, p. 141-142.

- ↑ Morton 1999, p. 142.

- ↑ Chartrand 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Kelly's Handbook to the Titled, Landed and Official Classes, 1920. Kelly's. p. 867.

- ↑ "207th (Ottawa-Carleton) Battalion, CEF memorial". National Defence Canada. 2008-04-16. Archived from the original on 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- 1 2 Morton 1999, p. 136.

- ↑ Chartrand 2007, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Morton 1999, p. 147.

- ↑ Haycock 1986, pp. 272.

- ↑ McInnis 2007, pp. 408–409.

- 1 2 Dickson 2007, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Berton 1986, p. 93-94.

- 1 2 Berton 1986, p. 65.

- 1 2 Berton 1986, p. 100.

- ↑ Dickson 2007, pp. 43.

- ↑ Haycock 1986, pp. 306–308.

- ↑ "Sir Sam Hughes, 1853-1921". Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ↑ Clifford, David & Kellie. "Sir Sam Hughes, 1853-1921". Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

See also

- Canadian Aviation Corps

- Nickle Resolution - a policy in place since 1917 that occurred after Hughes' knighthood

References

- Berton, Pierre (2010). Vimy. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited.

- Chartrand, René (2007). The Canadian Corps in World War I. London: Opsrey.

- Dickson, Paul (2007). "The End of the Beginning: The Canadian Corps in 1917". In Hayes, Geoffrey; Iarocci, Andrew; Bechthold, Mike. Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 31–49. ISBN 0-88920-508-6.

- Haycock, Ronald (1986). Sam Hughes: The Public Career of a Controversial Canadian, 1885–1916. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-177-3.

- Morton, Desmond (1999). A Military History of Canada. McClelland & Stewart.

- McInnis, Edgar (2007). Canada - a Political and Social History. Toronto: McInnis Press. ISBN 1-4067-5680-6.

External links

- "Sam Hughes". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

- Sam Hughes – Parliament of Canada biography

| 10th Ministry – Second cabinet of Robert Borden | ||

| Cabinet post (1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predecessor | Office | Successor |

| Frederick William Borden | Minister of Militia and Defence 1911–1916 |

Albert Edward Kemp |

| Parliament of Canada | ||

| Preceded by John Augustus Barron |

Member of Parliament from Victoria North 1892–1904 |

Succeeded by district abolished in 1903 |

| Preceded by None |

Member of Parliament from Victoria 1904–1921 |

Succeeded by John Jabez Thurston |