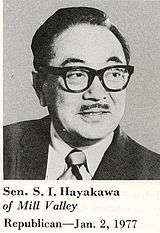

S. I. Hayakawa

| S. I. Hayakawa | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from California | |

|

In office January 2, 1977 – January 3, 1983 | |

| Preceded by | John V. Tunney |

| Succeeded by | Pete Wilson |

| 9th President of San Francisco State University | |

|

In office November 26, 1968 – July 10, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Smith |

| Succeeded by | Paul Romberg |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa July 18, 1906 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

| Died |

February 27, 1992 (aged 85) Greenbrae, California, U.S. |

| Political party |

Democratic (before 1973) Republican (1973–1992) |

| Spouse(s) | Margedant Peters |

| Children | 3 |

| Education |

University of Manitoba (BA) McGill University (MA) University of Wisconsin, Madison (PhD) |

| Academic background | |

| Thesis | Oliver Wendell Holmes: Physician, poet, essayist (1935) |

| Doctoral advisor | . |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | English |

| Sub-discipline | Linguistics, semantics |

| Institutions | |

| Notable works | Language in Thought and Action |

Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa (July 18, 1906 – February 27, 1992) was a Canadian-born American academic and politician of Japanese ancestry. A professor of English, he served as president of San Francisco State University,[1] and then as U.S. Senator from California from 1977 to 1983.[2]

Early life and education

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Hayakawa was educated in the public schools of Calgary, Alberta, and Winnipeg, Manitoba, and received an undergraduate degree from the University of Manitoba in 1927 and graduate degrees in English from McGill University in 1928 and the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1935.[3]

Academic career

Professionally, Hayakawa was a linguist, psychologist, semanticist, teacher, and writer. He served as an instructor at the University of Wisconsin from 1936 to 1939 and at the Armour Institute of Technology (now Illinois Institute of Technology) from 1939 to 1948.

His first book on semantics, Language in Thought and Action, was published in 1949 as an expansion of the earlier work, Language in Action, written since 1938 and published in 1941 to be a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. It is currently in its fifth edition and has greatly helped to popularize Alfred Korzybski's general semantics and semantics in general, while semantics or theory of meaning was overwhelmed by mysticism, propagandism and even scientism. In the preface, Hayakawa cautioned:

The original version of this book, Language in Action, published in 1941, was in many respects a response to the dangers of propaganda, especially as exemplified in Adolf Hitler's success in persuading millions to share his maniacal and destructive views. It was the writer's conviction then, as it remains now, that everyone needs to have a habitually critical attitude towards language—his own as well as that of others—both for the sake of his personal well being and for his adequate functioning as a citizen. Hitler is gone, but if the majority of our fellow citizens are more susceptible to the slogans of fear and race hatred than to those of peaceful accommodation and mutual respect among human beings, our political liberties remain at the mercy of any eloquent and unscrupulous demagogue.

In addition to such motivation, he acknowledged his debt as follows:

My deepest debt in this book is to the General Semantics ('non-Aristotelian system') of Alfred Korzybski. I have also drawn heavily upon the works of other contributors to semantic thought: especially C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards, Thorstein Veblen, Edward Sapir, Leonard Bloomfield, Karl R. Popper, Thurman Arnold, Jerome Frank, Jean Piaget, Charles Morris, Wendell Johnson, Irving J. Lee, Ernst Cassirer, Anatol Rapoport, Stuart Chase. I am also deeply indebted to the writings of numerous psychologists and psychiatrists with one or another of the dynamic points of view inspired by Sigmund Freud: Karl Menninger, Trigant Burrow, Carl Rogers, Kurt Lewin, N. R. F. Maier, Jurgen Ruesch, Gregory Bateson, Rudolf Dreikurs, Milton Rokeach. I have also found extremely helpful the writings of cultural anthropologists, especially those of Benjamin Lee Whorf, Ruth Benedict, Clyde Kluckhohn, Leslie A. White, Margaret Mead, Weston La Barre.

He was a lecturer at the University of Chicago from 1950 to 1955. During this time he presented a talk at the 1954 Conference of Activity Vector Analysts[4] at Lake George, New York, in which he discussed a theory of personality from the semantic point of view. This was later published as The Semantic Barrier. This was a definitive lecture as it discussed the Darwinism of the "survival of self" as contrasted with the "survival of self-concept". His ideas on general semantics influenced A. E. van Vogt's Null-A novels, The World of Null-A and The Pawns of Null-A. Van Vogt in The World of Null-A (i.e., non-Aristotelian) makes Hayakawa a character, introducing him as: "Professor Hayakawa is today's Mr. Null-A himself, the elected head of the International Society for General Semantics."[5]

Hayakawa was an English professor at San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University) from 1955 to 1968. In the early 1960s, he helped organize the Anti Digit Dialing League, a San Francisco group that opposed the introduction of all-digit telephone exchange names. Among the students he trained were commune leader Stephen Gaskin and author Gerald Haslam. He was named acting president of San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University) on November 26, 1968, when Ronald Reagan was governor of California and Joseph Alioto was mayor of San Francisco.[6] On July 9, 1969, the California State Colleges Board of Trustees appointed Hayakawa the ninth president of San Francisco State.[7] Hayakawa retired on July 10, 1973.[1][8]

Hayakawa wrote a column for the Register and Tribune Syndicate from 1970 to 1976. In 1973, Hayakawa changed his political affiliation from the Democratic Party to Republican Party and became president emeritus at what became San Francisco State University.[9]

Student strike at San Francisco State College

In 1968–69, there was a bitter student and Black Panthers strike at San Francisco State University in order to establish an ethnic studies program. It was a major news event at the time and chapter in the radical history of the United States and the Bay Area. The strike was led by the Third World Liberation Front supported by Students for a Democratic Society, the Black Panthers and the countercultural community.

It proposed fifteen "non-negotiable demands", including a Black Studies department chaired by sociologist Nathan Hare independent of the university administration and open admission to all black students to "put an end to racism", and the unconditional, immediate end to the War in Vietnam and the university's involvement. It was threatened that if these demands were not immediately and completely satisfied the entire campus was to be forcibly shut down.[10] Hayakawa became popular with conservative voters in this period after he pulled the wires out from the loud speakers on a protesters' van at an outdoor rally.[1][11][12][13] Hayakawa relented on December 6, 1968, and created the first-in-the-nation College of Ethnic Studies[14]

Political career

Hayakawa won an unexpected victory in the 1976 Republican senate primary over three better-known career politicians including HEW Secretary Robert Finch, long-time Congressman Alphonso Bell, and California Lt. Governor John L. Harmer. Much like Jimmy Carter, Hayakawa touted himself as a political outsider.

On the Democratic side, incumbent Senator John Tunney faced a surprisingly strong challenge from another political outsider, Tom Hayden. Hayden's extremely liberal candidacy forced Tunney to run more to the left in the primary, which hurt him in the general election.

Nevertheless, Tunney was favored to easily win re-election. Comfortably ahead in the polls, Tunney did not aggressively campaign until the final weeks before the election. But Hayakawa's position as a political outsider was popular in the wake of the Watergate Scandal. In addition, Tunney had a high absenteeism rate while serving in the Senate and missed numerous votes. Hayakawa exploited this with a TV ad that showed an empty chair in the US Senate chamber. Hayakawa gradually closed the gap with Tunney, and ultimately defeated him by just over three percentage points.

During his 1976 Senate campaign, he spoke about the proposal to transfer possession of the Panama Canal and Canal Zone from the United States to Panama. Hayakawa said, "We should keep the Panama Canal. After all, we stole it fair and square."[15] However, in 1978 he helped win Senate approval of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties, which transferred control of the zone and canal to Panama.[16] He also supported a bill that led to the creation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which examined the causes and effects of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.[17] During his time in the U.S. Senate, Hayakawa was one of three Japanese Americans in the chamber, the other two being Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga, both of Hawaii.

He planned to run for reelection in 1982 but trailed other Republican candidates badly in early polls and was short on money. He dropped out of the race early in the year and was ultimately succeeded by Republican San Diego mayor Pete Wilson.

Hayakawa founded the political lobbying organization U.S. English, which is dedicated to making the English language the official language of the United States.[18]

[19] Hayakawa, who lived in Chicago as a Canadian citizen during World War II and was thus not subject to confinement,[2] argued that the internment of Japanese Americans "eventually worked to their advantage" and that Japanese Americans should not be paid for "fulfilling their obligations" to submit to Executive Order 9066.[17][20]

Personal life

Hayakawa was a resident of Mill Valley, California, until his death in nearby Greenbrae, in 1992. He was also a member of the Bohemian Club. He had an abiding interest in traditional jazz and wrote extensively on that subject, including several erudite sets of album liner notes. Sometimes in his lectures on semantics, he was joined by the respected traditional jazz pianist Don Ewell, whom Hayakawa employed to demonstrate various points in which he analyzed semantic and musical principles. Hayakawa was often favorite fodder for the news media reporters, every time he was found napping through important legislative voting.[2]

He was the nephew-in-law of Joseph Stalin, in that his wife Margedant's brother William Wesley Peters was married to Stalin's daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva.[21]

See also

Bibliography

- Hayakawa, S. I. Choose the Right Word: A Modern Guide to Synonyms and Related Words. 1968. Reprint. New York: Perennial Library, 1987. Originally published as Funk & Wagnalls Modern Guide to Synonyms and Related Words.

- Hayakawa, S. I. "Education Revisited". In The World Today, edited by Phineas J. Sparer. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1975.

- Hayakawa, S. I. Language in Thought and Action. 1939. Enlarged ed. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978. Originally published as Language in Action.

- Hayakawa, S. I. Symbol, Status, and Personality. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1963.

- Hayakawa, S. I. Through the Communication Barrier: On Speaking, Listening, and Understanding. Edited by Arthur Chandler. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

- Hayakawa, S. I., ed. Language, Meaning, and Maturity. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954.

- Hayakawa, S. I., ed. Our Language and Our World. 1959. Reprint. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

- Hayakawa, S. I., ed. The Use and Misuse of Language. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, 1964.

- Hayakawa, S. I., and William Dresser, eds. Dimensions of Meaning. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1970. Includes Hayakawa's essays "General Semantics and the Cold War Mentality" and "Semantics and Sexuality".

- Paris, Richard, and Janet Brown, eds. Quotations from Chairman S. I. Hayakawa. San Francisco: n.p., 1969.

References

- 1 2 3 "Hayakawa will retire". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (Los Angeles Times). October 13, 1972. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 "S.I. Hayakawa, 85, dies; challenged '60s radicals". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). (Los Angeles Times). February 28, 1992. p. 7A.

- ↑ Hayakawa, Samuel I. (1935). Oliver Wendell Holmes: Physician, poet, essayist (Ph.D.). University of Wisconsin–Madison. OCLC 51566055 – via ProQuest. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "WebAVA". Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ↑ Alfred Elton Van Vogt (1977). The World of Null-A. New York: Berkley Books. p. 11. ISBN 9780425054543.

- ↑ "Case 3: Prelude / Demands". On Strike! Shut it Down! (Exhibit 1999). Leonard Library, San Francisco State University. Archived from the original on August 31, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ Reagan: A Life In Letters. Simon and Schuster. 2004. p. 187. ISBN 0743219678.

- ↑ Bittlingmayer, George (July 17, 1973). "San Francisco State Faculty Protests Selection of Hayakawa's Successor". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Guide to the Samuel I. Hayakawa Papers". Online Archive of California. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ Hayward, Steven. The Age of Reagan, Volume I. Crown Forum. p. 446.

- ↑ James M. Fallows (January 15, 1969). "Song of Hayakawa". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ↑

Yaga.com - ↑ "The San Francisco State College Strike Collection, Chronology of events". Leonard Library. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ↑ Hayakawa & angry demonstrations, Part I. KQED News. San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive. December 6, 1968. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ↑ "We Should Keep The Panama Canal. After All, We Stole It Fair And Square. – S.I". Anvari.org. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ staff (February 28, 1992). "Ex-Sen. Hayakawa Dies; Unpredictable Iconoclast ..." Los Angeles Times.

- 1 2 Robinson, Greg. S.I. Hayakawa. Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Language politics and policy in the United States: Implications for the immigration debate*, Working Paper 141" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2006.

- ↑ Maki, Mitchell Takeshi; Kitano, Harry H. L.; Berthold, Sarah Megan (1999). Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress. University of Illinois. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0-252-02458-3.

- ↑ Testimony of S.I. Hayakawa on Senate Bill 2116. Presented to Subcommittee on Appropriations, August 16, 1984. (Transcript available in Densho Digital Archive, courtesy of Cherry Kinoshita.)

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1992/02/28/outspoken-us-senator-si-hayakawa-dies-at-85/761fdf45-6557-4b88-99fc-1a66d5628e43/

- United States Congress. "S. I. Hayakawa (id: H000384)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Fox, R. F. (1991). A conversation with the Hayakawas. The English Journal, Vol. 80, No. 2 (Feb., 1991), pp. 36–40.

- Haslam, Gerald, and Janice E. Haslam. In Thought and Action: The Enigmatic Life of S. I. Hayakawa (U. of Nebraska Press; 2011) 427 pages; scholarly biography

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: S. I. Hayakawa |

- Samuel I. Hayakawa papers at the Hoover Institution Archives

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Australian General Semantics Society

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Murphy |

Republican nominee for U.S. Senator from California (Class 1) 1976 |

Succeeded by Pete Wilson |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by John V. Tunney |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from California 1977–1983 Served alongside: Alan Cranston |

Succeeded by Pete Wilson |

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Robert Smith |

President of San Francisco State University 1968–1973 |

Succeeded by Paul Romberg |