Exorcism in Islam

Exorcism in Islam is called ruqya shar'iyah (Arabic: رقية شرعية IPA: [ruqya sharʕiya]), and is thought to repair damage believed caused by jinn possession[1][2][3] witchcraft (shir) or the evil eye. Exorcisms today are part of a wider body of contemporary Islamic alternative medicine[4] called al-Tibb al-Nabawi (Medicine of the Prophet).

Islamic religious context

Belief in Jinns, and other supernatural beings, is widespread in the Islamic world. Jinn is an Arabic collective noun deriving from the Semitic root jnn (Arabic: جَنّ / جُنّ, jann), whose primary meaning is "to hide".[5][6]:68[7]:193:341 Some authors interpret the word to mean, literally, "beings that are concealed from the senses". Such creatures are believed to inhabit desolate, dingy, dark places where they are feared. Jinn exist invisibly amongst humans, only detectable with the sixth sense. The jinn are subtile creatures created from smokeless fire (fire and air) thought to be able to possess animate and inanimate objects. Unlike demons, they are not necessarily evil, but own a capacity of free-will.[8]

Reasons for possession

Possession is not caused by Satan,[9] who is said to be just a tempter, whispering evil suggestions into humans heart, but, even though not mentioned in canonical scriptures, according to folklore by jinn, who can enter a human body physically or haunting them mentally. A possession by a jinn can happen for various reasons. Ibn Taymiyyah explained a Jinn could sometimes haunt an individual, because the person could (even unintentionally) harm the jinn; urinating or throwing hot water on it, or even killing a related jinn without even realizing it.[10] In this case the jinn will try to take revenge on the person. Another cause for jinn possession is when a jinn falls in love with a human and thereupon the jinn possesses the human.[11] Some women have told of their experiences with jinn possession; where the jinn tried to have sexual interaction from inside their bodies.[12] Thirdly, it occurs when a jinn is evil and simply wants to harm a human for no specific reason, it will possess that person, if it gets the opportunity, while the human is in a very emotional state or unconsciousness.[11] Jinn may also haunt someone in service of a sorcerer.[8]

Signs of possession

In Islamic belief, there are different signs of possession for example:[11]

- Procrastination in doing good acts or praying

- Constant laziness

- Recurring aggression

- Loss of senses while awake

- Constant headaches

- Recurring nightmares

- Laughing while asleep

- Sleepwalking

In case of a "complete control" by the Jinn, the possessed surrender to the Jinn and the persons consciousness is subverted by it. Such a jinn is indeed absolutely evil and thereupon the acts of the person are going to be evil as well. The person will obey the commands of the jinn at anytime. In a "constant possession" the person will not act without a command by the jinn.

According to reports of individuals who have claimed to be possessed, they've asserted that during the jinn possession their spiritual abilities, like the sixth sense, had increased.[12] Possession can also cause physical damage, such as inexplicable bruising or marks appearing spontaneously.[13]

Procedure

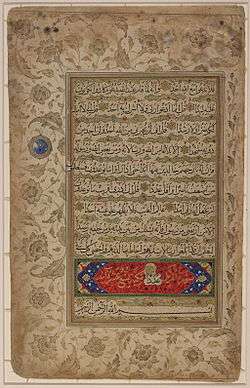

Recited formulas, referred to as Ruqyah are used to expel the Jinn from the body. Majority of Ruqyah are either charms or spells that are uttered or written. Nushrah refers to charms or amulets that are used.

In a typical Islamic exorcism the treated person lies down while a white-gloved therapist places a hand on their head while reciting verses from the Quran.[1][14]

Specific verses from the Quran are recited, which glorify God (e.g. The Throne Verse (Arabic: آية الكرسي Ayatul Kursi) and invoke his help. In some cases the adhan (call for daily prayers) is also read, believed to have the effect of repelling non-angelic unseen beings or the jinn.

The Islamic prophet Muhammad taught his followers to read the last three suras from the Quran, Surat al-Ikhlas (The Fidelity), Surat al-Falaq (The Dawn) and Surat an-Nas (Mankind).

A common healing practice in classical Islam used music to cure mental illnesses, related to jinn-possession.[15]

Islamic Exorcists

Those who are permitted to perform exorcisms typically have other careers but possess the ability to exorcise.

Exorcism and Islamic Law

Prohibited techniques[16] often utilize shirk, which is found in practices that prepare amulets or talismans. This is prohibited because shirk is the sin of practicing idolatry or polytheism i.e. the deification or worship of anyone or anything besides the singular God. Many times Qur'anic verses are added throughout the recitation when using these objects in order to 'mask' their shirk. However, God believes he has provided sufficient cures in executing an exorcism, therefore exorcists should not have to rely on methods involving shirk.[16] Additionally, individuals seeking exorcism should avoid magicians or soothsayers because these magical practices go against Islamic Law.

Hadith of the 70,000 who do not ask for ruqya and will not be brought to account

A hadith recorded in Sahih al-Bukhari, 8:76:479 states: "Seventy thousand people of my followers will enter Paradise without accounts, and they are those who do not practice Ar-Ruqya and do not see an evil omen in things, and put their trust in their Lord." Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, a scholar, commented on this hadith, stating: “That is because these people will enter Paradise without being called to account because of the perfection of their Tawheed, therefore he described them as people who did not ask others to perform ruqyah for them. Hence he said "and they put their trust in their Lord." Because of their complete trust in their Lord, their contentment with Him, their faith in Him, their being pleased with Him and their seeking their needs from Him, they do not ask people for anything, be it ruqyah or anything else, and they are not influenced by omens and superstitions that could prevent them from doing what they want to do, because superstition detracts from and weakens Tawheed".[17][2]

See also

References

- 1 2 Hallowell, Billy (26 September 2011). "Some Asian Muslims Giving Up Western Meds for Islamic Exorcisms & Treatments". TheBlaze.

- 1 2 Malik, Mohammad Manzoor (2013). "Islamic Perseptions of Medication with Special Reference to Ordinary and Extraordinary Means of Medical Treatment". citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. p. 23. Archived from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

The second type of traditions speaks about the tawakkul (reliance upon God). For example, "Whoever seeks treatment by cauterization, or with ruqyah (incantation) then he has absolved himself of tawakkul (reliance upon Allah)."30 The Prophet also said that seventy thousand men of his Ummah (Muslims), who neither practice charm, not take omens, nor do they cauterize, but they repose their trust in their lord, would enter paradise without rendering account.31 However, as mentioned earlier, medication is allowed and encouraged and so is ruqyah (incantation) allowed and proven as stated in the prophetic traditions. To suffice, "The Prophet used to treat some of his wives by passing his right hand over the place of ailment and used to say, "O Allah, the lord of the people! Remove the trouble and heal the patient, for you are the healer. No healing is of any avail but yours; healing that will leave behind no ailment".32 Furthermore, medication is part of the destiny one will come across as Abu Khuzamah narrated: "I said, O Messenger of Allah, the ruqyah (divine remedies - Islamic supplication formula) that we use, the medicine we take and the prevention we seek, does all this change Allah‟s appointed destiny? He said, They are in fact a part of Allah‟s appointed destiny". 33

- ↑ "Imam filmed carrying out exorcism on woman to help her find a husband". Metro. 2018-02-02. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ↑ Hall, Helen (2018-04-17). "Exorcism – how does it work and why is it on the rise?". The Conversation. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

Beliefs and rituals which could appropriately be labelled exorcism are found in almost all cultures and faith traditions, but in the West are encountered most frequently within Christian or Islamic settings.

- ↑ Quran 51:56–56

- ↑ al-Ṭabarī, Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb. Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib. I.

- ↑ Rāzī, Abū al-Futūḥ. Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān.

- 1 2 Joseph P. Laycock Spirit Possession around the World: Possession, Communion, and Demon Expulsion across Cultures ABC-CLIO 2015 ISBN 978-1-610-69590-9 page 166

- ↑ N. Ahmadi Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual Springer 1998 ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5 page 79

- ↑ ʻUmar Sulaymān Ashqar The World of the Jinn and Devils Islamic Books 1998 page 204

- 1 2 3 Moiz Ansari Islam And the Paranormal: What Does Islam Says About the Supernatural in the Light of Qur'an, Sunnah And Hadith iUniverse 2006 ISBN 978-0-595-37885-2 page 55

- 1 2 Kelly Bulkeley, Kate Adams, Patricia M. Davis Dreaming in Christianity and Islam: Culture, Conflict, and CreativityRutgers University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0-813-54610-0 page 148

- ↑ G. Hussein Rassool Islamic Counselling: An Introduction to Theory and Practice Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-317-44125-0 page 58

- ↑ Staff (14 May 2012). "Belgium court charges six people in deadly exorcism of Muslim woman". Al Arabiya.

- ↑ Josef W. Meri Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia Routledge 2005 ISBN 978-1-135-45596-5 page 496

- 1 2 "Chapter 4: Other Beliefs and Practices". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2012-08-09. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

Islamic tradition also holds that Muslims should rely on God alone to keep them safe from sorcery and malicious spirits rather than resorting to talismans, which are charms or amulets bearing symbols or precious stones believed to have magical powers, or other means of protection.

- ↑ al-Jawziyya, Ibn Qayyim. Zad al-Ma'ad [Provisions of the Hereafter]. pp. 1/475.