Running injuries

| Running injuries | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources |

Running is a form of exercise and described as the one of the world's most accessible sport. However, its high-impact nature can lead to injury. Approximately 50% of runners are affected by some form of running injuries or running-related injuries (RRI) annually, and some estimates suggest an even higher frequency. The frequency of various RRI depend on the type of running, as runners vary significantly in factors such as speed and mileage. RRI can be both acute and chronic. Many of the common injuries that plague runners are chronic, developing over a longer period of time, as opposed to injury caused by sudden trauma, such as strains. These are often the result of overuse. Common overuse injuries include stress fractures, Achilles tendinitis, Iliotibial band syndrome, Patellofemoral pain (runners knee), and plantar fasciitis.

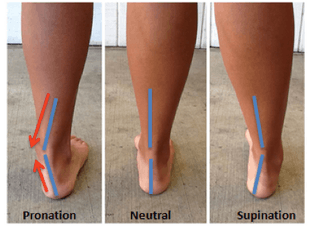

Proper running form is important in injury prevention. A major aspect of running form is foot strike pattern. The way in which the foot makes contact with the ground determines how the force of the impact is distributed throughout the body. Different types of modern running shoes are created to manipulate foot strike pattern in an effort to reduce the risk of injury. In recent years, barefoot running has increased in popularity in many western countries, because of claims that it reduces the risk of injury. However, this has not been proven and is still debated.[1]

Overuse injuries

Causes and prevention

In general, overuse injuries are the result of repetitive impact between the foot and the ground. With improper running form, the force of the impact can be distributed abnormally throughout the feet and legs. Running form tends to worsen with fatigue. When moving at a constant pace, a symmetrical gait is considered to be normal. Asymmetry is considered to be a risk factor for injury. One study attempted to quantify the change in running form between a rested and fatigued state by measuring asymmetrical running gait in the lower limbs. The results showed that "knee internal rotation and knee stiffness became more asymmetrical with fatigue, increasing by 14% and 5.3%, respectively".[2] These findings suggest that focusing on proper running form, particularly when fatigued, could reduce the risk of running related injuries. Running in worn out shoes may also increase the risk of injury and altering the footwear might be helpful. These injuries can also arise due to a sudden increase in the intensity or amount of exercise.

Achilles tendinitis

Achilles tendinitis is the inflammation of the Achilles tendon, resulting in pain along the back of the leg near the heel. There are two types of Achilles tendinitis, insertional and noninsertional. Noninsertional Achilles tendinitis is the type that more commonly affects runners. In this case, inflammation is occurring in the middle portion of the tendon, whereas insertional Achilles tendinitis is inflammation located where the tendon connects (inserts) to the heel bone. Having tight calf muscles may also increase the risk of Achilles tendinitis. Stretching the calves before starting heavy exercise may help relieve tightness in the muscles.[3]

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome is associated with pain in the knee and around the patella. It is sometimes referred to as runner's knee, but this term is used for other overuse injuries that involve knee pain as well. It can be caused by a single incident, but is often the result of overuse or a sudden icrease in physical activity.

Iliotibial band syndrome

Iliotibial band syndrome is defined as inflammation of the iliotibial band on the outside of the knee. This inflammation occurs a result of the iliotibial band and the outside of the knee join rubbing together. The resulting pain typically is initially mild and worsens if running continues. Recurrence is a common issue with iliotibial band syndrome, as pain goes away with a period of rest, but symptoms can easily come back as the runner returns to training. During recovery, the muscles on the outside of the hip can be stretched to reduce tightness in the band.

Footwear

Traditional running shoes

So called 'traditional' running shoes are designed to give more support and cushion the landing to reduce the effects of impact. They allow for more comfortable running on hard surfaces such as asphalt and also protect the foot when stepping on rocks or other potentially sharp objects. However, the cushioning provided in traditional running shoes is thought to encourage a foot strike pattern, where the heel lands first. Heel striking generates a relatively large amount of impact force that can put different parts of the lower extremities under excessive stress.

Barefoot running

Barefoot running has been promoted as one method of reducing the risk of running related injuries. Barefoot running is thought to improve running form by encouraging forefoot striking. The collision of the forefoot with the ground generates a significantly smaller impact force in comparison to striking heel first.[4] However, barefoot running leaves the foot unprotected from stepping on sharp objects. Although running barefoot may reduce the risk of running related injuries, it is important to take time while switching from running with shoes.

Beginning to run barefoot without reducing intensity or mileage of training can actually cause muscle or tendon injury. Changing one's style of running shoe or switching to barefoot running will most likely alter the foot strike pattern, meaning that the force of impact will be absorbed differently. Injuries are more likely to occur in novice barefoot runners. This may be a result of not yet having fully adapted to a new style of running, and therefore running with inconsistent technique. To measure this, a study was conducted involving runners who habitually run with a rearfoot strike while wearing shoes. Of the runners involved in the study, 32% used a heel strike pattern in initial attempts at running barefoot. Running barefoot while heel striking leads to increased muscle activation and impact accelerations.[5] The findings suggest that an inconsistency in running technique among novice barefoot runners may put them at a higher risk of injury in comparison to running with shoes.

Under some hypotheses, humans and their recent evolutionary ancestors may have needed to be able to run long distances in order to survive, and therefore natural selection would have favored traits that improve humans ability to run for long periods of time.

Endurance running hypothesis

According to the endurance running hypothesis, long distance running has been suggested to have played significant role in the lifestyle and evolution of early hominins. Before developing more advance hunting tools such as the bow and arrow, are thought to have used endurance running for scavenging and hunting. Persistence hunting is "a form of pursuit hunting in which [the hunter uses] endurance running during the midday heat to drive [prey] into hyperthermia and exhaustion so they can easily be killed".[6] Unlike many medium-to-large mammals that use panting as a form of evaporative cooling, hominins rely on sweating, allowing evaporation to occur on a much larger surface area. In this way, sweating results in better thermoregulation that allows the hominin to outlast the prey during the chase. This is one potential explanation for the loss of most body hair in humans. Those individuals with less body hair would be able to better thermoregulate while running to avoid overheating. For this species to exist under the endurance running hypothesis, running most likely did not result in the frequency of injuries that it does today, because such an injury to early hominins likely lead to starvation. This example would imply that recent ancestors of humans experienced selective pressure to adapt to barefoot running.

Minimalist footwear

Minimalist shoes are an alternative option that can be seen as an intermediate between running barefoot or with traditional running shoes, as they lack the high cushioned heels of traditional running shoes. These shoes are also designed to encourage forefoot striking.[7] One study observed the redistribution of mechanical work with fast speed running in minimalist shoes compared to conventional shoes in 26 trained runners. The results showed that running at a fast pace in minimalist shoes caused a statistically significant redistribution of work from the knee to the ankle joint.[8] Therefore, switching to a minimalist running shoe may be beneficial in preventing recurrence for runners who have experienced a knee injury in the past. However, the switch could also increase the risk of ankle and calf injuries. As with to barefoot running, runners who chose to switch to minimalist shoes should not start out at full training intensity.

References

- ↑ "Mechanisms of Selected Knee Injuries (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ↑ Radzak, Kara N.; Putnam, Ashley M.; Tamura, Kaori; Hetzler, Ronald K.; Stickley, Christopher D. (2017-01-01). "Asymmetry between lower limbs during rested and fatigued state running gait in healthy individuals". Gait & Posture. 51: 268–274. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.11.005. ISSN 1879-2219. PMID 27842295.

- ↑ "Achilles Tendinitis-OrthoInfo - AAOS". orthoinfo.aaos.org. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ↑ "Running Barefoot: Biomechanics of Foot Strike". barefootrunning.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- ↑ Lucas-Cuevas, Angel Gabriel; Priego Quesada, José Ignacio; Giménez, José Vicente; Aparicio, Inma; Jimenez-Perez, Irene; Pérez-Soriano, Pedro (2016-11-01). "Initiating running barefoot: Effects on muscle activation and impact accelerations in habitually rearfoot shod runners". European Journal of Sport Science. 16 (8): 1145–1152. doi:10.1080/17461391.2016.1197317. ISSN 1536-7290. PMID 27346636.

- ↑ Carrier, David R.; Kapoor, A. K.; Kimura, Tasuku; Nickels, Martin K.; Satwanti; Scott, Eugenie C.; So, Joseph K.; Trinkaus, Erik (1984-01-01). "The Energetic Paradox of Human Running and Hominid Evolution [and Comments and Reply]". Current Anthropology. 25 (4): 483–495. JSTOR 2742907.

- ↑ "Running Barefoot: Heel Striking & Running Shoes". www.barefootrunning.fas.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-03-01. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- ↑ Fuller, Joel T.; Buckley, Jonathan D.; Tsiros, Margarita D.; Brown, Nicholas A. T.; Thewlis, Dominic (2016-10-01). "Redistribution of Mechanical Work at the Knee and Ankle Joints During Fast Running in Minimalist Shoes". Journal of Athletic Training. 51 (10): 806–812. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-51.12.05. ISSN 1938-162X. PMC 5189234. PMID 27834504.