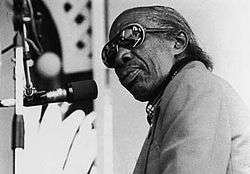

Professor Longhair

Henry Byrd redirects here. For those of a similar name, see Harry Byrd (disambiguation) or Henry Bird (disambiguation)

| Professor Longhair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Henry Roeland Byrd |

| Also known as | Fess |

| Born |

December 19, 1918 Bogalusa, Louisiana |

| Origin | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Died |

January 30, 1980 (aged 61) New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Genres | New Orleans blues, New Orleans R&B, Louisiana blues, boogie-woogie |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instruments | Vocals, piano |

| Years active | 1948–1980 |

Henry Roeland "Roy" Byrd (December 19, 1918 – January 30, 1980), better known as Professor Longhair or "Fess" for short, was a New Orleans blues singer and pianist. He was active in two distinct periods, first in the heyday of early rhythm and blues and later in the resurgence of interest in traditional jazz after the founding of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1970. His piano style has been described as "instantly recognizable, combining rumba, mambo, and calypso."[1]

The music journalist Tony Russell (in his book The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray) wrote that "The vivacious rhumba-rhythmed piano blues and choked singing typical of Fess were too weird to sell millions of records; he had to be content with siring musical offspring who were simple enough to manage that, like Fats Domino or Huey "Piano" Smith. But he is also acknowledged as a father figure by subtler players like Allen Toussaint and Dr. John."[2][3]

Biography

Byrd was born on December 19, 1918, in Bogalusa, Louisiana.[2] His distinctive style of piano playing was influenced by learning to play on an instrument that was missing some keys.[2] He left the city as a baby with his parents, who were most likely fleeing the racial tension surrounding the Bloody Bogalusa Massacre

He began his career in New Orleans in 1948. Mike Tessitore, owner of the Caldonia Club, gave Longhair his stage name.[4] Longhair first recorded in a band called the Shuffling Hungarians in 1949, creating four songs (including the first version of his signature song, "Mardi Gras in New Orleans") for the Star Talent record label. Union problems curtailed their release, but Longhair's next effort for Mercury Records the same year was a winner.[4] Throughout the 1950s, he recorded for Atlantic Records, Federal Records and local labels. Professor Longhair had only one national commercial hit, "Bald Head", in 1950, under the name Roy Byrd and His Blues Jumpers.[4] He also recorded his favorites, "Tipitina" and "Go to the Mardi Gras".[2] He lacked crossover appeal among white and wide audiences.[2] Yet, he is regarded (and was acknowledged) as being a musician who was highly influential for other prominent musicians, such as Fats Domino, Allen Toussaint and Dr. John.[5][6]

After suffering a stroke, Professor Longhair recorded "No Buts – No Maybes" in 1957.[4] He re-recorded "Go to the Mardi Gras" in 1959.[4] He first recorded "Big Chief" with its composer, Earl King, in 1964.

In the 1960s, Professor Longhair's career faltered.[2] He became a janitor to support himself and fell into a gambling habit.[7]

After a few years during which he disappeared from the music scene, Professor Longhair's musical career finally received "a well deserved renaissance" and wide recognition. He was invited to perform at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1971 and at the Newport Jazz Festival and the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1973.[2] His album The London Concert showcases work he did on a visit to the United Kingdom. That significant career resurrection is best marked by the seminal album "Professor Longhair - Live On The Queen Mary",[8] which was recorded on March 24, 1975, during an invited-only party hosted by Paul McCartney and Linda McCartney on board of the retired RMS Queen Mary.[9]

By the 1980s his albums, such as Crawfish Fiesta on Alligator Records and New Orleans Piano on Atlantic Records, had become readily available across America.[7] In 1974 He appeared on the PBS series Soundstage (with Dr. John, Earl King, and the Meters).[10]

In 1980 he co-starred (with Tuts Washington and Allen Toussaint) in the film documentary Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together which was produced and directed by the film maker Stevenson Palfi.[4] That documentary (which aired on public television in 1982, and was rarely seen ever since), plus a long interview with Fess (which was recorded two days before his sudden death), were included in the recent (2018) released project: "Fess Up".[11][12]

Professor Longhair died (in his sleep) of a heart attack while the filming of the documentary was under way (and before the live concert, which was planned to be its climax).[4][7] footage from his funeral was included in the documentry.[4]

Professor Longhair's manager through those renaissance years of his career was Allison Miner. Of which the Jazz producer George Wein was quoted saying: "Her devotion to Professor Longhair gave him the best years of his life".[13][14][15]

Accolades

Professor Longhair was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1981.[16]

In 1987 Professor Longhair was awarded a posthumous Grammy Award for his early recordings released as House Party New Orleans Style.[17]

He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992.[18]

In Culture

The B-side of the 1985 Paul McCartney single "Spies Like Us", entitled "My Carnival", credited to McCartney and Wings, was recorded in New Orleans and dedicated to Professor Longhair.

His song "Tipitina" was covered by Hugh Laurie on the 2011 CD album Let Them Talk. Laurie is a long-time fan, having used Longhair's "Go to the Mardi Gras" as the theme for the pilot episode of A Bit of Fry & Laurie. Laurie used to perform these two songs regularly during his world concert tours of 2011-2014 with The Copper Bottom Band, and on March 2013 paid tribute to Professor Longhair in a special concert on board of the RMS Queen Mary.[19]

The famous New Orleans music venue Tipitina's is named after one of Longhair's signature songs, and was created specifically as a venue for Longhair to perform in his aged years. Currently, a bust of Professor Longhair greets visitors upon entering the venue.[20]

Afro-Cuban elements

In the 1940s, Professor Longhair was playing with Caribbean musicians, listening a lot to Perez Prado's mambo records, and absorbing and experimenting with it all.[21] He was especially enamored with Cuban music. Longhair's style was known locally as "rumba-boogie".[22] Alexander Stewart stated that Longhair was a key figure bridging the worlds of boogie-woogie and the new style of rhythm and blues.[23] In his composition "Misery," Professor Longhair played a habanera-like figure in his left hand. The deft use of triplets in the right hand is a characteristic of Longhair's style.

Tresillo, the habanera, and related African-based single-celled figures have long been heard in the left hand-part of piano compositions by New Orleans musicians, such as Louis Moreau Gottschalk ("Souvenirs from Havana", 1859) and Jelly Roll Morton ("The Crave", 1910). One of Longhair's great contributions was the adaptation of Afro-Cuban two-celled, clave-based patterns in New Orleans blues. Michael Campbell stated, "Rhythm and blues influenced by Afro-Cuban music first surfaced in New Orleans. Professor Longhair's influence was ... far reaching. In several of his early recordings, Professor Longhair blended Afro-Cuban rhythms with rhythm and blues. The most explicit is 'Longhair's Blues Rhumba,' where he overlays a straightforward blues with a clave rhythm."[24] The guajeo-like piano part for the rumba-boogie "Mardi Gras in New Orleans" (1949) employs the 2-3 clave onbeat/offbeat motif.[25] The 2-3 clave time line is written above the piano excerpt for reference.

According to Dr. John (Malcolm John "Mac" Rebennack, Jr.), the Professor "put funk into music ... Longhair's thing had a direct bearing I'd say on a large portion of the funk music that evolved in New Orleans."[26] This is the syncopated, but straight subdivision feel of Cuban music (as opposed to swung subdivisions). Alexander Stewart stated that the popular feel was passed along from "New Orleans—through James Brown's music, to the popular music of the 1970s," adding, "The singular style of rhythm & blues that emerged from New Orleans in the years after World War II played an important role in the development of funk. In a related development, the underlying rhythms of American popular music underwent a basic, yet generally unacknowledged transition from triplet or shuffle feel to even or straight eighth notes.[27] Concerning funk motifs, Stewart stated, "This model, it should be noted, is different from a time line (such as clave and tresillo) in that it is not an exact pattern, but more of a loose organizing principle."[28]

Discography

Albums

- Rock 'n' Roll Gumbo (1974)

- Live on the Queen Mary (1978)

- Crawfish Fiesta (1980)

- The London Concert, with Alfred "Uganda" Roberts (1981) (also known as The Complete London Concert)

- The Last Mardi Gras (1982)

- Mardi Gras in New Orleans: Live 1975 Recording (1982) (also known as Live in Germany)

- House Party New Orleans Style: The Lost Sessions 1971–1972 (1987)

- Ball the Wall! Live at Tipitina's 1978 (2004)

Compilations

- New Orleans Piano (1972) (also known as New Orleans Piano: Blues Originals, Vol. 2)

- Mardi Gras In New Orleans 1949–1957 (1981)

- Mardi Gras in Baton Rouge (1991)

- Fess: The Professor Longhair Anthology (1993)

- Fess' Gumbo (1996)

- Collector's Choice (1996), half an album of hits

- Way Down Yonder in New Orleans (1997)

- All His 78's (1999)

- The Chronological Professor Longhair 1949 (2001)

- Tipitina: The Complete 1949–1957 New Orleans Recordings (2008)

- The Primo Collection (2009)

Filmography

- Dr. John's New Orleans Swamp (1974)

- Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together (1982), award-winning 76-minute documentary film featuring Professor Longhair, Tuts Washington, and Allen Toussaint

Quotation

Black or white, local or out-of-town, they all had Longhair's music in common. Just that mambo-rhumba boogie thing.

References

- ↑ Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues - A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers. p. 108. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 157. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- ↑ "Introduction". www.history-of-rock.com. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Biography by Bill Dahl". Allmusic.com. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Almost every musical history contains at least one crucial forebear whose inventions were too bold to translate to a broad audience, but who was nonetheless a profound influence on subsequent generations, and therefore changed the culture at an odd remove—a musician’s musician". In the nineteen-forties and fifties, that was Fess's stature. see The Still-Burning Piano Genius of Professor Longhair, an article by Amanda Petrusich of May 10, 2018, published in The New Yorker, retrieved September 9, 2018

- ↑ "It's echoed in my songs, whether you could hear it or not - as for the licks themselves, but my heart always have some Professor Lonhair in it, in probably everything I do..." Allen Toussaint explains (and demonstrates) to Sound Opinions the influence of Professor Longhair on his music, Published at the formal YouTube channel of Sound Opinions

- 1 2 3 Oliver (ed.), Paul (1989). The Blackwell Guide to Recorded Blues. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Publisher. pp. 280–281. ISBN 0-631-18301-9.

- ↑ Professor Longhair - Live On The Queen Mary at Allmusic website

- ↑ Professor Longhair, short biography at the Encyclopaedia Britannica website

- ↑ Dr. John (January 6, 2016). "Big Chief with Professor Longhair & The Meters" – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Fess Up" - Information, excerpts and reviews from the film maker's website

- ↑ "Professor Longhair – Fess Up (2-DVD Set w 38-pg Book) - Louisiana Music Factory". www.louisianamusicfactory.com.

- ↑ "The Interview with Professor Longhair — Fess Up". palfifilms.com.

- ↑ Miner talked about Professor Lonhair's enormous contribution to the R&B music and musicians in the 40s and 50s of the 20th century ("...He developed a style that became the New Orleans sound, and everyone, you know, played it... the essence of what New Orleans music is, is what Professor Longhair brought to it... "), in the short documentry "Reverence: A Tribute to Allison Miner"(Produced and directed by Amy Nesbitt). In that documentry Miner also recalled how the resurrection of Fess' career came about: "...Professor Longhair had not played publicaly for over ten years, he just had not played at all, and he came out of retirement for the festival. Quint (Quint Davis, her co-producer of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival) found him at the one stop record shop on Rampart street... We had four stages then, in the corners of Congress Square, and Fess started playing and everything stopped and everyone went over to the stage where he was... everything just stopped -- and the whole festival moved over to that stage."

- ↑ see also Professor Longhair at 100: New Orleans Jazz Fest, new DVD celebrate piano legend's legacy, an article by Keith Spera of April 28, 2018 in The New Orleans Advocate (retrieved September 10, 2018)

- ↑ Professor Longhair, in the list of BHOF inductees at the Blues Foundation website

- ↑ Professor Longhair at the Grammy Award website

- ↑ Professor Longhair at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame website

- ↑ see Hugh Laurie salutes Professor Longhair in PBS special 'Live on the Queen Mary, an article (which includes an interview with Laurie of his long time hero), published on August 3, 2013 in Nola website (retrieved September 11, 2018). That concert was recorded and featured as a PBS special (later on also distributed as a DVD set) under the title: "Hugh Laurie: Live on the Queen Mary" (a clear homage to the seminal live album recorded by Fess at the very same place on March 1975)

- ↑ Tipitina's history original web page, as reflected in the Internet Archive (retrieved October 13, 2018)

- ↑ Palmer, Robert (1979). A Tale of Two Cities: Memphis Rock and New Orleans Roll. Brooklyn. p. 14.

- ↑ Stewart, Alexander (2000). "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music." Popular Music, vol. 19, no. 3, Oct. 2000, p. 298.

- ↑ Stewart (2000), p. 297.

- ↑ Campbell, Michael; Brody, James (2007). Rock and Roll: An Introduction. Schirmer. p. 83. ISBN 0-534-64295-0.

- ↑ Kevin Moore: "There are two common ways that the three-side [of clave] is expressed in Cuban popular music. The first to come into regular use, which David Peñalosa calls 'clave motif,' is based on the decorated version of the three-side of the clave rhythm. By the 1940s [there was] a trend toward the use of what Peñalosa calls the 'offbeat/onbeat motif.' Today, the offbeat/onbeat motif method is much more common." Moore (2011). Understanding Clave and Clave Changes. Santa Cruz, Calif.: Moore Music/Timba.com. p. 32. ISBN 1466462302.

- ↑ Dr. John, quoted by Stewart (2000), p. 297.

- ↑ Stewart (2000), p. 293.

- ↑ Stewart (2000), p. 306.

- ↑ Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music. Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 161. ISBN 9780823078691.

External links

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

- Allmusic – biography

- Professor Longhair at Myspace

- Henry Roeland Byrd at Find a Grave

- Professor Lonhair Biography, originally published at the All About Jazz website, as reflected from the Internet Archive