Rotoscoping

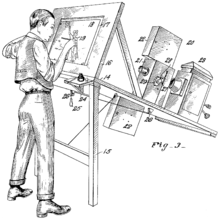

Rotoscoping is an animation technique that animators use to trace over motion picture footage, frame by frame, to produce realistic action. Originally, animators projected photographed live-action movie images onto a glass panel and traced over the image. This projection equipment is referred to as a rotoscope, developed by Polish-American animator Max Fleischer. This device was eventually replaced by computers, but the process is still called rotoscoping.

In the visual effects industry, rotoscoping is the technique of manually creating a matte for an element on a live-action plate so it may be composited over another background.[1][2]

Technique

Rotoscoping has often been used as a tool for visual effects in live-action movies. By tracing an object, the moviemaker creates a silhouette (called a matte) that can be used to extract that object from a scene for use on a different background. While blue- and green-screen techniques have made the process of layering subjects in scenes easier, rotoscoping still plays a large role in the production of visual effects imagery. Rotoscoping in the digital domain is often aided by motion-tracking and onion-skinning software. Rotoscoping is often used in the preparation of garbage mattes for other matte-pulling processes.

Rotoscoping has also been used to create a special visual effect (such as a glow, for example) that is guided by the matte or rotoscoped line. A classic use of traditional rotoscoping was in the original three Star Wars movies, where the production used it to create the glowing lightsaber effect with a matte based on sticks held by the actors. To achieve this, effects technicians traced a line over each frame with the prop, then enlarged each line and added the glow.

History

Predecessors

Eadweard Muybridge had some of his famous chronophotographic sequences painted on glass discs for the zoopraxiscope projector that he used in his popular lectures between 1880 and 1895. The first discs were painted on the glass in dark contours. Discs made between 1892 and 1894 had outlines drawn by Erwin Faber photographically printed on the disc and then coloured by hand, but these discs were probably never used in the lectures.[3]

By 1902, Nuremberg toy companies Gebrüder Bing and Ernst Plank were offering chromolithographed film loops for their toy kinematographs. The films were traced from live-action film footage.[4]

Early works and Fleischer's exclusivity

The rotoscope technique was invented by Poland-born animator Max Fleischer in 1915, and used in his groundbreaking Out of the Inkwell animated series (1918–1927). It was known simply as the "Fleischer Process" on the early screen credits, and was essentially exclusive to Fleischer for several years. The live-movie reference for the character, later known as Koko the Clown, was performed by his brother (Dave Fleischer) dressed in a clown costume.[5]

Originally conceived as a short-cut to animating, the rotoscope process proved time consuming due the precise and laborious nature required in tracing. Rotoscoping is achieved by two methods, rear projection and front surface projection. In either case, the results can have slight deviations from the true line due to the separation of the projected image and the surface used for tracing. Misinterpretations of the forms cause the line to wiggle, and the roto tracings must be reworked over an animation disc, using the tracings as a guide where consistency and solidity are important.

Fleischer ceased to depend on the rotoscope for fluid action by 1924, when Dick Huemer became the animation director and brought his animation experience from his years on the Mutt and Jeff series. Fleischer returned to rotoscoping in the 1930s for referencing intricate dance movements in his Popeye and Betty Boop cartoons. The most notable of these are the dance routines originating from jazz performer Cab Calloway in Minnie the Moocher (1932), Snow White (1933), and The Old Man of the Mountain (1933). In these examples, the roto tracing were used as a guide for timing and positioning, while the cartoon characters of different proportions were drawn to conform to those positions.[6]

Fleischer's last applications of rotoscope were for the realistic human animation required for the lead character—among others—in Gulliver's Travels (1939), and the human characters in his last feature, Mr. Bug Goes to Town (1941). His most effective use of rotoscoping was in the action-oriented film noir Superman series of the early 1940s, where realistic movement was achieved on a level unmatched by conventional cartoon animation.

Contemporary uses of the rotoscope and its inherent challenges have included surreal effects in music videos such as Klaatu's "Routine Day", A-ha's "Take On Me", Kansas' "All I Wanted", the live performance scenes in Dire straits' "Money for Nothing", and the animated TV series Delta State.

Uses by other studios

Fleischer's patent expired by 1934, and other producers could then use rotoscoping freely. Walt Disney and his animators used the technique in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs during 1937.[7]

Leon Schlesinger Productions, which produced the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons for Warner Bros., occasionally used rotoscoping. The 1939 MGM cartoon "Petunia Natural Park" from The Captain and the Kids featured a rotoscope version of Jackie.

Rotoscoping was used extensively in China's first animated feature film, Princess Iron Fan (1941), which was released under very difficult conditions during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

The technique was used extensively in the Soviet Union from the late 1930s to the 1950s, where it was known as "Éclair" (эклер in Russian) and its historical use was enforced as a realization of Socialist Realism. Most of the movies produced with it were adaptations of folk tales or poems—for example, The Night Before Christmas or The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish. Only during the early 1960s, after the "Khrushchev Thaw", did animators start to explore very different aesthetics.

The makers of the Beatles' Yellow Submarine used rotoscoping in the "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" sequence. Director Martin Scorsese used rotoscoping to remove a large chunk of cocaine hanging from Neil Young's nose in his rock documentary The Last Waltz.[8][9][10]

Ralph Bakshi used rotoscoping extensively for his animated features Wizards (1977), The Lord of the Rings (1978), American Pop[1] (1981), and Fire and Ice (1983). Bakshi first used rotoscoping because 20th Century Fox refused his request for a $50,000 budget increase to finish Wizards; he resorted to the rotoscope technique to finish the battle sequences.[11][12]

Rotoscoping was also used in Heavy Metal[1] (1981), What Have We Learned, Charlie Brown? (1983) and It's Flashbeagle, Charlie Brown (1984); three of A-ha's music videos, "Take On Me" (1985), "The Sun Always Shines on T.V." (1985), and "Train of Thought" (1986); Don Bluth's The Secret of NIMH (1982), An American Tail (1986), Harry and the Hendersons (closing credits), Titan A.E. (2000); and Nina Paley's Sita Sings the Blues (2008).

During 1994, Smoking Car Productions invented a digital rotoscoping process to develop its critically acclaimed adventure video game The Last Express. The process was awarded U.S. Patent 6,061,462, Digital Cartoon and Animation Process. The game was designed by Jordan Mechner, who had used rotoscoping extensively in his previous games Karateka and Prince of Persia.

During the mid-1990s, Bob Sabiston, an animator and computer scientist veteran of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab, developed a computer-assisted "interpolated rotoscoping" process, which he used to make his award-winning short movie "Snack and Drink". Director Richard Linklater subsequently employed Sabiston and his proprietary Rotoshop software in the full-length feature movies Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006).[13] Linklater licensed the same proprietary rotoscoping process for the look of both movies. Linklater was the first director to use digital rotoscoping to create an entire feature movie. Additionally, a 2005–08 advertising campaign by Charles Schwab used Sabiston's rotoscoping work for a series of television commercials, with the tagline "Talk to Chuck". The Simpsons used rotoscope as a couch gag in the episode Barthood, with Lisa describing it as "a noble experiment that failed".

During 2013, the anime The Flowers of Evil used rotoscoping to produce a look that differed greatly from its manga source material. Viewers criticized the show's shortcuts in facial animation, its reuse of backgrounds, and the liberties it took with realism. Despite this, critics lauded the movie, and the website Anime News Network awarded it a perfect score for initial reactions.[14]

In early 2015, an anime film titled The Case of Hana & Alice (animated prequel to the 2004 live-action film, Hana and Alice) was entirely animated with rotoscoping, but it was far better-received than The Flowers of Evil, with critics praising its rotoscoping. In 2015, Kowabon, a short-form horror anime series using rotoscoping, aired on Japanese TV.

See also

- Rotoshop is also referred to as interpolated rotoscoping

- Motion capture

- List of rotoscoped works

References

- 1 2 3 Maçek III, J.C. (2012-08-02). "'American Pop'... Matters: Ron Thompson, the Illustrated Man Unsung". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 2013-08-24.

- ↑ "Through a 'Scanner' dazzlingly: Sci-fi brought to graphic life" USA TODAY, August 2, 2006 Wednesday, LIFE; Pg. 4D WebLink Archived 2011-12-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.stephenherbert.co.uk/muy%20blog3.htm#part15 Archived 2018-01-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Litten, Frederick S. (2013). "Shōtai kenkyū nōto: Nihon no eigakan de jōei sareta saisho no (kaigai) animēshon eiga ni tsuite" 招待研究ノート:日本の映画館で上映された最初の(海外)アニメーション映画について [On the Earliest (Foreign) Animation Shown in Japanese Cinemas]. The Japanese Journal of Animation Studies (in Japanese). 15 (1A): 9–11.

- ↑ US patent 1242674, Max Fleischer, "Method of producing moving-picture cartoons", issued 1917-10-09

- ↑ Pointer, Ray (2016). The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer: American Animation Pioneer. Mcfarland. ISBN 9781476663678. OCLC 948547933.

- ↑ "Reviving an ancient art" The Times (London), August 5, 2006, FEATURES; The Knowledge; Pg. 10. Weblink, see bottom of page

- ↑ Selvin, Joel (2002-04-22). "The day the music lived". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- ↑ Lawson, Terry (2002-04-26). "'The Last Waltz' rekindles Band fervor". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on August 25, 2003. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ "The 50 Worst Rock Fails Of All Time". Complex. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Ralph Bakshi: The Wizard of Animation making-of documentary.

- ↑ Bakshi, Ralph. Wizards DVD, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2004, audio commentary. ASIN: B0001NBMIK

- ↑ La Franco, Robert (March 2006). "Trouble in Toontown". Wired. 14 (3). ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 2008-10-27. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- ↑ "The Spring 2013 Anime Preview Guide". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 2013-04-21. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

External links

- Description of "Digital cartoon and animation process" (Digital rotoscoping) Patent