Ronin (film)

| Ronin | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Frankenheimer |

| Produced by | Frank Mancuso Jr. |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | J.D. Zeik |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Elia Cmiral |

| Cinematography | Robert Fraisse |

| Edited by | Tony Gibbs |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $55 million[4] |

| Box office | $70.7 million[4] |

Ronin is a 1998 American action thriller film written by John David Zeik and David Mamet (using the pseudonym Richard Weisz) and directed by John Frankenheimer. It stars Robert De Niro, Jean Reno, Natascha McElhone, Stellan Skarsgård, Sean Bean, and Jonathan Pryce. In the story, a team of former special operatives is hired to steal a mysterious, heavily guarded briefcase while navigating a maze of shifting loyalties. The film is noted for its realistic car chases in Nice and Paris and its convoluted plot, using the case as a MacGuffin.

Frankenheimer signed in 1997 to direct Zeik's screenplay, which Mamet rewrote significantly to expand De Niro's role and develop plot details. Principal photography was done in France from November 3, 1997 to March 3, 1998 and was supervised by the French cinematographer Robert Fraisse. Vehicle stunts were coordinated and performed by professional race-car drivers. Elia Cmiral scored the film, his first for a major studio.

Ronin premiered at the 1998 Venice Film Festival before its general release on September 25. Performing moderately well at the box office, the film had a warm critical reception. Considered a return to form for Frankenheimer, it was his last well-received feature film.[5] Film critic and historian Stephen Prince called Ronin Frankenheimer's "end-of-career masterpiece".[6] The car chases, which were favorably compared to Bullitt and The French Connection,[7][8] made several media outlets' lists as some of the best portrayed in film.

Plot

At a bistro in Montmartre, Irish operative Deirdre meets with former special operatives-turned-mercenaries Sam and Larry (Americans) and Vincent (a Frenchman). She takes them to a warehouse where fellow mercenaries (the Englishman Spence and the German Gregor) are waiting, and briefs them on their mission: to attack a heavily armed convoy and steal a large metallic briefcase, the contents of which are never revealed. As the team prepares, Deirdre meets with handler Seamus O'Rourke, who says that the Russian mafia is bidding for the case and the team must intervene. After Spence is exposed as a fraud by Sam and dismissed, the others leave for Nice. Sam and Deirdre are attracted to each other during a stakeout. On the day of the sale, Deirdre's team ambushes the convoy at La Turbie and pursue the survivors to Nice. After a gunfight at the port, Gregor steals the case and disappears.

He sells the case to the Russians, but is forced to kill his contact when he betrays him. Gregor contacts Mikhi (the Russian mobster in charge of the deal), and makes him agree to another meeting. The team tracks Gregor through one of Sam's CIA contacts and corners him in the Arles Amphitheatre, where he is meeting two of Mikhi's men. Gregor flees and is captured by Seamus, who kills Larry and escapes with Deirdre. Sam is shot while saving Vincent's life and is brought to a villa in Les Baux-de-Provence owned by Vincent's friend, Jean-Pierre. After removing the bullet and letting Sam recuperate, Vincent asks Jean-Pierre to help them find Gregor and the Irishmen.

In Paris, Gregor is brutally interrogated into leading Seamus and Deirdre to a post office where they retrieve the case. Sam and Vincent pursue them in a high-speed chase, which ends when Vincent shoots Deirdre's tire and sends her car over an overpass under construction. When Sam and Vincent fire at him, Gregor takes cover behind the flipped car (which is set ablaze by the gunfire). Gregor flees with the case, while road workers rescue Deirdre and Seamus from the burning vehicle. Sam and Vincent decide to track down the Russians and learn from one of Jean-Pierre's contacts that they are involved with figure-skater Natacha Kirilova (Mikhi's girlfriend), who is appearing at Le Zénith.

During his girlfriend's performance that night Mikhi meets with Gregor, who says that a sniper in the arena will shoot Natacha if Mikhi betrays him. Mikhi kills Gregor and leaves with the case, letting the sniper kill Natacha. Sam and Vincent follow the panicked crowd out of the arena in time to see Seamus shoot Mikhi and steal the case. Sam runs ahead and finds Deirdre waiting in the getaway car; he tells her to leave, revealing himself as a CIA agent pursuing Seamus and not the case. Deirdre drives away, forcing Seamus to run back to the arena with Sam in pursuit. Seamus ambushes Sam, and is fatally shot by Vincent.

Sam and Vincent later talk in the bistro where they first met, while a radio broadcast announces that a peace agreement was reached between Sinn Féin and the British government (partially as a result of Seamus' death). Sam looks toward the door expectantly, but Vincent tells him that Deirdre will not be coming back. Sam drives off with his CIA contact, and Vincent pays the bill and leaves.

Cast

- Robert De Niro as Sam:

An American mercenary formerly associated with the CIA.[9] According to director John Frankenheimer, De Niro "was always dream casting" for the film.[10] - Jean Reno as Vincent:

A French gunman who befriends Sam.[11][12] Frankenheimer sought to establish the friendship between Reno's and De Niro's characters, since he considered it pivotal to the story and wanted to strengthen the off-screen bond between the actors.[10] - Natascha McElhone as Deirdre:

An IRA operative commissioned to steal a briefcase by Seamus O'Rourke.[12][13] McElhone had a dialect coach on set to help her speak with a Northern Irish accent.[10] McElhone said she was thrilled to do the role because she got to portray a character that moved the action forward.[14] - Sean Bean as Spence:

An English firearms specialist.[15] During production, Frankenheimer did not know what the future held for the character and thought about having him killed by shooting him off-screen (after the team drove out of the warehouse) or snatched from a Parisian street into a van driven by the IRA. Ultimately, he dismissed him from the team.[10] Bean described the character as egotistic and "a little bit out of his depth".[14] - Stellan Skarsgård as Gregor:

A German computer specialist formerly associated with the KGB.[12] A fan of Skarsgård, Frankenheimer praised the Swedish actor for "bring[ing] so much to the role."[10] Of the character's backstory, Skarsgård suggested that Gregor was abandoned by his wife and son, for which he became "quite suicidal and cold".[14] - Jonathan Pryce as Seamus O'Rourke:

A rogue operative in pursuit of the case through Deirdre.[12][13] Like McElhone, the Welsh Pryce was coached to hone his Northern Irish accent.[10] - Skipp Sudduth as Larry:

Another American and the team's designated driver.[15] Sudduth, who had appeared in Frankenheimer's George Wallace (1997),[16] performed most of his driving stunts.[10] - Michael Lonsdale as Jean-Pierre:

Vincent's friend and colleague whose pastime is creating miniatures.[17] Frankenheimer intended to make the character a miniature artist, partially due to his own love of creating miniatures.[10] The film was Lonsdale's third collaboration with Frankenheimer.[16] - Katarina Witt as Natacha Kirilova:

A Russian figure skater.[6][9] Witt wanted to become an actress after a career as a figure skater; Frankenheimer had always wanted to shoot an ice-skating scene, and cast her in the film.[10] - Féodor Atkine as Mikhi:

Leader of the Russian mafia[13]

Production

Frankenheimer, who signed to direct Ronin in 1997,[15] agreed that he "could do it rather well. It seemed to fit into things that I know what to do."[14] He explained that choosing the project gave him the opportunity to apply his broad knowledge and understanding of France, especially Paris, in which he resided for many years:[10] "I would not have been able to do the film nearly as well anywhere else".[14] His films The Train (1963), Grand Prix (1966), Impossible Object (1973), and French Connection II (1975) were shot in France.[8] According to Frankenheimer, French authorities helped him circumvent a strict Paris ordinance prohibiting film productions from firing guns in the city which was enacted after many civilian complaints about gunfire produced by production crews. Two factors influenced the decision: officials wanted an American action film (like Ronin) to be filmed in Paris, since few had been shot since the law was passed, and they wanted to boost France's reputation as a filming location.[10]

Many of Ronin's principal crew members had worked with Frankenheimer on television films: editor Tony Gibbs on George Wallace, set designer Michael Z. Hanan on George Wallace and The Burning Season (1994), and costume designer May Routh on Andersonville (1996).[19] Frankenheimer chose French cinematographer Robert Fraisse to help him achieve the look and style he envisioned for the film. Fraisse impressed Frankenheimer with his work on the police thriller Citizen X (1995), which convinced the director that Fraisse could handle the more than 2,000 setups he planned for Ronin.[8] Frank Mancuso Jr. was the film's producer.[2]

Screenplay

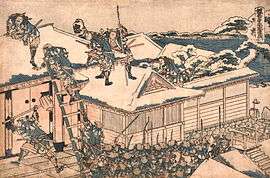

Film newcomer John David Zeik[20] conceived the idea for Ronin after reading James Clavell's novel, Shōgun, at age 15.[19] It gave him background on rōnin (masterless samurai), which he incorporated into a screenplay years later. On choosing France as the story's key location, Zeik said: "Many years in Nice, I stared into the sun and saw the silhouettes of five heavily-armed gendarmes crossing the Promenade des Anglais. That image made me realize that I wanted to set the film in France."[19]

According to Zeik's attorney, playwright David Mamet was brought in just before production to expand De Niro's role and add a female love interest; although Mamet rewrote several scenes, his contributions were minor. However, Frankenheimer called Mamet's contributions more significant: "The credits should read: 'Story by J.D. Zeik, screenplay by David Mamet'. We didn't shoot a line of Zeik's script."[20] When he learned that he would have to share screenwriting credit with Zeik, Mamet insisted on being credited with the pseudonym Richard Weisz (since he had decided earlier to attach his name only to projects where he was the sole writer).[20] A factor which attracted Frankenheimer to direct was the abundant subtext in Mamet's script.[10]

Filming and cinematography

Ronin was produced on a budget of $55 million.[4] Principal photography lasted 78 days,[8] beginning on November 3, 1997 in an abandoned workshop at Aubervilliers.[22] Scenes at Porte des Lilas and the historic Arles Amphitheatre were filmed in November. The crew then shot footage at the Hotel Majestic in Cannes, La Turbie, and Villefranche.[22] Production was suspended for Christmas on December 19 and resumed on January 5, 1998 at Épinay, where the crew built two interior sets on sound stages: one for the bistro in Montmartre and another for the rural farmhouse,[22] both of which also have exterior location shots.[10] The climactic scene, with a panicked crowd at Le Zénith, required about 2,000 extras supervised by French casting director Margot Capelier.[10] Filming wrapped on March 3, 1998 at La Défense.[22]

Because there were no second unit director and cameraman to film the action scenes, Frankenheimer and cinematographer Robert Fraisse supervised them for an additional 30 days after the main unit wrapped.[8][23] The first car-chase scene was shot in La Turbie and Nice (on Old Nice's narrow streets); the rest were filmed in areas of Paris including La Défense and the Pont du Garigliano.[22][24] Tunnel scenes were shot at night because it was impossible to block tunnel traffic during the day.[25] The freeway chase, where the actors dodge oncoming vehicles, was filmed in four hours on a closed road.[25]

Frankenheimer's affinity for depth of field compelled him to shoot the film entirely with wide-angle lenses (ranging from 18 to 35 mm) and the Super 35 format, both of which allowed more of the scene to be included in each shot.[10][21] The director also avoided bright primary colors to preserve a first-generation-of-film quality.[10] He advised the actors and extras not to wear bright colors and processed the film using Deluxe's Color Contrast Enhancement (CCE), "a silver-retention method of processing film that deepens blacks, reduces color, and heightens the visible appearance of film grain".[10][26] Fraisse said that he used a variety of cameras to facilitate Frankenheimer's demands, including Panaflexes for dialogue scenes and Arriflex 435s and 35-IIIs for the car chases.[8] Steadicam (a camera stabilizer used for half the shoot) was operated by the director's longtime collaborator, David Crone.[8] According to Frankenheimer, a total of 2,200 shots were filmed.[10]

Stunts

Frankenheimer avoided special effects in the car-chase scenes, previsualized them on storyboards and used the same camera mounts as those on Grand Prix.[10] He placed the actors inside the cars, which were driven by Formula One driver Jean-Pierre Jarier and high-performance drivers Jean-Claude Lagniez and Michel Neugarten at speeds of up to 100 mph (160 km/h).[8] The actors had enrolled at a high-performance driving school before production began.[10] According to Lagniez (the car-stunt coordinator), it was a priority not to cheat the speed by adjusting the frame rate: "When you do, it affects the lighting. It is different at 20 frames than at 24 frames."[25] However, Fraisse said: "Sometimes, but not very often, we did shoot at 22 frames per second, or 21."[8] Point-of-view shots from cameras mounted below the cars' front fender were used to heighten the sense of speed.[10][27]

For the final chase scene (which used 300 stunt drivers),[10] the production team bought four BMW 535is and five Peugeot 406s;[lower-alpha 1] one of each was cut in half and towed by a Mercedes-Benz 500 E while the actors were in them.[10] Right-hand drive versions of the cars were also purchased; a dummy steering wheel was installed on the left side (where the actors pretended to drive), while the stunt drivers drove the speeding vehicles.[10][25] The final chase had very little music, because Frankenheimer felt that music and sound effects do not mesh well. Sound engineer Mike Le Mare recorded all the film's cars on a racetrack, mixing them later in post-production.[10]

Frankenheimer refused to film the gunfights in slow motion, believing that onscreen violence should be depicted in real time.[10] A former member of the Special Air Service was on standby, sharing their experiences of weapon-handling and military tactics with the actors.[10] The physical stunts were coordinated by Joe Dunne.[2]

Style and inspiration

The film's title was derived from the Japanese legend of rōnin, samurai whose leader was killed; disgraced, with no one to serve, they roamed the countryside as mercenaries and bandits to regain a sense of purpose.[29] In Frankenheimer's film, the rōnin are former intelligence operatives who are unemployed at the end of the Cold War; devoid of purpose, they become highly-paid mercenaries. Michael Lonsdale's character elaborates on the analogy in an anecdote about the forty-seven rōnin told with miniatures, comparing the film's characters to the 18th-century rōnin.[30] In his essay, "Action and Abstraction in Ronin", Stephen Prince wrote that the rōnin metaphor explores themes of "service, honor, and obligation to complex ways by showing that service may entail betrayal and that honor may be measured according to disparate terms".[31] According to Stephen B. Armstrong, "Arguably Frankenheimer uses this story to highlight and contrast the moral and social weakness that characterize the band of rōnin in his film."[29]

Ronin's elusive briefcase has been cited as an example of a MacGuffin, defined by filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock as an object to which characters are drawn (although its value is not equally important to each of them).[12][32][33] Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert jokingly suggested that its content is identical to that of the equally-mysterious case in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994).[32][lower-alpha 2] Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune called Ronin an homage to The French Connection (1971), The Parallax View (1974), and Three Days of the Condor (1975): thriller films known for their lack of visual effects.[33] Maitland McDonagh of TV Guide agreed, also comparing the film to The Day of the Jackal (1973).[13] Wilmington noted similarities between Ronin's opening scene and that of Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs (1992), where a group of professional killers (who have not met before) assemble.[33] According to Armstrong, the film's plot observes the conventions of heist films.[29]

Frankenheimer employed a hyperrealistic aesthetic in his films "to make them look realer than real, because reality by itself can be very boring," and saw them as having a tinge of semi-documentary.[10] He credited Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers (1966), a film he considered flawless and more influential than any other he had seen, with inspiring this style.[10] According to Prince, "Frankenheimer's success at working in this realist style, avoiding special effects trickery, places the car chase in Ronin in the same rarefied class as the celebrated chase in Bullitt (1968)".[35] The director credited the Russian film, The Cranes Are Flying (1957), with inspiring invisible cuts in Ronin. On the film's DVD audio commentary, Frankenheimer notes a wipe during the opening scenes (made by two extras walking across the frame) which becomes a tracking shot of Jean Reno entering the bistro. His intention for the cut was to conceal the fact that the bistro's interior was a set; its exterior was filmed on location.[10]

Alternate endings

Frankenheimer shot two versions of the film's ending. In the first, Deirdre (McElhone) waits on the stairs next to the bistro and considers joining Sam (De Niro) and Vincent (Reno). Deciding against it, she walks up the stairs. As she gets into her car, she is dragged into a van by men from the IRA who call her a traitor; it is implied that she is later killed. Sam and Vincent finish their conversation and depart, completely unaware of what has just happened. Although Frankenheimer said that the test audience "hated" the ending because they did not want to see Deirdre die, he thought it "really worked."[10] In the second ending, Deirdre walks to her car after Sam and Vincent leave the bistro. This, too, was rejected because it verged on being "too Hollywood" (hinting at a sequel). Ultimately, Frankenheimer yielded to the test audience's response with a compromise ending: "... With the tremendous investment MGM/UA had in this movie, you have to kind of listen to the audience".[10]

Music

Jerry Goldsmith was originally commissioned to compose the score for Ronin, but left the project.[36][37] MGM executive vice president for music Michael Sandoval assembled an A-list to replace Goldsmith.[36] From Sandoval's three choices, Frankenheimer hired Czech composer Elia Cmiral[10][36] (who recalled that he "was far away from being even a 'B' composer at that time").[37] Cmiral attended a private screening of the film's final version and considered its main theme, which (at Frankenheimer's behest) would incorporate qualities of "sadness, loneliness, and heroism."[36] To achieve this, Cmiral performed with the duduk: an ancient, double-reed woodwind flute which originated in Armenia.[38] Cmiral sent a demo to Frankenheimer (who "loved" it), and was signed as the film's composer.[36] "Ronin Theme" was used for the opening scenes.[36][39]

Ronin, Cmiral's first score for a major studio,[38] was recorded in seven weeks at CTS Studio in London.[36][39] It was orchestrated and conducted by Nick Ingman, edited by Mike Flicker, and recorded and mixed by John Whynot.[36] Varèse Sarabande released the soundtrack album on compact disc in September 1998.[39] For AllMusic, Jason Ankeny rated the album 4.5 out of 5 and called it a "profoundly visceral listening experience, illustrating an expert grasp of pacing and atmosphere."[39]

Release

The film had its world premiere at the 1998 Venice Film Festival on September 12,[40] before a wide release on September 25.[41] Ronin fared moderately well at the box office;[42] it was the second highest-grossing film in its United States over its opening weekend, grossing $16.7 million (behind the action comedy Rush Hour's $26.7 million) at 2,643 locations.[43] The film dropped to fifth place on its second weekend and seventh on its third, grossing $7.2 million and $4.7 million at 2,487 locations.[44] It dropped further until its sixth weekend, when it grossed $1.1 million (13th place) at 1,341 locations.[44] The film ended its theatrical run with a gross of $41.6 million in the U.S. and Canada and $70.7 million worldwide.[4][41] It was 1998's 11th-highest-grossing R-rated film.[45]

MGM Home Entertainment released Ronin on a two-disc DVD in February 1999, in widescreen or pan and scan and Dolby Digital 5.1 sound.[46] The DVD contains the alternate ending, and audio commentary by John Frankenheimer who discusses the film's production history.[47] MGM released a special edition DVD of the film in October 2004 and a two-disc collector's edition in May 2006, both with additional cast and crew interviews.[46]

It was released on Blu-ray in February 2009 with its theatrical trailer.[48] Arrow Video released a special edition Blu-ray in August 2017, with a 4K resolution restoration from the original camera negative which was supervised and approved by cinematographer Robert Fraisse.[49] Arrow's Blu-ray has a combination of archival bonus features originally appearing on the MGM special edition DVD,[50] plus "Close Up" (in which Fraisse reminisces about his early cinematography career and briefly discusses his involvement on Ronin) and "You Talkin' To Me?" (Quentin Tarantino's admiration for Robert De Niro).[51]

Critical reception

—Stephen Prince, 2011[6]

Reviews of Ronin were positive.[15] Critics praised its ensemble cast, and often singled out Robert De Niro.[2][9][32][52] Although Todd McCarthy in Variety credited De Niro with sustaining the film,[2] a reviewer from the Chicago Reader disagreed.[53] The film's action scenes (particularly the car chases) were generally praised,[2][15][52] with Janet Maslin in The New York Times calling them "nothing short of sensational."[52] However, the scenes were criticized by The Washington Post for their length[11] and by McCarthy for their excessive jump cuts.[2] Robert Fraisse's cinematography was generally praised,[2][9] with Michael Wilmington in the Chicago Tribune calling it superficially attractive and entertaining.[33] Although the plot was criticized by the Chicago Reader as dull and The Washington Post as derivative,[11][53] Wilmington called it a "familiar but taut tale."[33] Some reviewers singled out the espionage scene in which De Niro and Natascha McElhone pose as tourists and photograph their targets at a Cannes hotel as one of the film's best.[2][11]

Critics also evaluated Frankenheimer, since the broad acclaim he received with the political thriller The Manchurian Candidate (1962) established him as a director.[9][32][33] Many said that he was influenced by the works of fellow filmmaker (and close friend) Jean-Pierre Melville, particularly Melville's neo-noir film Le Samouraï (1967),[42][54] but McCarthy wrote that Ronin lacked Melville's "world-weary, existential ennui".[2] Some critics said that Ronin signaled a return to form for Frankenheimer[18][55] after consecutive Emmy Awards for the television films Against the Wall (1994), The Burning Season, Andersonville and George Wallace and a career downturn due to the director's struggle with alcoholism during the 1970s and 1980s.[5][9] Ronin was Frankenheimer's last well-received feature film;[5] Wilmington called it the director's best theatrical film in decades, despite lacking The Manchurian Candidate's "blazing invention",[33] and Stephen Prince called the film his "end-of-career masterpiece."[6]

The review-aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives Ronin a 68% approval rating from 62 published reviews (a weighted average of 6.3 out of 10) and the consensus, "This is comparable to French Connection with great action, dynamic road chase scenes, and solid performances."[56] The film has a score of 67 out of 100 on Metacritic (based on 23 critics), indicating "generally favorable reviews".[57] Audiences polled by CinemaScore during Ronin's opening weekend gave the film an average grade of C+ on an A+ to F scale.[58] Its car chases made several media outlets' lists as the best depicted on film, including CNN (No. 2),[59] Time (No. 12),[60] The Daily Telegraph (No. 10),[61] PopMatters and IGN (No. 9),[62][63] Screen Rant (No. 8),[64] Business Insider (No. 3) and Collider.[65][66] Screen Rant ranked Ronin No. 1 on its "12 Best Action Movies You've Never Heard Of" list.[67] In 2014, Time Out polled several film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors about their top action films;[68] Ronin was 72nd on the list.[69] Paste magazine ranked the film at No. 10 on its "25 Best Movies of 1998".[70]

Video games

Ronin influenced the conception of two action video games: Burnout[lower-alpha 3] and Alpha Protocol.[73]

Footnotes

- ↑ In the DVD commentary, Frankenheimer says four BMWs and five Peugeots were purchased for the chase scene,[10] namely the BMW 535i and Peugeot 406.[28]

- ↑ The briefcase that John Travolta's character opens in Pulp Fiction has also been classified as a MacGuffin.[34]

- ↑ Alex Ward, the creator of Burnout, said the inspiration for the racing game was the DVD version's 15th chapter,[71] which is titled "Crashing the Case," and shows a crash between two opposing cars.[72]

References

- 1 2 "Ronin (1998)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 McCarthy, Todd (September 14, 1998). "Review: 'Ronin'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Ronin (15)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ronin (1998)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "John Frankenheimer: Biography". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 87.

- ↑ Keeling, Robert (April 16, 2018). "Looking back at Ronin". Den of Geek!. United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Magid, Ron (October 1998). "Samurai Tactics". American Cinematographer. p. 1. ISSN 0002-7928. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- Magid, Ron (October 1998). "Samurai Tactics". American Cinematographer. p. 2. ISSN 0002-7928. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- Magid, Ron (October 1998). "Samurai Tactics". American Cinematographer. p. 3. ISSN 0002-7928. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- Magid, Ron (October 1998). "Samurai Tactics". American Cinematographer. p. 4. ISSN 0002-7928. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Travers, Peter (September 25, 1998). "Ronin". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 John Frankenheimer (director). Ronin (audio commentary). MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Sullivan, Michael (September 25, 1998). "Run-of-the-Mill 'Ronin'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 McDonagh, Maitland. "Ronin". TV Guide. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 John Frankenheimer et al. (2004). Ronin: Filming in the Fast Lane (featurette). MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Armstrong 2008, p. 157.

- 1 2 "Ronin: The Casting". Cinema Review. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- 1 2 Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 82.

- 1 2 Bowie, Stephen (November 2006). "Great Directors: John Frankenheimer". Senses of Cinema. ISSN 1443-4059. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Ronin: About the Production". Cinema Review. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Harrison, Eric (August 5, 1998). "Mamet Versus Writers Guild, the Action Thriller Sequel". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- 1 2 Robert Fraisse (director of photography) (2004). Through the Lens (featurette). MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ronin: About The Photography". Cinema Review. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ↑ Robert Fraisse (director of photography) (2017). Close Up: An Interview with Robert Fraisse (featurette). Arrow Video.

- ↑ Crosse 2006, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Jean-Claude Lagniez (car stunt coordinator) (2004). The Driving of Ronin (featurette). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 85.

- ↑ Lane, Anthony (2002). Nobody's Perfect: Writings from The New Yorker (1st ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 249–253. ISBN 978-0-375-71434-4.

- ↑ Kennouche, Sofiane (April 1, 2015). "The greatest drivers' cars to ever feature in movies". Evo. United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Armstrong 2008, p. 159.

- ↑ Armstrong 2008, p. 158.

- ↑ Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 4 Ebert, Roger. "Ronin". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wilmington, Michael (September 25, 1998). "Spy Vs. Spy". Chicago Tribune. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Top 10 Movie MacGuffin". IGN. May 20, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ↑ Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Goldwasser, Dan (November 15, 1998). "A Look at Ronin with Elia Cmiral". Soundtrack.Net. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Plume, Kenneth (July 7, 2000). "Interview with Composer Elia Cmiral". IGN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Elia Cmiral (composer) (2004). Composing the Ronin Score (featurette). MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ronin [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ↑ Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 285.

- 1 2 "Ronin (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- 1 2 Armstrong 2008, p. 160.

- ↑ "Weekly Box Office: September 25 – October 1, 1998". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- 1 2 "Ronin (1998): Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ "1998 Yearly Box Office by MPAA Rating: All R Rated Releases". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- 1 2 "Ronin (1998): Releases". AllMovie. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ Hunt, Bill. "Ronin – DVD review". The Digital Bits. Internet Brands. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ Krauss, David (March 5, 2009). "Ronin Blu-ray review". High-Def Digest. Internet Brands. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ Kauffman, Jeffrey. "Ronin Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Internet Brand. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ↑ Hunt, Bill. "Ronin (Arrow – Blu-ray Review)". The Digital Bits. Internet Brands. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ↑ Spurlin, Thomas (August 29, 2017). "Ronin: Arrow Video Special Edition (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Internet Brands. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Maslin, Janet (September 25, 1998). "Film Review; Real Tough Guys, Real Derring-Do". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- 1 2 Alspector, Lisa. "Ronin". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ↑ Stratton, David (1999). "Ronin Review". SBS. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Pomerance & Palmer 2011, p. 78.

- ↑ "Ronin (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Ronin (1998)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive (CBS Corporation). Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Official website". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

Type the film's title into the 'Find Cinemascore' search box.

- ↑ Howie, Craig (March 27, 2009). "Top 10 movie car chase scenes". CNN. Archived from the original on December 21, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ Cruz, Gilbert (May 1, 2011). "The 15 Greatest Movie Car Chases of All Time". Time. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ↑ Billson, Anne (August 1, 2014). "The 13 best car chases in film". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ↑ Gibron, Bill (April 2, 2015). "The 10 Best Car Chase Films". PopMatters. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ Vejvoda, Jim (September 29, 2016). "Best Car Chases in Movies". IGN. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ↑ Browne, Ben (March 3, 2017). "15 Best Chase Movies Of All Time". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ↑ Guerrasio, Jason (April 4, 2017). "Ranked: The 28 best car chases in movie history". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ "12 Best Car Chases from 'Bullitt' to 'Mad Max: Fury Road'". Collider. June 26, 2017. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ↑ DiGiulio, Matt (January 20, 2016). "12 Best Action Movies You've Never Heard Of". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ↑ "The 100 best action movies". Time Out. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ↑ "The 100 best action movies: 80–71". Time Out. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ↑ "The 25 Best Movies of 1998". Paste. September 22, 2018. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Davison, John (April 26, 2017). "'Burnout' Series Creator Talks Remaking Crash Mode for 'Danger Zone'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ↑ Ronin (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment. May 7, 2013. ASIN 6305263248.

- ↑ Aihoshi, Richard (November 14, 2008). "Alpha Protocol Interview – Part 2". IGN. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Stephen B. (2008). Pictures About Extremes: The Films of John Frankenheimer. United States: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3145-8.

- Crosse, Jesse (2006). The Greatest Movie Car Chases of All Tiime. United States: Motorbooks. ISBN 978-0-7603-2410-3.

- Pomerance, Murray; Palmer, R. Barton, eds. (2011). A Little Solitaire: John Frankenheimer and American Film. United States: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-5059-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ronin (film) |

- Ronin on IMDb

- Ronin at the Internet Movie Firearms Database

- Ronin at the Internet Movie Cars Database