Robert Moog

| Robert Moog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Robert Arthur Moog May 23, 1934 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

August 21, 2005 (aged 71) Asheville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater |

Bronx High School of Science, New York (1952) Queens College, New York (B.S., Physics, 1957) Columbia University (B.S.E.E., 1957) Cornell University (Ph.D., Engineering Physics, 1965) [1] |

| Occupation | Electronic music pioneer, engineer, inventor of Moog synthesizer Entrepreneur |

| Spouse(s) |

Shirleigh Moog (m. 1958; three daughters, one son) Ileana Grams (1996-his death)[1] |

| Relatives |

Laura Moog Lanier (daughter) Matthew Moog (son) Michelle Moog-Koussa (daughter) Renee Moog (daughter) Miranda Richmond (daughter of Ileana Grams) Bill Moog (cousin, founder of Moog Inc.)[1] |

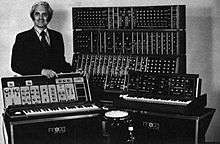

Robert Arthur Moog (/ˈmoʊɡ/ "mogue"; May 23, 1934 – August 21, 2005), founder of Moog Music, was an American engineer and pioneer of electronic music, best known as the inventor of the Moog synthesizer. During his lifetime, Moog founded two companies for manufacturing electronic musical instruments. His innovative electronic design is employed in numerous synthesizers including the Minimoog, Minimoog Voyager, Little Phatty, Moog Taurus, and the Moogerfooger line of effects pedals.

Early life and education

A native of New York City, Moog was raised in Flushing, Queens and attended the Bronx High School of Science, graduating in 1952.[2] He earned a B.S. in physics from Queens College and a B.S. in electrical engineering (likely under a 3-2 engineering program)[3] from Columbia University's School of Engineering and Applied Science in 1957.[4] (Some Columbia sources erroneously maintain that Moog received a master's degree in electrical engineering from the institution in 1956.)[5] He received his Ph.D. in engineering physics from Cornell University in 1965.[6]

Career

R.A. Moog Co. and Moog Music

.png)

In 1953 at age 19, Moog founded his first company, R.A. Moog Co., to manufacture theremin kits. During the 1950s, composer and electronic music pioneer Raymond Scott approached Moog, asking him to design circuits for him. Moog later acknowledged Scott as an important influence. Later, in the 1960s, the company was employed to build modular synthesizers based on Moog's designs. In 1972 Moog changed the company's name to Moog Music. Throughout the 1970s, Moog Music went through various changes of ownership, eventually being bought out by musical instrument manufacturer Norlin. Poor management and marketing led to Moog's departure from his own company in 1977.

In 1978 after leaving his namesake firm, Moog started making electronic musical instruments again with a new company, Big Briar. Their first specialty was theremins, but by 1999 the company expanded to produce a line of analog effects pedals called moogerfoogers. In 1999, Moog partnered with Bomb Factory to co-develop the first digital effects based on Moog technology in the form of plugins for Pro Tools software.

Despite Moog Music's closing in 1993, Moog did not have the rights to market products using his own name throughout the 1990s. Big Briar acquired the rights to use the Moog Music name in 2002 after a legal battle with Don Martin who had previously bought the rights to the name Moog Music. At the same time, Moog designed a new version of the Minimoog called the Minimoog Voyager. The Voyager includes nearly all of the features of the original Model D in addition to numerous modern features.[7]

Development of the Moog synthesizer

The Moog synthesizer was one of the first widely used electronic musical instruments. Early developmental work on the components of the synthesizer occurred at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, now the Computer Music Center. While there, Moog developed the voltage controlled oscillators, ADSR envelope generators, and other synthesizer modules with composer Herbert Deutsch.

Moog created the first voltage-controlled subtractive synthesizer to utilize a keyboard as a controller and demonstrated it at the AES convention in 1964. In 1966, Moog filed a patent application for his unique low-pass filter U.S. Patent 3,475,623, issued in October, 1969. He is a listed inventor on ten US patents.[8][9]

Moog had his theremin company (R. A. Moog Co., which later became Moog Music) manufacture and market his synthesizers. Unlike the few other 1960s synthesizer manufacturers, Moog shipped a piano-style keyboard as the standard user interface. Moog also established standards for analog synthesizer control interfacing, with a logarithmic one volt-per-octave pitch control and a separate pulse triggering signal.

The first Moog instruments were modular synthesizers. In 1971 Moog Music began production of the Minimoog Model D, which was among the first synthesizers that was widely available, portable, and relatively affordable. The first prototype of the minimoog only had about two filters, two envelope generators, and a very small keyboard. Robert Moog knew that this wouldn't be good enough for the average musician, so he kept working on the synthesizer and was able to add more filters, oscillators, and a wider key range.[10]

One of Moog's earliest musical customers was Wendy Carlos, whom he credits with providing feedback valuable to further development. Through his involvement in electronic music, Moog developed close professional relationships with artists such as Don Buchla, Keith Emerson, Rick Wakeman, John Cage, Gershon Kingsley, Clara Rockmore, Jean Jacques Perrey, and Pamelia Kurstin. In a 2000 interview with Salon, Moog said: "I'm a toolmaker. I design things that other people want to use."[11] He has been quoted as saying: "I'm an engineer. I see myself as a toolmaker and the musicians are my customers. They use my tools."[12][13] This quote is widely used and seems to have come from this article's previous misquoting, though this is speculation.

Theremin

Moog constructed his own theremin as early as 1948. Later he described a theremin in the hobbyist magazine Electronics World and offered a kit of parts for the construction of the Electronic World's Theremin, which became very successful. In the late 1980s Moog repaired the original theremin of Clara Rockmore, an accomplishment he considered a high point of his professional career.[14] He also produced, in collaboration with first wife Shirleigh Moog, Mrs. Rockmore's album, The Art of the Theremin.

Moog was a principal interview subject in the award-winning documentary film, Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey, the success of which revived interest in the theremin. Moog wrote the foreword to Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage[15]

Other ventures

He also worked as a consultant and vice president for new product research at Kurzweil Music Systems from 1984–88, helping to develop the Kurzweil K2000.[16] He spent the early 1990s as a research professor of music at the University of North Carolina at Asheville.[17]

Personal life

Moog's first wife was Shirleigh Moog (née Leigh), a grammar school teacher whom he married in 1958. The couple had three daughters (Laura Moog Lanier, Michelle Moog-Koussa, Renee Moog) and one son (Matthew Moog) before their divorce. Moog was married to his second wife Ileana Grams, a philosophy professor, for nine years until his death. Moog's stepdaughter, Miranda Richmond, is Grams's daughter from a previous marriage. Moog also had five grandchildren.

Death

Moog was diagnosed with a glioblastoma multiforme brain tumor on April 28, 2005, and died at the age of 71 in Asheville, North Carolina on August 21, 2005.[18][19]

Legacy

Moog's awards include honorary doctorates from Polytechnic Institute of New York University (New York City), Lycoming College (Williamsport, Pennsylvania), and Berklee College of Music.[20] Moog received a Grammy Trustees Award for lifetime achievement in 1970. In 2002, Moog was honored with a Special Merit/Technical Grammy Award. Moog also received the highly regarded Polar Music Prize in 2001.[21]

In 2009, Albert Glinsky was invited by Moog's widow, Ileana Grams Moog, and his daughter, Michelle Moog-Koussa, to write the authorized biography of Bob Moog.[22] An announcement was made public on the Bob Moog Foundation website on the anniversary of the inventor's birthday.[23] The Bob Moog Foundation was created as a memorial, with the aim of continuing his life's work of developing electronic music. Moog contributed the Foreword to Glinsky's first book, Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage, which has become the standard biography of Leon Theremin.

In 2013, Moog was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.[24]

Archives

On July 18, 2013, Ileana Grams-Moog said she planned to give her late husband's archives, maintained by Bob Moog Foundation, to Cornell University. The foundation offered her $100,000, but Grams-Moog said she would not sell them. She said Cornell could provide better access for researchers, and that the foundation had not made enough progress toward a planned museum to indicate it would be worthy of keeping the collection. The foundation responded that it had sufficiently preserved the collection and made efforts to improve storage, though it could not afford to build the museum yet.[25]

Pronunciation

The surname Moog is often mispronounced. The following interview excerpt reveals Robert Moog's preferred pronunciation:

- — Reviewer: First off: Does your name rhyme with "vogue" or is like a cow's "moo" plus a g at the end?

- — Dr. Robert Moog: It rhymes with "vogue." That is the usual German pronunciation.[26] My father's grandfather came from Marburg, Germany. I like the way that pronunciation sounds better than the way the cow's "moo-g" sounds.[27]

In a deleted scene from the DVD version of the documentary Moog, Moog describes the three pronunciations of the name Moog: the Dutch /moːɣ/, which he believes would be too demanding of English speakers; the preferred Anglo-German pronunciation, /moʊɡ/; and a more anglicized pronunciation, /muːɡ/. Moog reveals that some of his family members prefer the anglicized pronunciation, while others, including himself (and his wife) prefer the Anglo-German pronunciation.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Robert Moog". nndb.com. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ Trangle, Sarina (2012-05-30). "Synthesizer reunion". The Riverdale Press. Archived from the original on 2018-03-03. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

In honor of what would've been Robert Moog's 78th birthday, the Bronx High School of Science started its day with a tribute to the 1952 alumnus who began pioneering the synthesizer in high school.

- ↑ https://undergrad.admissions.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/combined_plan_affiliates_2017-18_v2.pdf

- ↑ https://engineering.columbia.edu/files/engineering/150-stories_0.pdf

- ↑ https://magazine.engineering.columbia.edu/spring-2014/lever-long-enough

- ↑ "Moog Music, Inc". www.referenceforbusiness.com. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ Joe Silva, “Bob Moog: Voyage of Discovery”, Sound On Sound, March 2003 Archived 2008-09-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Moog Patents".

- ↑ "Moog Patents on USPTO database".

- ↑ "Dr Robert & His Modular Moogs". Soundonsound.com. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ↑ "Robert Moog". Salon. 2000-04-25. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ↑ "Robert Moog Quotes". BrainyQuote. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ↑ "Moog Synthesizer Creator Dies | The Cornell Daily Sun". cornellsun.com. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ↑ Glinsky, Albert. Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage Foreword by Robert Moog. University of Illinois Press, 2000, p. xii

- ↑ Glinsky, Albert. Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage, University of Illinois Press, 2000.

- ↑ "Robert Moog biography (1934-2005)". Wired.com. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ↑ "Robert Moog". Obituaries. Variety. 400 (2): 85. 2005-08-29 – via EBSCOhost.

- ↑ Stearns, David Patrick (August 25, 2005). "Obituary: Robert Moog". Theguardian.com. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ↑ Hilton, Bill (July 18, 2013). "Lou Pollack Memorial Park". Findagrave.com. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ Pinch, Trevor (2002). Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer (1 ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 12–16. ISBN 0-674-00889-8.

- ↑ "The Laureates of the Polar Music Prize 2017 are..." Polar Music Prize. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ↑ Pa. professor to write authorized Moog biography, Washington Examiner, 24 May 2012

- ↑ "You searched for albert glinsky - The Bob Moog Foundation". The Bob Moog Foundation. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Moog Inducted into Inventors Hall of Fame". School Band & Orchestra. 16 (5): 10. May 2013. ISSN 1098-3694 – via EBSCOhost.

- ↑ Frankel, Jake (2013-08-12). "Family feud continues over Moog archives". Mountain Xpress. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ↑ The German pronunciation is [moːkʰ]. The English pronunciation [moʊɡ] is an approximation.

- ↑ "The Origins of the Synthesizer: An Interview with Dr. Robert Moog". Members.tripod.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Moog |

- Bob Moog — official website

- The Bob Moog Memorial Foundation for Electronic Music

- Robert Moog discography at Discogs

- Robert Moog on IMDb

- Inventor of the Synthesizer Documentary ~ Moog on YouTube

- Moog Music — official website

- Moog Archives illustrated history of company and products

- MoogFest — festival celebrating Moog

- Moog resources bibliography

- The Moog Taurus Bass Pedals, the Minimoog and the Moog Prodigy

- Pictures of Bob Moog

- Sound samples from the Moog Modular at BlueDistortion.com

- Grave location

Interviews and articles

- Bob Moog RBMA lecture

- Bob Moog Interview at electronicmusic.com

- Article about Bob Moog on SynthMuseum.com

- Interview with Bob Moog on Amazing Sounds

- Article about Robert Moog's career on Salon.com

- Bob Moog: Pioneering Synths Sound on Sound interview from 1998 (archive.org)

- Robert Moog interview in magazine New Scientist

- Radio interview with Moog from 2004 on WNYC (RealAudio) (Moog portion begins 30 minutes into program.)

- Sweetwater Video Interview with Bob Moog discussing his design philosophy and future of synthesis, on Sweetwater.com

- Interview (1993) with Moog about electronic music pioneer Raymond Scott, at RaymondScott.net

- Modulations, a film featuring interviews with Robert Moog on YouTube

- Interview with Robert Moog for the NAMM Oral History Program February 25, 2002

Patents

- Descriptive list of Moog patents by J. Donald Tillman

- U.S. Patent 3,475,623 Electronic High-pass and Low-pass Filters Employing the Base-to-Emitter Resistance of Bipolar Transistors, issued October 1969

- U.S. Patent 4,050,343 Electronic music synthesizer, issued September 1977

- U.S. Patent 4,108,041 Phase shifting sound effects circuit, issued August 1978

- U.S. Patent 4,117,413 Amplifier with multifilter, issued September 1978

- U.S. Patent 4,166,197 Parametric adjustment circuit, issued August 1979

- U.S. Patent 4,180,707 Distortion sound effects circuit, issued December 1979

- U.S. Patent 4,202,238 Compressor-expander for a musical instrument, issued May 1980

- U.S. Patent 4,213,367 Monophonic touch sensitive keyboard, issued July 1980

- U.S. Patent 4,280,387 Frequency following circuit, issued July 1981

- U.S. Patent 4,778,951 Arrays of resistive elements for use in touch panels and for producing electric fields, issued October 1988

Obituaries

- / in BBC News

- in Asheville Citizen-Times

- in Los Angeles Times

- in The New York Times (may require free registration to access)

- in The Economist

- in Mix magazine

- in The Times

Tributes

- Google's tribute to Robert Moog on his 78th birthday in a Google Doodle

- Bob Moog Guestbook at CaringBridge

- Switched On and Ready To Rumble from The New York Times

- A Tribute To Robert Moog — tribute album, entry on Discogs

- We Will Miss You, Bob Moog from BlueDistortion.com

- Tribute Video blog about Robert Moog