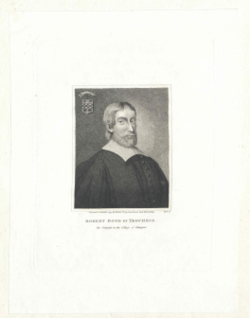

Robert Boyd (university principal)

| The Reverend Robert Boyd | |

|---|---|

Robert Boyd, Principal of the University of Glasgow, 1615-1621 | |

| Church | Church of Scotland |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1604 |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

ca 1578 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died |

January 15, 1627 (aged 48–49) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

Robert Boyd of Trochrig (1578–1627) was a Scottish theological writer, teacher and poet who was Principal of the University of Glasgow from 1615 to 1621 and the University of Edinburgh from 1622 to 1623. He was expelled from these positions due to his opposition to the 1618 Five Articles of Perth and died in Edinburgh on 15 January 1627.

Life

Robert Boyd was the eldest son of Margaret Chalmers and James Boyd, Archbishop of Glasgow and Chancellor of the University of Glasgow from 1572-1581.[1] He was a great-grandson of Robert Boyd, 1st Lord Boyd and connected to the Cassilis family, later the Marquesses of Ailsa.

When Robert was three, his father died and Margaret took him and his brother Thomas to live on an estate in Ayrshire, variously spelled Trochrig, Trochridge, and Trochorege. He studied theology at the University of Edinburgh, where he was taught by the Presbyterian Robert Rollock and graduated in 1594.[2]

In May 1611, Boyd married Ann de Malvera and they had two surviving children, John and Lucretia; after his death in 1627, she married George Sibbald, a long-time friend.[3] She died sometime before 1654.

Career

The Reformation in Scotland created a national Church of Scotland or kirk that was Calvinist in doctrine and Presbyterian in structure. Many Scots studied or taught in French Huguenot universities and in May 1597, Boyd did the same; he spent most of the next three years in Bordeaux and Thouars, until he was offered the position of Professor of Philosophy at the university of Montauban in 1600.[4]

He still wanted to preach and in 1604 became minister for the Reformed Church in Verteuil-sur-Charente; however, his scholastic reputation was such he was persuaded in 1605 to accept a position as Professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Saumur, then Professor of Divinity in 1608.[5] Saumur was the centre of Amyraldism, a distinctive form of Calvinism taught by Moses Amyraut but inspired by John Cameron (1580–1625), a Scot from Glasgow.

This was a period of intense conflict over religion; the 1562-1598 French Wars of Religion caused around three million deaths from war and disease, surpassed only by those of the 1618-1648 Thirty Years' War, one of the most destructive conflicts in recorded history, with an estimated eight million, mostly inhabitants of the Holy Roman Empire.[6] In Britain, similar arguments over religious practices would ultimately lead to the 1638-1652 Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Like most Scots, James VI was a Calvinist but he favoured rule by bishops or Episcopalian governance as a means of control; when he also became King of England in 1603, creating a unified Church of Scotland and England was the first step towards a centralised, Unionist state.[7] However, the Church of England was very different from the kirk in both governance and doctrine and even Scottish bishops viewed many English practices as essentially Catholic.[8]

Despite his father being an Archbishop, Boyd was opposed to any form of Episcopalianism; in 1610, he visited Scotland and in a letter dated 12 July to a colleague in France, wrote that James' decision to establish the Episcopall hierarchy throu all his countreys (sic) would ...force in Popery, Atheisime, ignorance and impiety.[9] Although friends and relatives urged him to return to Scotland, Boyd decided to remain in France but in 1614, James asked him to become Principal at the University of Glasgow and he felt obliged to accept.[10]

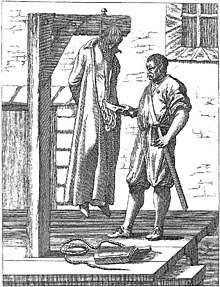

Shortly after his arrival in Glasgow, religious tensions were raised by the public execution on 10 March 1615 of the Jesuit convert, John Ogilvie.[11] Ogilvie's 'fall' was of particular concern since he came from an upper class, Calvinist Scots family and studied at the Protestant University of Helmstedt before his conversion.

His execution fed into the debate over James' proposed reforms or the Five Articles of Perth, which reflected long-standing divisions over the Scottish Reformation. The one that caused the greatest objection was kneeling, which some viewed as idolatry; even those who did not argued Olgivie showed the danger of such 'Popish' practices, even for the educated devout.[12]

In 1618, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland reluctantly approved the Articles but Boyd was one of those who opposed them and they were widely resented.[13] In March 1620, John Fergushill and 48 other ministers were summoned to appear before the Scottish High Commission, an ecclesiastical court of bishops and sympathetic ministers established to enforce the Articles. The accused were found guilty but all denied the authority of the Court to discipline them; Fergushill was a long-standing family connection whom Boyd had mentored since 1604 and he wrote a letter to the Court on his behalf, urging clemency.[14]

This made Boyd an obvious target and in 1621, he was forced to resign from Glasgow University; in October 1622, he was offered the position of Principal at Edinburgh University and Minister at Greyfriars Kirk. [15] Both appointments were blocked by James; Edinburgh was the most important outlet in Scotland for public information and the kirk there was under huge pressure to appoint only ministers willing to conform.[16]

Appointed minister at Paisley in 1626, he fell out with his distant relative Marion Boyd, who had recently become a Catholic and resented his attempts to provide spiritual guidance. Her son Claud broke into Boyd's house, throwing his books and household contents into the street.[17] Shaken by this and suffering from ill-health, Boyd retired once more to Trochrig; he died in January 1627 while visiting Edinburgh.

Works

Boyd's major work was an elaborate 'Commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians', not published until 1652 and described as a theological thesaurus. His Latin poem Hecatombe ad Christum Salvatorem was included by Sir John Scot of Scotstarvet in his Delicias Poetarum Scotorum, reprinted at Edinburgh by Robert Sibbald, nephew of Dr. George Sibbald, who later married his widow Ann.

References

- ↑ "Robert Boyd of Trochrig". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Marshall, Rosalind (2008). "Robert Boyd; 1578-1627". Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3112. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Arraj, Jim, Mullan, David George (2000). Scottish Puritanism, 1590-1638. OUP. pp. 222–223. ISBN 0198269978.

- ↑ Wodrow, Robert (1845). Collections Upon the Lives of the Reformers and Most Eminent Ministers of the Church of Scotland (2012 ed.). Palala Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 1359014446. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ "Robert Boyd of Trochrig". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War (2010 ed.). Penguin. p. 787. ISBN 978-0-14-100614-7.

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 55–58.

- ↑ McDonald, Alan (1998). The Jacobean Kirk, 1567–1625: Sovereignty, Polity and Liturgy. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 185928373X.

- ↑ Wodrow, Robert (1845). Collections Upon the Lives of the Reformers and Most Eminent Ministers of the Church of Scotland (2012 ed.). Palala Press. p. 84. ISBN 1359014446. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Marshall, Rosalind (2008). "Robert Boyd; 1578-1627". Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3112. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Lamal, Nina. "Hanged & Drawn: How the story of a Scottish martyr spread across Germany". Preserving the World's Rarest Books. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Houlbrooke, Ralph (ed), Stewart, Laura (author) (2006). Propaganda, Public Opinion and the Perth Articles Debate in James VI and I: Ideas, Authority, and Government. Routledge. pp. 158–160. ISBN 0754654109. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Mitchison, Rosalind (2002). A History of Scotland. Routledge. pp. 166–168. ISBN 0415278805.

- ↑ Houlbrooke, Ralph (ed), Stewart, Laura (author) (2006). Propaganda, Public Opinion and the Perth Articles Debate in James VI and I: Ideas, Authority, and Government. Routledge. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0754654109. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "Robert Boyd (1578-1627)". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Houlbrooke, Ralph (ed), Stewart, Laura (author) (2006). Propaganda, Public Opinion and the Perth Articles Debate in James VI and I: Ideas, Authority, and Government. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 0754654109. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Marshall, Rosalind (2008). "Robert Boyd; 1578-1627". Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3112. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

External links

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Patrick Sands |

Principal of the University of Edinburgh 1622–1623 |

Succeeded by John Adamson |