Intel Management Engine

The Intel Management Engine (ME), also known as the Manageability Engine,[1][2] is an autonomous subsystem that has been incorporated in virtually all of Intel's processor chipsets since 2008.[3][4][1] The subsystem primarily consists of proprietary firmware running on a separate microprocessor that performs tasks during boot-up, while the computer is running, and while it is asleep.[5] As long as the chipset or SoC is connected to current (via battery or power supply), it continues to run even when the system is turned off.[6] Intel claims the ME is required to provide full performance.[7] Its exact workings[8] are largely undocumented[9] and its code is obfuscated using confidential huffman tables stored directly in hardware, so the firmware does not contain the information necessary to decode its contents.[10] Intel's main competitor AMD has incorporated the equivalent AMD Secure Technology (formally called Platform Security Processor) in virtually all of its post-2013 CPUs.[11]

The Management Engine is often confused with Intel AMT. AMT runs on the ME, but is only available on processors with vPro. AMT enables owners remote administration of their computer,[12] like turning it on or off and reinstalling the operating system. However, the ME itself is built into all Intel chipsets since 2008, not only those with AMT. While AMT can be unprovisioned by the owner, there is no official, documented way to disable the ME.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and security expert Damien Zammit accuse the ME of being a backdoor and a privacy concern.[13][4] Zammit states that the ME has full access to memory (without the parent CPU having any knowledge); has full access to the TCP/IP stack and can send and receive network packets independent of the operating system, thus bypassing its firewall.[12] Intel asserts that it "does not put back doors in its products" and that its products do not "give Intel control or access to computing systems without the explicit permission of the end user."[12][14]

Several weaknesses have been found in the ME. On May 1, 2017, Intel confirmed a Remote Elevation of Privilege bug (SA-00075) in its Management Technology.[15] Every Intel platform with provisioned Intel Standard Manageability, Active Management Technology, or Small Business Technology, from Nehalem in 2008 to Kaby Lake in 2017 has a remotely exploitable security hole in the ME.[16][17] Several ways to disable the ME without authorization that could allow ME's functions to be sabotaged have been found.[18][19][20] Additional major security flaws in the ME affecting a very large number of computers incorporating ME, Trusted Execution Engine (TXE), and Server Platform Services (SPS) firmware, from Skylake in 2015 to Coffee Lake in 2017, were confirmed by Intel on 20 November 2017 (SA-00086).[21] Unlike SA-00075, this bug is even present if AMT is absent, not provisioned or if the ME was "disabled" by any of the known unofficial methods.[22] In July 2018 another set of vulnerabilitites were disclosed (SA-00112).[23] In September 2018, yet another vulnerability was published (SA-00125).[24]

Design

Hardware

Starting with ME 11, it is based on the Intel Quark x86-based 32-bit CPU and runs the MINIX 3 operating system.[25] The ME state is stored in a partition of the SPI flash, using the Embedded Flash File System (EFFS).[26] Previous versions were based on an ARC core, with the Management Engine running the ThreadX RTOS from Express Logic. Versions 1.x to 5.x of the ME used the ARCTangent-A4 (32-bit only instructions) whereas versions 6.x to 8.x used the newer ARCompact (mixed 32- and 16-bit instruction set architecture). Starting with ME 7.1, the ARC processor could also execute signed Java applets.

The ME has its own MAC and IP address for the out-of-band interface, with direct access to the Ethernet controller; one portion of the Ethernet traffic is diverted to the ME even before reaching the host's operating system, for what support exists in various Ethernet controllers, exported and made configurable via Management Component Transport Protocol (MCTP).[27][28] The ME also communicates with the host via PCI interface.[26] Under Linux, communication between the host and the ME is done via /dev/mei.[29]

Until the release of Nehalem processors, the ME was usually embedded into the motherboard's northbridge, following the Memory Controller Hub (MCH) layout.[30] With the newer Intel architectures (Intel 5 Series onwards), ME is included into the Platform Controller Hub (PCH).[31][32]

Firmware

By Intel's current terminology as of 2017, ME is one of several firmware sets for the Converged Security and Manageability Engine (CSME). Prior to AMT version 11, CSME was called Intel Management Engine BIOS Extension (Intel MEBx).[1]

- Management Engine (ME) – mainstream chipsets[33]

- Server Platform Services (SPS) – server chipsets and SoCs[34][33][35]

- Trusted Execution Engine (TXE) – tablet/embedded/low power[36][37]

The Russian company Positive Technologies (Dmitry Sklyarov) found that the ME firmware version 11 runs MINIX 3.[38][39][40]

Modules

- Active Management Technology (AMT)[2]

- Alert Standard Format (ASF) support

- Intel Boot Guard (IBG)[41] and Secure Boot[37]

- Integrated Clock Controller (ICC)

- Quiet System Technology (QST), formerly known as Advanced Fan Speed Control (AFSC), which provides support for acoustically-optimized fan speed control, and monitoring of temperature, voltage, current and fan speed sensors that are provided in the chipset, CPU and other devices present on the motherboard. Communication with the QST firmware subsystem is documented and available through the official software development kit (SDK).[42]

- Protected Audio Video Path (used in PlayReady DRM)

- Intel Security Assist (ISA)

- Serial over LAN (SOL)[43]

- Firmware-based Trusted Platform Module (TPM)[41]

Security vulnerabilities

Disabling the ME

It is normally not possible for the user to disable the ME. Potentially risky, undocumented methods to do so were discovered, however.[21] These methods are not supported by Intel. The ME's security architecture is supposed to prevent disabling, and thus its possibility is considered a security vulnerability. For example, a virus could abuse it to make the computer lose some of the functionality that the typical end-user expects, such as the ability to play media with DRM. Yet, critics consider the weaknesses not as bugs, but as features.

Strictly speaking, none of the known methods disables the ME completely, since it is required for booting the main CPU. All known methods merely make the ME go into abnormal states soon after boot, in which it seems not to have any working functionality. The ME is still physically connected to the current and its microprocessor is continuing to execute code.

Undocumented methods

Firmware neutering

In 2016, the me_cleaner project found that the ME's integrity verification is broken. The ME is supposed to detect that it has been tampered with, and, if this is the case, shut down the PC forcibly after 30 minutes.[44] This prevents a compromised system from running undetected, yet allows the owner to fix the issue by flashing a valid version of the ME firmware during the grace period. As the project found out, by making unauthorized changes to the ME firmware, it was possible to force it into an abnormal error state that prevented triggering the shutdown even if large parts of the firmware had been overwritten and thus made inoperable.

"High Assurance Platform" mode

In August 2017, Russian company Positive Technologies (Dmitry Sklyarov) published a method to disable the ME via an undocumented built-in mode. As Intel has confirmed[45] the ME contains a switch to enable government authorities such as the NSA to make the ME go into High-Assurance Platform (HAP) mode after boot. This mode disables all of ME's functions. It is authorized for use by government authorities only and is supposed to be available only in machines produced for them. Yet it turned out that most machines sold on the retail market can be tricked into activating the switch.[46][47]. Manipulation of the HAP bit was quickly incorporated into the me_cleaner project[48].

Commercial ME disablement

In late 2017, several laptop vendors announced their intentions to ship laptops with the Intel ME disabled:

- Purism previously petitioned Intel to sell processors without the ME, or release its source code, calling it "a threat to users' digital rights"[49]. In March 2017, Purism announced[50] that it had neutralized the ME by erasing the majority of the ME code from the flash memory. It further announced in October 2017[51] that new batches of their Debian-based Librem line of laptops will ship with the ME neutralized (via erasing the majority of ME code from the flash, as previously announced), and additionally disabling most ME operation via the HAP bit. Updates for existing Librem laptops were also announced.

- System 76 announced in November 2017[52] their plan to disable the ME on their new and recent Ubuntu-based machines via the HAP bit.

- Dell, in December 2017,[53] began showing certain laptops on its website that offered the "Systems Management" option "Intel vPro - ME Inoperable, Custom Order" for an additional fee. Dell has not announced or publicly explained the methods used. In response to press requests, Dell stated that those systems had been offered for quite a while, but not for the general public, and had found their way to the website only inadvertently.[54] The laptops are available only by custom order and only to military, government and intelligence agencies.[55] They are specifically designed for covert operations, such as providing a very robust case and a "stealth" operating mode kill switch that disables display, LED lights, speaker, fan and any wireless technology[56].

Effectiveness against vulnerabilities

None of the two methods to disable the ME discovered so far turned out to be an effective countermeasure against the SA-00086 vulnerability.[57] This is because the vulnerability is in an early-loaded ME module that is essential to boot the main CPU.[58]

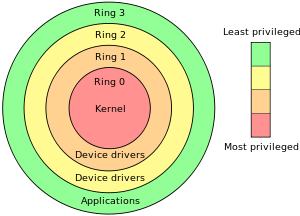

Ring −3 rootkit

A ring −3 rootkit was demonstrated by Invisible Things Lab for the Q35 chipset; it does not work for the later Q45 chipset as Intel implemented additional protections.[59] The exploit worked by remapping the normally protected memory region (top 16 MB of RAM) reserved for the ME. The ME rootkit could be installed regardless of whether the AMT is present or enabled on the system, as the chipset always contains the ARC ME coprocessor. (The "−3" designation was chosen because the ME coprocessor works even when the system is in the S3 state, thus it was considered a layer below the System Management Mode rootkits.[30]) For the vulnerable Q35 chipset, a keystroke logger ME-based rootkit was demonstrated by Patrick Stewin.[60][61]

Zero-touch provisioning

Another security evaluation by Vassilios Ververis showed serious weaknesses in the GM45 chipset implementation. In particular, it criticized AMT for transmitting unencrypted passwords in the SMB provisioning mode when the IDE redirection and Serial over LAN features are used. It also found that the "zero touch" provisioning mode (ZTC) is still enabled even when the AMT appears to be disabled in BIOS. For about 60 euros, Ververis purchased from Go Daddy a certificate that is accepted by the ME firmware and allows remote "zero touch" provisioning of (possibly unsuspecting) machines, which broadcast their HELLO packets to would-be configuration servers.[62]

SA-00075 (aka Silent Bob is Silent)

In May 2017, Intel confirmed that many computers with AMT have had an unpatched critical privilege escalation vulnerability (CVE-2017-5689).[17][63][15][64][65] The vulnerability, which was nicknamed "Silent Bob is Silent" by the researchers who had reported it to Intel,[66] affects numerous laptops, desktops and servers sold by Dell, Fujitsu, Hewlett-Packard (later Hewlett Packard Enterprise and HP Inc.), Intel, Lenovo, and possibly others.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] Those researchers claimed that the bug affects systems made in 2010 or later.[73] Other reports claimed the bug also affects systems made as long ago as 2008.[74][17] The vulnerability was described as giving remote attackers:

"full control of affected machines, including the ability to read and modify everything. It can be used to install persistent malware (possibly in firmware), and read and modify any data."

— Tatu Ylönen, ssh.com[66]

PLATINUM

In June 2017, the PLATINUM cybercrime group became notable for exploiting the serial over LAN (SOL) capabilities of AMT to perform data exfiltration of stolen documents.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82]

SA-00086

Some months after the previous bugs, and subsequent warnings from the EFF,[4] security firm Positive Technologies claimed to have developed a working exploit.[83] On 20 November, 2017 Intel confirmed that a number of serious flaws had been found in the Management Engine (mainstream), Trusted Execution Engine (tablet/mobile), and Server Platform Services (high end server) firmware, and released a "critical firmware update".[84][85] Essentially every Intel-based computer for the last several years, including most desktops and servers, were found to be vulnerable to having their security compromised, although all the potential routes of exploitation were not entirely known.[85] It is not possible to patch the problems from the operating system, and a firmware (UEFI, BIOS) update to the motherboard is required, which was anticipated to take quite some time for the many individual manufacturers to accomplish, if it ever would be for many systems.[21]

Affected systems[84]

- Intel Atom – C3000 family

- Intel Atom – Apollo Lake E3900 series

- Intel Celeron – N and J series

- Intel Core (i3, i5, i7, i9) – 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th generation

- Intel Pentium – Apollo Lake

- Intel Xeon – E3-1200 v5 and v6 product family

- Intel Xeon – Scalable family

- Intel Xeon – W family

Mitigation

None of the known unofficial methods to disable the ME prevent exploitation of the vulnerability. A firmware update by the vendor is required. However, those who discovered the vulnerability note that firmware updates are not fully effective either, as an attacker with access to the ME firmware region can simply flash an old, vulnerable version and then exploit the bug.[86]

SA-00112

In July 2018 Intel announced that 3 vulnerabilities (CVE-2018-3628, CVE-2018-3629 and CVE-2018-3632) had been discovered and that a patch for the CSME firmware would be required. Intel indicated there would be no patch for 3rd generation Core processors or earlier despite chips or their chipsets as far back as Intel Core 2 Duo vPro and Intel Centrino 2 vPro being affected.[23]

Claims that ME is a backdoor

Critics like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and security expert Damien Zammit accused the ME of being a backdoor and a privacy concern.[13][4] Zammit stresses that the ME has full access to memory (without the parent CPU having any knowledge); has full access to the TCP/IP stack and can send and receive network packets independently of the operating system, thus bypassing its firewall.[12]

Intel responded by saying that "Intel does not put back doors in its products nor do our products give Intel control or access to computing systems without the explicit permission of the end user."[12] and "Intel does not and will not design backdoors for access into its products. Recent reports claiming otherwise are misinformed and blatantly false. Intel does not participate in any efforts to decrease security of its technology."[14]

In the context of criticism of the Intel ME and AMD Secure Technology it has been pointed out that the NSA budget request for 2013 contained a Sigint Enabling Project with the goal to "Insert vulnerabilities into commercial encryption systems, IT systems, …" and it has been conjectured that Intel ME and AMD Secure Technology might be part of that programme.[87]

Reactions

As of 2017, Google was attempting to eliminate proprietary firmware from its servers and found that the ME was a hurdle to that.[21]

Reaction by AMD processor vendors

Shortly after SA-00086 was patched, vendors for AMD processor mainboards started shipping BIOS updates that allow disabling the AMD Secure Technology,[88] a subsystem with similar function as the ME.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Getting Started with Intel® Active Management Technology (AMT)". Intel.

- 1 2 "Intel® AMT and the Intel® ME". Intel.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions for the Intel® Management Engine Verification Utility".

Built into many Intel® Chipset–based platforms is a small, low-power computer subsystem called the Intel® Management Engine (Intel® ME).

- 1 2 3 4 Portnoy, Erica; Eckersley, Peter (May 8, 2017). "Intel's Management Engine is a security hazard, and users need a way to disable it".

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions for the Intel® Management Engine Verification Utility".

The Intel® ME performs various tasks while the system is in sleep, during the boot process, and when your system is running.

- ↑ https://www.blackhat.com/eu-17/briefings/schedule/#how-to-hack-a-turned-off-computer-or-running-unsigned-code-in-intel-management-engine-8668

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions for the Intel® Management Engine Verification Utility".

This subsystem must function correctly to get the most performance and capability from your PC.

- ↑ https://www.howtogeek.com/334013/intel-management-engine-explained-the-tiny-computer-inside-your-cpu/

- ↑ https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2017/05/intels-management-engine-security-hazard-and-users-need-way-disable-it

- ↑ http://io.netgarage.org/me/

- ↑ https://libreboot.org/faq.html#amd

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wallen, Jack (July 1, 2016). "Is the Intel Management Engine a backdoor?".

- 1 2 "Intel x86 CPUs Come with a Secret Backdoor That Nobody Can Touch or Disable".

- 1 2 https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/08/29/intel_management_engine_can_be_disabled/

- 1 2 "Intel® Product Security Center". Security-center.intel.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Charlie Demerjian (2017-05-01). "Remote security exploit in all 2008+ Intel platforms". SemiAccurate. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- 1 2 3 "Red alert! Intel patches remote execution hole that's been hidden in chips since 2010". Theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Alaoui, Youness (October 19, 2017). "Deep dive into Intel Management Engine disablement".

- ↑ Alaoui, Youness (March 9, 2017). "Neutralizing the Intel Management Engine on Librem Laptops".

- ↑ "Positive Technologies Blog: Disabling Intel ME 11 via undocumented mode". Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "Intel Patches Major Flaws in the Intel Management Engine". Extreme Tech.

- ↑ https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/12/06/intel_management_engine_pwned_by_buffer_overflow/

- 1 2 https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/security-center/advisory/intel-sa-00112.html

- ↑ https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/security-center/advisory/intel-sa-00125.html

- ↑ "Positive Technologies Blog: Disabling Intel ME 11 via undocumented mode". Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- 1 2 Igor Skochinsky (Hex-Rays) Rootkit in your laptop, Ruxcon Breakpoint 2012

- ↑ "Intel Ethernet Controller I210 Datasheet" (PDF). Intel. 2013. pp. 1, 15, 52, 621&ndash, 776. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ "Intel Ethernet Controller X540 Product Brief" (PDF). Intel. 2012. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- 1 2 Joanna Rutkowska. "A Quest to the Core" (PDF). Invisiblethingslab.com. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Platforms II" (PDF). Users.nik.uni-obuda.hu. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- 1 2 "FatTwin® F618R3-FT+ F618R3-FTPT+ User's Manual" (PDF). Super Micro.

The Manageability Engine, which is an ARC controller embedded in the IOH (I/O Hub), provides Server Platform Services (SPS) to your system. The services provided by SPS are different from those provided by the ME on client platforms.

- ↑ "Intel® Xeon® Processor E3-1200 v6 Product Family Product Brief". Intel.

Intel® Server Platform Services (Intel® SPS): Designed for managing rack-mount servers, Intel® Server Platform Services provides a suite of tools to control and monitor power, thermal, and resource utilization.

- ↑ "Intel® Xeon® Processor D-1500 Product Family" (PDF). Intel.

- ↑ "Intel Trusted Execution Engine Driver". Dell.

This package provides the drivers for the Intel Trusted Execution Engine and is supported on Dell Venue 11 Pro 5130 Tablet

- 1 2 "Intel® Trusted Execution Engine Driver for Intel® NUC Kit NUC5CPYH, NUC5PPYH, NUC5PGYH". Intel.

Installs the Intel® Trusted Execution Engine (Intel® TXE) driver and firmware for Windows® 10 and Windows 7*/8.1*, 64-bit. The Intel TXE driver is required for Secure Boot and platform security features.

- ↑ "Positive Technologies Blog: Disabling Intel ME 11 via undocumented mode". Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ↑ Intel ME: The Way of the Static Analysis, Troopers 2017

- ↑ Positive Technologies Blog:The Way of the Static Analysis

- 1 2 "Intel Hardware-based Security Technologies for Intelligent Retail Devices" (PDF). Intel.

- ↑ "Intel Quiet System Technology 2.0: Programmer's Reference Manual" (PDF). Intel. February 2010. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ "Using Intel® AMT serial-over-LAN to the fullest". Intel.

- ↑ https://github.com/corna/me_cleaner

- ↑ https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/hardware/researchers-find-a-way-to-disable-much-hated-intel-me-component-courtesy-of-the-nsa/

- ↑ http://blog.ptsecurity.com/2017/08/disabling-intel-me.html

- ↑ https://github.com/corna/me_cleaner/wiki/HAP-AltMeDisable-bit

- ↑ https://github.com/corna/me_cleaner/commit/ced3b46ba2ccd74602b892f9594763ef34671652

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20160616070449/https://puri.sm/posts/petition-for-intel-to-release-an-me-less-cpu-design/

- ↑ Alaoui, Youness (2017-03-09). "Neutralizing the Intel Management Engine on Librem Laptops". puri.sm. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ↑ https://puri.sm/posts/purism-librem-laptops-completely-disable-intel-management-engine/

- ↑ http://blog.system76.com/post/168050597573/system76-me-firmware-updates-plan

- ↑ https://liliputing.com/2017/12/dell-also-sells-laptops-intel-management-engine-disabled.html

- ↑ https://www.extremetech.com/computing/260219-dell-sells-pcs-without-intel-management-engine-tradeoffs

- ↑ https://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Dell-schaltet-Intel-Management-Engine-in-Spezial-Notebooks-ab-3909860.html

- ↑ http://www.dell.com/support/manuals/us/en/04/latitude-14-5414-laptop/5414_om/stealth-mode?guid=guid-3655713b-6a1b-46a8-ba69-eaa3c324b3cd&lang=en-us

- ↑ https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/12/06/intel_management_engine_pwned_by_buffer_overflow/

- ↑ https://twitter.com/rootkovska/status/938458875522666497

- ↑ "Invisible Things Lab to present two new technical presentations disclosing system-level vulnerabilities affecting modern PC hardware at its core" (PDF). Invisiblethingslab.com. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "Berlin Institute of Technology : FG Security in telecommunications : Evaluating "Ring-3" Rootkits" (PDF). Stewin.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "Persistent, Stealthy Remote-controlled Dedicated Hardware Malware" (PDF). Stewin.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "Security Evaluation of Intel's Active Management Technology" (PDF). Web.it.kth.se. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "CVE - CVE-2017-5689". Cve.mitre.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Intel Hidden Management Engine - x86 Security Risk?". Darknet. 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Garrett, Matthew (2017-05-01). "Intel's remote AMT vulnerablity". mjg59.dreamwidth.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- 1 2 3 "2017-05-05 ALERT! Intel AMT EXPLOIT OUT! IT'S BAD! DISABLE AMT NOW!". Ssh.com\Accessdate=2017-05-07.

- ↑ Dan Goodin (2017-05-06). "The hijacking flaw that lurked in Intel chips is worse than anyone thought". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ↑ "General: BIOS updates due to Intel AMT IME vulnerability - General Hardware - Laptop - Dell Community". En.community.dell.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Advisory note: Intel Firmware vulnerability – Fujitsu Technical Support pages from Fujitsu Fujitsu Continental Europe, Middle East, Africa & India". Support.ts.fujitsu.com. 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ↑ "HPE | HPE CS700 2.0 for VMware". H22208.www2.hpe.com. 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Intel® Security Advisory regarding escalation o... |Intel Communities". Communities.intel.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Intel Active Management Technology, Intel Small Business Technology, and Intel Standard Manageability Remote Privilege Escalation". Support.lenovo.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "MythBusters: CVE-2017-5689". Embedi.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Charlie Demerjian (2017-05-01). "Remote security exploit in all 2008+ Intel platforms". SemiAccurate.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Sneaky hackers use Intel management tools to bypass Windows firewall". Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ Tung, Liam. "Windows firewall dodged by 'hot-patching' spies using Intel AMT, says Microsoft - ZDNet". Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ "PLATINUM continues to evolve, find ways to maintain invisibility". Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ "Malware Uses Obscure Intel CPU Feature to Steal Data and Avoid Firewalls". Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ "Hackers abuse low-level management feature for invisible backdoor". iTnews. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ "Vxers exploit Intel's Active Management for malware-over-LAN • The Register". www.theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ Security, heise. "Intel-Fernwartung AMT bei Angriffen auf PCs genutzt". Security. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ "PLATINUM activity group file-transfer method using Intel AMT SOL". Channel 9. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ How to Hack a Turned-Off Computer, or Running Unsigned Code in Intel Management Engine Black Hat Europe 2017

- 1 2 "Intel® Management Engine Critical Firmware Update (Intel SA-00086)". Intel.

- 1 2 "Intel Chip Flaws Leave Millions of Devices Exposed". Wired.

- ↑ https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/12/06/intel_management_engine_pwned_by_buffer_overflow/

- ↑ https://www.heise.de/ct/ausgabe/2018-7-Briefe-E-Mail-Hotline-3992838.html#p_41

- ↑ https://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/AMD-Secure-Processor-PSP-wohl-bei-einigen-Ryzen-Mainboards-abschaltbar-3913635.html