Richard Barthelmess

| Richard Barthelmess | |

|---|---|

|

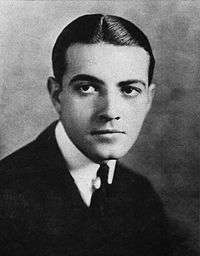

Publicity photo of Barthelmess for A Modern Hero (1934) | |

| Born |

May 9, 1895 New York City, U.S. |

| Died |

August 17, 1963 (aged 68) Southampton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery |

| Education | Hudson River Military Academy |

| Alma mater | Trinity College |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1916–1942 |

| Spouse(s) |

Jessica Stewart Sargent (m. 1928–1963) |

| Children | 2 |

Richard Semler Barthelmess (May 9, 1895 – August 17, 1963) was an American film actor, principally of the Hollywood silent era. He starred opposite Lillian Gish in D.W. Griffith's Broken Blossoms (1919) and Way Down East (1920) and was among the founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1927. The following year, he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor for two films: The Patent Leather Kid and The Noose.[1]

Early life

Barthelmess was born in New York City, the son of Caroline W. Harris, a stage actress,[2][3] and Alfred W. Barthelmess.[4] His father died when he was a year old.[5] Through his mother, he grew up in the theatre, doing "walk-ons" from an early age. In contrast to that, he was educated at Hudson River Military Academy at Nyack and Trinity College at Hartford, Connecticut.[6] He did some acting in college and other amateur productions. By 1919 he had five years in stock company experience.[7]

Career

Russian actress Alla Nazimova, a friend of the family, was taught English by Caroline Barthelmess.[8] Nazimova convinced Richard Barthelmess to try acting professionally, and he made his debut screen appearance in 1916 in the serial Gloria's Romance as an uncredited extra. He also appeared as a supporting player in several films starring Marguerite Clark.

His next role, in War Brides opposite Nazimova, attracted the attention of director D.W. Griffith, who offered him several important roles, finally casting him opposite Lillian Gish in Broken Blossoms (1919) and Way Down East (1920). He founded his own production company, Inspiration Film Company, together with Charles Duell and Henry King. One of their films, Tol'able David (1921), in which Barthelmess starred as a teenage mailman who finds courage, was a major success. In 1922, Photoplay described him as the "idol of every girl in America."[9]

Barthelmess had a large female following during the 1920s. An admirer wrote to the editor of Picture-Play Magazine in 1921:

Different fans have different opinions, and although Wallace Reid, Thomas Meighan, and Niles Welch are mighty fine chaps, I think that Richard Barthelmess beats them all. Dick is getting more and more popular every day, and why? Because his wonderful black hair and soulful eyes are enough to make any young girl adore him. The first play I saw Dick in was Boots—Dorothy Gish playing the lead. This play impressed me so that I went to see every play in which he appeared—Three Men and a Girl, Scarlet Days, The Love Flower, and Broken Blossoms, in which I decided that Dick was my favorite. I am looking forward to Way Down East as being a great success, because I know Dick will play a good part.[10]

Barthelmess soon became one of Hollywood's highest paid performers, starring in such classics as The Patent Leather Kid in 1927 and The Noose in 1928; he was nominated for Best Actor at the first Academy Awards for his performance in both films. In addition, he won a special citation for producing The Patent Leather Kid.

With the advent of the sound era, Barthelmess' fortunes changed. He made several talkie films, most notably Son of the Gods (1930), The Dawn Patrol (1930), The Last Flight (1931), and The Cabin in the Cotton (1932), Central Airport (1933), and a supporting role as a disgraced pilot and Rita Hayworth's character's husband in Only Angels Have Wings (1939).

Post-acting career

Barthelmess failed to maintain the stardom of his silent film days and gradually left entertainment. He enlisted in the United States Navy Reserve during World War II, and served as a lieutenant commander. He never returned to film, preferring instead to live off his investments.

Personal life

Marriages and family

On June 18, 1920, Barthelmess married Mary Hay, a stage and screen star, in New York.[2] They had one daughter, Mary Barthelmess, before divorcing.[11]

In 1927, Barthelmess became engaged to Katherine Young Wilson, a Broadway actress.[12][13] However, the engagement was called off, possibly due to his affair about this time with the journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns.[14]

In 1928, Barthelmess married Jessica Stewart Sargent.[2] He would later adopt her son Stewart from a previous marriage. They remained married until Barthelmess’ death in 1963.

Death

Barthelmess died of throat cancer on August 17, 1963, aged 68, in Southampton, New York.[2] He was interred at the Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum in Hartsdale, New York.

Legacy

- Barthelmess was a founder of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.[15]

- In 1960, Barthelmess received a motion picture star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6755 Hollywood Boulevard for his contributions to the film industry.[16]

- Barthelmess was among the second group of recipients of the George Eastman Award in 1957, given by the George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.[17]

- Composer Katherine Allan Lively dedicated her piano composition Within the Walls of China: A Chinese Episode to Barthelmess in the sheet music published in 1923 by G. Schirmer, Inc.[18] An article in The Music Trades reported that Mrs. Lively was inspired by a viewing of the film Broken Blossoms, and performed the piece for Barthelmess and his friends in New York in the summer of 1922.[19]

Filmography

- Features

- Gloria's Romance (1916)

- War Brides (1916)

- Snow White (1916)

- Just a Song at Twilight (1916)

- The Moral Code (1917)

- The Eternal Sin (1917)

- The Valentine Girl (1917)

- The Soul of a Magdalen (1917)

- The Streets of Illusion (1917)

- Camille (1917)

- Bab's Diary (1917)

- Bab's Burglar (1917)

- Nearly Married (1917)

- For Valour (1917)

- The Seven Swans (1917)

- Sunshine Nan (1918)

- Rich Man, Poor Man (1918)

- Hit-The-Trail Holliday (1918)

- Wild Primrose (1918)

- The Hope Chest (1918)

- Boots (1918)

- The Girl Who Stayed at Home (1919)

- Three Men and a Girl (1919)

- Peppy Polly (1919)

- Broken Blossoms (1919)

- I'll Get Him Yet (1919)

- Scarlet Days (1919)

- The Idol Dancer (1920)

- The Love Flower (1920)

- Way Down East (1920)

- Experience (1921)

- Tol'able David (1921)

- The Seventh Day (1922)

- Sonny (1922)

- The Bond Boy (1922)

- Fury (1923)

- The Bright Shawl (1923)

- The Fighting Blade (1923)

- Twenty-One (1923)

- The Enchanted Cottage (1924)

- Classmates (1924)

- New Toys (1925)

- Soul-Fire (1925)

- Shore Leave (1925)

- The Beautiful City (1925)

- Just Suppose (1926)

- Ranson's Folly (1926)

- The Amateur Gentleman (1926)

- The White Black Sheep (1926)

- The Patent Leather Kid (1927)

- The Drop Kick (1927)

- The Noose (1928)

- The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come (1928)

- Wheel of Chance (1928)

- Out of the Ruins (1928)

- Scarlet Seas (1928)

- Weary River (1929)

- Drag (1929)

- Young Nowheres (1929)

- The Show of Shows (1929)

- Son of the Gods (1930)

- The Dawn Patrol (1930)

- The Lash (1930)

- The Finger Points (1931)

- The Last Flight (1931)

- Alias the Doctor (1932)

- The Cabin in the Cotton (1932)

- Central Airport (1933)

- Heroes for Sale (1933)

- Massacre (1934)

- A Modern Hero (1934)

- Midnight Alibi (1934)

- Four Hours to Kill! (1935)

- Spy of Napoleon (1936)

- Only Angels Have Wings (1939)

- The Man Who Talked Too Much (1940)

- The Spoilers (1942)

- The Mayor of 44th Street (1942)

- Short subjects

- Camille (1926) (home movie by cariacaturist Ralph Barton)

- The Stolen Jools (1931)

- How I Play Golf, by Bobby Jones No. 1: The Putter (1931)

- Starlit Days at the Lido (1935)

- Meet the Stars #5: Hollywood Meets the Navy (1941)

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ "("Barthlemess" search results)". Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Donnelley, Paul (2003). Fade to Black: A Book of Movie Obituaries. Music Sales Group. pp. 70&ndash, 71. ISBN 9780711995123. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ↑ IBDb profile of Caroline Harris; Deaths Last Night, Ironwood Daily Globe (Ironwood, Michigan) April 24, 1937, p. 11, c. 2.

- ↑ Census Place: Manhattan, New York, New York; Roll: 1103; Page: 4A; Enumeration District: 0470; FHL microfilm: 1241103

- ↑ "Tea With Mrs. Barthelmess – An Intimate Chat With the Mother of Dick", The Home Movie Journal, June 1926

- ↑ Pawlak, Debra Ann (2012). Bringing Up Oscar: The Story of the Men and Women Who Founded the Academy. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781605982168. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ↑ The Motion Picture Studio Directory, 1919; Page: 48. The 1900 US Census reported his mother ran a boardinghouse as housekeeper with a maid and butler. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 583830 / MLR Number A1 534; NARA Series: M1490; Roll #: 1009.

- ↑ A Pictorial History of the Silent Screen by Daniel Blum, ca. 1953, p. 111.

- ↑ "The Shadow Stage". Photoplay. New York: Photoplay Publishing Company. February 1922. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ↑ G. C. (1921). "What the Fans Think" Picture-Play Magazine

- ↑ Profile at IBDb

- ↑ Katherine Wilson's profile at IBDb

- ↑ Barthelmess and Wilson's wedding announcement in The Reading Eagle, August 24, 1927 (accessed 5 December 2011)

- ↑ Scott Eyman, The Speed of Sound,1999, p. 305.

- ↑ "History of the Academy: Original 36 founders of the Academy Actors". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences website. 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved January 19, 2017

- ↑ "George Eastman Award" (archive). eastmanhouse.org. George Eastman House. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Published sheet music on-line at Maine Music Box". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ↑ (1922) The Music Trades, 64 (21 October), 40.

- Bibliography

- Hammond, Michael. War Relic and Forgotten Man: Richard Barthelmess as Celluloid Veteran in Hollywood 1922–1933, Journal of War & Culture Studies, 6:4, 2013, p. 282-301. http://www.maneyonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/1752628013Y.0000000005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Barthelmess. |