Reported kidnapping of Aimee Semple McPherson

| Aimee Semple McPherson | |

|---|---|

Prior to her 1926 reported kidnapping, Aimee Semple McPherson was little known outside of Southern California. After she fled her described captors and "emerged from the desert," she was a page one story cabled abroad by foreign correspondents.[1] |

On May 18, 1926, Christian evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson disappeared from Venice Beach, California after going for a swim. She reappeared in Mexico five weeks later, stating she had escaped from kidnappers holding her for ransom there. Her disappearance, reappearance and subsequent court inquiries regarding the allegation that the kidnapping story was a hoax carried out to conceal a tryst with a lover precipitated a media frenzy that changed the course of McPherson's career.

Disappearance off Venice Beach

On May 18, 1926, McPherson went with her secretary to Ocean Park Beach north of Venice Beach to swim. Soon after arriving, McPherson was nowhere to be found. It was thought she had drowned.

McPherson was scheduled to hold a service that day; her mother Minnie Kennedy preached the sermon instead, saying at the end, "Sister is with Jesus," sending parishioners into a tearful frenzy. Mourners crowded Venice Beach and the commotion sparked days-long media coverage fueled in part by William Randolph Hearst's Los Angeles Examiner and a stirring poem by Upton Sinclair to commemorate the tragedy. Daily updates appeared in newspapers across the country and parishioners held day-and-night seaside vigils. One parishioner drowned while searching for the body, and a diver died of exposure.

Kenneth G. Ormiston, the engineer for KFSG, had taken other assignments around late December 1925 and left his job at the Temple.[2] Newspapers later linked McPherson and Ormiston, the latter seen driving up the coast with an unidentified woman. Some believed McPherson and Ormiston, who was married, had become romantically involved and had run off together.

McPherson's children, Roberta Star Semple and Rolf McPherson, were scrutinized by suspicious news reporters trying to ascertain their degree of distraughtness. Roberta hid in the basement of her parsonage home as news reporters entered the building and began searching though McPherson's room and belongings looking for clues to her whereabouts.[3] Rolf, who had been boarding in a remote farmhouse for the past three years, was besieged by reporters who heard a rumor he might have talked to his missing mother by telephone.[4]

Sighting claims

After her disappearance from the beach, many sightings of Aimee Semple McPherson were recorded.[5] Immediately, there was a report of her driving away from the beach in her Angelus Temple uniform, as witnessed by a Culver City detective.[6] However, this later was confirmed to be a parishioner in uniform; a dark cape and tie over a white nurse's dress, typical of what many female members wore.[7] McPherson "sightings" were abundant, as many as 16 in different cities and other locations on the same day.[8]

The Angelus Temple received letters and calls claiming knowledge on the missing McPherson. One message stated McPherson was gone for a much needed rest and would be back July 16. Another, given by a spiritualist, indicated, while in a trance, she saw McPherson bound and apparently in distress in a cabin.[9]

On June 5 newspaper headlines announced McPherson had been found in Canada, as stated in a telegram message sent by authorities. The sender of the telegram knew McPherson from a revival meeting in Toronto, Canada. Tracked by three detectives, a woman reported to have been the missing evangelist was found in Edmonton, Alberta; arriving there in a Studebaker via Calgary, and followed by another car. The woman checked into the Coronca hotel and it was reported she was "positively identified" by the three operators as the revivalist. It was only after the women was picked up by Canadian authorities and gave proof of her identity as someone else that the sighting report was rescinded on June 7.[10][11] During the period of her disappearance; while there were "various and voluminous claims," of McPherson sightings, none at all came from Carmel-by-the-Sea, a California town that would later dominate the headlines for such sightings.[12]

Ransom demands

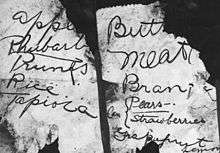

Several ransom notes and other similar communications were sent to the Temple, some of which were relayed to the police; who ultimately dismissed them as fraudulent. For a time, Mildred Kennedy, McPherson's mother, offered a $25,000[13] reward for information leading to the return of her daughter.

The ransom demands sent included a handwritten note by the "Revengers" who wanted $500,000[14] and another for $25,000[13] conveyed by a blind lawyer, Russell A. McKinley, who claimed contact with the kidnappers.[15][16][17] A lengthy ransom letter from the "Avengers" arrived around June 19, 1926, also forwarded to the police, demanded $500,000[14] or else kidnappers would sell McPherson into "white slavery." Relating their prisoner was a nuisance because she was incessantly preaching to them, the lengthy, page and half poorly typewritten letter also indicated the kidnappers worked hard to spread the word McPherson was held captive, and not drowned. Kennedy regarded the notes as hoaxes, believing her daughter dead.[18] She set herself about the task of continuing to raise money for a needed church building expansion which became part of an elaborate memorial service commemorating the evangelist's death. Tearfully, on June 20, Kennedy spoke somberly to the gathered parishioners: "We do not believe that Sister's body will ever be recovered. Her young body was too precious to Jesus." Collection plates yielded $34,910.[19]

Reappearance in Mexico and return to Los Angeles

Shortly thereafter, on June 23, McPherson stumbled out of the desert in Agua Prieta, Sonora, a Mexican town across the border from Douglas, Arizona. The Mexican couple she approached there thought she had died when McPherson collapsed in front of them. She stirred and the couple brought her inside and covered her with blankets.[20] She claimed she had been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held for ransom in a shack by two men and a woman, "Steve," "Rose," [21] and another unnamed man. A fourth person, by the name of "Felipe" stopped by for a visit.[22][23][24] An hour later after reviving her, she drank some water and the husband, R. R. Gonzales alerted the mayor of Agua Prieta, Presidente Ernesto Boubion, to see her. Boubion stated she had grasped his wrist, trembled violently, and asked where she was. She looked ill and appeared agitated, and declined both food and drink. She was transported across the border to Douglas, Arizona, brought by the police station then and was placed in the Douglas hospital. Her shoes were white with desert dust and her hands were covered with grime. A nurse picked some cactus spines from her legs and rubbed some preparation on the toe where a blister had broken. She went on about protection for her 16-year-old daughter and warned her assailants had plans to make off with Mary Pickford and other celebrities.[25][26] At that time no one believed she was Aimee Semple McPherson, the missing Angelus Temple pastor. A reporter heard the claims and visited the hospital. Though, as he said, she was emaciated and barely recognizable, the journalist knew her from covering past revival meetings.[27] Once properly identified, her family and some Los Angeles authorities took a train to see her.

Her statement taken in the Douglas Hospital explained while on the beach near Los Angeles, a young couple approached and asked her to come and pray for their sick child. When she went with them and looked in on the bundle in the back seat of an automobile, they then shoved her into their car. At the same time a cloth was held over her face loaded with a sickly sweet substance; later speculated to be chloroform with an additive.

After awakening, she was no longer clothed in her bathing suit and was wearing a dress. A woman named "Rose," who displayed professional nursing skills, looked after her. Held for a time in what was a boarded up room in a house that appeared to be an urban area, she was later moved to the remote shack in Mexico. Trying to elicit some personal information to prove they had her, one of her captors burned McPherson's hand with his cigar, but felt bad about it and stopped. McPherson's statement gave details on how she escaped the desert shack while her assailants were out on errands. She cut her bonds on a metal can lid, a technique she later successfully demonstrated several times before skeptical reporters;[28] and climbed out the shack's back window. Using a mountain to navigate, she made her way north. She told how she used her garments to shield herself from the afternoon sun and carefully stepped around any shaggy bushes in her path. In the evening, lights from a town guided her to its streets. Terrified by the unexpected savagery of nearby barking dogs behind a fence, she entered the yard of a Mexican couple, R. R. Gonzales and his wife.[29] Her story was transmitted and transcribed across telegraph and phone lines becoming front-page international news.

On the way back to Los Angeles, the train was stopped and boarded by two men who claimed to have earlier seen McPherson during the time she stated she was kidnapped. One man, realizing a mistaken identity, apologized and excused himself after seeing her. However, in a much publicized scene, the other individual; stated he saw her at a Tucson, Arizona street corner 4 weeks earlier in May. By his own admission, he never saw the evangelist in person, only by photograph. The woman he saw in the street wore a tight, low fitting hat shading her eyes and walked in different gait than McPherson used. Yet for him it was those obscured eyes that confirmed his identification. McPherson wrote he was her first experience with such "identifications," others of which were even "more absurd;" and "all were flung to the world in newspaper headlines." Later, this witness was discarded as his sighting came at a time when McPherson was accused by Los Angeles prosecutors to have instead been in Carmel-by-the Sea, California.[30][31]

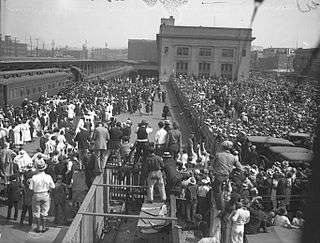

Following her return from Douglas, Arizona, McPherson was greeted at the train station by 30,000–50,000 people, more than for almost any other personage.[32] The parade back to the temple even elicited a greater turnout than President Woodrow Wilson's visit to Los Angeles in 1919, attesting to her popularity and the growing influence of mass media entertainment.[33][34][32]

Already incensed over McPherson's influential public stance on evolution and the Bible, most of the Chamber of Commerce and some other civic leaders, however, saw the event as gaudy display; nationally embarrassing to the city. Many Los Angeles area churches were also annoyed. The divorcee McPherson had settled in their town and many of their parishioners were now attending her church, with its elaborate sermons that, in their view, diminished the dignity of the Gospel. The Chamber of Commerce, together with Reverend Robert P. Shuler leading the Los Angeles Church Federation, and assisted by the press and others, became an informal alliance to determine if her disappearance was caused by other than a kidnapping.[35][36]

In response to an increasing undercurrent of doubt, the leadership of the Angeles Temple debated whether or not to let the matter drop or push for vindication. McPherson welcomed the opportunity for more publicity, since she saw it as a way to expose more people to her vision of Jesus Christ. Her mother, Mildred Kennedy cynically thought the controversy might get away from them and become disruptive to the Temple's activities. Judge Carlos Hardy, an influential friend of the Temple, and McPherson over the stern objections of her mother, Mildred Kennedy and lawyers hired for advice, decided to go to court and present their complaint.

Grand jury inquiries

There were several phases of Los Angeles 1926 grand jury inquiries regarding Aimee Semple McPherson, all conducted by Los Angeles District Attorney Asa Keyes. The first inquiry was about charging McPherson's kidnappers, with indictments made against Steve Doe, Rose Doe, and John Doe,[37] convening on July 8, 1926, and adjourning on July 20, 1926. However, it became immediately apparent the evangelist was being interrogated from a viewpoint of hostile skepticism. Prosecutor Asa Keyes insinuated she was a charlatan who was run out of various cities during her revivals. Quite the contrary, they were wanting return visits and McPherson offered to show news clippings attesting to the success of her work in those locations. Annoyed, Keyes continued, focusing on the belief the disappearance was plot to elicit money from a memorial fund commemorating McPherson's death or for promotional purposes. Her sanity was also questioned, perhaps she might have simply wandered off suffering from amnesia.[38] The inquiry ended determining there was not enough evidence to charge neither alleged kidnappers or the McPherson group for fraud.

The 2nd inquiry, amidst frenzied publicity started on August 3 in response to new developments that suggested cohabitation with ex-employee Kenneth Ormiston in the resort town of Carmel-by-the-Sea instead of being held by kidnappers. It stalled due to the lack of evidence and was considered ended by mid-August with its body of quarreling jurors dissolved by a judge. Later, when a defense witness, Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff, sided with the prosecution as a betrayed co-plotter, another grand jury inquiry was ordered to begin in late September. Testimony and evidence from Carmel-by-the Sea was reintroduced by the prosecution together with their new witness. Their intent was show proof of a conspiracy by the McPherson party to manufacture evidence in bolstering her kidnapping story. The McPherson's defense team, previously overshadowed much of the summer by news publicity favoring the prosecution, was able to comprehensively explain their side of the case during October until they rested their case on the 28th.

On November 3, Judge Samuel R. Blake, was to try the evangelist, her mother and several other defendants in a jury trial case with charges that amounted to criminal conspiracy, perjury and obstruction of justice; set for mid-January 1927. If convicted, the counts added up to maximum prison time of 42 years.[39][40][41] Further statements and information were taken from various witnesses ahead of the projected trial through early January 1927.

Escape through the desert

The first inquiry starting on July 8, read McPherson's statement into the record. Mildred Kennedy broke down and sobbed during the reading which took most of a day to enter. Testimony continued with what allegedly happened in Mexico though the most comprehensive portions, especially from the defense, came later in October.

McPherson's disappearance was concurrent with Mexico transforming itself into a secular socialist state which was even violently enforcing laws prohibiting the teaching of religion in schools along with other religious restrictions that led up to the Cristero War of 1926–1929. Mexican officials were immediate in expressing similar opinions that McPherson could not have been illegally taken onto their land. Even as the woman in the Arizona hospital was just identified as the missing evangelist; on July 23, the same day, Consul General of Mexico, George A. Lubert announced that McPherson could not have been taken across the border against her will. He stressed the impossibility of smuggling a person across the border since it was patrolled with a "strict watch" by both nations.

Governor Abelardo Rodriguiz, told the Associated Press on June 24 he had assigned special police to all border towns immediately after the evangelist's disappearance; and was positive she could not have been carried by force across the border. He was certain she had not been in either Mexicali or in any other part of Lower California since her disappearance May 18.[43][44] However, persons and objects being moved illegally between the US and Mexico was a known problem, with smugglers crossing guns along the length of the border.[45] Additionally, the FBI had previously encountered cross border kidnapping rings before.[46] One of the persons named in McPherson's statement, Felipe, was described as "a huge hulking man." In another case, the federal government was attempting to locate an "Old Felipe " of Mexico City; described as being in charge of a narcotics and a white slavery ring; corroborating that part of McPherson's testimony and the typewritten ransom note received earlier which threatened to sell the evangelist "to Old Felipe of Mexico City."[47][48][49]

Initial, vigorous searches around Agua Prieta did not locate any kidnappers or even the shack where she was allegedly imprisoned. Presidente of Agua Prieta, Mexico, (Mayor) Ernesto Boubion, after examining some foot tracks, expressed his belief she got out of a car 3 miles (4.8 km) from Agua Prieta.[50] Boubion also considered it a "national insult" that a prominent American woman could be kidnapped into his territory.[51]

However, it was revealed, as attested to by his translator, William Appel, that Presidente Ernesto Boubion solicited McPherson for a bribe. When McPherson later returned to Mexico in early July 1926 to assist in looking for signs of her kidnappers, the Presidente wanted to see her privately. With his translator as the only other person in the room, Boubion took her aside and shut the door. He said certain individuals were willing to pay him $5000 to cast doubt on her story though he would back her statement if she paid him the money instead. McPherson wrote:

| “ | Here was a man making a proposition that if he was not paid so many American dollars, he would give a written statement to the effect that my experience never happened.... It was not the last time,...that an unscrupulous person wanted to exact a toll to keep from lying. I walked out of the cafe hardly dignifying the swarthy plotter with an answer. My position seemed to be a signal for every charlatan to gather, in hope of material gain. | ” |

A lawsuit was brought against Boubion by her lawyers for extortion.[52]

Criticism to McPherson's story, in the first grand jury inquiry and further explored later, assumed temperatures, as per Prosecutor Asa Keys, of 120 °F (49 °C),[53] and the inability of walking 20 miles (32 km) over that territory without water. It was being reported McPherson seemed in unusually good health for her alleged ordeal; her clothing showing no signs of what was expected of a long walk through the desert. Prosecutor Asa Keys, while speaking to McPherson during a grand jury session, said; "don't you know it is practically an impossibility for anyone, particularly a woman, to walk over the desert in Mexico in the broiling sun from noon until practically midnight without water? [54] The sheriff of Cochise County, James A. McDonald and police sergeant in Douglas, Alonzo B. Murchison, both expressed opinions about not crossing the expanse without severely damaging garments or footwear. Murchison also said “There is no woman that could make a trip like that and not be near complete exhaustion.”[55][56]

In his affidavit that R.R. Gonzales gave in support of the evangelist, around 1:50 am on June 23; he found an unknown woman "lying on the ground unconscious or fainted, in the gate, with her feet inside and her head out in the street." After getting a flashlight he looked he over, "I thought she was dead at the time, she was cold." Gonzales and his wife picked her up and put her in bed. G.W. Cook, a police officer, affidavit stated "that in affiant’s opinion she was then in a state of complete physical exhaustion."[57]

In the first grand jury inquiry, Prosecutor Asa Keyes also took issue over a watch visible on McPherson's wrist as seen in a photograph while she was in her Douglas hospital bed. She had not taken a wristwatch to the beach and it would be unlikely the kidnappers would let her have one. However, the Mexican couple who found her, the mayor of Agua Prieta, policemen, nurses and any other person she met with, could not recall a wristwatch being in her possession before entry into the hospital. According to McPherson, the watch was obtained sometime during her stay there.[60]

The skepticism was disputed by most other Douglas, Arizona, area residents, including expert tracker C.E. Cross, who testified that McPherson's physical condition, shoes, and clothing were all consistent with an ordeal such as she described.[61][62][63] Cross also noted tracks consistent with McPherson's shoes near an automobile's tire prints outside Agua Prieta, and determined they had nothing to do with each other. The temperature was only 97 °F (36 °C) in the Sonora Desert while another said it was 96 °F (36 °C) as measured in Douglas on June 22, the day of McPherson's desert trek.[58][59] Disgusted at what was happening in the Los Angeles court, Mayor A.E. Hinton, together with 22 representative citizens of Douglas, Arizona, signed a testimonial document affirming their belief in the statements McPherson made.[57]

Several months later, Constable O. A. Ash of Douglas, Arizona, elaborated on the prison shack that could not be located in earlier searches. Together with their Native American tracker, they were able to locate her footfalls again after two miles (3 km) of cattle tracks. He stated Aimee's shack was actually found on August 18, 1926, first seen by his accomplice Lieutenant Gatlitf, lieutenant of the Douglas police department. It was a miner’s cabin near the abandoned San Juan gold and copper mine, 18 miles (29 km) from Douglas. Inside they saw the five-gallon (19 liter) oil can which had been opened with a canopener, "and we could see that the rough edge had been used to cut the bed ticking strips which apparently had bound the woman’s wrists and ankles." He also stated he saw the marks on the evangelist's wrists made by these strips; her ankles were swollen; there were holes in her stockings and one pocket was torn from her gingham dress.[64]

Carmel-by-the-Sea

The grand jury met a second time towards the end of July after new evidence was received on July 22 appearing to have placed McPherson at a northern California seaside resort town during the first part of her disappearance. The prosecution collected at least five witnesses, who asserted to have seen McPherson two months earlier at the Benedict[66] seaside cottage in Carmel-by-the-Sea. The cottage was being rented by Ormiston under an assumed name of "George E. McIntyre". While sightings of the missing evangelist were reported as far away as Canada, no reports at the time came from Carmel.

Los Angeles authorities realized, however none of their witnesses had verifiably seen McPherson in person; only in photographs. The prosecution invited the evangelist to visit Carmel, conveying, if she had nothing to hide, she should present herself to the witnesses for a proper identification. McPherson lawyers, however, prevented her from going to Carmel-by-the Sea as they were concerned the alleged witnesses would identify her from the photos they were given and not from the person they actually saw[67]

The list of persons who testified before the grand jury that they saw McPherson at Carmel included Jennette Parkes, who lived next-door to the cottage. She caught passing glimpses of the woman, wearing a cap and goggles at no closer than about 25 feet (7.6 m); with one sighting estimated as long as two minutes. Later, through the kitchen window, she said, she noticed that the woman had a mass of red hair piled high on her head. Mrs. McPherson was asked to remove her hat, exposing her hair. The witness laughed and said "that's her." Parkes' husband Percy gave testimony he also saw the woman for an estimated total of perhaps 30 seconds. One time he saw her "rush into the cottage", without cap and goggles."[68][69][70]

Another was Ernest Renkert who delivered a load of wood to the cottage. He admitted, though, that he earlier told a judge she was not over 25 and still another judge that the woman, he saw at the Carmel-by-the-Sea cottage was a blonde. McPherson, though, was over 35 and had auburn hair. Renkert stated "When I see a woman I look at her," which elicited a laugh from McPherson and her mother, Mildred Kennedy. He had first read of the $25,000 reward offered for the evangelist's return a week after he first saw the woman.[68][69][70] With pictures of her prominently appearing in the newspapers; the unanswered question McPherson gave in response to all the witnesses stating they saw her there, was "why didn't they report the matter and secure the $25,000[13] reward that was offered for me?"[71][72][73]

In a court encounter McPherson dramatically wrote about later, the door opened again and the prosecutor confidently announced the entry of another witness; William McMichaels, stonemason. He saw "Miss X" more times than all other witnesses put together; and with his intelligent, trustworthy and likable appearance, the stonemason's word was expected to carry great weight. To McPherson, who previously listened to the other witnesses placing her at Carmel-by-the-Sea, he was a new terror. Except for two days, McMichaels labored on the fence of the Carmel cottage throughout May 18–29 during its occupation by Ormiston and his feminine companion. He said he was within ten feet (3 m) of the woman at the bungalow on several occasions.

Directed towards McPherson to answer if she was the lady seen at the cottage, McMichaels requested that her hat be removed. The stonemason peered intently at the evangelist, studying her with intense grey eyes; then settled down in the witness chair. In absolute deathlike stillness, every eye focused on him. "No!" his voice boomed with conviction. McMichaels said: "that is not the woman I saw."

McPherson wrote, "The prosecutor and his staff deflated with almost an audible bang,...their big gun had backfired. The long-heralded witness had become the champion of truth." McMichaels' testimony was reported afterwards by some newspapers as good witness for the McPherson side in the case. Other persons, including at least one other the prosecution erroneously thought would testify for them, also stated the woman seen at the Carmel-by-the-Sea cottage was not McPherson.[74][75]

The landlord of the cottage, H. C. Benedict, wrote on a back of a photo of McPherson that there was nothing about it that reminded him of the woman who was with Ormiston. Benedict testified Joseph Ryan, Deputy District Attorney, tried very hard to get him to identify the woman in his rented cottage as McPherson; however, he could not. When asked about the photos of McPherson, he answered, "he had a whole squad of them up there...and they been pulling these photographs and saying "do you recognize this" and another one "Do you recognize this?" Biographer Raymond Cox, based on H. C. Benedict's testimony, described the method Ryan used to obtain some of his witnesses. Persons were sought who at least had a brief glimpse of the woman with Ormiston. Ryan would take a sheath of photographs taken of McPherson, as provided by the newspapers and then show them to the prospective witnesses, one photograph at a time. Once the prospect finally agreed that a photo of McPherson resembled the woman with Ormiston, Ryan would have his witness identification.[76][77]

Some prosecution witnesses stated that when they saw McPherson in Carmel, she had short hair, and furor ensued she was currently wearing fake hair swatches piled up to give the impression of longer tresses. McPherson, as requested by her lawyer, stood up, unpinned her hair, which fell abundantly around her shoulders, shocking the witnesses and others into embarrassed silence.[78] The prosecution witnesses in general did not get an unobstructed view the woman in the cottage[72] while most of those who saw her without the hat, scarf and "googles," with some speaking at length with her; could not identify "Miss X" as McPherson. August England Carmel's town marshal and tax collector of 10 years, for example, indicated he saw "Miss X" at a range of 8 to 10 feet (2.4 to 3.0 m), at least three times between the May 19 and 29 and spoke with her. She was not wearing a hat and was without "goggles." Asked if the evangelist was the woman he saw there, he said: "Positively not the woman." With his testimony, McPherson wrote of the prosecution, "Gone was the one great chance to bolster up the indefinite vagueness of the examination that had gone on before." [79][80][81] A columnist for the San Bernardino Sun wrote on the selection of prosecution witnesses "without a doubt they are honest in their opinions, but that the sworn servants of the law should try to hang a woman's reputation on such hazy testimony passes understanding." The columnist further added:[82]

| “ | The most important witness, who says he is an engineer by profession, was compelled to admit on the stand that the woman he saw at Carmel he first took to be one that he knew, and later he revised his opinion when he read the newspaper stories of the disappearance of Mrs. McPherson, and after seeing her once on the street there, he came to Los Angeles 75 days later, and declare he identifies her. | ” |

A lawyer later noted the Carmel-by-the-Sea witnesses were being called to identify a woman they saw two months earlier when nothing of an unusual nature took place at the time which would help fix her image in their memory. Testimony concerning "Miss X," the unknown woman seen with Ormiston, varied widely. She was 40 or more, or a girl of not over 25; she had dark eyes, dark hair, and olive complexion or fair skin or blond.[83]

Ormiston admitted to having rented the cottage but claimed that the woman who had been there with him – known in the press as "Mrs. X" – was not McPherson but another woman with whom he was having an extramarital affair.

The grand jury reconvened on August 3 and took further testimony along with documents from hotels, all said by various newspapers to be in McPherson's handwriting using assumed names. However, the collected paperwork could not link Ormiston to McPherson. Upon further investigation, amidst all the persons and their aliases listed in the case, the only individual showing no reluctance in signing her own name to any hotel register, reporters found, was Aimee Semple McPherson.[84][85][86]

The Carmel cottage was further checked for fingerprints, but none belonging to McPherson were recovered. Two grocery slips found in the yard of the cottage were studied by a police handwriting expert and determined to be McPherson's penmanship. While the original slips later mysteriously disappeared from the courtroom, photo-stat copies were available.[87] The defense had a handwriting expert of their own and claimed to have a photograph of the well publicized slips which differed from the police photostat. They contended the reproduction "had been maliciously tampered with" to resemble the evangelist's handwriting.[88] The slips' suspicious origin was also questioned. The original slips would have been in the yard for two months, surviving dew, fog, and lawn maintenance before their discovery by deputy DA Ryan.[89] Frustrated with his own witnesses and evidence, at the close of one of the day's sessions, prosecutor Keyes disgustedly threw a stool top after the departing courtroom crowd.[90]

Prosecutor Keyes reasoned that, without fingerprints conclusively placing McPherson at the scene, the case at Carmel-by-the-Sea "had blown up".[91] Since not enough evidence from Carmel-by-the-Sea was obtained to proceed to trial, by mid-August the investigation appeared to be at an end. After a defense witness decided to instead testify for the prosecution, another grand jury investigation was formed starting in late September 1926.

Final grand jury inquiry phase and dismissal

With one of the critical defense witnesses, Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff, turning state's evidence, the prosecution submitted their file to the judge. On November 3, Judge Samuel R. Blake, was to try the evangelist, her mother and several other defendants in a jury trial case in Los Angeles, set for mid-January 1927. If convicted, the counts added up to maximum prison time of 42 years.[39][40][92]

The bulk of the testimonies had since taken place with the defense resting its case on October 29. However, new developments continued afterwards. The prosecution wanted to question H. C. Benedict to see if he knew anything about the contents of a blue steamer trunk purportedly belonging to Ormiston confiscated in September, however, the landlord of the cottage died in mid-November. Apart from affidavits and messages, Kenneth Ormiston still had not given testimony. More importantly, Wiseman-Sielaff appeared to be giving new information concerning the conspiracy implicating McPherson and her circle of friends and acquaintances.

By late December, however, the prosecution determined their new star witness Wiseman-Sielaff, could no longer be a considered a credible witness. Without her, District Attorney Asa Keyes considered other evidence found insufficient in continuing to prosecute the case. Together with his assistants, Keyes signed and submitted the statement document to have the case dismissed. In it Keyes conveyed that without Wiseman-Sielaff's testimony, the alleged conspiracy was impossible to prove. He added "Reputable witnesses have testified sufficiently concerning both the Carmel incident and the return of Mrs. McPherson from her so-called kidnapping adventure to enable her to be judged in the only court which has jurisdiction —the court of public opinion. "

The Examiner newspaper reported that Los Angeles district attorney Asa Keyes had dropped all charges against McPherson and associated parties on January 10, 1927.[93][94][95]

Regardless of the court's decision, months of unfavorable press reports fixed in much of the public's mind a certainty of McPherson's wrongdoing. Many readers were unaware of prosecution evidence having become discredited because it was often placed in the back columns while some new accusation against McPherson held prominence on the headlines. In a letter he wrote to the Los Angeles Times a few months after the case was dropped, the Reverend Robert P. Shuler stated, "Perhaps the most serious thing about this whole situation is the seeming loyalty of thousands to this leader in the face of her evident and positively proven guilt."[96]

Some supporters thought McPherson should have insisted on the jury trial and cleared her name. The grand jury inquiry concluded while enough evidence did not exist to try her, it did not indicate her story was true with its implication of kidnappers still at large.[97] Therefore, anyone could still accuse her of a hoax without fear of slander charges and frequently did so. McPherson, though, was treated harshly in many previous sessions at court, being verbally pressured in every way possible to change her story or elicit some bit of incriminating information.[98] Moreover, court costs to McPherson were estimated as high as US $100,000 dollars.[99][73] Payments to lawyers and other defense costs, according to the IRS, were not part of church operating expenditure and therefore constituted a tax liability that the Angelus Temple had to raise money to cover. A jury trial could take months. McPherson moved on to other projects. In 1927 she published a book about her version of the kidnapping: In the Service of the King: The Story of My Life.

Two prominent defendants

Several defendants were charged as a result 1926 grand jury inquiries, among them Aimee Semple McPherson, Mildred Kennedy, Kenneth G. Ormiston, and Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff. Another was about to be questioned, Dr. A. M. Waters, who was implicated by Wiseman-Sielaff as being involved in McPherson's alleged Carmel coverup; and committed suicide when he learned of the grand jury's interest in him.[100]

Kenneth G. Ormiston, and Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff stood out as being the least questioned and the most questioned persons by the grand jury inquiry, each nevertheless receiving headlines and huge amounts of publicity. Ormiston shunned the spotlight and Wiseman-Sielaff craved it, inserting herself into the McPherson grand jury inquiry at a time when it stalled and prosecutor Asa Keyes was ready to drop it.

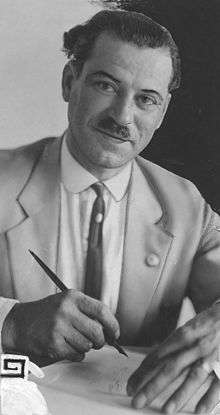

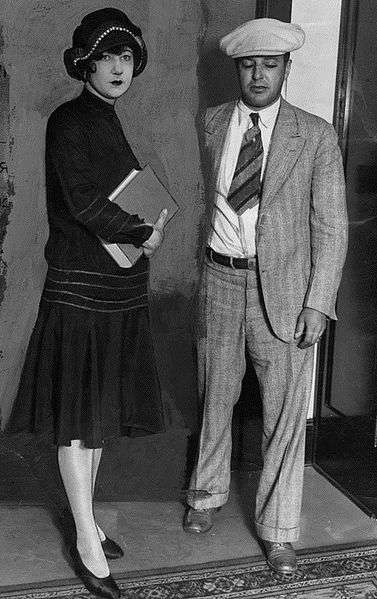

Kenneth Ormiston

In that he was McPherson's accused lover, allegedly assisting in the kidnapping fraud, Kenneth G. Ormiston was a prominent defendant in the 1926 grand jury inquiry. He had been McPherson's radio operator and was crucial in getting her programs on the air. He was described as about 5 feet 11 inches (180 cm) tall, bald, slender, and good-natured with a wonderful disposition.[101] He also had a distinctive limp that frequently identified him more than any other feature. During the time of McPherson's disappearance, newspapers freely speculated about him and the Los Angeles DA office initiated various manhunts accompanied by front page headlines, searching for the elusive radioman.[102] Though the Los Angeles prosecution and two city newspapers spent lavishly to romantically connect McPherson with Ormiston, citing questionable circumstances, no conclusive evidence attesting to them being lovers could be uncovered.[103] To some law enforcement officials outside of Los Angeles, the pursuit of Ormiston was done for publicity.[104][105][106]

McPherson appeared to be friendly with Ormiston and it was insisted their relationship was strictly professional.[107] Marital problems with his jealous wife led to marriage counseling conducted by McPherson. Around late December 1925, he left his job at the Angelus Temple, then disappeared, prompting his wife to report him missing in January, 1926. Some rumors placed him in Europe with McPherson, however, during that time, he called the Angelus Temple from Washington State in March where he was employed as a car salesman.[35][108] McPherson's daughter, Roberta, joined her there in Europe to prevent further gossip.

McPherson's May 18 disappearance coincided with Ormiston taking possession of a cottage he rented for three months in a seaside resort town of Carmel-by-the Sea. Rumors developed his companion, that he had been seen elsewhere with, was the missing McPherson, and police sought Ormiston. He immediately turned himself into authorities on May 27, denying that he "went into hiding;" and stated his name connected to the evangelist was "a gross insult to a noble and sincere woman." [109] Though he did not mention Carmel to head off unwanted attention there, he gave details of his previous movements.[110] Since his name was now inserted into the McPherson case, Ormiston was worried about being followed around.

His concerns materialized two days later. On the evening of May 29, near Santa Barbara, a reporter tracked Ormiston's blue Chrysler sedan coupe, and flagged it down. After examining the driver and his female passenger, the reporter determined while the man was Ormiston, he could not identify the woman, "Miss X," as McPherson.[111] As the result of the incident, a Santa Barbara Morning Press article headline later read: Road Watched for Ormiston and Evangelist.[112]

To escape further media attention,[113] Ormiston vacated his Carmel-by-the-Sea cottage and placed his blue sedan in a storage garage.[114] After arguing with "Miss X," he left her in a hotel, abandoned California and traveled to Colorado, Illinois, New York, Philadelphia and other locations. The hotel operator and a garage employee were later able to identify Ormiston as the man who patronized their respective establishments. Both persons were certain the woman with him was not McPherson. The garage employee remarked the woman did, though, have a striking resemblance to the evangelist.[115][116]

In late July, reporters and police received information a person who fit Ormiston's description had rented a Carmel-by-the-Sea cottage in May. In response to the intense news coverage of a half a dozen or more witnesses suddenly alleging they saw McPherson there, Prosecutor Asa Keyes launched another manhunt for Ormiston. McPherson herself pleaded through the papers for Ormiston to clear the matter up. Annoyed, Ormiston sent a letter from New York to Asa Keyes denouncing the treatment received from newspapers and officials as “nasty publicity and subsequent persecution by self-styled investigators," and that he had no intention of appearing before the Los Angeles grand jury.[117] He released a lengthy statement to the police and several newspapers. Affirming "Miss X" was not McPherson, he added his companion had "the same general build and brown hair color as the evangelist."[118]

Along with insufficient evidence acquired at Carmel,[119] Ormiston's affidavit was believed to have influenced the discontinuance of the second grand jury investigation of the McPherson case around August 11.[120] However, developments occurred with a new prosecution witness, Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff; and renewed efforts were made by Los Angeles authorities to bring Ormiston back to Los Angeles.

On October 29, after the defense rested its case, the next day, District Attorney Asa Keyes announced the September discovery of a large blue steamer trunk allegedly owned by Ormiston and thought to be full of McPherson's clothing. On November 8, 1926, a Kansas City private detective, described as a "go between" for Ormiston, transmitting him money and messages; stated the trunk was a "fake."[121] Ormiston, who was still eluding authorities to avoid being pressured to reveal Miss X's true name; on November 19, said the "trunk is bunk." [122] Some of the clothing was found to be the wrong size for the evangelist.[123] The trunk became an object of jokes, in reference to anything unwanted, unknown, or lost as being laid away in that big blue trunk.

In December, Ormiston was found living quietly in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, tracked there by newsmen. Papers describe him being taken without resistance by police while sitting at a typewriter.[124] A Harrisburg detective characterized the affair as a "publicity stunt," but decline to elaborate. Among Ormiston's personal effects were found five diplomas from five radio schools and letters implying he had a wife in Brazil.[104] He was escorted to Chicago, Illinois with intent to be transported to Los Angeles. Asa Keyes made statements to “do everything in his power” to extradite Ormiston. However, he did not stop in Chicago to pick him up though he traveled near there on his way to and from Washington, D.C; conveying Ormiston was a "sidelight" to the investigation. The Chicago police chief denounced Keyes for "yelling to high heaven for his apprehension" and when the fugitive Ormiston was "within reach," he is now described by Keyes as being of minimal importance.[106][125] The Chicago police chief lacked proper documents for further action and to the annoyance of Los Angeles officials, Ormiston was released. When the warrant was finally obtained; Chicago police were ready to transport their expected prisoner, Ormiston, to Los Angeles [126] In the meantime, Ormiston appeared in Los Angeles surrounded by newsman and was greeted by the entire prosecution staff. Affably, amidst the flashbulbs of photographers, Ormiston accepted his served warrant. His bond was set at $2,500.[127]

Ormiston declined to answer any questions from the numerous reporters, stepped into Keyes office and typed out his statement. He desired not to complicate the situation since "intrigue and hokum were as thick as San Francisco fog." He maintained he was not at Carmel-by-the-Sea with Mrs. McPherson, stated he violated no conspiracy laws and was not afraid to face trial.[128] In early January 1927, Ormiston testified and gave the name of Elizabeth Tovey, a nurse from Seattle, Washington, as the person who was "Miss X" and his female companion and the woman who stayed with him at the seaside cottage on May 19–29 in Carmel-by-the Sea.[129] A few days later, on January 10, 1926, all charges were dropped against Kenneth Ormiston, Aimee Semple McPherson and all remaining defendants.

Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff

Keyes was about to drop the inquiry in mid August when fingerprints belonging to McPherson could not be found at the Camel-by-the Sea cottage. He determined other evidence at Carmel was too vague for a successful perjury prosecution against the defendants.[130] An unexpected opportunity, though, invigorated the case when a defense witnesses appeared to flip. Keyes thought he now had a direct eye-witness account of the conspiracy conducted by McPherson, Kennedy, and Ormiston to defeat justice by manufacturing false evidence. The chief witness against McPherson was now Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff. Based on her testimony, Keyes ordered a new grand jury investigation.[131]

Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff introduced herself to McPherson and declared she was in Carmel as a nurse for her twin sister who was Ormiston's mistress; and because they somewhat physically resembled McPherson; were being misidentified as the evangelist. McPherson embraced Wiseman-Sielaff as an important witness who would exonerate her and for a time she was a guest at the Angelus Temple parsonage. Kenneth Ormiston also signed a letter around September 8 that his companion was a sister of Wiseman-Seilaff, confirming her initial story. Later, Wiseman-Sielaff's was caught for passing bad checks and blamed it on her twin sister.[132] When her story became untenable, she requested that the Angelus Temple post her bail, but they refused. Wiseman-Sielaff then said McPherson paid her to tell that story about what happened at Carmel-by-the-Sea and assist in hiring someone to pose as "Miss X." She was charged as a defendant in the case in November because she admitted her alleged role as an alibi for McPherson at Carmel and sided with the prosecution for immunity.

As the grand jury inquiry progressed, Wiseman-Sielaff implicated one of McPherson's lawyers, Roland Rich Woolley, for inappropriate conduct when they lived in another state where she said they went to school together. The accusations forced Woolley from the case. Eventually it was proven Wiseman-Sielaff lied about the relationship, the lawyer Woolley gave evidence he had not met Wiseman-Sielaff until August 15, 1926.[133] According to Woolley who was visiting a judge in his office at Salinas on August 15; Wiseman-Sielaff and Virla Kimball, her twin sister, voluntarily appeared there and signed an affidavit attesting that she and her sister were at Carmel-by-the-Sea with Kenneth Ormiston. A cab driver confirmed the presence of the two women there. It was purported by the defense Kimball might have been Ormiston's "Miss X." On May 19, the date Ormiston and the mystery woman appeared at the cottage, it was confirmed Kimball was at nearby Alameda County filing for divorce. She also admitted to being Salinas on August 15; but was not in the judge's office, stating she did not sign any such affidavit and threatened to sue McPherson if she were drawn into "this horrible case."[134][135] Wiseman-Sielaff inserted yet another sister as "Miss X" into the inquiry, Rachel Wells of Philadelphia, as the person who actually signed the affidavit.[136]

In the meantime, another woman came forward, Babe Daniels, 20; of Chicago, IL; stating she was "Miss X" at Carmel; giving some the impression the prosecution was now awash in "Miss X's." Later, she claimed being in on McPherson plot working with Wiseman-Sielaff with the promise of never having to worry about money again. Prosecutor Keyes rejected Daniels' story "as a tissue of lies" and cut her loose with a stern rebuke to anyone else attempting such a fraud would be exposed by his office."[137][138] Criticism erupted and a news columnist wrote:[82]

| “ | Why not prosecute all perjurers, instead of devoting all his attention to one whom every attendant circumstance suggests isn't a perjurer at all, but simply telling the truth and making the prosecution ridiculous? | ” |

Wiseman-Sielaff declared she made a note in her memorandum book regarding money sent, on behalf of McPherson, to Rachel Wells on August 4. However, when asked to produce the memorandum book for examination, Wiseman-Sielaff said she had destroyed the book.[139] Her testimony became more inconsistent as she was further queried in December. It was revealed that Wiseman-Sielaff once spent time in a Utah mental institution.[140]

Keyes, whose case relied totally on this witness to prove the alleged conspiracy, realized Wiseman-Sielaff was giving false testimony against Mrs. McPherson. Keyes briefly considered charging Lorraine Wiseman-Sielaff, with perjury,[141] as her testimony kept the inquiry going for another six weeks, costing $100,000 [142] and yielded nothing, However, for all defendants, he submitted to the judge for case dismissal.

Issues with the prosecution

The grand jury investigation against Aimee Semple McPherson adversely affected the careers of several Los Angeles officials including District Attorney Asa Keyes, Assistant Deputy District Attorney Joseph Ryan, and Chief of Detectives Captain Cline. All three were already rumored to have inappropriate connections to the local underworld, with Ryan receiving an affidavit regarding his role in helping to facilitate protection rackets by acquitting defendants.[143] Vice in general was readily flourishing under Keyes and he legalized slot machines which was later rescinded by his successor. Keyes was also known as a "secret drinker" in Prohibition Los Angeles, patronizing a back room in the tailor shop of Ben Getzoff who had a steady supply of liquor.[144] Keyes also had other issues going on in the middle of the inquiry; in another case he was charged with, and cleared of embezzlement.[145][146] It has been suggested by sources within the Foursquare Gospel Church, McPherson's work grated contrary to their corrupt police interests and in part may have been a motivating factor in the prosecution's unconventional handling of the grand jury inquiry.[147]

Assistant Deputy District Attorney Joseph Ryan

In the Douglas hospital, as he helped to question the convalescing evangelist, Assistant Deputy District Attorney Joseph Ryan enthusiastically professed his faith in McPherson's story. He even said he could make the desert trip without scuffing or marking his commissary shoes.[148][149] Later, in Los Angeles, Ryan testified though, he knew McPherson was a "fake and a hypocrite" the first time he saw her in the hospital.[150] Ryan was assistant to District Attorney Asa Keyes, and essentially did much of the legwork in building the case against McPherson. The defense contended both Ryan and his father-in-law, Captain Herman Cline, neglected their duty by disregarding evidence unearthed by border authorities that substantiated the evangelist’s version of her re-appearance.[151] The declaration by W. A. Gabrielson, chief of police of Monterey, said that "Mr. Ryan's conduct of this case was most unethical" referring to the methods Ryan used, among them entering the cottage in Carmel-by-the-Sea; without a warrant, and without any local official present. Of particular interest among the seized pieces of evidence was a medicine bottle; because it was dated May 25, 1926 and inside the timeframe Ormiston and "Miss X" occupied the cottage. Again without warrant, demands were then made of the druggist and prescribing doctor about the medicine's user.[152] As it turned out, the bottle belonged to the landlord, H. C. Benedict, and contained a "commonplace preparation." Keyes, thought all the evidence obtained at Carmel-by-the-Sea was too vague for a successful prosecution for perjury and was ready to quit the case. Ryan met with his superior Prosecutor Keyes and presented his "ace in the hole evidence" for continuance at Carmel-by-the-Sea. What Ryan offered was in the form of a receipt for a telegram said by him to be in McPherson's handwriting, signed by her at the Carmel cottage with two related witness identifications.[153]

Without fingerprints, Keyes was unconvinced there was sufficient evidence; and early August, ordered witness subpoenas to be suspended along with any further investigation at Carmel-by-the Sea.[153] However, Ryan went over the head of his superior, and publicly announced the mystery solved and the case over, that the kidnapping was a ruse.[154] It was then expected more would be done with the inquiry. For that breech of procedure, Ryan also had the ire of Judge Keetch directed at him since such an accusation represented "a bald and sordid accusation against a woman who has insisted that a crime had been committed against her."[155] Tension between the Ryan and Keyes increased; and Ryan was out, sent back to prosecute pickpockets and other common criminals.[156] The two witnesses, the telegram messenger and a Salinas garage-man, contrary to what Ryan contended; later denied "Miss X" was the evangelist.[157]

Chief of Detectives Captain Herman Cline

A woman who ran an illegal bootlegging saloon boasted of being the sweetheart of Chief of Detectives Captain Herman Cline.[143] Father-in-law to Deputy District Attorney Joseph Ryan, Captain Cline was in on the investigation from the time of McPherson's disappearance. Cline like Ryan initially professed faith in McPherson's account of abduction and escape, earning the headlines Cline Believes.[158] The description of the shoes when taken from McPherson was cataloged "uppers showed slight wear and the soles were scuffed; leather in the insteps was bright and bore markings like grass stains." Cline, however, was quoted as stating to Ryan, "You saw those shoes, the grass stains on the instep, what is so rare as a blade of grass on the desert in June?" [159][160] Lore developed of there being no grass in the desert and that McPherson's shoes and other garments from her desert trek were in pristine condition.[161] However, McPherson had been photographed ankle deep in scrub grasses while looking for her tracks;[162] and the area was host to cattle drives. McPherson's statement, published in the papers; included approximate weight, height, age, eye and hair color; complexion and mannerisms of each of her captors. In later remarks attributed to Cline, he expressed skepticism, for example stating only having limited success in getting get any details from her regarding the kidnappers' appearance.[163][158] In late July, Captain Cline together with deputy DA Joseph Ryan, canvassed Carmel-by-the-Sea for witnesses alleging they saw McPherson there. On August 22, Cline was jailed for drunk driving after running into another car with his police vehicle.[164] Considering his role in the grand jury inquiry, that he should be found in such a condition during Prohibition, was especially disconcerting to the Angelus Temple. Their complaints forced the Los Angeles police department to act and Cline was removed from the case. A period author scolded the Temple for their reaction. Nancy Barr Mavity, an early McPherson biographer; wrote of the drunk driving incident "an error not altogether unprecedented to members of the police departments as to other human beings."[165]

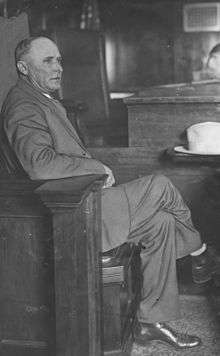

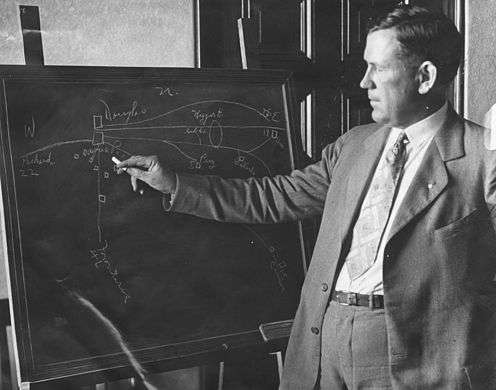

District Attorney Asa Keyes

District Attorney Asa Keyes led the prosecution. He was once a featured speaker at the Angelus Temple and at the time Mildred Kennedy, McPherson's mother; considered him a fair and just man.[80] Overall, McPherson enjoyed a favorable relationship with law enforcement and after the 1926 grand jury investigations were over, police were directing destitute people to the Angelus Temple's commissary for help. That she should have become a target, as she saw it, of such an intense legal smear puzzled her, and she framed it in the context that the Los Angeles prosecution was being controlled by diabolical forces seeking to bring herself and the Angelus Temple to ruin.[166] Biographer Daniel Mark Epstein explained Keyes was a public servant, responding to the pressures of many in the Los Angeles constituency who thought McPherson was making their city a laughingstock.[167]

Sources in the Temple as per Raymond Cox, his own opinion and those of her lawyers, was that Keyes sought to elevate himself as an invincible prosecutor.[168] Keyes conducted the grand jury inquiry in such a way that afforded the evangelist most detrimental public exposure possible, including releasing details of a prosecution witness's testimony to the press; while honoring the code of grand jury secrecy only when it came to the defense side.[169] He was known for winning convictions, but six persons he sent to prison were found to be innocent and pardoned by California's state governor, Friend Richardson. The governor reminded prosecutor Keyes it was his duty to seek justice not convictions, as currently the prosecution office seemed more interested in making a record than they were in acquitting the innocent. Richardson understood pardons for the same district attorney could occur once or even twice under an administration but six times was inconceivable.[170]

After months of testimony and investigation Keyes lacked evidence he so earnestly sought to successfully prosecute the McPherson party in a jury trial. Therefore, on January 1927, he asked for case dismissal. He said, referring to his own side, he was through with perjured testimony, fake evidence and ...he had been duped and a (juried) trial against McPherson would be a futile persecution.[171] After so much media buildup, it was wondered by some what McPherson did to force the abandonment of the "airtight" case against her. Keyes himself came under scrutiny.

Alternate theories circulated about the real reason for the dismissal. One story, purportedly from a secret FBI file, conveyed newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, was blackmailed by the evangelist who threatened to publicize a story she heard about him murdering movie producer Thomas H. Ince in 1924; and for being in an adulterous affair with actress Marion Davies. Hearst, fearing that such stories could damage his reputation, then pressured Keyes to drop the case.[172] These incidents, though were previously part of the public record. Thomas Ince reportedly died of by heart failure brought on by acute indigestion and already there was a run of news gossip concerning Hearst and speculated suspicious circumstances surrounding Ince's death. Davies was a companion to Hearst since 1917; previously enduring publicized scandals about it. Moreover, such scheming was contrary to McPherson's previously known behavior as attested to by others. Guido Orlando a promoter who made Greta Garbo a legend, wrote of McPherson: "She was not a bigot, she did not pry into people's private lives,... She was in all the time I knew her incapable of malice toward anyone."[173][174][175][176] Other rumors spread that she simply bribed Keyes to flush the case with "hush" monies amounting from $30,000 to as much as $800,000. Details and the sources of the various rumors were ambiguous, with little evidence forthcoming to establish credibility.[177][178][179]

In late 1928, the Los Angeles County Grand Jury began looking into the possibility that Keyes had been bribed to drop charges against McPherson. An investigation was started and Keyes was acquitted.[180] In another case where Asa Keyes appeared as a witness, he again was asked about the dismissal. Keyes reiterated that it was because of Lorraine Wiseman-Seilaff; stating no prosecutor has the right "to defile the courts" with known perjured testimony so absolutely unreliable as Wiseman-Seilaff gave. Any further effort to prosecute "could not be done with honor or with any reasonable hope of success." Judge Albert Lee Stephens granted the request for case dismissal.[181][182]

Asa Keyes, went on though, to be convicted of bribery in an entirely unrelated case. There were witnesses, diaries and ledgers with handoffs recorded; evidence Keyes could not defend against. Involving Ben Getzoff and his tailor shop backroom transactions, Asa Keyes was charged with accepting gifts and cash to secure acquittals for several individuals; and sentenced in 1929.[183] McPherson later visited him in San Quentin Penitentiary to wish him well.

Other controversies with the inquiries

Misleading news coverage

In Los Angeles, ahead of any court date, McPherson noticed newspaper stories about her kidnapping becoming more and more sensationalized as the days passed. To maintain excited, continued public interest, she speculated, the newspapers let her original account give way to rain torrents of "new spice and thrill" stories about her being elsewhere "with that one or another one." It did not matter if the material was disproved or wildly contradictory. No correction or apology was given for the previous story as another, even more outrageous tale, took its place.[184]

A newspaper editorial crossed the boundaries of publication decency for U.S. Postal Inspectors when 75 year old Abraham. R. Sauer, of the San Diego Herald, wrote a lurid column about the evangelist and her purported "ten days in a love shack." He was charged with sending obscene literature through the mails. Though acquitted, four newspaper vendors selling the banned publication paid fines. Another publisher who reprinted and mailed the July 29 edition of the Herald was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth Federal Prison.[185][186][187]

Prosecution witness grocery delivery boy Ralph Swanson stated McPherson answered the door when he delivered groceries to a home there. In an interview, as released by a newspaper, he stated seeing three physicians leaving the Carmel cottage late one night. The names of the three doctors, prominent citizens of Carmel, were published. A defense lawyer stated this gave weight to rumor that the ten day visit was for an abortion. The news article created the belief the three prominent citizens of Carmel made an unprofessional call and participated in felonious conduct. The office records of a San Francisco physician suspected of being an abortionist were also ransacked by newspaper representatives. The defense chided the witness as an inexperienced youth giving a thoughtless and false statement. McPherson's near death medical operation in 1914, which prevented her from having more children, was already part of the public record. When challenged about the abortion claim with a request to pay for the medical exam to prove it, the newspaper which printed the story backed down.[188][60][189]

Prosecution witness retired engineer Ralph Hershey, was described in some papers as a star witness for the state, however, different testimony in court was given than what was reported he would give. As published in various papers, Hershey said he was driving along a narrow lane in Carmel-by-the-Sea when two persons, whom he recognized as Mrs McPherson and Ormiston came along the path. He was forced to stop his machine until they walked around.[190]

When he got to court in September, however, his story did not include Ormiston or stopping his car. Hershey explained while driving, he saw a woman approximately 100 feet (30 m) away near a street corner wearing a tight, low hat. He later visited a friend and they agreed the woman was a local resident; who sold that friend his house. Hershey spelled the name of the local woman for the lawyer cross-examining him. Two and a half months later, after a newsman interviewed him, Hersey decided instead the woman was the evangelist. To confirm his identification, on August 8, he traveled to the Angelus Temple and at a distance of around 100 feet (30 m), he saw Mrs. McPherson. Hersey explained it was the large, open, brilliant eyes which clenched the identification for him. The lawyer asserted, without a demonstration, he did not think it was possible at that distance for Hershey "to have seen the shape of her eyes, little less their color, peculiar or otherwise."[191]

Mollifying taxpayers over failure to bring the case to trial in spite of considerable expense; prosecutor Asa Keyes, in his closing statement, made it clear that the investigation was assisted and largely underwritten by the area newspapers. Though many thought the newspaper investigations exposed McPherson was in Ormiston's company at Carmel-by-the Sea during the period of her disappearance;[192] Keyes stated evidence collected there was too vague and inconclusive to pursue further action against anyone on a perjury charge.[119][193]

Shortly after the dismissal of the case, on January 18, 1927, Constable O. A. Ash of Douglas, Arizona was interviewed by a special staff correspondent of the San Bernardino Dally Sun. Constable Ash maintained the press withheld important facts from the public and even gave deliberate misinformation regarding the evangelist's kidnapping story. The papers denied, he said, there being bind marks from the kidnapper's restraints on the evangelist's wrists, though he saw the marks himself. The country, where he back trailed McPherson's 20-mile (32 km) trip through, he described as grassy and ideal pasture land with plenty of springs of water. He conveyed the maximum temperature was around 96 °F (36 °C) . The scorching sands, described in many papers, and brush that would tear clothes and scratch shoes, the constable said, was not present in the region McPherson traversed. He described the papers reporting alleged testimony by witnesses even before they took the stand. Ash stated he knew little concerning the pastor and her work and said she was a " victim of much misrepresentation."[194]

Judge Arthur Keetch of the Los Angeles Superior Court, who presided over one of investigating grand jury bodies he later dissolved, stated on a later date, he thought the papers "were running pretty wild at that time." He was annoyed that secret proceedings of his grand jury was being divulged to the public through the press[195] California grand jury members are bound by law not to discuss the case to protect the integrity of the process in determining if there is sufficient cause for a formal juried trial. The Reverend Robert P. Shuler was told as much by a newspaper in response to an open demand he made for more disclosure in the ongoing inquiry.[196]

Reflecting on that period in his memoirs, Former attorney general of California Robert W. Kenny stated "nothing ever sold more newspapers in Los Angeles than the Aimee affair" and Aimee's only real crime "was that of minding her own business, but that was more than our local bigots could bear." [197]

Evidence lost

The 1926 grand jury inquiry was also known for catalogued evidence that was inexplicably lost. Among the pieces that came up missing:

1. A page long, handwritten demand for $500,000 "Revengers" signed ransom note mailed on May 24 from San Francisco to the Angelus Temple. It was passed on to the police and later discovered to be missing from their locked evidence files in October. The district attorney's office claimed the missing note was written in "disguised handwriting" to help support the plot of McPherson being kidnapped. Because he was in San Francisco on May 24 and 25; and the handwriting and language were those of an "educated person," Kenneth Ormiston was the purported author and this claim was passed on to the press. Photstats previously taken of the note were available to the state; though, nothing in court was presented actually tying Ormiston to the document.[198][199]

2. On July 4, a typewriter placed in storage in a federal building could not be located when it was later sought to test its keys against a sampling of one of the ransom notes demanding $500,000 received by the Angelus Temple. Federal post office inspectors launched a thorough search in an attempt to locate the missing machine. Two different typewriters were used to produce the note in question. The missing typewriter was one of four being examined as possible devices used in the production of the note.[200]

3. The much published grocery slips, found at the Carmel-by-the-Sea cottage and asserted by the prosecution to be in McPherson's handwriting; mysteriously disappeared from the courtroom in early August. They were last seen being examined by a juror who left the courtroom on a break. Some speculated the juror was sympathetic to McPherson and dropped them down a toilet while in the restroom.[201][202] The juror was investigated and determined to have no connection with the McPherson party and the loss of the grocery slips determined an accident. Mildred Kennedy purported assistant DA Ryan might have disposed of them himself.[203] The defense made a serious accusation against the prosecution stating the police photostats of the grocery slips, as supported by several area photographers, did not match the photograph taken of them. Their contention was, the photostats, which were in police custody, were altered to look like the evangelist's handwriting.[204][88]

4. A big, blue steamer trunk purportedly belonging to Kenneth Ormiston, was confiscated in September from a New York hotel. Its contents were inventoried and the trunk sealed. Upon arrival in Los Angeles, Prosecutor Asa Keyes checked its contents against the inventory list, however, several articles of clothing were missing.[205][206]

Publicized stories of evidence being lost in the case was so frequent that Rev. Robert P. Shuler was prompted to comment: "...that someone is lying and that Aimee won’t be the only one mixed up in the dirty mess."[207]

H.L. Mencken

H. L. Mencken, who had been covering the case also commented on the media, writing since many of that town's residents acquired their ideas "of the true, the good and the beautiful" from the movies and newspapers, "Los Angeles will remember the testimony against her long after it forgets the testimony that cleared her."[208]

In the McPherson case, H. L. Mencken observed the grand jury proceedings becoming quite public. A vocal critic of McPherson,[208] Mencken wrote of her, "For years she toured the Bible Belt in a Ford, haranguing the morons nightly, under canvas. It was a depressing life, and its usufructs were scarcely more than three meals a day. The town [he refers to Los Angeles] has more morons in it than the whole State of Mississippi, and thousands of them had nothing to do save gape at the movie dignitaries and go to revivals".[208] Mencken had been sent to cover the trial and there was every expectation he would continue his searing critiques against the evangelist. Instead, he came away impressed with McPherson and disdainful of the unseemly nature of the prosecution.[209]

H. L. Mencken determined the evangelist was being persecuted by two powerful groups. The "town clergy" which included Rev. Robert P. Shuler, disliked her, for among other things, poaching their "customers" and for the perceived sexual immorality associated with Pentecostalism. Her other category of enemies were "the Babbits", the power elite of California. McPherson's strong stand on Bible fundamentalism was not popular with them, especially after taking a stand during the 1925 Scopes trial which gave "science a bloody nose." In addition McPherson was working to put a Bible in every public school classroom and to forbid the teaching of evolution. The Argonaut, a San Francisco newspaper, warned these actions made her a threat to the entire state which could place "California on intellectual parity with Mississippi and Tennessee."Mencken later wrote: "The trial, indeed, was an orgy typical of the half-fabulous California courts. The very officers of justice denounced her riotously in the Hearst papers while it was in progress."[208]

Theories and rebuttals

The Los Angeles prosecution office purported McPherson left the beach with Kenneth Ormiston and stayed with him at Carmel-by-the-Sea for 10 days. Because they were almost identified by a reporter who stopped their car, the two fled California at the end of May, holed up somewhere for most of June; then made their way though Arizona to Mexico where she was dropped off outside of Agua Prieta.

Telegraph operator William Blevins supplanted this theory when he declared he identified McPherson from photographs. He compared handwriting from his logs to samples printed in the newspapers from the grocery slips found at the Carmel-by-the-Sea cottage yard. He said she came into his office at Gila Bend, Arizona, on June 15 and sent a message to Tucson, Arizona; saying an automobile had broken down and she was taking a train. The prosecution confirmed his findings, and subpoenaed two more local witnesses who claimed they saw the same woman; and announced it in the news.

The defense had a surprise witness, one the angry prosecution tried to prevent from appearing as she was presented out of turn at the inquiry. Stymied by objections from the prosecuting attorney, she was effectively silenced until Judge Samuel R. Blake intervened and allowed her to speak. The wife of an airman stationed in the Philippines, Mrs. Gail X. Koontz, said it was she, and not the evangelist, who sent a telegram from Gila Bend to Tucson on June 15. After withdrawing their much publicized witnesses, the prosecution continued to offer theories. However, they had nothing to present in court to establish McPherson's whereabouts anytime during the three weeks prior to her reappearance at Douglas, Arizona.[210][211][212]

A commentary published in an Ohio newspaper explored the situation. It did not help the prosecution's case in their claim that Ormiston and McPherson had been madly in love since Ormiston was absent from Los Angeles five months prior to the evangelist's disappearance. Also, Ormiston was being divorced by his wife, the pair could have gotten married. That she would choose to jeopardize her 2 million-dollar establishment that took great effort to create and undermine her career as a credible religious leader of 30,000 faithful followers to travel about the coast disguised in googles and a cap made no sense. If such an excursion were desired, there were easier and alternative methods she could have used.[213]

Other theories and innuendo were rampant on what actually occurred, and also without evidence to establish credibility: that she had run off with some other lover, had gone off to have an abortion, was taking time to heal from plastic surgery, or had staged a publicity stunt. Two-inch headlines called her a tart, a conspirator, and a home-wrecker.[78] She had once enjoyed only favorable press, nicknamed "miracle woman" [214] or "miracle worker" up until the time of the 1926 grand jury inquiry. Biographer Matthew Avery Sutton wrote McPherson learned that in a celebrity crazed-culture fueled by mass media, a leading lady could become a villainess in the blink of an eye.[215]

McPherson was heavily pressured to change her story; however, she never did and by demonstration, witness testimony and evidence, affirmed her story's plausibility.[216][217] Even in later years, when McPherson had a falling-out with her mother, Mildred Kennedy; and daughter, Roberta Star Semple; with unkind remarks traded through the press, the latter two always insisted her 1926 disappearance was the result of a kidnapping.

Alleged kidnappers

The McPherson party, apart from McPherson's testimony, claimed actual contact with the kidnappers through blind attorney-at-law Russell A. McKinley who was trusted by the kidnappers because he was blind. In May and again in June, two men, Miller and Wilson, aliases for "Steve" and the unnamed assailant of the McPherson complaint, allegedly approached him then made an offer to return Aimee Semple McPherson for $25,000. They told him a rubber mask was briefly used on McPherson when taking her and the drug was laced with one quarter grain (16 mg) of morphine insuring she was "doped" safely and quickly. They were given four questions passed to McKinley from Kennedy that only her daughter knew to prove the men actually had her. Mildred Kennedy also gave McKinley $1,000 to assist him in his work. A ransom note was relayed and given to the police who in disguise, visited a hotel lobby drop site as a precaution in case it was genuine. No results were forthcoming and the note dismissed as fraudulent. Another ransom note demanding $500,000 was sent to the Angelus Temple with two of the questions correctly answered. McPherson later recalled an incident from her captivity when two of the kidnappers returned annoyed from an errand at a hotel stating they recognized the detectives positioned there and left. She also said they asked her personal questions and once she realized what they were doing and refused to answer further. She thought as the $500,000 being asked for her return was way too much, the Temple did not have it. One of them then burned her with his cigar in an attempt to get the other two questions answered. They threatened to take a finger if their ransom note did not work. Some days later, McPherson escaped.

After McPherson's return to Los Angeles, McKinley promised to obtain information which would prove to the court kidnappers had indeed held her during the disappearance. Since McKinley had a good reputation,[218] Kennedy, McPherson, and Judge Carlos Hardy, continued to work with him. A car accident in August, though, claimed his life. McKinley's sudden death, Mildred Kennedy thought, was peculiar, occurring as it did just before he was ready to reveal some important piece of evidence. His death was considered a serious blow to McPherson's case. His secretary, Miss Bernice Morris, however, testified for the prosecution stating she did not believe there were any alleged kidnappers. She had respect for her late boss, Mr. McKinley, though on the stand was forced to consider either he was in on the plot to manufacture evidence or an unwitting dupe. The prosecution purported the McPherson party sent at least two persons posing as the kidnappers to fool McKinley and secure his testimony lending credibility to the kidnapping story. This theory, as one biographer, Nancy Barr Mavity pointed out, had serious issues since it introduced two extra persons into the scam increasing the likelihood of exposure.[219]