Ace Ventura: Pet Detective

| Ace Ventura: Pet Detective | |

|---|---|

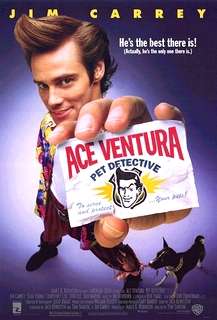

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tom Shadyac |

| Produced by | James G. Robinson |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Jack Bernstein |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Ira Newborn |

| Cinematography | Julio Macat |

| Edited by | Don Zimmerman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $107.2 million |

Ace Ventura: Pet Detective is a 1994 American comedy film starring Jim Carrey as Ace Ventura, an animal detective who is tasked with finding the abducted dolphin who is the mascot of the US football team Miami Dolphins. The film was directed by Tom Shadyac, who wrote the screenplay with Carrey and Jack Bernstein. The film co-stars Courteney Cox, Tone Loc, Sean Young and former Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino and features a cameo appearance from death metal band Cannibal Corpse.

The film was produced on a budget of $15 million. It received generally unfavorable reviews from critics. Carrey's performance led to the film having a cult following among male adolescents. At the worldwide box office, it grossed $107.2 million. In addition to launching Carrey's film career, it also spawned the sequel film Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls (1995), the animated TV series Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (three seasons, 1995–2000), and later, the direct-to-video spin-off Ace Ventura Jr.: Pet Detective (2009).

Plot

Ace Ventura is an eccentric, very unorthodox Miami-based private detective who specializes in retrieving tame or captive animals. He struggles to pay his rent, and is often mocked by the Miami Police Department, led by Lieutenant Lois Einhorn, who finds Ventura insufferable. Two weeks before the Miami Dolphins are to play in the Super Bowl, their mascot, a bottlenose dolphin named Snowflake, is kidnapped. Melissa Robinson, the Dolphins’ chief publicist, hires Ventura to find Snowflake.

Searching Snowflake's tank for clues, Ventura finds a rare triangle-cut orange amber stone, which he recognizes as a part of a 1984 AFC Championship ring. Ace suspects billionaire Ronald Camp may have stolen Snowflake, as he is known for collecting exotic animals through less-than-reputable means and sources. Ventura and Melissa sneak into Camp's party, where Ventura mistakes a shark for Snowflake and is nearly eaten. Camp apologizes and shakes Ventura's hand, revealing on one of his own fingers an amber stone identical to the one Ventura found. Ruling out Camp, Ventura concludes that a member of the 1984 Miami Dolphins line-up may have kidnapped Snowflake, and attempts to identify the culprit by their rings. However, he discovers all of the team members’ rings are intact.

Roger Podacter, the team's head of operations, mysteriously dies after falling from his apartment balcony. Einhorn declares it a suicide, but Ventura proves that it was murder. He comes across an old photograph of the football team, discovering an unfamiliar player named Ray Finkle, who was only added in during midseason. Finkle missed the field goal kick at the end of Super Bowl XIX, which cost the Dolphins the championship, ruining his career.

Visiting Finkle's parents, Ventura learns that Finkle fully blames Dan Marino for the end of his career due to Marino allegedly placing the ball incorrectly before the kick, and was subsequently committed to a mental hospital for homicidal tendencies. Marino is kidnapped himself shortly thereafter. Ventura visits Einhorn, pitching his theory that Finkle kidnapped both Marino and Snowflake in an act of revenge, since the dolphin has been given Finkle's old team number and a goal trick to boot. He also theorises that Finkle murdered Podacter. Einhorn compliments Ventura and kisses him.

Ventura and Melissa go to the mental hospital, the former posing as a potential patient, where he uncovers a newspaper article in Finkle's possessions about a missing hiker named Lois Einhorn. Ventura, with a clue from his dog, realizes that Einhorn is in fact Finkle: Finkle used the fact that the actual Einhorn was missing and presumed dead (with no body found), and took on her identity, had surgery to change his gender, and began a career with the Miami Police Department to eventually get revenge on Marino and the Dolphins. On Super Bowl Sunday, Ventura follows Einhorn to an abandoned yacht storage facility where she has Marino and Snowflake held hostage. Einhorn calls the police, framing Ventura for the kidnappings. Melissa and Ventura's friend, police officer Emilio, stage a hostage situation to get the police to listen to Ventura.

Ventura strips Einhorn of her clothes to expose her failure to completely change her sex, but fails until Marino points out a bulge in the back of his underwear, actually Finkle's unchanged privates hidden out of view. This confirms that Finkle murdered Podacter after the latter had discovered Finkle's secret. Einhorn is arrested by the police after attacking Ventura, and Finkle's ring is identified to have a missing stone. Marino and Snowflake are welcomed back during half-time at the Super Bowl in a match between the Dolphins and the Philadelphia Eagles. Ventura tries to retrieve a valuable albino pigeon, but it is scared off by the Eagles’ mascot Swoop, causing Ventura to attack him in retaliation.

Cast

- Jim Carrey as Ace Ventura

- Courteney Cox as Melissa Robinson

- Sean Young as Lt. Lois Einhorn / Ray Finkle

- Tone Loc as Emilio

- Dan Marino as Himself

- John Capodice as Sgt. Aguado

- Noble Willingham as Riddle

- Troy Evans as Roger Podacter

- Raynor Scheine as Woodstock

- Udo Kier as Ronald Camp

- Frank Adonis as Vinnie

- Tiny Ron as Roc

- David Margulies as Doctor

- Bill Zuckert as Mr. Finkle

- Judy Clayton as Martha Mertz

- Alice Drummond as Mrs. Finkle

- Rebecca Ferratti as Sexy Woman

- Mark Margolis as Mr. Shickadance, Ace's landlord

- Randall "Tex" Cobb as Gruff Man

- Cannibal Corpse as themselves

Production

The Chairman and CEO of Morgan Creek Productions, James G. Robinson, sought to produce a comedy that would have wide appeal. Gag writer Tom Shadyac pitched a rewrite of the script to Robinson and was hired as director for what was his directorial debut.[1] Filmmakers first approached Rick Moranis to play Ace Ventura, but Moranis declined the role. They then considered casting Judd Nelson or Alan Rickman, and they also considered changing Ace Ventura to be female and casting Whoopi Goldberg as the pet detective. Ultimately the producers noticed Jim Carrey's performance in the sketch comedy show In Living Color and cast him as Ace Ventura.[2]

Carrey helped rewrite the script, and filmmakers allowed him to improvise on set. Carrey said of his approach, "I knew this movie was going to either be something that people really went for, or it was going to ruin me completely. From the beginning of my involvement, I said that the character had to be rock 'n' roll. He had to be the .007 of pet detectives. I wanted to be unstoppably ridiculous, and they let me go wild." He said he sought comedic moments that would be unappealing to some, "I wanted to keep the action unreal and over the top. When it came time to do my reaction to kissing a man, I wanted it to be the biggest, most obnoxious, homophobic reaction ever recorded. It's so ridiculous it can't be taken seriously--even though it guarantees that somebody's going to be offended."[1]

The film was produced on a budget of $15 million.[3]

Release

Warner Bros. released Ace Ventura: Pet Detective in 1,750 theaters in the United States and Canada on February 4, 1994. The film grossed $12.1 million on its opening weekend, ranking first at the box office and outperforming other new releases My Father the Hero and I'll Do Anything.[3] For its second weekend, it grossed $9.7 million and ranked first at the box office again,[4] outperforming newcomers The Getaway, Blank Check, and My Girl 2.[3] Variety reported of Ace Ventura's second weekend in box office performance, "The goofball comedy defied dire predictions by trackers, slipping just 20% for a three-day average of $5,075 and $ 24.6 million in 10 days."[4] The Los Angeles Times reported, "Audiences are responding enthusiastically to Carrey's frenzied antics... The film... is especially a hit with the 10- to 20-year-old age group it was originally targeted for. Box-office grosses indicate that many fans are going back to see the film again."[1] It grossed a total of $72.2 million in the United States and Canada and a total of $35 million in other territories for a worldwide total of $107.2 million.[3] The film's US box office performance led Variety to label it a "sleeper hit".[5] On home video, Ace Ventura sold 4.2 million home videos in its first three weeks, which Los Angeles Times called "just as powerful a draw" as its theatrical run.[6]

Carrey also starred in The Mask and Dumb and Dumber later in the year. The three films had a total box office gross of $550 million, which ranked Carrey as the second highest-grossing box office star in 1994, behind Tom Hanks.[7]

The Hollywood Reporter said before Ace Ventura, Jim Carrey was "seen mainly as TV talent" and that with the film's success, it "firmly [established] him as a big-screen presence". The film's success also led Morgan Creek Productions to produce the 1995 sequel Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls with Carrey reprising his role.[8] Author Victoria Flanagan wrote that Carrey's performance "generated cult success for the film among adolescent male viewers".[9] NME wrote in retrospect that the film was a "cult 1990s comedy".[10]

Critical reception

The Los Angeles Times reported at the time, "Not many critics have been charmed by Ace Ventura's exploits, and several have charged that the film's humor is mean-spirited, needlessly raunchy and homophobic."[1] Ace Ventura: Pet Detective received "generally unfavorable" reviews from contemporary critics, according to review aggregator Metacritic, which assessed 14 reviews and categorized six as negative, five as positive, and three as mixed. It gave the film an overall score of 37 out of 100 based on 14 contemporary reviews.[11] The review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 46% based on 52 reviews assessed as positive or negative, with an average rating of 4.5/10.[12]

Roger Ebert, reviewing for the Chicago Sun-Times, said, "I found the movie a long, unfunny slog through an impenetrable plot." Ebert described the lead role, "Carrey plays Ace as if he's being clocked on an Energy-O-Meter, and paid by the calories expended. He's a hyper goon who likes to screw his mouth into strange shapes while playing variations on the language."[13] James Berardinelli said, "The comic momentum sputters long before the running time has elapsed." Berardinelli said of Carrey that he "uses his rubber features and goofy personae" that succeeds for a short time but after that, "Carrey's act gradually grows less humorous and more tiresome, and the laughter in the audience seems forced." The critic said the film has "its moments" of humor but considered there to be "a lot of dead screen time" in between.[14]

The New York Times film critic Stephen Holden said, "The comic actor Jim Carrey gives one the most hyperactive performances ever brought to the screen... Only a child could love Mr. Carrey's character, but that may be the point. The movie has the metabolism, logic and attention span of a peevish 6-year-old." He said of Ace Ventura's animals, "The few scenes of Ace communicating with his animals hint at an endearing wackiness that is abruptly undercut by the movie's ridiculous plot."[15]

The Washington Post's film critics Rita Kempley and Desson Howe reviewed the film positively.[16][17] Kempley said, "A riot from start to finish, Carrey's first feature comedy is as cheerfully bawdy as it is idiotically inventive." She added, "A spoof of detective movies, the story touches all the bases."[16] Howe said that the film "is a mindless stretch of nonsense" and highlighted multiple "Carreyisms along the way". Howe concluded, "There are some unfortunate elements that were unnecessary -- a big strain of homophobic jokes for one, profane and sexual situations that rule out the kiddie audience for another. But essentially, Ace is an unsophisticated opportunity to laugh at the mischief Carrey's body parts can get up to."[17]

Accolades

| Award | Ceremony | Result | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Comedy Award for Funniest Lead Actor in a Motion Picture | 1995 American Comedy Awards | Nominated | ||

| Blockbuster Entertainment Award for Favorite Male Newcomer, On Video | 1st Blockbuster Entertainment Awards | Won | ||

| Blockbuster Entertainment Award for Favorite Actor - Comedy, On Video | Won | |||

| Chicago Film Critics Association Most Promising Actor Award | Chicago Film Critics Association Awards 1995 | Nominated | Also nominated for The Mask | |

| Golden Raspberry Award for Worst New Star | 15th Golden Raspberry Awards | Nominated | Also nominated for Dumb and Dumber and The Mask | |

| London Film Critics' Circle Newcomer of the Year Award | 1995 London Film Critics' Circle Awards | Won | Also won for The Mask | |

| MTV Movie Award for Best Comedic Performance | 1994 MTV Movie Awards | Nominated | [18] | |

| Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Award for Favorite Movie Actor | 1995 Kids' Choice Awards | Won | Also won for The Mask |

Transgender portrayal

Since the film was released, there has been some discussion over the way in which it portrays transgender people. Alexandra Gonzenbach Perkins wrote in Representing Queer and Transgender Identity that mainstream representation of transgender identity at the turn of the 21st century was limited, observing, "The representations that did exist tended to pathologize transgender people as mentally unstable." Perkins said Ace Ventura along with The Crying Game depicted "transgender characters as murderous villains".[19] In the book Reclaiming Genders, in a chapter focusing on transgender identity, Gordene O. Mackenzie references Ace Ventura as an example of turn-of-the-century films that "illustrate the transphobia implicit in many popular US films". Mackenzie describes the scene in which Ace Ventura retches in the bathroom, following the revelation that the woman he had kissed is trans, as "one of the most memorable and blatantly transphobic/homophobic scenes".[20] In The New York Times in 2016, Farhad Manjoo also writes about this scene, "There was little culturally suspect then about playing gender identity for laughs. Instead, as in many fictional depictions of transgender people in that era, the scene’s prevailing emotion is of nose-holding disgust."[21]

An episode of the sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine in 2016 referenced the portrayal with character Jake Peralta saying of Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, "Classic film, one of my childhood favorites, and it only gets overtly transphobic at the very end, so, a win." Vulture's Allie Pape wrote, "Someone on the writing staff clearly rewatched Ace Ventura: Pet Detective and found it wanting by modern standards."[22]

Planned reboot

In October 2017, Morgan Creek Entertainment Group announced plans to reboot several films from its library, including Ace Ventura: Pet Detective. Its president David Robinson said Morgan Creek's plan was not to simply remake the film, but to do a follow-up in which Ace Ventura passes the mantle to a new character, such as a long-lost son or daughter.[23]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Crisafulli, Chuck (February 18, 1994). "It's Zany and Aces With Fans : Movies: 'Ace Ventura' with Jim Carrey has taken in $24.6 million, and is still going strong". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Mell, Eila. Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4766-0976-8.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- 1 2 Klady, Leonard (February 14, 1994). "Weather storms B.O.; 'Ace' detects success". Variety. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Alexander, Max (April 25, 1994). "Robinson to widen Morgan Creek flow". Variety. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Cerone, Daniel (July 18, 1994). "He's All Bent Out of Shape Over 'High Strung' Plans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Willis, Andrew (2004). Film Stars: Hollywood and Beyond. Manchester University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7190-5645-1.

- ↑ Galloway, Stephen (May 8, 2017). "Home on the Range". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Flanagan, Victoria (2013). "Transsexualism versus hegemonic masculinity in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective". Into the Closet: Cross-Dressing and the Gendered Body in Children's Literature and Film. Routledge. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-136-77728-8.

- ↑ Reilly, Nick (October 27, 2017). "'Ace Ventura: Pet Detective' is being considered for a reboot". NME. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (February 4, 1994). "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ↑ Berardinelli, James (1994). "Review: Ace Ventura". movie-reviews.colossus.net. Archived from the original on 25 August 2006.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (February 4, 1994). "Reviews/Film; On the Trail Of a Lost Fish". The New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- 1 2 Kempley, Rita (February 4, 1994). "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- 1 2 Howe, Desson (February 4, 1994). "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ↑ "1994 MTV Movie Awards". MTV. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008.

- ↑ Perkins, Alexander Gonzenbach (2017). Representing Queer and Transgender Identity: Fluid Bodies in the Hispanic Caribbean and Beyond. Bucknell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-61148-840-1.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Gordene O. (2016). "50 Billion Galaxies of Gender: Transgendering the Millennium". In Whittle, Stephen. Reclaiming Genders: Transsexual Grammars at the Fin de Siecle. Gender Studies: Bloomsbury Academic Collections. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4742-9283-2.

- ↑ Manjoo, Farhad (June 7, 2016). "In the Fight for Transgender Equality, Winning Hearts and Minds Online". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Pape, Allie (September 20, 2016). "Brooklyn Nine-Nine Season Premiere Recap: America's Sticky Butt". Vulture. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (October 26, 2017). "Morgan Creek Prods. Rebrands Itself, Plans TV & Film Reboots Of 'Young Guns', 'Ace Ventura,' 'Major League' & More". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ace Ventura: Pet Detective |