Rapide-Blanc Generating Station

| Rapide-Blanc Generating Station | |

|---|---|

Centrale hydroélectrique de Rapide-Blanc | |

Location of Rapide-Blanc Generating Station in Quebec | |

| Country | Canada |

| Location | La Tuque, Quebec |

| Coordinates | 47°47′48″N 72°58′24″W / 47.79661°N 72.97342°WCoordinates: 47°47′48″N 72°58′24″W / 47.79661°N 72.97342°W |

| Purpose | Power |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 1930 |

| Opening date | 1934 |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Height (foundation) | 45 m (148 ft) |

| Height (thalweg) | 32.92 m (108.0 ft) |

| Length | 268 m (879 ft) |

| Width (crest) | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Reservoir | |

| Total capacity | 466,000,000 m3 (378,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Surface area | 8,200 ha (20,000 acres) |

| Normal elevation | 279.8 m (918 ft) |

| Operator(s) | Hydro-Québec |

| Turbines | 6 x 34 MW Francis-type |

| Installed capacity | 204 MW |

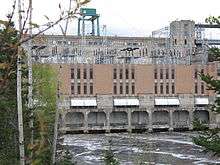

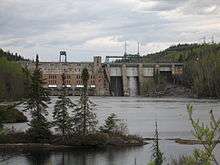

The Rapide-Blanc Generating Station is a hydroelectric plant, including a reservoir, a dam and hydroelectric plant, located on the Saint-Maurice River about sixty kilometres (37 mi) north of the city of La Tuque, in Quebec, in Canada. Built between 1930 and 1934 by Shawinigan Water & Power Company, it is the third built on this river from upstream plant. The plant is operated by Hydro-Québec since it was acquired from SWP in 1963, as part of the nationalisation of electric power companies in Quebec. The plant has a rated power of 204 megawatts (274,000 hp).

History

“Rapide-Blanc” (English: White Rapid) was deemed to be the most dangerous rapids of Saint-Maurice River. The Atikamekw preferred to use a series of 11 portages from Coucoucache to the mouth of the Vermillon River (La Tuque), upstream of La Trenche Generating Station, through the Coucoucache Creek.[1]

This hydroelectric dam was built on the site of the former "Rapide Blanc" whose designation exists at least since the mid-nineteenth century. After the construction of the dam, one of the oldest remaining rapids (below the dam), designated in French "Rapides de la Tête du Rapide Blanc" (Rapids of the Head of White Rapids). The name "Rapide-Blanc" (White Rapid) was also attributed to the rail stop located 12 km south of hameau.[2]

In 1928, the Shawinigan Water & Power Company acquired water rights on six of the seven sites that could be developed for power generation on the upper Saint-Maurice River, upstream of Grand-Mère. The company signed a long-term lease for using and developing the site during 75 years, to ensure the exclusivity of hydroelectric development on the whole basin. Under agreements with the Government of Quebec, the site of Rapide-Blanc, located 60 kilometres (37 mi) north of La Tuque is the first site to be developed. However, the Great Depression of 1930 forced the company to revise its growth forecast of electricity demand downwards.[3]

Under this agreement, the Shawinigan pledged to start construction of a plant with a minimum capacity of 75 MW (100,000 hp) in 1930, for a planned commissioning in 1933; the construction of a second unit was to follow in 1938.[3] But given the economic situation Shawinigan lakcluster sales between 1930 and mid-1932, the company requested some changes to the lease, including its extension from 75 to 95 years.[4] The Government agreed to change the terms, which delayed subsequent work.[3]

However, Shawinigan honors still the initial appointment; the construction of gravity dams of 268 m (879 ft) starts in 1930, as provided in the agreement signed two years before. The project was relatively complex and involved at the time including the movement of a section of the railway of Canadian National, which passed through the land to be flooded by the reservoir of the plant, along 50 km (31 mi).[3] Another consequence was the displacement of Indian Reserve of Coucoucache whose lands were flooded by the Reservoir Blanc. A new reserve 6 hectares (15 acres) was assigned by the government of Quebec on 16, replacing the old unit of 154 hectares (380 acres).[5] Shawinigan repaid the Canadian government for the loss of the previous reserve of 380 U.S. dollars on 1 January 1937.[5]

Despite the difficult economic environment, the directors of the company are confident of the project's profitability. According to the Annual Report 1932 Shawinigan, the unit cost of the first unit 120 MW (160,000 hp) power is estimated at less than US$100. The cost of production was lower after installing the last two generating units, the central being provided to accommodate six, with a combined capacity of 180 MW (240,000 hp). And as feared leaders of the company, the power of this new plant, whose construction was completed in 1934, was not required before the outbreak of the World War II in 1939.[3]

Plant expansion

The global conflict causes a dramatic increase in demand and the three main power grids of the time - those of Montreal Light, Heat and Power of Alcan and Shawinigan - put in establish new interconnections to optimize the production of electricity.[6] A fifth turbine generator was added in 1943.[7]

The war also forces the Shawinigan to question the safety of its installed works in Haute-Mauricie. The company is developing a service pigeons, responsible for rapidly communicate information about the most isolated in the event of air attack or sabotage of facilities and means of communication barriers. The Shawinigan Journal, business newspaper of Shawinigan Water & Power Company, reveals in his edition of 20 October in Quebec that company executives feared that the breaking of Gouin dam does not cause the destruction of downstream plants used to support the war effort.[8]

Thus we draw from 20 October of pigeons in Rapide-Blanc and Gouin, under the responsibility of employees of the company became pigeons amateurs. The best pigeons Shawinigan could make the trip between the two sites - 120 km (75 mi) apart as the crow flies - in 75 minutes, which represents an average speed of 100 km/h (62 mph).[8]

However, the new context of the post-war, with the creation of Hydro-Québec in 1944, confines Shawinigan territory more cramped as demand increases rapidly. To increase the installed capacity of the Saint-Maurice River, the Shawinigan ask the government for permission to proceed with the diversion of the headwaters of the Mégiscane River in Abitibi-Témiscamingue to the Gouin reservoir, whose mouth is located 164 km (102 mi) upstream from Rapide-Blanc.[9] Despite opposition from Hydro-Québec engineers, the private operator was allowed to proceed in September 1951, just days after Hydro-Québec was granted permission to build two large dams, Bersimis-1 and Bersimis-2, on the North Shore.[10]

After many hesitations, the Quebec government allows the Shawinigan partially divert the course of the Mégiscane River to increase the flow of the Saint-Maurice River. Along with this derivation, sixth turbine generator will be installed at La Tuque Generating Station, La Trenche and the Rapide-Blanc. The decision to proceed is taken into February and the new units will be commissioned in 1955. The cost of repairs, which have added 110 megawatts (150,000 hp) to the peak power of the three plants, totaled C$14 million[10]

The Village of Rapide-Blanc

From the 1930, the Shawinigan built a village to house the workers responsible for the operation of the plant, as well as their families. A series of red brick houses were erected on the east bank of the river at the dam. At the peak of construction of the La Trenche Generating Station, the total population of the village has never exceeded 65 families.[7]

Built on the model of English garden cities, the village had 42 single family homes, comfortable and heated by electricity. As in other remote Quebec communities Rapide-Blanc houses were owned by the operator of the plant, which leased the space to employees.[11]

The village also had an inn of 13 rooms, an Elementary School which offered instruction in French and English, both churches, a Catholic and a Protestant, a General Store, a filtration plant and medical clinic. Recreation facilities allow the practice of curling of ice hockey and skiing in winter, and tennis and softball in the summer. Before the construction of the La Trenche Generating Station, opened in 1950, the site was difficult to access, since workers were cut off from the road to La Tuque and to the rest of Quebec.[7]

Technological advances of 1960’s in telecommunications will, however, jeopardize the future of the village. The decision to control the plant at distance from La Tuque, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) downstream, is taken in 1969 by Hydro-Québec band the village was dismantled in 1974, to the dismay of workers who spent their career,[12] leaving up only 7 homes. Both are used by Hydro-Québec to hold meetings. The other five are available to Hydro-Québec employees can go to spend their holidays. The place is renowned for the quality of its fishing.[7] The brook trout, the gold, the Northern pike and trout are the most frequently caught species in[11] nearby lakes.

Automation

Rapide-Blanc Generating Station was transferred to Hydro-Québec when the government-owned corporation took control of private power companies in 1963. In January 1969, Hydro-Québec announces the automation of its plants in the Haut-Saint-Maurice. The draft 2.5 millions of Canadian dollar, led to the transfer of 71 employees assigned to sites Rapide-Blanc and La Trenche Generating Station, and closing of the village of Rapide-Blanc, where 54 families and 240 people lived. The company then invoked the increased accessibility to the site, the preference of employees for life in an urban environment and annual savings of $C450,000 to justify the abandonment of the village.[13]

The operation of the plant was automated by using a microwave network from the summer of 1971 and the plant is controlled from a station located in the downtown area of La Tuque. As of the early twenty-first century, there are only seven small houses that have been renovated and preserved.[14]

Since automation, hydro development is visited weekly by a team of a dozen workers responsible for maintenance of the plant and the three auxiliary dams in Manowan. In 2006, the downtime of 0.86% was the lowest in the Cascades sector of Hydro-Québec. Nevertheless, the system, which celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2009, requires some attention; work was carried out on a valve spillway in summer 2006.[15]

The power station installed on the roof of the plant was upgraded in 2007 to accommodate a new transmission line built at a cost of CA$104.5 million dollars.[16] Sixty kilometres (37 mi) long and consisting of guyed towers, a line 230 kV delivers electricity to new Chute-Allard and Rapides-des-Coeurs,[17] upstream, to the position of beeches in Shawinigan and the consumer markets of southern Quebec. Rapide-Blanc, an existing line goes south and shares a grip with the other lines which leave the other plants in the Haute-Mauricie and 450 kilovolt line to DC linking Radisson, near the central of James Bay to Nicolet on the south side of Saint Lawrence River, and thence to New England.

See also

See also

References

- ↑ Government of Quebec. "Coucoucache". Commission de toponymie du Québec. Commission de toponymie du Québec. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Names and places of Québec", the work of the Geographical Names Board published in 1994 and 1996 as an illustrated dictionary printed, and in that of a CD produced by Micro-Intel in 1997 from this dictionary.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dales 1957, p. 90.

- ↑ Bellavance 1994, p. 89.

- 1 2 Government of Canada. "Coucoucache" (PDF). Natural Resources Canada. Historique Foncier des Terres Indiennes au Québec. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ↑ Evenden, Matthew (2006). "La mobilisation des rivières et du fleuve pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale: Québec et l'hydroélectricité, 1939-1945". Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française (Historical review of French America (in French). 60 (1–2): 125–162. doi:10.7202/014597ar.

- 1 2 3 4 Rousseau, Dany (13 October 2001). "The James Bay 1930". Le Nouvelliste (in French). p. B6.

- 1 2 Kindersley, G. W. (November 1945). "Messengers of Shawinigan's Feathered Messengers". Shawinigan Journal. pp. 8–11.

- ↑ Hydro-Québec Production (August 2004). "2" (PDF). Rivière St-Maurice – Étude de rupture du barrage Gouin. Report RA-051-33 (in French). p. 12 5.

- 1 2 Bellavance 1994, p. 180-181.

- 1 2 "Au Rapide-Blanc: un village au nord du nord (At Rapide-Blanc: a village at the north of the north". Photo-Journal. 19 February 1969.

- ↑ Dionne, J. André (30 October 1974). "Carl Williams a vu naitre Rapide-Blanc et le verra aussi disparaitre (Carl Williams saw the birth of Rapide-Blanc and will also see it disappearing)" Check

|url=value (help). Echo. p. 22. - ↑ "automation continues his work. Closing the village of Rapide Blanc". Echo. La Tuque, Quebec. 29 January 1969. p. 3.

- ↑ "the road hydroelectric Haut-Saint-Maurice". Tourism Haut-Saint-Maurice. 2008. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ "Central Rapide-Blanc-Family Portrait". Hydro-Presse. Hydro-Québec. July–August 2006.

- ↑ Régie de l'énergie Quebec (28 February 2006). "Decision D-2006-36" (PDF).

- ↑ Newsletter #2 (November 2004). "Line 230 kV Chute-Allard-Rapide-Blanc" (PDF). Hydro-Québec TransÉnergie. p. 4. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2008-12-06.

Bibliography

- Bellavance, Claude (1994). Shawinigan Water and Power (1898-1963) : Formation et déclin d'un groupe industriel au Québec [Shawinigan Water and Power (1898-1963): Establishment and decline of a Quebec industrial group] (in French). Montréal: Boréal. ISBN 2-89052-586-4.

- Blanchet, Pascal (2006). Rapide Blanc (in French). Montréal: La Pastèque. ISBN 978-2-922585-43-8.

- Dales, John H. (1957), Hydroelectricity and Industrial Development Quebec 1898-1940, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

External links

- Le Rapide-Blanc - Site maintained by the village's former residents.

- Map of the Rapide-Blanc Generatiing station

- Rapide-Blanc Dam - Centre d'expertise hydrique du Québec