October Sky

| October Sky | |

|---|---|

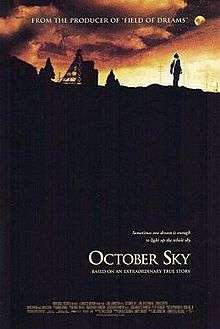

Theatrical release

poster | |

| Directed by | Joe Johnston |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | Lewis Colick |

| Based on |

October Sky by Homer Hickam |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Mark Isham |

| Cinematography | Fred Murphy |

| Edited by | Robert Dalva |

Production company |

Universal Studios |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million |

| Box office | $34.7 million |

October Sky is a 1999 American biographical drama film directed by Joe Johnston, starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Chris Cooper, Chris Owen, and Laura Dern. It is based on the true story of Homer H. Hickam, Jr., a coal miner's son who was inspired by the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957 to take up rocketry against his father's wishes and eventually became a NASA engineer.

"October Sky" is based on the lives of four young men who grew up in Coalwood, West Virginia.[1] Most of the film was shot in rural East Tennessee, including Oliver Springs, Harriman and Kingston in Morgan and Roane counties. The movie received a positive critical reception and is still celebrated in the regions of its setting and filming.

Title

October Sky is an anagram of Rocket Boys, the title of the 1998 book upon which the movie is based. It is also used in a period radio broadcast describing Sputnik 1 as it crossed the "October sky". Homer Hickam stated that "Universal Studios marketing people got involved and they just had to change the title because, according to their research, women over thirty would never see a movie titled Rocket Boys"[2] so Universal Pictures changed the title to be more inviting to a wider audience. The book was later re-released with the name in order to capitalize on interest in the movie.

Plot

In October 1957, news of the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik 1 reaches the town of Coalwood, where most people work in the coal mines. As the townspeople gather outside on the night of the broadcast, they see the satellite orbit across the sky. Homer H. Hickam Jr., filled with awe, sets out to build his own rockets to hopefully get out of Coalwood. His family and classmates' do not respond kindly, especially his father John (the mine superintendent), who wants Homer to join him in the mines.

Despite this, Homer eventually teams up with math geek Quentin Wilson, who also has an interest in rocket engineering; with the support of his friends, Roy Lee Cooke and Sherman O'Dell, and their science teacher, Miss Frieda J. Riley — known as Miss Riley, the four construct small rockets. While their first launches are failures, they experiment with new fuels and designs and eventually succeed. The local paper runs a story about them after a few of their launches. Nevertheless, they are accused of starting a forest fire with an astray rocket and are arrested. After John picks up Homer, Roy Lee is beaten up by his abusive stepfather, Vernon. John intervenes and rescues Roy Lee, warning Vernon that he will protect Roy Lee as Roy Lee's late father would have.

The four abandon rocketry and destroy their launch site. After a mine disaster, John is injured while rescuing other men. One of the miners, Ike Bykovsky, a machine shop worker who let Homer use the shop for rocketry and transferred for better pay, is killed. Homer drops out of high school and works the mine to provide for the family while his father recovers.

Later, Homer is inspired to look at a rocket science book Miss Riley has given him, learning how to calculate the trajectory of a rocket. Using this, he and Quentin locate the rocket while proving that it could not have caused the fire, as it was unable to travel that far. The boys present their findings to Miss Riley and the school principal, Mr. Turner, who follows up and identifies the catalyst as a flare from a nearby airfield. Homer returns to school by special invitation; the boys return to rocketry and win the school science fair. This wins them the opportunity to participate in the National Science Fair in Indianapolis. As only one of them can go there, they elect Homer.

Meanwhile, the workers' union goes on strike against John. That night, when the family eats dinner, Vernon shoots into the kitchen and misses John. Homer and Jim express their concern to their father, but John dismisses their fears. Fed up, Homer confronts his father, and a heated argument ensues. The mines are set to close down and there is nothing but trouble and no future for Homer in the mines. He resents his father's pressures to follow in the mine work and storms out of the house, vowing to never return.

At the fair, Homer's display is received very well. After a scheduled few days show, the prizes are to be awarded, and Homer enjoys top popularity and some sightseeing. Overnight, someone steals his machined rocket part model – the de Laval nozzle – as well as his autographed picture of Dr. Wernher von Braun. Homer makes an urgent phone call home for help. His mother, Elsie, implores John to end the ongoing strike so that Mr. Bolden, Bykovsky's replacement, can use the mine's machine shop to build a replacement nozzle. John relents when Elsie, fed up with his lack of support for their son, threatens to leave him. With the town's support, Homer wins the top prize and is bombarded with scholarship offers from colleges. He is also congratulated by his inspiration, von Braun, but does not realize the engineer's identity until he has gone.

Homer returns to Coalwood as a hero and visits Miss Riley, who is dying of Hodgkin's disease. A launch of their largest rocket yet (the Miss Riley) is the last scene of the film. John, who never attended any of the launchings, attends and is given the honor of pushing the launch button. The Miss Riley reaches an altitude of 30,000 feet (9,100 m) — higher than the summit of Mount Everest. As the crowd (and the rest of the town) looks up to the skies, John slowly puts his hand on Homer's shoulder and smiles, showing Homer that he is proud of him.

At the end of the film, a series of vignettes reveals the true outcomes of the main characters' lives.

Cast

- Jake Gyllenhaal as Homer Hickam

- Chris Cooper as John Hickam

- Chris Owen as Quentin Wilson

- Laura Dern as Miss Freida J. Riley

- William Lee Scott as Roy Lee Cooke

- Chad Lindberg as Sherman O'Dell

- Natalie Canerday as Elsie Hickam

- Jonathan Freeman as Leon Bolden

- Chris Ellis as Principal Turner

- Elya Baskin as Ike Bykovsky

- O. Winston Link as Railroad engineer

- Andy Stahl as Jack Palmer

Production

Filming began on February 23, 1998, almost a year before the movie's release. Although the film takes place in West Virginia, Tennessee was the location of choice for filming in part because of the weather and area terrain. Film crews reconstructed the sites to look like the 1957 mining town setting the movie demanded. The weather of east Tennessee gave the filmmakers trouble and delayed production of the film. Cast and Crew recalled the major weather shifts and tornadoes in the area during the filming months but Joe Johnston claims, "ultimately, the movie looks great because of it. It gave the film a much more interesting and varied look."[3][4] The crews also recreated a mine for the underground scenes. Director Joe Johnston expressed that he felt that the looks of the mine in the film gave it an evil look, like the mine was the villain in the film. And felt it ironic because that is what gave the town its nourishment. More than 2000 extras were used in the movie. A small switching yard allowed the filmmakers and actors to film the scenes with the boys on the rail road and gave them freedom to do as they pleased, even tear apart tracks. The train used in the scene was the former Southern Railway 4501 relettered as Norfolk and Western 4501. Filming concluded on April 30, 1998.[3]

The film's star, Jake Gyllenhaal, was 17-years-old during filming, the same as Homer Hickam's character. In an interview in 2014, Natalie Canerday recalled that Gyllenhaal was tutored on set because he was still in school and taking advanced classes.[4]

Release

Box office

October Sky opened on February 19, 1999 in 1,495 theaters and had an opening weekend gross of $5,905,250. At its widest theater release, 1,702 theaters were showing the movie. The movie has had a total lifetime gross of $34,675,800 worldwide.[5]

Critical reception

The film received critical acclaim from film critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 90% out of 72 critics gave the film a positive review, with a rating average of 7.6/10. The critic's consensus states: "Rich in sweet sincerity, intelligence, and good old-fashioned inspirational drama, October Sky is a coming-of-age story with a heart to match its Hollywood craftsmanship."[6] Metacritic gave the film a 71 rating with these being dubbed "Generally Favorable Reviews" based on 23 professional critic reviews of the movie.[7]

Many critics tend to commend the movie for its values, family, and inspirational aspects. A lot of reviews focus on the main character's relationship with his father and on the actors' performances. Roger Ebert recognized that the film "doesn't simplify the father into a bad guy or a tyrant. He understandably wants his son to follow in his footsteps, and one of the best elements of the movie is in breaking free, he is respecting his father. This movie has deep values."[8][7]

James Wall of The Christian Century describes the film's concentration on the father-son relationship as "at times painful to watch. There are no winners or losers when sons go their separate ways. October Sky does not illustrate good parenting; rather, it evokes the realization that since parents have only a limited vision of how to shape their children's future, the job requires a huge amount of love and a lot of divine assistance."[9] However, some reviews, such as one from Entertainment Weekly and TV Guide, claim that the movie's highlight was the acting of Jake Gyllenhaal and Chris Cooper.[10][11][12]

Accolades

October Sky won three awards, including: OCIC Award for Joe Johnston at the Ajijic International Film Festival 1999, the Critics' Choice Movie Awards for Best Family Film from the Broadcast Film Critics Association in 2000, and a Humanitas Prize 1999 for Featured Film Category.[13]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[14]

Differences between the film and book

Although the movie was praised for its portrayal of 1950s Appalachia, it has several major and minor differences from the book on which it is based.

- Homer Hickam is the main character's name; however, in the book and in real life he was nicknamed "Sonny".[15][16]

- Homer Hickam Jr's father was not named John. This was changed in an effort to keep the audience from being confused.[16][17]

- There were actually six "rocket boys" instead of the four in the movie. Some of the movie's representations of the characters are combinations of the real life boys. Their names were: Homer Hickam Jr., Quentin Wilson, Jimmy O'Dell Carroll, Roy Lee Cooke, Billy Rose and Sherman Siers.[15][16]

- The Rocket Boys did not steal railroad parts as they did in the film; however, they did attempt to grab a cast iron pipe under the tracks and, according to Homer's website, this almost got him killed[15]

- Homer never dropped out of school to work in the town's mine. He did, however, work in the mine the following summer, as described in Hickam's book Sky of Stone[15]

- Homer never met Wernher von Braun- he left the room and von Braun was gone when he came back[16]

Cultural impact

There are two annual festivals in honor of the Rocket Boys and the movie that are held. One is held in West Virginia where the real life events that the book and film took place, and the other is in Tennessee where the movie was actually shot. The "Rocket Boys" often visit the festival in West Virginia on a regular basis, and it is also called the "Rocket Boys Festival", while the festival in Tennessee focuses more on the filming locations being the relevance to the movie. The Tennessee festival's site claims that the festival is "a celebration of our heritage."[18][19]

Jeff Bezos, the billionaire founder of Amazon, saw a screening of October Sky in 1999. In a subsequent conversation with the science fiction writer Neal Stephenson, Bezos commented that he had always wanted to start a space company. Stephenson urged him to do so. Bezos then started the private aerospace manufacturing and services company Blue Origin, and Stephenson became one of the company's early employees.[20][21]

References

- ↑ "Coalwood, West Virginia Web Site". www.coalwoodwestvirginia.com. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ Homer Hickam official Web site - October Sky/Rocket Boys, The Keeper's Son Archived 2008-02-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "About the Filming". Coalwood West Virginia. NMT Web Designs, LLC. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- 1 2 Kazek, Kelly. "'October Sky' actress Natalie Canerday on Jake Gyllenhaal, Chris Cooper, film's legacy 15 years after debut". al.com. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "October Sky". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ October Sky. Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Critic Reviews for October Sky". Metacritic. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "October Sky Review". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ Wall, J.M. (1999). "Fathers and Sons". The Cristian Century. 116 (10): 331.

- ↑ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (March 5, 1999). "Rocket Booster". Entertainment Weekly (475).

- ↑ McDonagh, Maitland. "October Sky Review". TV Guide. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Critic Reviews for October Sky". Metacritic. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "October Sky Awards". imdb.com.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- 1 2 3 4 "Movies Rocket Boys". homerhickam.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-10. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Kazek, Kelly. "Real vs. Reel: Author Homer Hickam talks differences in 'Rocket Boys' and film 'October Sky'". al.com. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Bonvillian, Crystal. "'October Sky' does good job of telling Homer Hickam Jr.'s remarkable story". al.com. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "October Sky Festival". October Sky Festival. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ "October Sky Festival". Coalwood West Virginia. NMT Web Designs, LLC.

- ↑ Davenport, Christian (2018). The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos. PublicAffairs, an imprint owned by Hachette Book Group. ISBN 9781610398299.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (March 26, 2018). "Reviews: Rocket Billionaires and The Space Barons". The Space Review online magazine.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: October Sky |