History of Cincinnati

Cincinnati was founded in late December 1788 by Mathias Denman, Colonel Robert Patterson and Israel Ludlow. The original surveyor, John Filson, named it "Losantiville",[1] from four terms, each of different language, before his death in October 1788.[2] It means "The city opposite the mouth of the river"; "ville" is French for "city", "anti" is Greek for "opposite", "os" is Latin for "mouth", and "L" was all that was included of "Licking River".

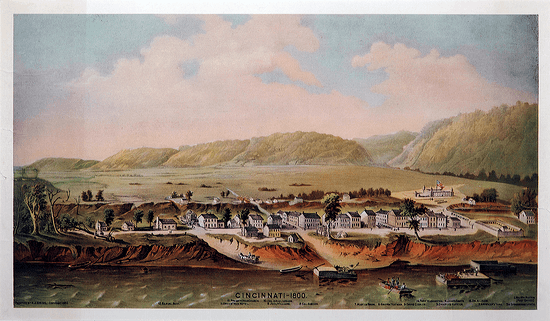

Early history

Cincinnati began as three settlements between the Little Miami and Great Miami rivers on the north shore of the Ohio River. Columbia was on the Little Miami, North Bend on the Great Miami. Losantiville, the central settlement, was opposite the mouth of the Licking River.

In 1789 Fort Washington was built to protect the settlements in the Northwest Territory. The post was constructed under the direction of General Josiah Harmar and was named in honor of President George Washington.[3]

On January 4, 1790, Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory, changed the name of the settlement to "Cincinnati" in honor of the Society of the Cincinnati, of which he was president,[4] possibly at the suggestion of the surveyor Israel Ludlow.[5] The society gets its name from Cincinnatus, the Roman general and dictator, who saved the city of Rome from destruction and then quietly retired to his farm. The society honored the ideal of return to civilian life by military officers following the Revolution rather than imposing military rule. To this day, Cincinnati in particular, and Ohio in general, is home to a disproportionately large number of descendants of Revolutionary War soldiers who were granted lands in the state. Cincinnati's connection with Rome still exists today through its nickname of "The City of Seven Hills"[6] (a phrase commonly associated with Rome) and the town twinning program of Sister Cities International.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, a series of six artillery batteries were built along the Ohio River to protect the city. Only one, Battery Hooper, now the James A. Ramage Civil War Museum in Fort Wright, Kentucky, is open to the public.

During the American Civil War, Cincinnati played a key role as a major source of supplies and troops for the Union Army. It also served as the headquarters for much of the war for the Department of the Ohio, which was charged with the defense of the region, as well as directing the army's offensive into Kentucky and Tennessee. Due to Cincinnati's commerce with slave states and history of settlement by southerners from eastern states, many people in the area were "Southern sympathizers". Some participated in the Copperhead movement in Ohio.[7] In July 1863, the Union Army instituted martial law in Cincinnati due to the imminent danger posed by the Confederate Morgan's Raiders. Bringing the war to the North, they attacked several outlying villages, such as Cheviot and Montgomery.[8][9]

'Porkopolis' and other nicknames

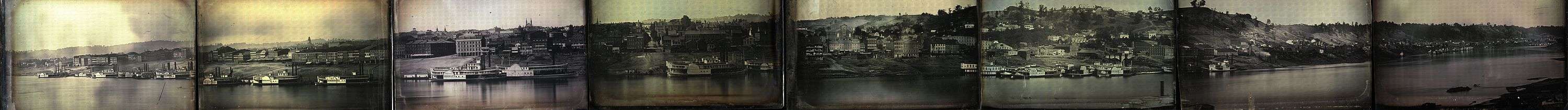

Cincinnati was chartered as a town on January 1, 1802.[10][11] It was chartered as a city by an act of the General Assembly that passed February 5, 1819, and took effect on March 1 of that year.[12] The introduction of steam navigation on the Ohio River in 1811 and the completion of the Miami and Erie Canal helped the city grow to 115,000 citizens by 1850. The nickname Porkopolis was coined around 1835, when Cincinnati was the country's chief hog packing center, and herds of pigs traveled the streets. Called the "Queen of the West" by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (although this nickname was first used by a local newspaper in 1819), Cincinnati was an important stop on the Underground Railroad, which helped slaves escape from the South.

Cincinnati also is known as the "City of Seven Hills". The seven hills are fully described in the June, 1853 edition of the West American Review, "Article III--Cincinnati: Its Relations to the West and South". The hills form a crescent from the east bank of the Ohio River to the west bank: Mount Adams, Walnut Hills, Mount Auburn, Vine Street Hill, College Hill, Fairmount, and Mount Harrison.

Cincinnati was the site of many historical beginnings. In 1850 it was the first city in the United States to establish a Jewish Hospital. It is where America's first municipal fire department, the Cincinnati Fire Department, was established in 1853. Established in 1867, the Cincinnati Red Stockings (a.k.a. the Cincinnati Reds) became the world's first professional (all paid, no amateurs) baseball team in 1869. In 1935, major league baseball's first night game was played at Crosley Field. Cincinnati was the first municipality to build and own a major railroad in 1880. In 1902, the world's first re-inforced concrete skyscraper was built, the Ingalls Building.

In 1888, Cincinnati German Protestants community started a "sick house" ("Krankenhaus") staffed by deaconesses. It evolved into the city's first general hospital, and included nurses' training school. It was renamed Deaconess Hospital in 1917.[13]

"The Sons of Daniel Boone", a forerunner to the Boy Scouts of America, began in Cincinnati in 1905. Because of the city's rich German heritage, the pre-prohibition era allowed Cincinnati to become a national forerunner in the brewing industry.[14] During experimentation for six years (until 1939), Cincinnati's AM radio station, WLW was the first to broadcast at 500,000 watts.[15] In 1943, King Records (and its subsidiary, Queen Records) was founded, and went on to record early music by artists who became highly successful and influential in Country, R&B, and Rock. WCET-TV was the first licensed public television station, established in 1954.[16] Cincinnati is home to radio's WEBN 102.7 FM, the longest-running album-oriented rock station in the United States, first airing in 1967. In 1976, the Cincinnati Stock Exchange became the nation's first all-electronic trading market.

Police and Fire Services

The first sheriff, John Brown, was appointed September 2, 1788. The Ohio Act in 1802 provided for Cincinnati to have a village marshall and James Smith was appointed; the following year the town started a "night watch". In 1819, when Cincinnati was incorporated as a city, the first city marshal, William Ruffin, was appointed. In May 1828, the police force consisted of one captain, one assistant, and five patrolmen. By 1850, the city authorized positions for a police chief and six lieutenants, but it was 1853 before the first police chief, Jacob Keifer, was appointed and he was dismissed after 3 weeks.

Cincinnati accompanied its growth by paying men to act as its fire department in 1853, making the first full-time paid fire department in the United States. It was the first in the world to use steam fire engines.[17]

Sports

The Cincinnati Red Stockings, a baseball team whose name and heritage-inspired today's Cincinnati Reds, began their career in the 19th century as well. In 1868, meetings were held at the law offices of Tilden, Sherman, and Moulton to make Cincinnati's baseball team a professional one; it became the first regular professional team in the country in 1869. In its first year, the team won 57 games and tied one, giving it the best winning record of any professional baseball team in history.[18]

In 1970 and 1975, the city completed Riverfront Stadium and Riverfront Coliseum, respectively, as the Cincinnati Reds baseball team emerged as one of the dominant teams of the decade. In fact, the Big Red Machine of 1975 and 1976 is considered by many to be one of the best baseball teams to ever play the game. Three key players on the team (Johnny Bench, Tony Pérez, and Joe Morgan), as well as manager Sparky Anderson, were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, while a fourth, Pete Rose, still holds the title for the most hits (4,256), singles (3,215), games played (3,562), games played in which his team won (1,971), at-bats (14,053) and outs (10,328) in baseball history.

The Cincinnati Bengals football team of the NFL was founded in 1968 by legendary coach Paul Brown. The team appeared in the 1981 and 1988 Super Bowls.

FC Cincinnati, Cincinnati's professional soccer team of the United Soccer League, was founded in 2015. While currently in a division II league, the club has received international recognition for its consistent record-breaking attendance numbers and historic 2017 Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup run. The team has been granted a spot in Major League Soccer for their 2019 expansion.[19]

Commerce

In 1879, Procter & Gamble, one of Cincinnati's major soap manufacturers, began marketing Ivory Soap. It was marketed as "light enough to float." After a fire at the first factory, Procter & Gamble moved to a new factory on the Mill Creek and renewed soap production. The area became known as Ivorydale.[20]

Additionally, Cincinnati was the largest manufacturer of carriages in the world. Flint Michigan was Cincinnati's closest rival, but was far behind in the extent of the industry. Around the turn of the century, Cincinnati manufactured approximately 140,000 four wheeled vehicles annually. There were numerous ancillary businesses. In example the Thomas H. Corcoran Co. of Norwood Ohio produced 50,000 pair of carriage lamps annually before they transitioned into auto lamps in 1905.

Disasters

On December 3, 1979 11 persons were killed in a crowd crush at the entrance of Riverfront Coliseum for a rock concert by the British band The Who.

Cincinnati has experienced multiple floods in its history. The largest being the Ohio River flood of 1937 where Cincinnati measured flood waters at 80 feet.[21]

Being in the Midwest, Cincinnati has also experienced several violent tornadoes. Of the 1974 Super Outbreak tornadoes, a F5 crossed the Ohio River from northern Kentucky into Sayler Park, the westernmost portion of the city along the Ohio River. The tornado then continued north into the suburbs of Mack, Bridgetown and Dent before weakening. The parent thunderstorm went on to produce another violet F4 that touched down in Elmwood Place and Arlington Heights before leaving the city limits and tracking toward Mason, Ohio. Three people lost their lives, while over another 100 were injured in both of these tornadoes. In the early morning hours of 9 April 1999, another violent tornado grazed the Cincinnati Metro, in the suburb of Blue Ash. It was rated an F4 killing 4 residents.[22]

Modern urban development

After World War II, Cincinnati unveiled a master plan for urban renewal that resulted in modernization of the inner city. Like other older industrial cities, Cincinnati suffered from economic restructuring and loss of jobs following deindustrialization in the mid-century.

The City of Cincinnati and Hamilton County are currently developing the Banks - an urban neighborhood along the city's riverfront including restaurants, clubs, offices, and homes with skyline views. Adjacent is Smale Riverfront Park, a new "front porch" to Ohio.

A 3.6-mile streetcar line running through downtown and Over the Rhine was completed in 2015 and called the Cincinnati Bell Connector.

Race relations

Cincinnati was a border town between slave states and free states in the Union during the Civil War. There have been many incidents of race-based violence before and after the Civil War with the most notable and most recent one being the 2001 Cincinnati Riots.

Situated across the Ohio River from the border state of Kentucky, which allowed slavery, Ohio was a major focal point for commerce and transportation with the South. Although slavery was not permitted before the Civil War, some in the city were not accepting of blacks. Many residents had personal and business ties to slaveholders across the river. Other whites competed for jobs with the free blacks who had migrated there from Virginia and other southern states to make new starts in the Northwest. Tensions broke out in riots and racial purges. Confrontations occurred between abolitionists and slaveholders over runaway slaves and free blacks kidnapped into bondage.

The Cincinnati Riots of 1829 broke out in July and August 1829 as whites attacked blacks in the city. Many of the latter had come from the South to establish a community with more freedom. Some 1200 blacks left the city as a result of rioting and resettled in Canada.[23] Blacks in other areas tried to raise money to help people who wanted to relocate to Canada. The riot was a topic of discussion in 1830 among representatives of seven states at the first Negro Convention, led by Bishop Richard Allen and held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

As the anti-slavery movement grew, there were more riots in 1836, when whites attacked a press run by James Birney, who had started publishing the anti-slavery weekly The Philanthropist. The mob grew to 700 and also attacked black neighborhoods and people.[24] Another riot occurred in 1841.[23]

Underground Railroad

Cincinnati was an important stop for the Underground Railroad in pre-Civil War times. It bordered a slave state, Kentucky, and is often mentioned as a destination for many people escaping the bonds of slavery. There are many harrowing stories involving abolitionists, runaways, slave traders and free men.

Allen Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in 1824 as the first Black church in Ohio. It was an important stop on the Underground Railroad for many years. It seeded many other congregations in the city, across the state, and throughout the Midwest.

Lane Theological Seminary was established in the Walnut Hills section of Cincinnati in 1829 to educate Presbyterian ministers. Prominent New England pastor Lyman Beecher moved his family (Harriet and son Henry) from Boston to Cincinnati to become the first President of the Seminary in 1832.

Lane Seminary is known primarily for the "debates" held there in 1834 that influenced the nation's thinking about slavery. Several of those involved went on to play an important role in the abolitionist movement and the buildup to the American Civil War. Abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin, first published on March 20, 1852. The book was the best-selling novel of the 19th century (and the second best-selling book of the century after the Bible)[25] and is credited with helping to fuel the abolitionist cause in the United States prior to the American Civil War. In the first year after it was published, 300,000 copies of the book were sold. In his 1985 book Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, Thomas Gossett observed that "in 1872 a biographer of Horace Greeley would argue that the chief force in developing support for the Republican Party in the 1850s had been Uncle Tom's Cabin." The Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati is located at 2950 Gilbert Avenue, and it is open to the public.

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, located in downtown Cincinnati on the banks of the Ohio River, largely focuses on the history of slavery in the U.S., but has an underlying mission of promoting freedom in a contemporary fashion for the world. Its grand opening ceremony in 2002 was a gala event involving many national stars, musical acts, fireworks, and a visit from the current First Lady of the United States. It is physically located between Great American Ballpark and Paul Brown Stadium, which were both built and opened shortly before the Freedom Center was opened.

Gallery

Women made 37mm antitank shells for the war in 1942 at Aluminum Industries, Inc. in Cincinnati.

Women made 37mm antitank shells for the war in 1942 at Aluminum Industries, Inc. in Cincinnati.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Filson Historical Society". The Filson Historical Society. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ "History of Cincinnati, Ohio". Archived from the original on 2014-06-28.

- ↑ "Fort Washington - Ohio History Central". www.ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ Suess, Jeff (December 28, 2013). "Cincinnati's beginning: The origin of the settlement that became this city". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Gannett Company. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

On Jan. 2, 1790, Gen. Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, came to inspect Fort Washington. He was pleased with the fort but disliked the name Losantiville. Two days later, he changed it to Cincinnati, after the Society of the Cincinnati, a military society for officers in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

- ↑ Teetor, Henry Benton (May–October 1885). "Israel Ludlow and the naming of Cincinnati". Magazine of Western History. Cleveland. 2: 251–257.

The fair and reasonable presumption is that after consultation (certainly with Ludlow, the surveyor of the town, the proprietor of a two-thirds' interest in his own right, and as agent of Denman), St. Clair adopted the name suggested by Ludlow—a name which, as may seen from the following testimony, was not only mentioned for more than a year prior to the coming of St. Clair, but was selected and adopted by Denman, Patterson and Ludlow in the winter of 1788–9, and was inscribed upon the plat made by Ludlow to take the place of the one first made by Filson, which was destroyed in a personal altercation between Colonel Ludlow and Joel Williams.

- ↑ "Cincinnati.com". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ "Copperheads". Ohio History Central. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Historical Society. July 1, 2005. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ↑ "Cheviot City Services" (PDF). City of Cheviot. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Lesson Plans: Morgan's Raid in Ohio" (PDF). Ohio Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2005. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Greve 1904, p. 27: "The act to incorporate the town of Cincinnati was passed at the first session of the second General Assembly held at Chillicothe and approved by Governor St. Clair on January 1, 1802."

- ↑ "Map". www.libraries.uc.edu.

- ↑ Greve 1904, pp. 507–508: "This act was passed February 5, 1819, and by virtue of a curative act passed three days later took effect on March 1, of the same year."

- ↑ Ellen Corwin Cangi, "Krankenhaus, Culture and Community: The Deaconess Hospital of Cincinnati, Ohio, 1888-1920," Queen City Heritage (1990) 48#2 pp 3-14

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-04-30. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ "For a Brief Time in the 1930s, Radio Station WLW in Ohio Became America's One and Only "Super Station"". NEH. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ "Fire Department History". City of Cincinnati. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ↑ Robert Vexler. Cincinnati: A Chronological & Documentary History.

- ↑ "FC Cincinnati's MLS berth imminent; Club to join in 2019". Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ Writers' Program, Cincinnati: A Guide to the Queen City and its Neighbors, Washington, D.C.: Works Project Administration

- ↑ "Flood of 1937 - Flood of 1997 - The Enquirer". www.enquirer.com. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ O'Quinn, Cyndee (16 November 2011). "10th Anniversary Of Blue Ash Tornado". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- 1 2 Carter G. Woodson, Charles Harris Wesley, The Negro in Our History, Associated Publishers, 1922, p. 140 (digitized from original at University of Michigan Library), accessed 13 Jan 2009

- ↑ "The Pro-Slavery Riot in Cincinnati", Abolitionism 1830-1850, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, University of Virginia, 1998-2007, accessed 14 Jan 2009

- ↑ http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-uncletomscabin/intro.html Introduction to Uncle Tom's Cabin Study Guide

Sources

- Cincinnati Firsts. Greater Cincinnati Convention and Visitors Bureau.

- Evolution of the National Weather Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Further reading

- Aaron, Daniel. Cincinnati, Queen City of the West: 1819-1838 (1992), 531pp.

- Cowan, Aaron. A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism and Urban Revitalization in the Postwar Rustbelt (2016) compares Cincinnati, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore in the wake of deindustrialization.

- Greve, Charles Theodore (1904). Centennial History of Cincinnati and Representative Citizens. 1. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- Miller, Zane. Boss Cox's Cincinnati: Urban Politics in the Progressive Era (2000) excerpt and text search

- Wade, Richard C. "The Negro in Cincinnati, 1800-1830," Journal of Negro History (1954) 39#1 pp. 43–57 in JSTOR

- Wade, Richard C. The urban frontier: the rise of western cities, 1790-1830 (1959)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Cincinnati, Ohio. |

.png)