Race and the War on Drugs

The War on Drugs is a term for the actions taken and legislation enacted by the United States government, intended to reduce or eliminate the production, distribution, and use of illicit drugs. The War on Drugs began during the Nixon Administration,[1] with the goal of reducing the supply of and demand for illegal drugs, though an ulterior, racial motivation has been proposed.[2] The War on Drugs has led to controversial legislation and policies, including mandatory minimum penalties and stop-and-frisk searches, which have been suggested to be carried out disproportionately against minorities.[3][4] The effects of the War on Drugs are contentious, with some suggesting that it has created racial disparities in arrests, prosecutions, imprisonment and rehabilitation.[5][6] Others have criticized the methodology and conclusions of such studies.[7] In addition to enforcement disparities, some claim that the collateral effects of the War on Drugs have established forms of structural violence, especially for minority communities.[8][9]

Motivation for the War on Drugs

The War on Drugs was declared by U.S. President Richard M. Nixon during a Special Message to Congress delivered on June 17, 1971, in response to increasing rates of death due to narcotics.[1] During this announcement, Nixon distinguished between fighting the war on two fronts—the supply front and the demand front. To address the "supply" front, Nixon requested funding to train narcotics officers internationally, and proposed various legislation with the intent of disrupting illegal drug manufacturers. The "demand" front referred to enforcement and rehabilitation. To that end, Nixon proposed the creation of the Special Action Office of Drug Abuse Prevention, with the goal of coordinating various agencies in addressing demand for illegal drugs. He also requested an additional $105 million for treatment and rehabilitation programs, and additional funding to increase the size and technological capability of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs.[1]

Alternative motivation

A former Nixon aide has suggested that the War on Drugs was racially and politically motivated.[2]

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I'm saying? We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

— John D. Ehrlichman, former Nixon aide, interview with Dan Baum

However, because he may have been disillusioned with the Nixon administration following the Watergate scandal, the validity of Ehrlichman's claim is disputed.[10][11]

Controversial policies

A number of policies introduced during the War on Drugs have been singled out as particularly racially disproportionate.

Mandatory minimums

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 established a 100:1 sentencing disparity for the possession of crack vs. powder cocaine. Whereas possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine triggered a 5-year mandatory minimum sentence, possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine triggered the same mandatory minimum penalty.[12] In addition, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 established a 1-year mandatory minimum penalty for simple possession of crack cocaine, making crack cocaine the only controlled substance for which a first possession offense triggered a mandatory minimum penalty.[3]

A 1992 study found that, as a result of mandatory minimum sentencing, blacks and Hispanics received more severe sentences than their white counterparts from 1984 through 1990.[13]

In 1995, the United States Sentencing Commission delivered a report to Congress concluding that, because 80% of crack offenders were black, the 100:1 disparity disproportionately affected minorities. The Commission recommended that the crack-to-powder sentencing ratio be amended, and that other sentencing guidelines be re-evaluated.[3] These recommendations were rejected by Congress.[14] By contrast, certain authors have pointed out that the Congressional Black Caucus backed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, implying that that law could not be racist.[15][16]

In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1. The mandatory minimum penalty was amended to take effect for possession of crack cocaine in excess of 28 grams.[17]

Mandatory minimum penalties have been criticized for failing to apply uniformly to all cases of illegal behavior.[18]

Stop-and-frisk searches

The Supreme Court ruled in Terry v. Ohio that a "stop-and-frisk" search does not violate the Fourth Amendment, so long as the officer executing the search bears a "reasonable suspicion" that the person being searched has committed, or is about to commit, a crime. As a result, "stop-and-frisk" searches became much more common during the War on Drugs, and were generally conducted in minority communities.[19]

"Stop-and-frisk" searches have been criticized for being disproportionately carried out against minorities as a result of racial bias, though empirical literature on this count is inconclusive. Certain authors have found that, even after controlling for location and crime participation rates, African-Americans and Hispanics are stopped more frequently than whites.[4] Others have found that no bias exists, on average, in an officer's decision to stop a citizen, though bias may exist in an officer's decision to frisk a citizen.[20][21]

Stop-and-frisk searches in New York City have declined significantly since 2011.[22]

Crime statistics

Stops and searches

A 2015 report conducted by the Department of Justice found that blacks in Ferguson, Missouri were over twice as likely to be searched during vehicle stops, despite being found in possession of contraband 26% less often than white drivers.[24]

A 2016 report conducted by the San Francisco District Attorney's Office concluded that racial disparities exist regarding stops, searches, and arrests by the San Francisco Police Department, and that these disparities were especially salient for the black population. Blacks made up almost 42% of all non-consensual searches after a stop, though they accounted for less than 15 percent of all stops in 2015. Blacks held the lowest search "hit rate", meaning that contraband was least likely to be found during a search.[25]

A 2016 Chicago Police Accountability Task Force report found that black and Hispanic drivers were searched by the Chicago Police more than four times more frequently than white drivers, despite white drivers being found with contraband twice as often as black and Hispanic drivers.[26]

Arrests

A 1995 Bureau of Justice Statistics report found that from 1991 to 1993, 16% of those who sold drugs were black, but 49% of those arrested for doing so were black.[27]

A 2006 study concluded that blacks were significantly over-represented among those arrested for drug delivery offenses in Seattle. The same study found that this was a result of law enforcement focusing on crack offenders, on outdoor venues, and dedicating resources to racially heterogeneous neighborhoods.[28]

A 2010 study found little difference across races with regards to the rates of adolescent drug dealing.[29] A 2012 study found that African American youth were less likely than white youth to use or sell drugs, but more likely to be arrested for doing so.[30]

A 2013 study by the American Civil Liberties Union determined that a black person in the United States was 3.73 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than a white person, even though both races have similar rates of marijuana use.[31] Iowa had the highest racial disparity of the fifty states.[32] Black people in Iowa were arrested for marijuana possession at a rate 8.4 times higher than white people.[32] One factor that may explain the difference in arrest rates between whites and blacks is that blacks are more likely than whites to buy marijuana outdoors, from a stranger, and away from their homes.[33]

A 2015 study concluded that minorities have been disproportionately arrested for drug offenses, and that this difference "cannot be explained by differences in drug offending, non-drug offending, or residing in the kinds of neighborhoods likely to have heavy police emphasis on drug offending."[34]

Sentencing

In 1998, there were wide racial disparities in arrests, prosecutions, sentencing and deaths. African-Americans, who only comprised 13% of regular drug users, made up for 35% of drug arrests, 55% of convictions, and 74% of people sent to prison for drug possession crimes.[35] Nationwide African-Americans were sent to state prisons for drug offenses 13 times more often than white men.[36][37]

Crime statistics show that in 1999 in the United States blacks were far more likely to be targeted by law enforcement for drug crimes, and received much stiffer penalties and sentences than whites.[38] A 2000 study found that the disproportionality of black drug offenders in Pennsylvania prisons was unexplained by higher arrest rates, suggesting the possibility of operative discrimination in sentencing.[39]

A 2008 paper stated that drug use rates among Blacks (7.4%) were comparable to those among Whites (7.2%), meaning that, since there are far more White Americans than Black Americans, 72% of illegal drug users in America are white, while only 15% are black.[37]

According to Michelle Alexander, the author of The New Jim Crow and a professor of law at Stanford Law School, even though drug trading is done at similar rates all over the U.S., most people arrested for it are colored. Together, African American and Hispanics comprised 58% of all prisoners in 2008, even though African Americans and Hispanics make up approximately one quarter of the US population [40] The majority of prisoners are arrested for drug related crime, and in at least 15 states, 3/4 of them are black or Latino people.

A 2012 report by the United States Sentencing Commission found that drug sentences for black men were 13.1 percent longer than drug sentences for white men between 2007 and 2009.[41]

Rehabilitation

Professor Cathy Schnieder of International Service at American University notes that in 1989, African Americans, representing 12-15 percent of all drug use in the United States, made up 41 percent of all arrests. That is a noted increase from 38 percent in 1988. Whites were 47 percent of those in state-funded treatment centers and made up less than 10 percent of those committed to prison.[42]

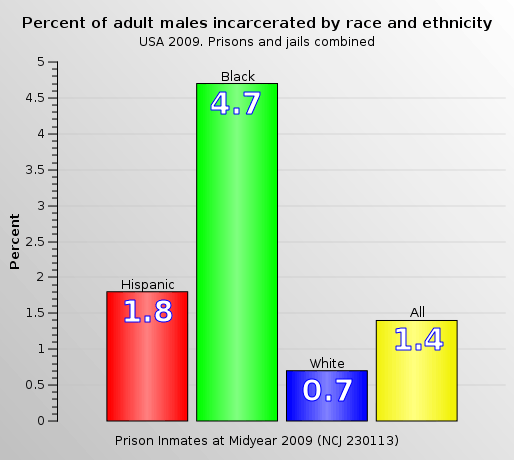

Percent incarcerated by race and ethnicity

| 2010. Inmates in adult facilities, by race and ethnicity. Jails, and state and federal prisons.[43] | |||

| Race, ethnicity | % of US population | % of U.S. incarcerated population |

National incarceration rate (per 100,000 of all ages) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 64 | 39 | 450 per 100,000 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 19 | 831 per 100,000 |

| Black | 13 | 40 | 2,306 per 100,000 |

Legal history

Some have suggested that certain Supreme Court rulings related to the War on Drugs have reinforced racially disproportionate treatment.[44]

In United States v. Armstrong (1996), the Supreme Court heard the case of Armstrong, a black man charged with conspiring to possess and distribute more than 50 grams of crack cocaine. Facing the District Court, Armstrong claimed that he was singled out for prosecution due to his race and filed a motion for discovery. The District Court granted the motion, and required the government to provide statistics from the prior 3 year on similar crimes, dismissing Armstrong's case when the government refused.

The government appealed the decision, and the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal, holding that defendants in selective-prosecution claims need not demonstrate that the government failed to prosecute similarly situated individuals. The case was then sent to the Supreme Court, which reversed the decision and held that defendants must show that the government failed to prosecute similarly situated individuals.[45]

In United States v. Bass (2002), the Supreme Court heard a similar case. John Bass was charged with two counts of homicide, and the government sought the death penalty. Bass filed for dismissal, along with a discovery request alleging that death sentences are racially motivated. When the government refused to comply with the discovery request, the District Court dismissed the death penalty notice. Upon appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal, and the case was sent to the Supreme Court.

Reversing the decision, the Supreme Court ruled that a defendant in a selective prosecution case must make a "credible showing" of evidence that the prosecution policy in question was intentionally discriminatory. The court ruled that Bass did not do so because he failed to show that similarly situated individuals of different races were treated differently. Specifically, the Court rejected Bass' use of national statistics, holding that they were not representative of similarly situated individuals.[46]

Both cases have been criticized for perpetuating racially motivated legal standards. It has been suggested that the current standard is impossible to meet for selective prosecution claims, because the relevant data may not exist, and if it does, because the prosecution may have sole access to it.[44]

Effects of the War on Drugs

Negative health effects

Felony drug convictions often lead to circumstances that carry negative health-related consequences. Employment opportunities (and associated healthcare benefits), access to public housing and food stamps, and financial support for higher education are all jeopardized, if not eliminated, as a result of such a conviction.[9] In addition, a felony distribution charge often precludes a convict from benefiting from most healthcare programs that receive federal funding.[8]

Collateral consequences

Some authors have suggested that the collateral consequences of criminal conviction are more serious than the legal penalties. In many cases, statutes do not require that convicts are informed of these consequences.[8] Many felons cannot be employed by the federal government or work in government jobs, as they do not meet the standards to gain security clearance. Felons convicted of distributing or selling drugs may not enlist in the military.[8]

Certain states are financially incentivized to exclude criminals from access to public housing. All states receive less federal highway funding if they fail to revoke or suspend driver's licenses of drug-related felons.[8]

Collateral consequences, and felon disenfranchisement in particular, have historically been at least partially racially motivated.[8][47]

African-American communities

The War on Drugs has incarcerated high numbers of African-Americans. However, the damage has compounded beyond individuals to affect African-American communities as a whole, with some social scientists suggesting the War on Drugs could not be maintained without societal racism and the manipulation of racial stereotypes.[48]

African-American children are over-represented in juvenile hall and family court cases,[49] a trend that began during the War on Drugs.[9] From 1985 to 1999, admissions of blacks under the age of 18 increased by 68%. Some authors posit that this over-representation is because minority juveniles commit crime more often, and commit more serious crimes.[50][51]

A compounding factor is often the imprisonment of a father. Boys with imprisoned fathers are significantly less likely to develop the skills necessary for success in early education.[52] In addition, African-American youth often turn to gangs to generate income for their families, oftentimes more effectively than at a minimum wage or entry level job.[53] Still, this occurs even as substance abuse, especially marijuana, has largely declined among high school students.[54] In contrast, many black youths drop out of school, are subsequently tried for drug-related crime, and acquire AIDS at disparate levels.[53]

In addition, the high incarceration rate has led to the juvenile justice system and family courts to use race as a negative heuristic in trials, leading to a reinforcing effect: as more African-Americans are incarcerated, the more the heuristic is enforced in the eyes of the courts. This contributes to yet higher imprisonment rates among African-American children.

High numbers of African American arrests and charges of possession show that although the majority of drug users in the United States are white, blacks are the largest group being targeted as the root of the problem.[55] Furthermore, a study by Andrew Golub, Bruce Johnson, and Eloise Dunlap affirms the racial divide in drug arrests, notably marijuana arrests, where blacks with no prior arrests (0.9%) or one prior arrest (4.3%) were nearly twice as likely to be sentenced to jail as their white counterparts (0.4% and 2.3%, respectively).[56] Harboring these emotions can lead to a lack of will to contact the police in case of an emergency by members of African-American communities, ultimately leaving many people unprotected. Disproportionate arrests in African-American communities for drug-related offenses has not only spread fear but also perpetuated a deep distrust for government and what some call racist drug enforcement policy.

Additionally, a black-white disparity can be seen in probation revocation, where black probationers were revoked at higher rates than white and Hispanic probationers in studies as published under The Urban Institute.[57]

Women of color

The War on Drugs also plays a negative role in the lives of women of color. The number of black women imprisoned in the United States increased at a rate more than twice that of black men, over 800% from 1986 to 1991. During that same period, the percentage of females incarcerated for drug-related offenses more than doubled.[58] In 1989, black and white women had similar levels of drug use during pregnancy. In spite of this, black women were 10 times as likely as white women to be reported to a child welfare agency for prenatal drug use.[59] In 1997, of women in state prisons for drug-related crimes, forty-four percent were Hispanic, thirty-nine percent were black, and twenty-three percent were white, quite different from the racial make up shown in percentages of the United States as a whole.[60] Statistics in England, Wales, and Canada are similar. Women of color who are implicated in drug crimes are "generally poor, uneducated, and unskilled; have impaired mental and physical health; are victims of physical and sexual abuse and mental cruelty; are single mothers with children; lack familial support; often have no prior convictions; and are convicted for a small quantity of drugs".[60]

Additionally, these women typically have an economic attachment to, or fear of, male drug traffickers, creating a power paradigm that sometimes forces their involvement in drug-related crimes.[61] Though there are programs to help them, women of color are usually unable to take advantage of social welfare institutions in America due to regulations. For example, women's access to methadone, which suppresses cravings for drugs such as heroin, is restricted by state clinics that set appointment times for women to receive their treatment. If they miss their appointment, (which is likely: drug-addicted women may not have access to transportation and lead chaotic lives), they are denied medical care critical to their recovery. Additionally, while women of color are offered jobs as a form of government support, these jobs often do not have childcare, rendering the job impractical for mothers, who cannot leave their children at home alone.[61]

However, with respect to mandatory minimum sentencing, female offenders receive relief almost 20% more often than male offenders.[62] In addition, female offenders, on average, receive lighter sentences than those who commit similar offenses.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Richard Nixon: Special Message to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- 1 2 Baum, Dan (2016-04-01). "Legalize It All". Harper's Magazine. ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- 1 2 3 "1995 Report to the Congress: Cocaine and Federal Sentencing Policy". United States Sentencing Commission. 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- 1 2 Gelman, Andrew; Fagan, Jeffrey; Kiss, Alex (2007-09-01). "An Analysis of the New York City Police Department's "Stop-and-Frisk" Policy in the Context of Claims of Racial Bias". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 102 (479): 813–823. doi:10.1198/016214506000001040. ISSN 0162-1459.

- ↑ "How the War on Drugs Damages Black Social Mobility | Brookings Institution". Brookings. 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ↑ Michael, Tonry, (2015-01-01). "Race and the War on Drugs". University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1994 (1). ISSN 0892-5593.

- ↑ Walters, John P. (1994). "Race and the War on Drugs". University of Chicago Legal Forum. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chin, Gabriel (2011-04-14). "Race, the War on Drugs, and the Collateral Consequences of Criminal Conviction". Rochester, NY. SSRN 390109.

- 1 2 3 Iguchi, M. Y.; Bell, James; Ramchand, Rajeev N.; Fain, Terry (2005-11-29). "How Criminal System Racial Disparities May Translate into Health Disparities". Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 16 (4): 48–56. doi:10.1353/hpu.2005.0114. ISSN 1548-6869. PMID 16327107.

- ↑ Analyst, By David Gergen, CNN Senior Political. "Opinion: The inner demons that drove Nixon - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ↑ Hanson, Hilary. "Nixon Aides Suggest Colleague Was Kidding About Drug War Being Designed To Target Black People". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- ↑ "H.R.5484 - Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986". Congress.gov. 27 October 1986. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ "NCJRS Abstract - National Criminal Justice Reference Service". www.ncjrs.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Crack Cocaine Sentencing Laws" (PDF). Families Against Mandatory Minimums. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ Thernstrom, Abigail; Thernstrom, Stephan (1999), "Crime", in Thernstrom, Abigail; Thernstrom, Stephan, America in black and white: one nation, indivisible, Simon and Schuster, p. 278, ISBN 9780684844978 Preview.

- ↑ McWhorter, John H. (2000), "The cult of victimology", in McWhorter, John H., Losing the race: self-sabotage in Black America, Simon and Schuster, p. 14, ISBN 9780684836690 Preview.

- ↑ "Fair Sentencing Act of 2010". Congress.gov. 3 August 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- 1 2 "NCJRS Abstract - National Criminal Justice Reference Service". www.ncjrs.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ↑ Cooper, Hannah LF (2015-01-01). "War on Drugs Policing and Police Brutality". Substance Use & Misuse. 50 (8–9): 1188–1194. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1007669. ISSN 1082-6084. PMC 4800748. PMID 25775311.

- ↑ "Analysis of Racial Disparities in the New York Police Department's Stop, Question, and Frisk Practices". 2007-01-01.

- ↑ Coviello, Decio; Persico, Nicola (2015-06-01). "An Economic Analysis of Black-White Disparities in the New York Police Department's Stop-and-Frisk Program". The Journal of Legal Studies. 44 (2): 315–360. doi:10.1086/684292. ISSN 0047-2530.

- ↑ "Stop-and-Frisk Data". New York Civil Liberties Union. 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ↑ Prison Inmates at Midyear 2009 - Statistical Tables (NCJ 230113). U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. The rates are for adult males, and are from Tables 18 and 19 of the PDF file. Rates per 100,000 were converted to percentages.

- ↑ "Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department" (PDF). United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ "The Blue Ribbon Panel on Transparency, Accountability, and Fairness in Law Enforcement" (PDF). SFDistrictAttorney.org. July 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Reform: Restoring Trust between the Chicago Police and the Communities they Serve" (PDF). April 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ "The Racial Disparity in U.S. Drug Arrests" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. 1 October 1995. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ BECKETT, KATHERINE; NYROP, KRIS; PFINGST, LORI (February 2006). "RACE, DRUGS, AND POLICING: UNDERSTANDING DISPARITIES IN DRUG DELIVERY ARRESTS*". Criminology. 44 (1): 105–137. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00044.x.

- ↑ Floyd, Leah J.; Alexandre, Pierre K.; Hedden, Sarra L.; Lawson, April L.; Latimer, William W.; Giles, Nathaniel (25 March 2010). "Adolescent Drug Dealing and Race/Ethnicity: A Population-Based Study of the Differential Impact of Substance Use on Involvement in Drug Trade". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 36 (2): 87–91. doi:10.3109/00952991003587469. PMC 2871399.

- ↑ Kakade, Meghana; Duarte, Cristiane S.; Liu, Xinhua; Fuller, Cordelia J.; Drucker, Ernest; Hoven, Christina W.; Fan, Bin; Wu, Ping (July 2012). "Adolescent Substance Use and Other Illegal Behaviors and Racial Disparities in Criminal Justice System Involvement: Findings From a US National Survey". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (7): 1307–1310. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300699. PMC 3477985. PMID 22594721.

- ↑ The war on marijuana in black and white: billions of dollars wasted on racially biased arrests (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. June 2013.

- 1 2 "Iowa ranks worst in racial disparities of marijuana arrests". ACLU of Iowa News. American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa. 4 June 2013.

- ↑ RAMCHAND, R; PACULA, R; IGUCHI, M (1 October 2006). "Racial differences in marijuana-users' risk of arrest in the United States". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 84 (3): 264–272. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.010.

- ↑ Mitchell, Ojmarrh; Caudy, Michael S. (22 January 2013). "Examining Racial Disparities in Drug Arrests". Justice Quarterly. 32 (2): 288–313. doi:10.1080/07418825.2012.761721.

- ↑ Burton-Rose, Daniel, ed. (1998). The Celling of America: An Inside Look at the U.S. Prison Industry. Common Courage Press. ISBN 1567511406.

possession of 500 grams of powdered cocaine--100 times the amount of crack--carries a 5 year minimum sentence" ... in reality a racist war being waged against poor Blacks

- ↑ "Key findings at a glance". Racial disparities in the war on drugs. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- 1 2 Moore, Lisa D.; Elkavich, Amy (May 2008). "Who's Using and Who's Doing Time: Incarceration, the War on Drugs, and Public Health". American Journal of Public Health. 98 (5): 782–786. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.126284. PMC 2518612.

- ↑ "I. Summary and recommendations". Punishment and Prejudice: Racial Disparities in the War on Drugs. Human Rights Watch. 2000. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ AUSTIN, R. L.; ALLEN, M. D. (1 May 2000). "Racial Disparity in Arrest Rates as an Explanation of Racial Disparity in Commitment to Pennsylvania's Prisons". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 37 (2): 200–220. doi:10.1177/0022427800037002003.

- ↑ West, Michelle Alexander (2012), "Chapter 3: The color of justice", in West, Michelle Alexander, The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness, Cornel (foreword) (Rev. ed.), New York: New Press, pp. 97–139, ISBN 9781595586438

- ↑ "2012 Report to the Congress: Continuing Impact of United States v. Booker on Federal Sentencing". United States Sentencing Commission. 2016-03-28. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ↑ Schnieder, C. (1998). "Racism, Drug Policy, and Aids". Political Science Quarterly. 113 (3): 427–446. doi:10.2307/2658075. Retrieved 15 Mar 2012.

- ↑ Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity. Briefing by Leah Sakala. May 28, 2014. Prison Policy Initiative. Figures calculated with US Census 2010 SF-1 table P42 and the PCT20 table series.

- 1 2 Coker, Donna (2003-01-01). "Foreword: Addressing the Real World of Racial Injustice in the Criminal Justice System". The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-). 93 (4): 827–880. doi:10.2307/3491312. JSTOR 3491312.

- ↑ "United States v. Armstrong". Oyez. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ "United States v. Bass". Oyez. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ Shapiro, Andrew L. (1993-01-01). "Challenging Criminal Disenfranchisement under the Voting Rights Act: A New Strategy". The Yale Law Journal. 103 (2): 537–566. doi:10.2307/797104. JSTOR 797104.

- ↑ Provine, Doris Marie (2011-01-01). "Race and Inequality in the War on Drugs". Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 7 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102510-105445.

- ↑ Alexander, Rudolph. "The Impact of Poverty on African American Children in the Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice Systems". Forum on Public Policy Online. 2010 (4). ISSN 1938-9809.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney L.; Steen, Sara; Bridges, George S. (2002-05-01). "Racial Disparities in the Punishment of Youth: A Theoretical and Empirical Assessment of the Literature". Social Problems. 49 (2): 194–220. doi:10.1525/sp.2002.49.2.194. ISSN 0037-7791.

- ↑ Bridges, George S.; Crutchfield, Robert D.; Simpson, Edith E. (1987-10-01). "Crime, Social Structure and Criminal Punishment: White and Nonwhite Rates of Imprisonment". Social Problems. 34 (4): 345–361. doi:10.2307/800812. ISSN 0037-7791.

- ↑ Haskins, Anna R. (2017-03-07). "Unintended Consequences: Effects of Paternal Incarceration on Child School Readiness and Later Special Education Placement". Sociological science. 1: 141–158. doi:10.15195/v1.a11. ISSN 2330-6696. PMC 5026124. PMID 27642614.

- 1 2 Joseph, J.; Pearson, P. G. (2016-07-26). "Black Youths and Illegal Drugs". Journal of Black Studies. 32 (4): 422–438. doi:10.1177/002193470203200404.

- ↑ Johnson, Renee M.; Fairman, Brian; Gilreath, Tamika; Xuan, Ziming; Rothman, Emily F.; Parnham, Taylor; Furr-Holden, C. Debra M. (2015-10-01). "Past 15-Year Trends in Adolescent Marijuana Use: Differences by Race/Ethnicity and Sex". Drug and alcohol dependence. 155: 8–15. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.025. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 4582007. PMID 26361714.

- ↑ Mitchell, Ojmarrh; Caudy, Michael S. (2015-03-04). "Examining Racial Disparities in Drug Arrests". Justice Quarterly. 32 (2): 288–313. doi:10.1080/07418825.2012.761721. ISSN 0741-8825.

- ↑ GOLUB, ANDREW; JOHNSON, BRUCE D.; DUNLAP, ELOISE (2007-01-01). "THE RACE/ETHNICITY DISPARITY IN MISDEMEANOR MARIJUANA ARRESTS IN NEW YORK CITY". Criminology & public policy. 6 (1): 131–164. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00426.x. PMC 2561263. PMID 18841246.

- ↑ Siddique, Julie A.; Belshaw, Scott H. (2016-07-01). "Racial Disparity in Probationers' Views about Probation". Race and Justice. 6 (3): 222–235. doi:10.1177/2153368715602932. ISSN 2153-3687.

- ↑ Miller, Susan L. (1998-02-12). Crime Control and Women: Feminist Implications of Criminal Justice Policy. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781452250489.

- ↑ Chasnoff, Ira J.; Landress, Harvey J.; Barrett, Mark E. (1990). "The prevalence of illicit-drug or alcohol use during pregnancy and discrepancies in mandatory reporting in Pinellas County, Florida". New England Journal of Medicine. 322 (17): 1202–1206. doi:10.1056/NEJM199004263221706. PMID 2325711.

During the six-month period in which we collected the urine samples, 133 women in Pinellas County were reported to health authorities after delivery for substance abuse during pregnancy. Despite the similar rates of substance abuse among black and white women in our study, black women were reported at approximately 10 times the rate for white women (P<0.0001), and poor women were more likely than others to be reported. We conclude that the use of illicit drugs is common among pregnant women regardless of race and socioeconomic status. If legally mandated reporting is to be free of racial or economic bias, it must be based on objective medical criteria.

- 1 2 Reynolds, Marylee (2008). "The war on drugs, prison building, and globalization: catalysts for the global incarceration of women". NWSA Journal. 20 (1): 72–95. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- 1 2 Windsor, Liliane C.; Benoit, Ellen; Dunlap, Eloise (2010). "Dimensions of oppression in the lives of impoverished Black women who use drugs". Journal of Black Studies. 41 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1177/0021934708326875. PMC 2992333. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ↑ "2011 Report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System". United States Sentencing Commission. 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

Further reading

Books

- Herbert J. Gans (1995). The war against the poor: the underclass and antipoverty policy. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01991-5.

- The New Jim Crow (2010) by Michelle Alexander www.newjimcrow.com ISBN 978-1595581037

- Jill McCorkel (2013). Breaking Women: Gender, Race, and the New Politics of Imprisonment. New York University Press.

Journal articles

- Martin, Dianne L. (1993). "Casualties of the Criminal Justice System: Women and Justice Under the War on Drugs". Canadian Journal of Women & the Law. 6 (2): 305–327.

- Hall, Mary F. (June 1997). "The "War on Drugs": A Continuation of the War on the African American Family". Smith College Studies in Social Work. 67 (3): 609–621. doi:10.1080/00377319709517509.

- Enid Logan (1999). "The Wrong Race, Committing Crime, Doing Drugs, and Maladjusted for Motherhood: The Nation's Fury over "Crack Babies"". Social Justice. 26 (1): 115–138. JSTOR 29767115.

- Gorton, Joe; Boies, John L (March 1999). "Sentencing Guidelines and Racial Disparity across Time: Pennsylvania Prison Sentences in 1977, 1983, 1992, and 1993". Social Science Quarterly. University of Texas Press. 80 (1): 37–54.

- JM Wallace (May 1999). "The social ecology of addiction: race, risk, and resilience". Pediatrics. 103 (5 Pt. 2): 1122–1127. PMID 10224199.

- Graham Boyd (July–August 2001). "The Drug War is the New Jim Crow". NACLA Report on the Americas. 35 (1): 18.

- Deborah Small (Fall 2001). "The War on Drugs Is a War on Racial Justice". Social Research. 68 (3): 896–903.

- Kenneth B. Nunn (2002). "Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the War on Drugs Was a War on Blacks". Gender, Race & Justice (6): 381

- Gabriel Chin (2002). "Race, the War on Drugs and the Collateral Consequences of Criminal Conviction". Gender, Race & Justice (6): 253. doi:10.2139/ssrn.390109. SSRN 390109

- Samuel R. Gross; Katherine Y. Barnes (December 2002). "Road Work: Racial Profiling and Drug Interdiction on the Highway". Michigan Law Review. 101 (3): 653–751. doi:10.2307/1290469.

- Beckett, Katherine; Nyrop, Kris; Pfingst, Lori; Bowen, Melissa (August 2005). "Drug Use, Drug Possession Arrests, and the Question of Race: Lessons from Seattle". Social Problems. 52 (3): 419–441. doi:10.1525/sp.2005.52.3.419.

- Banks, R. Richard (December 2003). "Beyond Profiling: Race, Policing, and the Drug War". Stanford Law Review. 56 (3): 571.

- Stephanie R. Bush-Baskette (2004). "12. "The War on Drugs as a War on Black Women"". In Meda Chesney-Lind; Lisa Pasko. Girls, women, and crime: selected readings. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-2828-7.

- Ruiz, Jim; Woessner, Matthew (Autumn 2006). "Profiling, Cajun style: racial and demographic profiling in Louisiana's war on drugs". International Journal of Police Science & Management. 8 (3): 176–197. doi:10.1350/ijps.2006.8.3.176.

- Illya Lichtenberg (March 2006). "Driving While Black (DWB): Examining Race as a Tool in the War on Drugs". Police Practice & Research. 7 (1): 49–60. doi:10.1080/15614260600579649.

- Katherine Beckett; Kris Nyrop; Lori Pfingst (February 2006). "Race, Drugs, and Policing: Understanding Disparities in Drug Delivery Arrests". Criminology. 44 (1): 105–137. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00044.x.

- Bobo, Lawrence D.; Victor Thompson (Summer 2006). "Unfair By Design: The War on Drugs, Race, and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System" (PDF). Social Research. 73 (2): 445–472.

- Andrew D. Black (Fall 2007). ""The War on People": Reframing "The War on Drugs" by Addressing Racism Within American Drug Policy Through Restorative Justice and Community Collaboration". University of Louisville Law Review. 46 (1): 177–197.

- Veda Kunins, Hillary; Bellin, Eran; Chazotte, Cynthia; Du, Evelyn; Hope Arnsten, Julia (March 2007). "The effect of race on provider decisions to test for illicit drug use in the peripartum setting". Journal of Women's Health. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 16 (2): 245–355. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0070. PMC 2859171. PMID 17388741.

- Beckett, Katherine (June 2008). "Drugs, Data, Race and Reaction: A Field Report". Antipode. 40 (3): 442–447. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00612.x.

- Fellner, Jamie (2009). "Race, Drugs, and Law Enforcement in the United States". Stanford Law & Policy Review. 20 (2): 257–291.

Conference papers

- Johnson, Devon (2003). "Round Up the Usual Suspects: African Americans' Views of Drug Enforcement Policies". Conference Papers -- American Association for Public Opinion Research.

- Holloway, Johnny (2006). "Past as Prologue: Racialized Representations of Illicit Substances and Contemporary U.S. Drug Policy". Conference Papers -- International Studies Association: 1–19.

- Jeff Yates; Andrew Whitford (2008). "Racial Dimensions of Presidential Rhetoric: The Case of the War on Drugs". Conference Papers -- Midwestern Political Science Association: 1.

News

- Erik Eckholm (May 6, 2008). "Reports Find Racial Gap in Drug Arrests". The New York Times.

- Webb, Gary. "War on drugs has unequal impact on black Americans." (Archive) San Jose Mercury News. August 20, 1996.