Quarterback kneel

In American football, a quarterback kneel, also called taking a knee, genuflect offense, or victory formation occurs when the quarterback immediately kneels to the ground, ending the play on contact, after receiving the snap. It is primarily used to run the clock down, either at the end of the first half or the game itself, in order to preserve a lead or a win. Although it generally results in a loss of a yard and uses up a down, it minimizes the risk of a fumble, which would give the other team a chance at recovering the ball.

Especially when the outcome of the game has been well decided, defenses will often give little resistance to the play as a matter of sportsmanship as well as to reduce injury risk on what is a relatively simple play. The quarterback is generally not touched and the act of intentionally taking the knee results in the play being over in all variations of the sport.

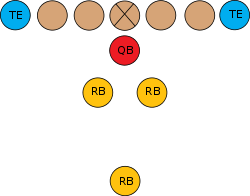

The formation offers maximum protection against a fumble; should the center-quarterback exchange result in a fumble, a running back is lined up on either side of the quarterback, both to recover any fumble and protect the vulnerable kneeling player from being injured by defensive players who get through the line. Also, a player is lined up directly behind the quarterback, often much farther than a typical tailback would line up. This player's responsibility is to tackle any defensive player who may recover a fumble and attempt to advance it. Because of this essentially "defensive" responsibility, the tailback in this formation may actually be a free safety or other defensive player who is adept at making tackles in the open field.

Even though the play itself takes very little time, the rules of American football dictate that it does not stop the game clock (as with any play where the ball carrier is tackled in bounds). With the 40-second play clock in the NFL and NCAA, along with the two-minute warning in the NFL, a team can run off over two minutes with three straight kneel-downs if the defensive team has no more timeouts. The winning team can storm the field if up to 40 seconds remains in the game (30 in Alliance of American Football), to let coaches shake hands with each other. (In the AAF, as many as three straight "victory formations" from 90 seconds left in regulation can be done.)

The play is often known as a "victory formation," as it is most often run by a winning team late in the game in order to preserve a victory. In the case of a close game, the winning team would be trying to avoid a turnover which might be the result of a more complex play. In the case of a more lopsided contest where the winning team's overall point differential has no prospect of affecting their playoff qualification prospects, the play can be run as a matter of sportsmanship (since the winning team foregoes the opportunity to run up the score) and to avoid further injury. In terms of statistics, a kneel by the quarterback is typically recorded as a rushing attempt for −1 or −2 yards.

Other sports also use the term "victory formation" for a play designed only to run down the clock with little chance of injury, such as a Jammer in roller derby skating behind or only lightly challenging the pack while the final seconds of the bout tick down.

Strategy

The quarterback kneel is mainly used when the team in the lead has possession of the ball with less than two minutes on the game clock. With the 40-second play clock in the NFL and NCAA, two minutes (120 seconds) is in theory the maximum amount of time that can be run off on three consecutive quarterback kneels; this assumes it is first down and the defense has no timeouts remaining. A team cannot run more than three consecutive quarterback kneels as doing so on fourth down turns the ball over to the opponent and guarantees them at least one opportunity to score. The decision to run the quarterback kneel depends on the amount of time remaining in the game, the down, and the number of timeouts the defense has remaining. For example, if there is one minute remaining on the game clock on first down, and the defense has one timeout left, the offense may use two successive quarterback kneels to completely run out the clock, and if the defense uses its timeout the offense can simply run a third kneel to run out the clock. However, if there is one minute remaining on the game clock on third down, then regardless of how many timeouts the defense has, quarterback kneels will not completely run out the clock and the offense must try to make a first down. AAF allows this to happen if up to 90 seconds remain; there's a 30-second play clock.

The quarterback kneel is also often used at the end of the first half by a team which feels they have little chance of scoring before halftime due to poor field position. It is also sometimes run at the end of the second half of a tie game by a team content with sending the game into overtime. Less commonly, the play is sometimes run at the end of the game by a losing team which is hopelessly behind and wishes to avoid injury, but is unwilling to cut the game short by forfeiting.

A team that is in field-goal range and either tied on the score or trailing by 1 or 2 points can also use one or more kneeldowns in order to run time off the clock before attempting a field goal. A quarterback in this situation may also run several yards to his left or right before kneeling down in order to get a more favorable spot for the field goal attempt, for example if the team's kicker prefers to kick from a specific side of the field. Ideally, the clock would run out during the field goal attempt, thereby preventing the opposing team from getting an opportunity to score again.

In several instances (including twice by the Philadelphia Eagles in the 2017 NFL season), a quarterback kneel has been purposefully initiated on a point after touchdown try at the end of the game after a game-winning or defensive touchdown was scored at the end of regulation; NFL rules used to require the try to be executed between the offense and defense, even if the offense intends to decline the unnecessary points to avoid further insulting or annoying their opponent. This occurred prominently in the 2018 "Minneapolis Miracle", where eight New Orleans Saints players on offense and defense had to return to the field from the locker room to 'oppose' the try against the victorious Minnesota Vikings after referee imploration to complete the try. Quarterback Case Keenum merely knelt the ball down before tossing it in the air and celebrating the Viking victory, with the Saints giving no effort to strip the ball (as a defensive runback for a two-point conversion would not have assured a tie or victory).[1] The rule was changed for 2018 onward, to omit the try if it would have no impact on the outcome of the game.

In rare instances, a team will use the quarterback kneel to avoid running up the score in a lopsided contest, even though there may be significant time remaining on the clock. This occurred in the 2011 edition of the Magnolia Bowl between the LSU Tigers and Ole Miss Rebels. With five minutes remaining and LSU leading 52–3, Tigers' head coach Les Miles ordered third-string quarterback Zach Mettenberger to kneel on first and goal from the Ole Miss one-yard line, and to kneel on the next three plays. Miles felt another touchdown would further embarrass Ole Miss coach Houston Nutt, who announced his resignation, effective at the end of the season, 12 days before the Rebels hosted first-ranked LSU. The Tigers had already secured the largest margin of victory in series history.

In Canadian football, which use slightly different rules, kneeling with time left is not necessarily a viable strategy. In the CFL, a quarter must end with a play.

History

Prior to the mid-1970s, teams leading in the final moments of games generally ran quarterback sneaks (which brought the risk of injuries on low-yardage plays) or dive plays to the fullbacks or other running backs to run time off the clock, as some coaches considered kneeling cowardly or even unsportsmanlike. However, the Miracle at the Meadowlands, on November 19, 1978, in which defensive back Herman Edwards of the visiting Philadelphia Eagles recovered a botched handoff between quarterback Joe Pisarcik and running back Larry Csonka of the New York Giants, provided a nationally-televised spur for change.

With 31 seconds remaining, the Giants led 17–12 and the Eagles were out of timeouts.[2][3] As Pisarcik attempted to hand it to Larry Csonka, it was awkwardly fumbled; Edwards scooped it up and ran it 26 yards for the Eagles' improbable 19–17 victory.[4][5] The play generated tremendous controversy, ridicule, and criticism toward the Giants nationwide and specifically offensive coordinator Bob Gibson for failing to use the supposedly foolproof quarterback-kneeldown play.

In the week following the game, both the Eagles and Giants developed specific formations designed to protect the quarterback behind three players as he fell on the ball. Previously, quarterbacks executing a similar "kill the clock" play simply ran a quarterback sneak from a tightly packed conventional offensive formation. The Eagles made the playoffs and the Giants finished at 6–10.

The "victory formation" spread rapidly throughout football at nearly all levels, as coaches sought to adopt a procedure for downing the ball in the final seconds which would reduce the risk of turnovers to the absolute minimum possible. Within a season or so, it had become nearly universal. In 1987 the NFL rule allowing quarterbacks to simply kneel and not have to fall down and risk a hit from the defense took effect.

Defense

Although in most instances a losing team will concede defeat when the other team is in the victory formation and taking the quarterback kneel, there are instances where the trailing team will try to make a defensive play in an attempt to regain possession of the ball, particularly when the losing team is behind by a touchdown or less and there is enough time to make more than one play.

This had happened on the play preceding The Miracle at the Meadowlands. Due to the low percentage of turnovers caused, defenses generally do not attempt to disrupt the kneeldown as the Eagles did in 1978; a "gentlemen's agreement" emerged in which defenders did not rush the offensive team with high intensity, as long as the offense made no attempt to advance the ball.

One prominent exception occurred to another Giants quarterback in 2012. In Week 2, an interception of a Tampa Bay Buccaneers pass with six seconds left had apparently secured a 25-point fourth-quarter comeback and 41–34 Giant victory. However, in the ensuing "victory formation" play, instead of the usual nominal contact between the lineman, the Buccaneers stacked the line of scrimmage and forcefully pushed the Giants' line back in an attempt to cause Giants' QB Eli Manning to fumble. Manning was knocked back by his own center as he took the snap and fell down. Giants coach Tom Coughlin angrily confronted his Tampa Bay counterpart, Greg Schiano, at midfield once the game was over.[6] Undaunted, Schiano employed a similar strategy the next week at the end of the Buccaneers' game against the Dallas Cowboys. In the next season, with the Philadelphia Eagles leading the Buccaneers, Chip Kelly had quarterback Nick Foles attempt a shotgun formation kneeldown to avert Schiano's aggressive technique, which succeeded.

Aside from trying to attempt a defensive play, teams that are losing but behind by a touchdown or less in the final two minutes will sometimes use their time-outs if the team does a quarterback kneel. As teams are allowed three time-outs per half—the clock stops on a time out and restarts on the snap—they will try to preserve them for situations such as this, thereby forcing the winning team to run a play and gain a first down or, in the very least, take time off the clock.

If there is still enough time left on the clock and the winning team attempts another quarterback kneel, the defensive team's strategy may repeat itself until it either runs out of time-outs, time runs out, or (most desirably) the team forces a punt or turnover, though in 2016, the Baltimore Ravens, leading in a game against the Cincinnati Bengals after three plays, ran off the remaining twelve seconds of clock off in a punt formation with Sam Koch purposefully holding the ball in the end zone while multiple holding calls were made against the Ravens offense. The play ended with Koch touching his toe to the back end zone line after time expired and taking an intentional safety (offensive fouls at the end of the game do not result in a replay of a down, unlike their defensive equivalents). The intentional holding aspect of the play was made illegal after the 2016 NFL season.

Rules

The 2011 NFL Rules state in Rule 7, Section 2, Article 1(c): "An official shall declare the ball dead and the down ended … when a quarterback immediately drops to his knee (or simulates dropping to his knee) behind the line of scrimmage".[7]

The 2011 and 2012 NCAA Rules state in Rule 4, Section 1, Article 3(o): "A live ball becomes dead and an official shall sound his whistle or declare it dead … When a ball carrier simulates placing his knee on the ground."[8] The same rule is used by the British American Football Association.[9]

The 2011 CFL Rules state in Rule 1, Section 4: "The ball is dead … When the quarterback, in possession of the ball, intentionally kneels on the ground during the last three minutes of a half".[10] The Statistical Scoring Rules, Section 5(e) states: "When a quarterback voluntarily drops to one knee and concedes yards in an effort to run out the clock, the yards lost will be charged under Team Losses. NOTE – No quarterback sack will be given in this situation."[11]

References

- ↑ Blackburn, Pete (14 January 2018). "Case Keenum leads Skol chant after throwing game-winning TD in playoffs". CBS Sports. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Chen, Albert (November 27, 1978). "A roundup of the week Nov 13-19: pro football". Sports Illustrated. p. 116.

- ↑ Chen, Albert (July 2, 2001). "The fumble". Sports Illustrated. p. 116.

- ↑ "Final play nightmare". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. November 20, 1978. p. 29.

- ↑ "Alas, New York, New York". Pittsburgh Press. UPI. November 20, 1978. p. B=6.

- ↑ Garafalo, Mike, "Coughlin to Schiano: 'You don't do that in this league'", USA Today, September 17, 2012. Accessed September 17, 2012.

- ↑ National Football League (2011), Official Playing Rules and Casebook of the National Football League (PDF), p. 35, retrieved 12 May 2012

- ↑ National Collegiate Athletic Association (May 2011), 2011 and 2012 NCAA Football Rules and Interpretations (PDF), p. FR-56, retrieved 12 May 2012

- ↑ British American Football Association (2012), Football Rules and Interpretations, 2012-13 edition (PDF), retrieved 12 May 2012

- ↑ Canadian Football League (2011), The Official Playing Rules for the Canadian Football League (PDF), p. 14, archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2012, retrieved 12 May 2012

- ↑ Canadian Football League (2011), The Official Playing Rules for the Canadian Football League (PDF), pp. 82, 88, archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2012, retrieved 12 May 2012