Protochronism

| Part of a series on the |

| Socialist Republic of Romania |

|---|

|

|

Relationship with the USSR |

|

Relations with other states |

Protochronism (anglicized from the Romanian: Protocronism, from the Ancient Greek terms for "first in time") is a Romanian term describing the tendency to ascribe, largely relying on questionable data and subjective interpretations, an idealized past to the country as a whole. While particularly prevalent during the regime of Nicolae Ceauşescu, its origin in Romanian scholarship dates back more than a century.

The term refers to perceived aggrandizing of Dacian and earlier roots of today's Romanians. This phenomenon is also pejoratively labelled "Dacomania" or sometimes "Thracomania", while its proponents prefer "Dacology".

Overview

In this context, the term makes reference to the trend (noticed in several versions of Romanian nationalism) to ascribe a unique quality to the Dacians and their civilization.[1] Protochronists attempt to prove either that Dacians had a major part to play in Ancient history, or even that they had the ascendancy over all cultures (with a particular accent on Ancient Rome, which, in a complete reversal of the founding myth, would have been created by Dacian migrants).[2] Also noted are the exploitation of the Tărtăria tablets as certain proof that writing originated on proto-Dacian territory, and the belief that the Dacian language survived all the way to the Middle Ages.[2]

An additional—but not universal—feature is the attempted connection between the supposed monotheism of the Zalmoxis cult and Christianity,[3] in the belief that Dacians easily adopted and subsequently influenced the religion. Also, Christianity is argued to have been preached to the Daco-Romans by Saint Andrew, who is considered, doubtfully, as the clear origin of modern-day Romanian Orthodoxy. Despite the lack of evidence to support this, it is the official church stance, being found in history textbooks used in Romanian Orthodox seminaries and theology institutes.[4]

History

The ideas have been explained as part of an inferiority complex present in Romanian nationalism,[5] one which also manifested itself in works not connected with Protochronism, mainly as a rejection of the ideas that Romanian territories only served as a colony of Rome, voided of initiative, and subject to an influx of Latins which would have completely wiped out a Dacian presence.[6]

Protochronism most likely came about with the views professed in the 1870s by Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu,[7] one of the main points of the dispute between him and the conservative Junimea. For example, Hasdeu's Etymologicum magnum Romaniae not only claimed that Dacians gave Rome many of her Emperors (an idea supported in recent times by Iosif Constantin Drăgan),[8] but also that the ruling dynasties of early medieval Wallachia and Moldavia were descendants of a caste of Dacians established with "King" (chieftain) Burebista.[9] Other advocates of the idea before World War I included the amateur archaeologist Cezar Bolliac,[10] as well as Teohari Antonescu and Nicolae Densuşianu. The latter composed an intricate and unsupported theory on Dacia as the center of European prehistory,[11] authoring a complete parallel to Romanian official history, which included among the Dacians such diverse figures as those of the Asen dynasty, and Horea.[11] The main volume of his writings is Dacia Preistorică ("Prehistoric Dacia").

After World War I and throughout Greater Romania's existence, the ideology increased its appeal. The Iron Guard flirted with the concept, making considerable parallels between its projects and interpretations of what would have been Zalmoxis' message.[12] Mircea Eliade was notably preoccupied with Zalmoxis' cult, arguing in favor of its structural links with Christianity;[13] his theory on Dacian history, viewing Romanization as a limited phenomenon, is celebrated by contemporary partisans of Protochronism.[14]

In a neutral context, the Romanian archaeology school led by Vasile Pârvan investigated scores of previously ignored Dacian sites, which indirectly contributed to the idea's appeal at the time.[15]

In 1974 Edgar Papu published in the mainstream cultural monthly Secolul XX an essay titled "The Romanian Protochronism", arguing for Romanian chronological priority for some European achievements.[16] The idea was promptly adopted by the nationalist Ceauşescu regime, which subsequently encouraged and amplified a cultural and historical discourse claiming the prevalence of autochthony over any foreign influence.[17] Ceauşescu's ideologues developed a singular concept after the 1974 11th Congress of the Communist Party of Romania, when they attached Protochronism to official Marxism, arguing that the Dacians had produced a permanent and "unorganized State".[18] The Dacians had been favored by several communist generations as autochthonous insurgents against an "Imperialist" Rome (with the Stalinist leadership of the 1950s proclaiming them to be closely linked with the Slavic peoples);[19] however, Ceauşescu's was an interpretation with a distinct motivation, making a connection with the opinions of previous protochronists.[20]

The regime started a partnership with Italian resident, former Iron Guardist and millionaire Iosif Constantin Drăgan, who continued championing the Dacian cause even after the fall of Ceauşescu.[21] Critics regard these excesses as the expression of an economic nationalist course, amalgamating provincial frustrations and persistent nationalist rhetoric, as autarky and cultural isolation of the late Ceauşescu's regime came along with an increase in protochronistic messages.[22]

No longer backed by a totalitarian state structure after the 1989 Revolution, the interpretation still enjoys popularity in several circles.[23] The main representative of current Protochronism is still Drăgan, but he is seconded by the New York City-based physician Napoleon Săvescu. Together, they issue the magazine Noi, Dacii ("We Dacians") and organize a yearly "International Congress of Dacology".[24]

Dacian script

Dacian alphabet is a term used in Romanian Protochronism for pseudohistorical claims of a supposed alphabet of the Dacians prior to the conquest of Dacia and its absorption into the Roman Empire. Its existence was first proposed in the late 19th century by Romanian nationalists, but has been completely rejected by mainstream modern scholarship.

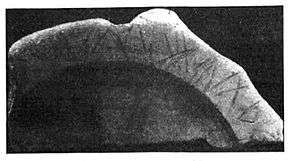

In the opinion of Sorin Olteanu, a modern expert at the Vasile Pârvan Institute of Archaeology, Bucharest, "[Dacian script] is pure fabrication [...] purely and simply Dacian writing does not exist", adding that many scholars believe that the use of writing may have been subject to a religious taboo among the Dacians.[25] It is known that the ancient Dacians used the Greek and Latin alphabets,[26] though possibly not as early as in neighbouring Thrace where the Ezerovo ring in Greek script has been dated to the 5th century BC. A vase fragment from the La Tène period (Fig., right), a probable illiterate imitation of Greek letters, indicates visual knowledge of the Greek alphabet [27] during the La Tène period prior to the Roman invasion. Some Romanian writers writing at the end of the 19th century and later identified as protochronists, particularly the Romanian poet and journalist Cezar Bolliac, an enthusiast amateur archeologist,[28] claimed to have discovered a Dacian alphabet. They were immediately criticized for archeological[29] and linguistic[30][31] reasons. Alexandru Odobescu, criticized some of Bolliac's conclusions.[32] In 1871 Odobescu, along with Henric Trenk, inventoried the Fundul Peşterii cave, one of the Ialomiţei caves (See the Romanian Wikipedia article) near Buzău. Odobescu was the first to be fascinated by its writings, which were later dated to the 3rd or 4th century.[33] In 2002, the controversial[34] Romanian historian, Viorica Enăchiuc, stated that the Codex Rohonczi is written in a Dacian alphabet.[35] The equally controversial[36] linguist Aurora Petan (2005) claims that some Sinaia lead plates could contain unique Dacian scripts.[37]

The main critic of protochronism in Romania, Lucian Boia (lector of History University at Bucharest), was heavily criticized by two PhD historians, both members of Romanian Academy, Ion Aurel Pop, rector at Babes-Boliay University from Cluj-Napoca and professor Ioan Scurtu.[38]

What Pop says about Boia is that Boia is a specialist in 20th century historiography (i.e. protochronism), but Boia isn't a specialist in ancient or medieval history. So Pop does not disagree with the negative arguments mounted by Boia (i.e. dispelling the myths of National-Communist historiography), but says that Boia is unable to provide positive knowledge about the ancient and medieval history of Romania.[39] E.g. Boia's 2015 book about Mihai Eminescu is a book about the myths about Eminescu (i.e. imagology), it isn't a book about Eminescu's life (i.e. the facts about him).

Lucian Boia was accused as well that during Communist period he followed strictly the history line imposed by the Party as he was the head of communist propaganda department from Bucharest University.[38]

He started to become a critic just after 1989, when he became related with Soros Foundation which published his books at their publishing house in Budapest, Hungary. He was supported later on political basis, and he was advanced directly lector, jumping over pre-lector position as it was normal, and received grants for studies abroad (both before 1989, when agreement and preparation from former political secret police, Securitate, was needed for such, and after).[38]

Romanian nationalists compared him with Mihai Roller, the chief historian imposed by Soviets during 50's, famous for his attempts to rewrite national history and who was promptly eliminated from mainstream history circles even since the 60's. Boia was criticized as well because he is just a historian of ideas (i.e. how others write history) and not a specialist in historical domains he is talking about (like ancient history, medieval history, ethnology, archeology or linguistics), so his opinion in those subjects doesn't hold the necessary weight.[39]

Protochronism in other countries

During the 1940s, protochronism in the Soviet Union claimed that Russians had been the first to invent the lightbulb and telephone.[40] Imitating Stalinist trends in the Communist Bloc, Albania developed its own version of protochronist ideology which stressed the continuity of Albanians from ancient peoples such as the Illyrians.[40][41][42] Macedonians from the Republic of Macedonia have also engaged in protochronism claiming a Slavic-Thracian ethnogenesis.[41]

Notes

- ↑ Boia, p.160-161

- 1 2 Boia, p.149-151

- ↑ Boia, p.169

- ↑ Lavinia Stan, Lucian Turcescu, Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania, Oxford University Press, 2007, p.48

- ↑ Verdery, p.177

- ↑ Boia, p.85, 127-147

- ↑ Boia, 138-139, 140, 147; Verdery, p.326

- ↑ Boia, p.268

- ↑ Boia, p.82

- ↑ Boia, p.139-140

- 1 2 Boia, p.147-148

- ↑ Boia, p.320

- ↑ Boia, p.152; Eliade, "Zalmoxis, The Vanishing God", in Slavic Review, Vol. 33, No. 4 (December 1974), p.807-809

- ↑ Boia, p.152; Şimonca

- ↑ Boia, p.145-146

- ↑ Boia, p.122-123; Martin

- ↑ Boia, p.117-126

- ↑ Boia, p.120

- ↑ Boia, p.154-155, 156

- ↑ Boia, p.155-157; 330-331

- ↑ Verdary, p.343

- ↑ Boia, p.338

- ↑ Babeş; Boia, p.356

- ↑ "Ca şi cînd precedentele reuniuni n-ar fi fost de ajuns, dacologii bat cîmpii in centrul Capitalei", in Evenimentul Zilei, 22 June 2002

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-01-07. Retrieved 2011-01-09. "Este un bun prilej să demontăm un alt mit drag tracomanilor, anume cel al 'scrierii dacice' si al vechimii ei 'imemorabile'. 'Scrierea dacă' este pură inventie. Nu este nici măcar vorba de incertitudini, de chestiuni de interpretare (din ce punct de vedere privim) s.a.m.d., ci pur si simplu nu există nici o scriere dacă [...] Asa cum cred multi dintre învătati, este foarte posibil ca la daci, întocmai ca si la celti până la un anumit moment, scrierea să fi fost supusă unui tabu religios.

- ↑ Daicoviciu, Hadrian (1972). Dacii. Editura Enciclopedică Română.

- ↑ Dacia.Recherches et découvertes archéologiques en Roumanie. vol 3-4 (in French). 1933. p. 342. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

On ne possède malheureusement pas de plus grand fragment pour établir s'il s'agit d'une inscription en langue latine ou grecque, éventullement gète,, ou plutôt d'une ornementation grossière en forme d'alphabet , oeuvre probable d'un potier illetré. Ce tesson présente dans tous les cas un grand intérêt au point de vue de l'influence méridionale sur les artisans de notre station de Poiana, à la fin de l'époque Latène, à laquelle il appartient. Même s'il ne s'agit que d'un jeu d'imitation de quelque potier gète, sa connaissance approximative des lettres grecques ou romaines prouve que les relations entre les Gètes de la Moldavie et le monde gréco-romain d'outre Danube étaient devenues extrêmement étroites à la veille de la directe expansion romaine en Dacie.

- ↑ Măndescu, Dragos. "DESCOPERIREA SITULUI ARHEOLOGIC DE LA ZIMNICEA ŞI PRIMA ETAPĂ A CERCETĂRII SALE: 'EXPLORAŢIUNILE' LUI CEZAR BOLLIAC (1845, 1858?, 1869, 1871-1873)" (PDF). Museul Judetean Teleorman (in Romanian). Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Boia, p.92

- ↑ Hovelacque, Abel (1877). The science of language: linguistics, philology, etymology. Chapmanand Hall. p. 292. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

The Rumanian writer Eajden... fancies he has lighted upon the old Dacian alphabet, in an alphabet surviving till the last century amongst the Szeklers of Transylvania. But he has altogether overlooked the preliminary question, to what group of languages Dacian may belong.

- ↑ Le Moyen âge (in French). Champion. 1888. p. 258.

La théorie d'un alphabet dace est une fable; les caractères cyrilliques sont d'origine slave, non roumaine. Ce n'est que depuis le XV^ siècle que le peuple roumain les a admis dans son idiome national.

- ↑ Oisteanu, Andrei (April 30, 2008). "Scriitorii romani si narcoticele (1) De la Scavinski la Odobescu". 22 Revista Grupului Pentru Dialog Social (in Romanian). Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Popescu, Florentin. "Les ermitages des Monts de Buzau". Le site des monuments rupestres (in French). Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Ungureanu, Dan (May 6, 2003). "Nu trageti in ambulanta". Oservator Cultural (in Romanian). Archived from the original on March 27, 2004. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ↑ Enăchiuc, Vioroca (2002). Rohonczi Codex: descifrare, transcriere si traducere (Déchiffrement, transcription et traduction) (in Romanian and French). Editura Alcor. ISBN 973-8160-07-3.

- ↑ Olteanu, Sorin. "Raspuns Petan". Thraco-Daco-Moesian Languages Project (in Romanian). Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Petan, Aurora. "A possible Dacian royal archive on lead plates". Antiquity. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Ioan Scurtu. Editura Mica Valahie, ed. Istoria Romanilor de la Carol I la Nicolae Ceausescu (in Romanian). Editura Mica Valahie. p. 33. ISBN 978-606-8304-05-2.

- 1 2 Acad. prof. univ. dr. Ioan-Aurel Pop - Despre falsificarea istoriei on YouTube

- 1 2 Priestland, David (2009). The Red Flag: Communism and the making of the modern world. London: Penguin UK. p. 404. ISBN 9780141957388. "Protochronism became an enormously popular idea in Romanian culture in the 1970s and 1980s... Protochronism, of course had been seen before, in the Soviet claims of the 1940s that Russians had invented the telephone and the lightbulb. This was no accident. Romania was essentially importing a version of high Stalinism: a politics of hierarchy and discipline was wedded to an economics of industrialization and an ideology of nationalism. It was joined in this strategy by Albania"

- 1 2 Stan, Lavinia; Turcescu, Lucian (2007). Religion and politics in post-communist Romania. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780195308532.

- ↑ Tarţa, Iustin Mihai (2012). Dynamic civil religion and religious nationalism: the Roman Catholic Church in Poland and the Orthodox Church in Romania, 1990-2010 (Ph.D.). Baylor University. p. 78. Retrieved 20 April 2017. "The official doctrine that Ceaușescu adopted was called Dacianism, Romania is not the only country to invoke its ancient roots when it comes to show national superiority, Albania also emphasized its Thraco-Illyrian origin."

References

- Mircea Babeş, "Renaşterea Daciei?", in Observator Cultural, August 2001

- Lucian Boia, Istorie şi mit în conştiinţa românească, Bucharest, Humanitas, 1997

- B. P. Hasdeu, Ethymologicum Magnum Romaniae. Dicţionarul limbei istorice şi poporane a românilor (Pagini alese), Bucharest, Minerva, 1970

- (in Romanian) Mircea Martin, "Cultura română între comunism şi naţionalism" (II), in Revista 22, 44 (660)/XIII, October–November 2002

- (in Romanian) Ovidiu Şimonca, "Mircea Eliade şi 'căderea în lume'", review of Florin Ţurcanu, Mircea Eliade. Le prisonnier de l'histoire, in Observatorul Cultural

- Katherine Verdery, National Ideology under Socialism. Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceauşescu's Romania, University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 0-520-20358-5

External links

- www.dacii.ro: A site displaying prominent characteristics of Romanian Protochronism.

- www.dacia.org: A site connected with Săvescu.

- Monica Spiridon's essay on the intellectual origins of Romanian Protochronism.

- Historical myths, legitimating discourses, and identity politics in Ceauşescu's Romania (Part 1), (Part 2)

- Tracologie şi Tracomanie (Thracology and Thracomania) at Sorin Olteanu's LTDM Project (SOLTDM.COM)

- Teme tracomanice (Thracomaniacal Themes) at Sorin Olteanu's LTDM Project (SOLTDM.COM)