Pre-Christian Slavic writing

Pre-Christian Slavic writing is a hypothesized writing system that may have been used by the Slavs prior to Christianization and the introduction of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets. No extant evidence of pre-Christian Slavic writing exists, but early Slavic forms of writing or proto-writing may have been mentioned in several early medieval sources.

Evidence from early historiography

The 9th century Bulgarian[1] writer, Chernorizets Hrabar in his work An Account Of Letters (Bulgarian: О писменех, O pismeneh) briefly mentioned that, before Christianization, Slavs used a system he had dubbed "strokes and incisions" or "tallies and sketches" in some translations (Old Church Slavonic: чръты и рѣзы). He also provided information critical to Slavonic palaeography with his book.

Before, the Slavs did not have their own books, but read and divined by means of strokes and incisions, being pagan. Having become Christian, they had to make do with the use of Roman and Greek letters without order [unsystematically], but how can one write [Slavic] well with Greek letters...[note 1] and thus it was for many years.

— [2]

Another contemporaneous source, Thietmar of Merseburg, describing a temple on the island of Rügen, a Slavic pagan stronghold, remarked that the idols there had their names carved out on them ("singulis nominibus insculptis," Chronicon 6:23 ).[3]

Ahmad ibn Fadlan describes the manners and customs of the Rus, who arrived on a business trip in Volga Bulgaria. After a ritual ship burial of their dead tribesmen, Rus left an inscription on the tomb:

Then they constructed in the place where had been the ship which they had drawn up out of the river something like a small round hill, in the middle of which they erected a great post of birch wood, on which they wrote the name of the man and the name of the Rus king and they departed.

— [4]

However, Ibn Fadlan doesn't leave many clues about the ethnic origin of the people he described (see Rus).

Evidence from archaeology

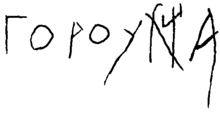

- In 1949, a Kerch amphora was found from Gnezdovo in Smolensk Oblast with the earliest inscription attested in the Old Russian language. The excavator has inferred that the word гороухща (goruhšča), inscribed on the pot in Cyrillic letters, designates mustard that was kept there.[5] This explanation has not been universally accepted and the inscription seems to be open to different interpretations.[6] The dating of the inscription to the mid-10th century[7] suggests a hitherto unsuspected popularity of the Cyrillic script in pre-Christian Rus.

- Of the three Runic inscriptions found in ancient Rus, only one, from Ladoga, predates the Gnezdovo inscription.

Evidence from etymology

The Slavic word for "to write", pьsati (Polish: pisać, Russian: писать, Czech: psát, Slovak: písať) derives from a Common Balto-Slavic word for "to paint, smear", found in Lithuanian piẽšti "paint, write", paĩšas "smudge", puišinas "sooty, dirty", from the same root as Old Slavic pьstrъ (also pěgъ) "coloured" (Greek ποικίλος), ultimately from a PIE root *peik- "speckled, coloured" (Latin pingō "paint", Tocharian pik-, pink- "paint, write"). This indicates that the Slavs named the new art of writing in ink, as "smearing, painting", unlike English which, with Old English *(w)rītan English write, transferred the term for "incising (runes)" to manuscript writing. The other Germanic languages use terms derived from Latin scribere. A Slavic term for "to incise" survives in OCS žrěbъ "lot" originally the incision on a wooden chip used for divination (Russian жребий "number, tally mark", from the same root as Greek γράφω).

Evidence against

In the "Life of Saint Cyril-Constantine the Philosopher", Rastislav, the duke of Moravia sent an embassy to Constantinople asking Emperor Michael III to send learned men to the Slavs of Great Moravia, who being already baptised, wished to have the liturgy in their own language, and not Latin and Greek. Emperor called for Constantine and asked him if he would do this task, even though being in poor health. Constantine replied that he would gladly travel to Great Moravia and teach them, as long as the Slavs had their own alphabet to write their own language in, to which the Emperor replied that not even his grandfather and father and let alone he could find any evidence of such an alphabet. Constantine was distraught, and was worried that if he invents an alphabet for them he'll be labelled a heretic.

Събравъ же съборъ Цѣсар̑ь призъва Кѡнстантїна Фїлософа, и сътвори и слꙑшати рѣчь сьѭ. И рече: Вѣмь тѧ трѹдьна сѫшта, Фїлософе, нъ потрѣба ѥстъ тебѣ тамо ити; сеѩ бо рѣчи не можетъ инъ никътоже исправити ꙗкоже тꙑ. Отъвѣшта же Фїлософъ: И трѹдьнъ сꙑ и больн̑ь тѣломь, съ радостьѭ идѫ тамо, аште имѣѭтъ бѹкъви въ ѩзꙑкъ свой. И рече Цѣсар̑ь къ нѥмѹ: Дѣдъ мой и отьць и ини мъноѕи искавъше того, не сѫтъ того обрѣли, то како азъ могѫ то обрѣсти? Фїлософъ же рече: То къто можетъ на водѫ бесѣдѫ напьсати и ѥретїчьско имѧ обрѣсти?

— Life of Saint Cyril-Constantine the Philosopher, Chapter XIV

Even if some form of writing existed among the Slavs in previous centuries, by the 9th century the learned men in the Eastern Roman Empire were not aware of its existence in any of the Slavic lands that they had sent missionaries or ambassadors to. Either this writing had died out or it wasn't a real form of writing, but rather just "tallies and sketches" as mentioned in Chernorizets Hrabar's An Account Of Letters, using which books could not be written.

Footnotes

See also

References

- ↑ http://pravoslavieto.com/history/09/Chernorizets_Hrabur/index.htm#bio

- ↑ Old Church Slavonic text of An Account of Letters (a Russian site) Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Thietmarus Merseburgensis

- ↑ Ibn Fadlan, on the Rus merchants at Itil, 922.

- ↑ The Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, 2nd ed. Article "Гнездовская надпись".

- ↑ Roman Jakobson, Linda R. Waugh, Stephen Rudy. Contributions to Comparative Mythology. Walter de Gruyter, 1985. Page 333.

- ↑ The latest coins found in the same burial go back to 295 AH, i.e. to 906–907 CE.