Population geography

Population geography is a division of human geography. It is the study of the ways in which spatial variations in the distribution, composition, migration, and growth of populations are related to the nature of places. Population geography involves demography in a geographical perspective.[lower-alpha 1] It focuses on the characteristics of population distributions that change in a spatial context. This often involves factors such as where populations are found and how the size and composition of these populations is regulated by the demographic processes of fertility, mortality, and migration.[1] Contributions to population geography are cross-disciplinary because geographical epistemologies related to environment, place and space have been developed at various times.[2] Related disciplines include geography, demography, sociology, and economics.

Since its inception, population geography has taken at least three distinct but related forms, the most recent of which appears increasingly integrated with human geography in general. The earliest and most enduring form of population geography emerged in the 1950s, as part of spatial science. Pioneered by Glenn Trewartha, Wilbur Zelinsky, William A. V. Clark, and others in the United States, as well as Jacqueline Beujeau-Garnier and Pierre George in France, it focused on the systematic study of the distribution of population as a whole and the spatial variation in population characteristics such as fertility and mortality.[1] Population geography defined itself as the systematic study of:

- the simple description of the location of population numbers and characteristics

- the explanation of the spatial configuration of these numbers and characteristics

- the geographic analysis of population phenomena (the inter-relations among real differences in population with those in all or certain other elements within the geographic study area).

Accordingly, it categorized populations as groups synonymous with political jurisdictions representing gender, religion, age, disability, generation, sexuality, and race, variables which go beyond the vital statistics of births, deaths, and marriages.[1] Given the rapidly growing global population as well as the baby boom in affluent countries such as the United States, these geographers studied the relation between demographic growth, displacement, and access to resources at an international scale.[1]

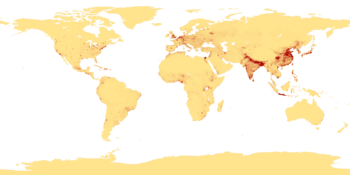

Examples can be shown through population density maps. A few types of maps that show the spatial layout of population are choropleth, isoline, and dot maps.

Case studies

Suburbanization

Suburbanization in the developed part of North America has roots in the migration decisions of many families who leave central cities and relocate on the urban fringe. This type of metropolitan decentralization matters because it contributes to the pressures on rural and "green-field" land, the under-funding of inner-city schools, the continuing segregation of groups in society, and the difficulties some suburban housewives encounter in finding jobs.[3]

Israel and Palestine

When the political creation of Israel was brokered in 1948, the act of drawing boundaries created new populations and divided others. Specifically, the displacement of thousands of residents of the former Palestine and the wholesale destruction of over 500 Arab villages created a refugee population that is, today, the world’s largest (over 4 million) and longest-lasting, including over two generations. Palestinian refugee communities lack access to human rights, protection, territorially rooted homelands and land that can support reasonable livelihoods. Refugee populations are some of the world’s poorest, most insecure, most fragile, and most dependent communities. While poverty and endemic insecurity characterize Palestinian refugees, the state of Israel is both threatened by the co-presence of this refugee community and complicit/active in its maintenance, through acts purported as securing the state.[3]

Tuberculosis in immigrants

Tuberculosis (TB) was a leading cause of death among young men and women in many North American cities at the turn of the 20th century. Medical discoveries about the spread of the disease and childhood vaccinations helped to decrease TB infections and case mortality rates declined steadily during the century. However, by the early 1990s, figures by place of birth suggested that foreign-born persons were eight times more likely to die from TB than native-born Americans. By studying the geographic context of disease, it becomes apparent that TB is less a marker of immigration than it is of poverty. Increasing TB levels in parts of the former Soviet Union territories and Haiti suggest that unemployment, poor access to underfunded healthcare systems, and stress all elevate risk. Immigrants also do not seem to be bringing TB to the United States but instead developing TB once inside the country. Concentrations of TB among immigrants in non-traditional destination states may suggest poor agricultural working conditions, barriers to accessing healthcare, and concentrations of refugee groups in unhealthy areas.[3]

Africa’s baby boom

Africa has now become the fastest-growing and fastest-urbanizing continent. Africa's population is estimated to reach two billion by 2050. As countries get richer, they experience a demographic transition. Africa's people are its biggest asset; one day, its workforce could be as robust and dynamic as Asia's. But there is nothing inevitable about the ability to cash in the demographic dividend. For that to happen, Africa will have to choose the right policies and overcome its many problems.[4]

Global population aging

The traditional United Nations definition of retirees is defined as age 65.[3] The population aging that is presently occurring is unprecedented. Over the next decade, the number of people aged 60 years and over is expected to rise substantially, and most of the increase will occur in developing countries. Globally, the number of older persons is expected to exceed the number of children in 2045 for the first time.[5]

The rapidly aging population is likely to have far-reaching effects. Economically, population aging affects growth, savings, investments, consumption, labor markets, social security systems, taxation, and inter-generational transfers. Socially, it influences family structures, housing demands, migration trends, and the epidemiology of diseases and the need for healthcare service. Politically, it shapes voting patterns and representation.[5] Population aging has received considerable attention in developed countries, but only in the past few decades has awareness of the ramifications of a rapidly aging population grown in the rest of the world.[6]

Others

- Demographic phenomena (natality, mortality, growth rates, etc.) through both space and time

- Increases or decreases in population numbers

- The movements and mobility of populations

- Occupational structure

- The way in which places in turn react to population phenomena, e.g. immigration

Research topics of other geographic sub-disciplines, such as settlement geography, also have a population geography dimension:

- The grouping of people within settlements

- The way from the geographical character of places, e.g. settlement patterns

All of the above are looked at over space and time. Population geography also studies the relationships between man and his environment, including problems from those relationships, such as overpopulation, pollution, and others.

See also

Notes

- ↑ While population geography focuses on the impacts of population on spatial structures and processes, geodemography analyzes the effects of space on demographic structures and processes. However, the boundary between population geography and demography is becoming more and more blurred.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Castree, N., Kitchin, Rogers. "population geography. In A Dictionary of Human Geography". Penn State Library.

- ↑ Gresh A. & Maharaj P. "Policy and Programme Responses". Penn State Library.

- 1 2 3 4 Bailey, A. (2014). Making population geography. Retrieved from http://sk8es4mc2l.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=sersol&SS_jc=TC0000422501&title=Making%20population%20geography

- ↑ The Baby Bonanza; Africa's Population. (2009, Aug 29). The Economist, 392, 21-24. Retrieved from http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/docview/223965384?accountid=13158

- 1 2 (2011), Department of Economic and Social Affairs; World Population Ageing 2009. Population and Development Review, 37: 403. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00421.xhttp://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/doi/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00421.x/abstract

- ↑ Gresh A., Maharaj P. (2013) Policy and Programme Responses. In: Maharaj P. (eds) Aging and Health in Africa. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 4. Springer, Boston, MA. https://link-springer-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4419-8357-2_11#citeas

- Clarke, John I. Population Geography. London: Pergamon Press, 1965.