Polytrope

In astrophysics, a polytrope refers to a solution of the Lane–Emden equation in which the pressure depends upon the density in the form

where P is pressure, ρ is density and K is a constant of proportionality.[1] The constant n is known as the polytropic index. The polytropic exponent γ = (n+1)/n is sometimes preferred over n. This relation need not be interpreted as an equation of state, although a gas following such an equation of state does produce a polytropic solution to the Lane–Emden equation. Rather, this is simply a relation that expresses an assumption about the change of pressure with radius in terms of the change of density with radius, yielding a solution to the Lane–Emden equation.

Sometimes the word polytrope may be used to refer to an equation of state that looks similar to the thermodynamic relation above, although this is potentially confusing and is to be avoided. It is preferable to refer to the fluid itself (as opposed to the solution of the Lane–Emden equation) as a polytropic fluid. The equation of state of a polytropic fluid is general enough that such idealized fluids find wide use outside of the limited problem of polytropes.

The polytropic exponent (of a polytrope) has been shown to be equivalent to the pressure derivative of the bulk modulus [2] where its relation to the Murnaghan equation of state has also been demonstrated. The polytrope relation is therefore best suited for relatively low-pressure (below 107 pascals) and high-pressure (over 1014 pascals) conditions when the pressure derivative of the bulk modulus, which is equivalent to the polytrope index, is near constant.

Example models by polytropic index

- Neutron stars are well modeled by polytropes with index between n = 0.5 and n = 1.

- A polytrope with index n = 1.5 is a good model for fully convective star cores[3][4](like those of red giants), brown dwarfs, giant gaseous planets (like Jupiter), or even for rocky planets.

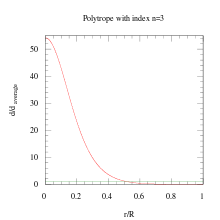

- Main sequence stars like our Sun and relativistic degenerate cores like those of white dwarfs are usually modeled by a polytrope with index n = 3, corresponding to the Eddington standard model of stellar structure.

- A polytrope with index n = 5 has an infinite radius. It corresponds to the simplest plausible model of a self-consistent stellar system, first studied by A. Schuster in 1883.

- A polytrope with index n = ∞ corresponds to what is called an isothermal sphere, that is an isothermal self-gravitating sphere of gas, whose structure is identical to the structure of a collisionless system of stars like a globular cluster.

In general as the polytropic index increases, the density distribution is more heavily weighted toward the center (r = 0) of the body.

References

- ↑ Horedt, G.P. (2004). Polytropes. Applications in Astrophysics and Related Fields, Dordrecht : Kluwer. ISBN 1-4020-2350-2

- ↑ Weppner, S. P., McKelvey, J. P., Thielen, K. D. and Zielinski, A. K., "A variable polytrope index applied to planet and material models", "Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society", Vol. 452, No. 2 (Sept. 2015), pages 1375–1393, Oxford University Press also found at the arXiv

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, S. [ 1939 ] ( 1958 ). An Introduction to the Study of Stellar Structure, New York : Dover. ISBN 0-486-60413-6

- ↑ Hansen, C.J., Kawaler S.D. & Trimble V. ( 2004 ). Stellar Interiors - Physical Principles, Structure, and Evolution, New York : Springer. ISBN 0-387-20089-4