Polygonal fort

A polygonal fort is a type of fortification originating in Germany in the first half of the 19th century. Unlike earlier forts, polygonal forts had no bastions which had proved to be vulnerable, but were generally arranged in a ring around the place they were intended to protect, a ring fortress, so that each fort could mutually support their neighbours. The concept of the polygonal fort proved to be adaptable to improvements in the artillery which might be used against them and they continued to built and rebuilt well into the 20th century.

Bastion system deficiencies

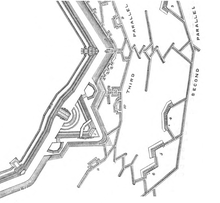

The bastion system of fortification had dominated military thinking since its introduction in 16th century Italy until the first decades of the 19th century. However, perhaps the greatest constructor of bastion forts, the French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, also devised an effective method to defeat them. Before Vauban, besiegers had driven a sap towards the enemy fort, until they reached the glacis, where artillery could be positioned to directly fire on the scarp wall, hoping to make a breach. Vauban's method was also to use saps, but using these to create three successive lines of entrenchments surrounding the fort, known as "parallels". The first two parallels reduced the vulnerability of the sapping work to a sally by the defenders, while the third parallel allowed the attackers to launch their attack from any point along its circumference. Vauban's final refinement was first used at the Siege of Ath in 1697, when he placed his artillery in the third parallel at a point close to the bastions, from where they could ricochet their shot along the inside of the parapet, dismounting the enemy guns and killing the defenders.[1] Other European engineers quickly adopted Vauban's three-parallel system, which became the standard method and would prove to be almost infallable.[2] Vauban himself devised three separate systems of fortification, each having a more elaborate system of outworks which were intended to prevent the besiegers from enfilading the bastions. Numerous other engineers followed during the next century, all attempting unsuccessfully to perfect the bastion system so as to nullify the Vauban-style of attack.[3] Furthermore, as the 18th century progressed, it was found that the continuous enceinte, or main defensive enclosure of a bastion fortress, could not be made large enough to accommodate the enormous field armies which were increasingly being employed in Europe, neither could the defences be constructed far enough away from the fortress town to protect the inhabitants from bombardment by the besiegers,[4] the range of whose guns was steadily increasing as better manufactured weapons were introduced.[5]

Theories of Montalembert and Carnot

Marc René, marquis de Montalembert (1714-1800), was a French commander who realised that the deficiencies of the bastion system demanded a radical revision. His envisaged system was intended to prevent the enemy from establishing their parallel entrenchments by an overwhelming artillery barrage from a large number of guns, which were to be protected from return fire. The elements of his system were the replacement of bastions with tenailles, resulting in a defensive line with a zigzag plan, allowing for the maximum number of guns to be brought to bear, and secondly, the provision of gun towers or redoubts (small forts), forward of the main line, each mounting a powerful artillery battery. All the guns were to be mounted in multi-storey masonry casemates, vaulted chambers built into the ramparts of the forts. Thirdly, defence of the ditches was to be by caponiers, covered galleries projecting into the ditch with numerous loopholes for small arms, compensating for the loss of the bastions with their flanking fire.[6] These three elements, Montalembert argued, would provde long-range offensive fire from the casemated main curtain, defence in depth from the detached forts or towers and close-in defence from the caponiers.[7] Montalembert described his theories in an eleven-volume work called La Fortification Perpendiculaire which was published in Paris between 1776 and 1778.[8] He summarised the benefits of his system thus; "...all is exposed to the fire of the besieged, which is everywhere superior to that of the besieger, and the latter cannot advance a step without being hit from all sides".[9]

A full realisation of Montalembert's ambitious plans for a great inland fortress was never attempted. However, almost immediately after publication, unofficial translations into German were being made of Montalembert's work and were being circulated amongst the officers of the Prussian Army. In 1780, Gerhard von Scharnhorst, a Hanoverian officer who went on to reform the Prussian Army, wrote that "All foreign experts in military and engineering affairs hail Montalembert's work as the most intelligent and distinguished achievement in fortification over the last hundred years. Things are very different in France". The conservative French military establishment was firmly wedded to the principles laid down by Vauban and improvements made by his later disciples, Louis de Cormontaigne and Charles Louis de Fourcroy. What little political influence the aristocratic Montalembert had during the Ancien Régime was lost following the French Revolution in 1792.[10]

However, in one field, Montalembert's work was allowed to take concrete form during his lifetime, that of coastal fortification. In 1778, he was commissioned to build a fort on the Île-d'Aix, defending the port of Rochefort, Charente-Maritime. The outbreak of the Anglo-French War forced him to hastily build his casemated fort from wood, however he was able to prove that his well-designed casemates were capable of operating without choking the gunners with smoke, one of the principle objections of his detractors.[11] The defences of the newly developed naval base at Cherbourg were later constructed according to his system.[12] After seeing Montalembert's coastal forts, American engineer Jonathan Williams acquired a translation of his book and took it to the United States,[13] where it inspired the Second and Third Systems of coastal fortification; the first fully developed example being Castle Williams in New York Harbor which was started in 1807.[14]

Lazare Carnot was an able French engineer officer, whose support for Montalembert had impeded his military career immediately after the Revolution. However, switching to politics, he was made Minister of War in 1800 and retired from public life two years later. In 1809, Napoleon I asked him to write a handbook for the commanders of fortresses, which was published in the following year under the title De la défense des places fortes.[15] While broadly supporting Montalembert and rejecting the bastion system, Carnot proposed that the attacker's preparations should be disrupted by massed infantry sorties, supported by a hail of high-angle fire from mortars and howitzers. Some of Carnot's innovations, such as the Carnot wall, a loopholed wall at the foot of the scarp face of the rampart to shelter defending infantry, would be widely used in later fortifications, but remained controversial.[16]

Prussian System

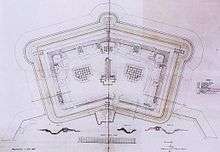

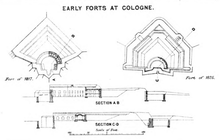

After the final fall of Napoleon I in 1815, the Congress of Vienna founded the German Confederation, an alliance of the numerous German states, dominated by the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire. Their immediate priority was the defence of the borders of the new alliance against France in the east and Russia in the west.[17] The Prussians started in the west by refortifying the fortress cities of Koblenz and Cologne (German: Köln), both important crossing points on the River Rhine, under the direction of Ernst Ludwig von Aster and assisted by Gustav von Rauch, both supporters of the Montalembert system.[18] Clearly influenced by Montalembert and Carnot, the novel feature of these new works was that they were encircled by forts, each several hundred metres out from the original enciente, carefully sited so as to make best use of the terrain and to be capable of mutually supporting the neighbouring forts.[19] This established the principle of the ring fortress or girdle fortress which characterised the new system. The detached forts were polygons of four or five sides in plan, with the front faces of the rampart angled at 95°. The rear or gorge of the fort was closed with a masonry wall, sufficient to repel a surprise infantry attack, but easily demolished by the defenders' artillery should the fort be captured by the attackers. In the centre of the gorge wall was a reduit or keep, provided with casemates for guns which could fire over the rampart or along the flanks to support the next forts in the chain.[20] The original bastioned encientes of these fortresses were initially retained or even rebuilt so as to prevent an attacker from infiltrating between the outlying forts and taking the fortress by a coup de main. However, it was later thought by some engineers that a simple entrenchment would suffice or that no inner defence was necessary; the issue remained a debating point for some decades.[21] In any case, few European cities undergoing the rapid expansion caused by the Industrial Revolution would willingly accept the restriction to their growth caused by a continuous line of ramparts.[22]

Aster insisted that his new technique was "not to be regarded... as a particular system" but this type of ring fortress became known as the Prussian System. Austrian engineers adopted a similar approach although differing in some details; the Prussian System and the Austrian System were together known as the German System.[23]

Lessons of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and Sardinia. Russian fortifications, which included some modern advances, were tested against the latest British and French artillery. At Sevastopol itself, the main focus of the allied effort, the Russians had planned a modern fortress, but little work had been done and earthworks were rapidly constructed instead. The largest and most complex earthwork, the Great Redan, was found to be largely resistant to British bombardments and difficult to carry by assault. Only one stone casemated work, the Malakoff Tower, had been completed at the time of the allied landing and proved impervious to bombardment, but was finally carried by a coup de main by French infantry.[24] Elsewhere, in the Battle of Kinburn (1855), an Anglo-French fleet undertook a bombardment of the Russian fortress which guarded the mouth of the Dnieper River. The most successful weapon there was the Paixhans gun which was mounted on ironclad floating batteries. These guns were the first to be able to fire explosive shells on a low trajectory, and were able to devastate the open ramparts of the forts, causing their surrender within four hours. British attempts to subdue the casemated Russian forts at Kronstadt and other fortifications in the Baltic Sea using conventional naval guns were far less successful.[25]

Impact of rifled artillery

The first rifled artillery designs were developed independently during the 1840s and 1850s by several engineers in Europe. These weapons offered greatly increased range, accuracy and penetrating power over their smooth-bore guns then in use.[26] The first effective use of rifled guns was during the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859, when the French used them against the Austrians. The Austrians quickly realised that the outlying forts of their ring fortresses were now too close-in to prevent an enemy from bombarding a besieged town, and at Verona, they added a second circle of forts, about a mile (1.6 km) forward of the existing ring.[27]

At that time, the British were concerned about a French invasion and in 1859 appointed the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom to fortify the naval dockyards of southern England. The experts on the commission, led by Sir William Jervois, interviewed Sir William Armstrong, a major developer and manufacturer of rifled artillery, and were able to incorporate his advice into their designs.[28] The ring fortresses at Plymouth and Portsmouth were set further out than the Prussian designs they were based on, and the casemates of coastal batteries were protected by composite armoured shields, tested to be resistant to the latest heavy projectiles.[29]

In the United States, it had been decided at an early stage that it would be impractical to providing landward fortifications for their rapidly expanding cities, but a considerable investment had been made in seaward defences in the form of multi-tiered casemated batteries, originally based on Montalembert's designs. During the American Civil War of 1861 to 1865, the exposed masonry of these coastal batteries was found to be vulnerable to modern rifled artillery; Fort Pulaski, for example, was quickly breached by only ten of these guns. On the other hand, the hastily constructed earthworks of landward fortifications proved much more resilient; the garrison of Fort Wagner were able to hold out for 58 days behind ramparts built of sand.[30]

In France meanwhile, the military establishment clung to the concept of the bastion system. Between 1841 and 1844, an immense bastioned trace, the Thiers Wall, had been constructed encircling Paris. It was a single rampart 33 kilometres (21 miles) long reinforced by 94 bastions. The main approaches to the city were further defended by several outlying bastioned forts, designed for all-round defence but not sited to be mutually supporting. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the invading Prussians were able to surround Paris after taking some of the outer forts, and then bombard the city and its population with their rifled siege guns, without the need for a costly assault.[31] In the aftermath of defeat, the French belatedly adopted a version of the polygonal system in a huge programme of fortification which commenced in 1874 under the direction of General Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières. Polygonal forts typical of the Séré de Rivières system had guns protected by iron armour or revolving Mougin turrets. The vulnerable masonry of the accommodation casemates were built facing away from the enemy, protected overhead by large mounds of earth, 5.5 metres (18 feet) deep.[32] The programme involved building ring fortresses around Paris and to guard potential border crossing points, often surrounding Vauban-era fortifications; however, the loss of Alsace and Lorraine to the Prussians created the need for a new defensive zone. The whole scheme was described as a "barrier of iron".[33] Similar forts were also being built in Germany at that time, designed Hans Alexis von Bichler.[34]

The "torpedo-shell crisis"

From the mid-19th century, chemists produced the first high explosive compounds, as opposed to low explosives such as gunpowder. The first of these, nitroglycerine and from 1867, dynamite, proved to be too unstable to be fired from a gun without exploding in the barrel. However, 1885, the French chemist Eugène Turpin, patented a form of picric acid, which proved stable enough to be used as a blasting charge in artillery shells. These shells had recently evolved from the traditional sphere of iron into a pointed cylinder, at that time known as a "torpedo-shell". The combination of these, combined with new delayed-action fuses, meant that shells were now able to bury themselves deep under the surface of a fort and then explode with unprecedented force. The realisation that this new technology made even the most modern forts vulnerable, was known as the "torpedo-shell crisis". The great powers of continental Europe were therefore forced into vastly expensive programmes of building new fortifications and rebuilding existing ones, to designs that were calculated to counter this latest threat.[35]

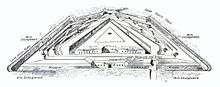

In France, the recently completed forts began to be refurbished, with thick layers of concrete reinforcing the ramparts and the rooves of magazines and accommodation spaces. The Belgians had not started their new fortifications when the effectiveness of the new munitions became known and their chief engineer, Henri Alexis Brialmont, was able to incorporate countermeasures in his design.[36] Brialmont's forts were triangular in plan,[37] and made extensive use of concrete with the main armament mounted in rotating turrets connected by tunnels. Both the French and Belgians assumed that the siege guns which their forts would need to withstand would not exceed a calibre of 21 centimetres (8 inches), as this was the largest mobile weapon in use at that time.[38]

In Germany, after updating their Bichler forts with layers of sand and concrete and building others in the style of Brialmont, a new design emerged, in which a fort's artillery and infantry positions would be dispersed in the landscape, connected only by trenches or tunnels and without a continuous enciente. This type of fortified position was called a feste; it was the end result of the work of several German theorists, but came to fruition under Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz who was appointed Inspector-General of Fortifications in 1898.[39]

World Wars

At the start of the First World War in August 1914, the German Army crossed into neutral Belgium with the object of outflanking the French border fortifications. In their path was the fortified position of Liège, a ring fortress built by Brialmont with a circumference of 46 km (28.5 mi), which the Germans reached on 4 August. Repeated attempts to pass massed infantry through the intervals between the forts, resulted in the capture of the city of Liège itself on 7 August, at the cost of 47,500 German casualties, but without any of the forts being taken.[40] These were only subdued by the arrival of super-heavy 42 cm Gamma Mörser siege howitzers and other large weapons, which were capable of smashing the armoured turrets and penetrating the concrete living spaces; the last fort surrendering on 16 August.[41] The fortress at Namur was demolished in the same fashion a few days later and that at Antwerp only survived for longer because fewer resources were directed against it.[42] On the Eastern Front, the forts of Russia and Romania were also quickly overcome by German and Austrian heavy artillery. These results led the French high command to the conclusion that fixed fortifications were obsolete and they began the process of disarming their forts, since there was a grave shortage of medium artillery pieces in their field armies.[43] In February 1916, the Germans launched an attack on the ring fortress at Verdun, hoping to force the French to squander their forces in costly counter-attacks in an effort to regain it. They found that the Verdun forts, which had been recently upgraded with extra layers of concrete and sand, were resistant to their heaviest shells. Although initially Fort Douaumont was captured almost accidentally by a small party of Germans who climbed through an unattended embrasure, the rest of the forts could not be permanently subdued and the offensive was eventually called off in December after huge casualties on both sides.[44]

After the war, the apparent success of the Verdun forts led the French government to invest heavily in the re-fortification of their eastern borders. However, rather than build new polygonal forts, the method chosen was a developed version of the German feste system of dispersed strongpoints interconnected by tunnels to a central underground barracks, all concealed in the landscape. This concept known to the French as fort palmé because the elements of the fort were analogous to the fingers of a hand.[45] The resultant system of fortifications eventually became known as the Maginot Line after the French Minister of War who had initiated the project in 1930. Where the Maginot Line coincided with existing Séré de Rivières forts, new concrete casemates were constructed inside the old works.[46] In Belgium, a series of commissions decided that a new line of fortifications should be constructed at Liège, while some of the old forts there should be modernised. Three new forts were constructed which were developed forms of the old Brialmont polygonal forts. The fourth and largest, Fort Eben-Emael, had its enciente defined by the great cutting of the Albert Canal.[47]

On 10 May 1940, German forces attacked the new Belgian forts, quickly neutralising Eben-Emael by airborne assault. The three other forts were bombarded by 305 mm howitzers and dive-bombers, and each repulsed several infantry assaults. Two of the forts surrendered on 21 May and the last, Fort de Battice, on the day after, having been by-passed by the main German thrust.[48] Modernised French polygonal forts at Maubeuge were attacked on 19 May and were surrendered after their gun turrets and observation domes had been knocked out with anti-tank guns and demolition charges.[46] Late in the war, the ring fortress at Metz was hastily prepared for defence by German forces and was attacked by the U.S. Third Army in mid-September 1944 in the Battle of Metz; the last fort finally surrendered nearly three months later.[49]

References

- ↑ Hogg, pp. 51-52

- ↑ Ostwald, p. 12

- ↑ Duffy, p. 41

- ↑ Royal Military Academy p. 143

- ↑ Hogg p. 73

- ↑ Wade, p. 110

- ↑ Duffy p. 160

- ↑ Wade, p. 110

- ↑ Lloyd & Marsh, p. 114

- ↑ Duffy p. 163

- ↑ Lloyd & Marsh, pp. 125-127

- ↑ Lepage p. 96

- ↑ Wade p. 111

- ↑ Hogg p. 78

- ↑ Royal Military Academy pp. 127-128

- ↑ Lepage pp. 147-148

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann p. 7

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann p. 9

- ↑ Douglas, p. 126

- ↑ Royal Military Academy pp. 132-133

- ↑ Kenyon, p. 3

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 98

- ↑ Royal Military Academy p. 132

- ↑ Hogg pp. 79-81

- ↑ Hogg, pp. 80-82

- ↑ Kinard, p. 222

- ↑ Royal Military Academy, p. 150

- ↑ Crick 2012, pp. 46-47

- ↑ Dyer 2003, p. 7

- ↑ Hogg, p. 101

- ↑ Hogg, p. 102

- ↑ Hogg, p. 104

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann (Neutral States), p. xiii

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann (Central States), p. 47

- ↑ Donnel, pp. 7-8

- ↑ Donnel, p. 8

- ↑ Donnel, p. 12

- ↑ Hogg, pp. 103-105

- ↑ Kaufmann and Kaufmann (Central States), pp. 30-31

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann (Neutral States), pp. 94

- ↑ Hogg, pp. 118-119

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann (Neutral States), p. 94

- ↑ Hogg, p. 121

- ↑ Hogg, pp. 121-122

- ↑ Kaufmann & Kaufmann (Fortress France), p. 14

- 1 2 Kaufmann, Kaufmann & Lang, p. 208

- ↑ Dunstan (Introduction)

- ↑ Kauffmann (Fortress Europe), pp. 116-117

- ↑ Zaloga, p. 70

Sources

- Crick, Timothy (2012). Ramparts of Empire: The Fortications of Sir William Jervois, Royal Engineer 1821-1897. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-1-905816-04-0.

- Donnel, Clayton (2013). Breaking the Fortress Line 1914. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-813-9.

- Donnel, Clayton (2011). The Fortifications of Verdun 1874–1917. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-412-3.

- Douglas, Howard (1859). Observations on Modern Systems of Fortification. London: John Murray.

- Duffy, Christopher (2017). The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great 1660-1789. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-92464-2.

- Dunstan, Simon (2005). Fort Eben Emael: The key to Hitler’s victory in the West. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-821-2.

- Dyer, Nick (2003). British Fortification in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The Palmerston Forts Society. ISBN 978-0-9523634-6-0.

- Hogg, Ian V. (1975). Fortress: A History of Military Defence. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 0-356-08122-2.

- Kinard, Jeff (2007). Artillery: An Illustrated History of Its Impact. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Inc. ISBN 978-1-85109-556-8.

- Kaufmann, J.E. (1999). Fortress Europe: European Fortifications Of World War II. Combined Publishing,U.S. ISBN 978-1-58097-000-6.

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W. (2008). Fortress France: The Maginot Line and French Defenses in World War II. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3395-3.

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W. (2014). The Forts and Fortifications of Europe 1815-1945 - The Central States: Germany, Austria-Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-806-1.

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W. (2014). The Forts and Fortifications of Europe 1815-1945 - The Neutral States. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-392-3.

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W. (2016). Verdun 1916: The Renaissance of the Fortress. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-4738-2702-8.

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W.; Lang, Patrice. The Maginot Line: History and Guide. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-068-3.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (2010). French Fortifications, 1715–1815: An Illustrated History. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-4477-9.

- Lloyd, E.M. (1887). Vauban, Montalembert, Carnot: Engineer Studies. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Mahan, D.H. (1898). Mahan's Permanent Fortifications. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Oswald, James (2007). Vauban Under Siege: Engineering Efficiency and Martial Vigor in the War of the Spanish Succession. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-15489-6.

- Royal Military Academy, Woolwich (1893). Text Book of Fortification and Military Engineering: Part II. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers. McLean VA: Coast Defense Study Group (CDSG) Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

- Ward, Bernard Rowland (Major R. E.) (1901). Notes on Fortification: With a Synoptical Chart. London: John Murray.

- Zaloga, Steven J. Metz 1944: Patton’s Fortified Nemesis. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-591-5.