Estrous cycle

The estrous cycle or oestrus cycle (derived from Latin oestrus 'frenzy', originally from Greek οἶστρος oîstros 'gadfly') is the recurring physiological changes that are induced by reproductive hormones in most mammalian therian females. Estrous cycles start after sexual maturity in females and are interrupted by anestrous phases or by pregnancies. Typically, estrous cycles continue until death. Some animals may display bloody vaginal discharge, often mistaken for menstruation.

Differences from the menstrual cycle

Mammals share the same reproductive system, including the regulatory hypothalamic system that produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone in pulses, the pituitary gland that secretes follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, and the ovary itself that releases sex hormones including estrogens and progesterone.

However, species vary significantly in the detailed functioning. One difference is that animals that have estrous cycles resorb the endometrium if conception does not occur during that cycle. Animals that have menstrual cycles shed the endometrium through menstruation instead. Another difference is sexual activity. In species with estrous cycles, females are generally only sexually active during the estrus (oestrus) phase of their cycle . This is also referred to as being "in heat". In contrast, females of species with menstrual cycles can be sexually active at any time in their cycle, even when they are not about to ovulate.

Humans have menstrual cycles rather than estrous cycles. They, unlike most other species, have concealed ovulation, a lack of obvious external signs to signal estral receptivity at ovulation (i.e., the ability to become pregnant). There are, however, subtle signs to which human males may favorably respond, including changes in a woman's scent[1] and facial appearance.[2] Some research also suggests that women tend to have more sexual thoughts and are more prone to sexual activity right before ovulation.[3][4] Animals with estrous cycles often have unmistakable outward displays of receptivity, ranging from engorged and colorful genitals to behavioral changes like mating calls.

Etymology and nomenclature

Estrus is derived via Latin oestrus ('frenzy', 'gadfly'), from Greek οἶστρος oîstros (literally 'gadfly', more figuratively 'frenzy', 'madness', among other meanings like 'breeze'). Specifically, this refers to the gadfly in Ancient Greek mythology that Hera sent to torment Io, who had been won in her heifer form by Zeus. Euripides used oestrus to indicate 'frenzy', and to describe madness. Homer uses the word to describe panic.[5] Plato also uses it to refer to an irrational drive[6] and to describe the soul "driven and drawn by the gadfly of desire".[7] Somewhat more closely aligned to current meaning and usage of estrus, Herodotus (Histories, ch. 93.1) uses oîstros to describe the desire of fish to spawn.[8]

The earliest use in English was with a meaning of 'frenzied passion'. In 1900, it was first used to describe 'rut in animals; heat'.[9][10]

In British and most Commonwealth English, the spelling is oestrus or (rarely) œstrus. In all English spellings, the noun ends in -us and the adjective in -ous. Thus in North American English, a mammal may be described as "in estrus" when it is in that particular part of the estrous cycle.

Four phases

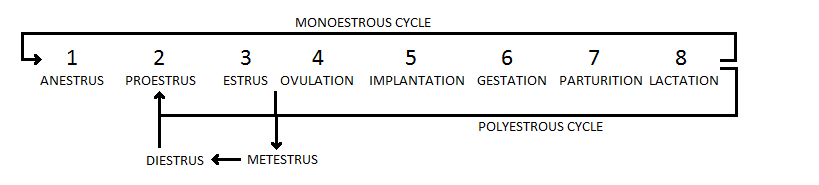

A four-phase terminology is used in reference to animals with estrous cycles.

Proestrus

One or several follicles of the ovary start to grow. Their number is species specific. Typically this phase can last as little as one day or as long as three weeks, depending on the species. Under the influence of estrogen the lining in the uterus (endometrium) starts to develop. Some animals may experience vaginal secretions that could be bloody. The female is not yet sexually receptive; the old corpus luteum gets degenerated; the uterus and the vagina get distended and filled with fluid, become contractile and secrete a sanguinous fluid; the vaginal epithelium proliferates and the vaginal smear shows a large number of non-cornified nucleated epithelial cells. Variant terms for proestrus include pro-oestrus, proestrum, and pro-oestrum.

Estrus

Estrus or oestrus refers to the phase when the female is sexually receptive ("in heat"). Under regulation by gonadotropic hormones, ovarian follicles mature and estrogen secretions exert their biggest influence. The female then exhibits sexually receptive behavior,[4] a situation that may be signaled by visible physiologic changes. Estrus is commonly seen in the mammalian species, including primates. It is thought that this increased sexual receptivity serves the function of helping the female obtain mates with superior genetic quality.[4] This phase is sometimes called estrum or oestrum.

In some species, the labia are reddened. Ovulation may occur spontaneously in some species. Especially among quadrupeds, a signal trait of estrus is the lordosis reflex, in which the animal spontaneously elevates her hindquarters.

Metestrus or diestrus

This phase is characterized by the activity of the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. The signs of estrogen stimulation subside and the corpus luteum starts to form. The uterine lining begins to appear. In the absence of pregnancy the diestrus phase (also termed pseudo-pregnancy) terminates with the regression of the corpus luteum. The lining in the uterus is not shed, but is reorganized for the next cycle. Other spellings include metoestrus, metestrum, metoestrum, dioestrus, diestrum, and dioestrum.

Anestrus

Anestrus refers to the phase when the sexual cycle rests. This is typically a seasonal event and controlled by light exposure through the pineal gland that releases melatonin. Melatonin may repress stimulation of reproduction in long-day breeders and stimulate reproduction in short-day breeders. Melatonin is thought to act by regulating the hypothalamic pulse activity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Anestrus is induced by time of year, pregnancy, lactation, significant illness, chronic energy deficit, and possibly age. Chronic exposure to anabolic steroids may also induce a persistent anestrus due to negative feedback on the hypothalamus/ pituitary/ gonadal axis. Other spellings include anoestrus, anestrum, and anoestrum.

After completion (or abortion) of a pregnancy, some species have postpartum estrus, which is ovulation and corpus luteum production that occurs immediately following the birth of the young.[11] For example, the mouse has a fertile postpartum estrus that occurs 14 to 24 hours following parturition.

Terminology for humans

In a medical context, human ovulation is uncommonly also referred to as estrus or oestrus, with the non-ovulating range of the menstrual cycle sometimes generally referred to as the luteal phase.[4] A more complex classification of the menstrual cycle includes two major sub-cycles with three phases each: the ovarian cycle, with the follicular, ovulation (= estrus), and luteal phases; and the uterine cycle, with the menstruation (or menses), proliferative, and secretory phases.

Cycle variability

Estrous cycle variability differs among species, but cycles are typically more frequent in smaller animals. Even within species significant variability can be observed, thus cats may undergo an estrous cycle of 3 to 7 weeks. Domestication can affect estrous cycles due to changes in the environment.

Frequency

Some species, such as cats, cows and domestic pigs, are polyestrous, meaning that they can go into heat several times per year. Seasonally polyestrous animals or seasonal breeders have more than one estrous cycle during a specific time of the year and can be divided into short-day and long-day breeders:

- Short-day breeders, such as sheep, goats, deer and elk are sexually active in fall or winter.

- Long-day breeders, such as horses, hamsters and ferrets are sexually active in spring and summer.

Species that go into heat twice per year are diestrous.

Monoestrous species, such as bears, foxes, and wolves, have only one breeding season per year, typically in spring to allow growth of the offspring during the warm season to aid survival during the next winter.

A few mammalian species, such as rabbits, do not have an estrous cycle and are able to conceive at almost any arbitrary moment (comparable with humans, who, however, have a menstrual cycle in place of an estrous cycle).

Generally speaking, the timing of estrus is coordinated with seasonal availability of food and other circumstances such as migration, predation etc., the goal being to maximize the offspring's chances of survival. Some species are able to modify their estral timing in response to external conditions.

Specific species

Cats

The female cat in heat has an estrus of 14 to 21 days and is generally characterized as an induced ovulator, in that coitus induces ovulation. However, various incidents of spontaneous ovulation have been documented in the domestic cat and various non-domestic species.[12] Without ovulation, she may enter interestrus before reentering estrus. With the induction of ovulation, the female becomes pregnant or undergoes a non-pregnant luteal phase, also known as pseudopregnancy. Cats are polyestrous but experience a seasonal anestrus in autumn and late winter.[13]

Dogs

A female dog is usually diestrous (goes into heat typically twice per year), although some breeds typically have one or three cycles per year. The proestrus is relatively long at 5 to 9 days, while the estrus may last 4 to 13 days, with a diestrus of 60 days followed by about 90 to 150 days of anestrus. Female dogs bleed during estrus, which usually lasts from 7–13 days, depending on the size and maturity of the dog. Ovulation occurs 24–48 hours after the luteinizing hormone peak, which is about somewhere around the fourth day of estrus; therefore, this is the best time to begin breeding. Proestrus bleeding in dogs is common and is believed to be caused by diapedesis of red blood cells from the blood vessels due to the increase of the estradiol-17β hormone.[14]

Horses

A mare may be 4 to 10 days in heat and about 14 days in diestrus. Thus a cycle may be short, around 3 weeks. Horses mate in spring and summer, autumn is a transition time, and anestrus rules the winter.

A feature of the fertility cycle of horses and other large herd animals is that it is usually affected by the seasons. The number of hours daily that light enters the eye of the animal affects the brain, which governs the release of certain precursors and hormones. When daylight hours are few, these animals "shut down", become anestrous, and do not become fertile. As the days grow longer, the longer periods of daylight cause the hormones that activate the breeding cycle to be released. As it happens, this benefits these animals in that, given a gestation period of about eleven months, it prevents them from having young when the cold of winter would make their survival risky.

Rats

Rats typically have rapid cycle times of 4 to 5 days. Although they ovulate spontaneously, they do not develop a fully functioning corpus luteum unless they receive coital stimulation. Fertile mating leads to pregnancy in this way, but infertile mating leads to a state of pseudopregnancy lasting about 10 days. Mice and hamsters have similar behaviour.[15] The events of the cycle are strongly influenced by lighting periodicity.[9]

A set of follicles starts to develop near the end of proestrus and grows at a nearly constant rate until the beginning of the subsequent estrus when the growth rates accelerate eightfold. Ovulation occurs about 109 hours after the start of follicle growth.

Oestrogen peaks at about 11 am on the day of proestrus. Between then and midnight there is a surge in progesterone, luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, and ovulation occurs at about 4 am on the next, estrus day. The following day, metestrus, is called early diestrus or diestrus I by some authors. During this day the corpora lutea grow to a maximal volume, achieved within 24 hours of ovulation. They remain at that size for three days, halve in size before the metestrus of the next cycle and then shrink abruptly before estrus of the cycle after that. Thus the ovaries of cycling rats contain three different sets of corpora lutea at different phases of development.[16]

Bison

Buffalo have an estrous cycle of about 22 to 24 days. Buffalo are known for difficult estrous detection. This is one major reason for being less productive than cattle. During four phases of its estrous cycle, mean weight of corpus luteum has been found to be 1.23±0.22 (metestrus), 3.15±0.10 (early diestrus), 2.25±0.32 (late diestrus), and 1.89±0.31g (proestrus/estrus), respectively. The plasma progesterone concentration was 1.68±0.37, 4.29±0.22, 3.89±0.33, and 0.34±0.14 ng/ml while mean vascular density (mean number of vessels/10 microscopic fields at 400x) in corpus luteum was 6.33±0.99, 18.00±0.86, 11.50±0.76, and 2.83±0.60 during the metestrus, early diestrus, late diestrus and proestrus/estrus, respectively.[17]

Others

Estrus frequencies of some other mammals:

See also

References

- ↑ Kuukasjärvi, Seppo; Eriksson, C. J. Peter; Koskela, Esa; Mappes, Tapio; Nissinen, Kari; Rantala, Markus J. (1 July 2004). "Attractiveness of women's body odors over the menstrual cycle: the role of oral contraceptives and receiver sex". Behavioral Ecology. 15 (4): 579–584. doi:10.1093/beheco/arh050.

- ↑ Roberts, S. C.; Havlicek, J.; Flegr, J.; Hruskova, M.; Little, A. C.; Jones, B. C.; Perrett, D. I.; Petrie, M. (7 August 2004). "Female facial attractiveness increases during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271: S270–S272. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0174. PMC 1810066.

- ↑ Bullivant, Susan B.; Sellergren, Sarah A.; Stern, Kathleen; Spencer, Natasha; Jacob, Suma; Mennella, Julie; McClintock, Martha (February 2004). "Women's sexual experience during the menstrual cycle: Identification of the sexual phase by noninvasive measurement of luteinizing hormone". Journal of Sex Research. 41 (1): 82–93. doi:10.1080/00224490409552216. PMID 15216427.

- 1 2 3 4 Geoffrey Miller (April 2007). "Ovulatory cycle effects on tip earnings by lap dancers: Economic evidence for human estrus?" (PDF). Evolution and Human Behavior (28): 375–381.

- ↑ Panic of the suitors in Homer, Odyssey, book 22

- ↑ Plato, Laws, 854b

- ↑ Plato, The Republic

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories, ch. 93.1

- 1 2 Freeman, Marc E. (1994). "The Neuroendocrine control of the ovarian cycle of the rat". In Knobil, E.; Neill, J. D. The Physiology of Reproduction. 2 (2nd ed.). Raven Press.

- ↑ Heape, W. (1900). "The 'sexual season' of mammals and the relation of the 'pro-oestrum' to menstruation'". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. NCBI. 44: 1:70.

- ↑ medilexicon.com > postpartum estrus citing: Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Copyright 2006

- ↑ Pelican et al., 2006

- ↑ Spindler and Wildt, 1999

- ↑ Walter, I.; Galabova, G.; Dimov, D.; Helmreich, M. (February 2011). "The morphological basis of proestrus endometrial bleeding in canines". Theriogenology. 75 (3): 411–420. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.04.022. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ↑ McCracken, J. A.; Custer, E. E.; Lamsa, J. C. (1999). "Luteolysis: A neuroendocrine-mediated event". Physiological Reviews. 79 (2): 263–323. doi:10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.263. PMID 10221982.

- ↑ Yoshinaga, K. (1973). "Gonadotrophin-induced hormone secretion and structural changes in the ovary during the nonpregnant reproductive cycle". Handbook of Physiology. Endocrinology II, Part 1.

- ↑ Qureshi, A. S.; Hussain, M.; Rehan, S.; Akbar, Z.; Rehman, N. U. (2015). "Morphometric and angiogenic changes in the corpus luteum of nili-ravi buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) during estrous cycle". Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 52 (3): 795–800.

Further reading

- Spindler, R. E.; Wildt, D. E. (1999). "Circannual variations in intraovarian oocyte but not epididymal sperm quality in the domestic cat". Biology of Reproduction. 61: 188–194. doi:10.1095/biolreprod61.1.188.

- Pelican, K.; Wildt, D.; Pukazhenthi, B.; Howard, J. G. (2006). "Ovarian control for assisted reproduction in the domestic cat and wild felids". Theriogenology. 66: 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.03.013.

External links

- Systematic overview

- Etymology

- Cat estrous cycle

- Horse estrous cycle

- Skloot, Rebecca (December 9, 2007). "Lap-dance Science". The New York Times Magazine.