Bojagi

| Bojagi | |

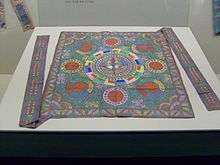

_MET_DP158238.jpg) Silk patchwork Bojagi from the collection of the Met | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 보자기 |

| Hanja | 褓 |

| Revised Romanization | bojagi |

| McCune–Reischauer | pojagi |

A bojagi (Hangul: 보자기; MR: pojagi, sometimes shortened to 보; bo; po) is a traditional Korean wrapping cloth. Bojagi are typically square and can be made from a variety of materials, though silk or ramie are common. Embroidered bojagi are known as subo, while patchwork or scrap bojagi are known as chogak bo.

Bojagi have many uses, including as gift wrapping, in weddings, and in Buddhist rites. More recently, they have been recognized as a traditional art form, often featured in museums and inspiring modern reinterpretations.

History

Traditional Korean folk religions believed that keeping something wrapped protected good luck.[1] It is believed that the earliest use of the wrappings dates to the Three Kingdoms Period, but no examples survive from this period.[2]

The earliest surviving examples, from the early Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), were used in a Buddhist context, as tablecloths or coverings for sutras. The cloths particularly marked special events, such as weddings or betrothals, where the use of a new cloth was believed to convey "an individual's concern for that which was being wrapped, as well as respect for its recipient." For a royal wedding, up to 1,650 bojagi might be created.[2]

Everyday use of bojagi declined in the 1950s, and they were not treated by Koreans as art objects until the late 1960s.[2][3] In 1997, the "Korean Beauty" postage stamp series included four stamps featuring bojagi.[4]

Physical characteristics

Traditionally, the bojagi is a square, measuring from one p'ok in width (approximately 35 cm), for small items, to ten p'ok for larger objects such as bedding.[5] Materials included silk, ramie, and hemp.

Royal bojagi (kung-bo)

Royal wrapping cloths were known as kung-bo.[5] Within the Joseon royal court the preferred fabric in bojagi construction was domestically produced pink-red to purple cloth.[6] These fabrics were often painted with designs, such as dragons.[2]

Unlike the used and re-used frugality of non-royal wrapping cloths, hundreds of new bojagi were commissioned on special occasions such as royal birthdays and New Year’s Day.[2]

Common bojagi (min-bo or chogak bo)

Min-bo or chogak bo (조각보) were "patchwork" bojagi made by commoners.[7] In contrast with the royal kung-bo, which were not patchwork,[2] these cloths were created from small segments ("chogak") of fabric from other sewing, such as those left over from cutting the curves in traditional hanbok clothing.[3] Both symmetrical 'regular' and random-seeming 'irregular' patterned cloths were sewn, with styles presumably selected by an individual woman's aesthetic tastes.[2]

As food coverings

Chogak bo are closely associated with food coverings. The mid-19th century to early 20th century examples that have survived until the present day often have a small loop of ribbon attached in the centre of the square, to aid in lifting the cover away from food. Table-sized bojagi often have straps attached to the corners, so they can be fastened to the table, to secure items in place, when the table is moved.[6]

Different bojagi were used for covering different foods and at different seasons. While lightweight cloths helped air to circulate during summer, to keep food warm in winter bojagi could be padded and lined as well.[6] To prevent the bojagi from being dirtied from food, the underside is often lined with oiled paper.[2][6]

For carrying items

Bojagi were used for transporting items, as well as covering, or keeping things together in storage. One such example is a 'knapsack' arrangement, where the cloth is wrapped and tied so that items can be securely transported upon ones' back.

Embroidered bojagi

Embroidered bojagi, also called subo (수보) (the prefix su means embroidery), was another form of decorated cloth. A common ornament was that of stylized trees, varying in style from 'naive',[7] to detailed depictions of flowers, fruits, birds and symbols of good luck.[8][9] These cloths are closely associated with joyous occasions such as betrothals and weddings,[2] used to wrap items such as gifts from the family of the bridegroom to the new bride, and the symbolic wooden wedding geese.[10]

The embroidery was done with spun thread, on a cotton or silk ground. The subo fabric was then lined, and possibly padded.[2]

Modern references and exhibitions

The Museum of Korean Embroidery in Seoul has a collection of 1,500 pieces of bojagi, with a particular focus on chogak bo.[3] Museum collections outside of Korea, including in Kyoto,[11] London,[12] San Francisco,[13] and Los Angeles,[14] also contain bojagi.

The patchwork style of the chogak bo have inspired artists working in other media, such as clothing designers Lee Chunghie[12][15] and Karl Lagerfeld.[16] The facade of the flagship store of French jeweler Cartier in Cheongdam-dong is also reportedly inspired by the craft.[17] Japanese embroiderers have also worked in the style.[11]

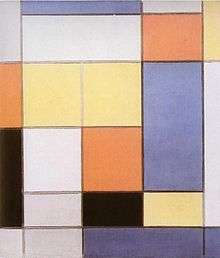

The patterns of chogak bo have been compared to the work of Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian.[2][3][7]

See also

References

- ↑ Korean Culture and Information Service Ministry of Culture (2010). Guide to Korean Culture. Hollym Corp. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-56591-287-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (2004-01-01). "A Celebration of Life: Patchwork and Embroidered Pagoji by Unknown Korean Women". Creative Women of Korea: The Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Centuries. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765611895.

- 1 2 3 4 "Beauty of 'jogakbo' rediscovered". Korea Times. 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "South Korea Stamps 1997". 2004-08-09. Archived from the original on 2004-08-09. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- 1 2 Kim, Keumja Paik "Profusion of Colour: Korean Costumes and Wrapping Clothes of the Chosŏn Dynasty" in Julia M. White and Huh Dong-hwa [eds.] Wrappings of Happiness: A Traditional Korean Art Form (Honolulu Academy of Arts Publishing: 2003)

- 1 2 3 4 Huh Dong-hwa "History and Art in Traditional Wrapping Cloths" in Julia M. White and Huh Dong-hwa [eds.] Wrappings of Happiness: A Traditional Korean Art Form (Honolulu Academy of Arts Publishing: 2003) pp. 20–24

- 1 2 3 Gowman, Philip (2009-02-28). "Mudang and minhwa: It's a wrap". London Korean Links. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ Framed Royal Purple Wrapping Cloth with Peacocks Korean Art and Antiques

- ↑ "보자기" [Our Traditional Cloths] (in Korean). 2011-07-22. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ Lee, Patricia (2009). The Wrapping Scarf Revolution: The Earth-friendly Idea that Will Change the Way You Think about Your World. Leisure Arts. p. 18. ISBN 9781574861068.

- 1 2 "'Bojagi' culturally links Korea, Japan". Korea Times. 2014-01-21. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- 1 2 "Lee Chunghie". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "Bojagi". Asian Art Museum. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "Bojagi: The Korean Wrapping Cloth". LACMA. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "SDA Members In Print: Chunghie Lee Publishes 'Bojagi & Beyond'". Surface Design Association. 2011-09-26. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "'Couture Korea' exhibit paints past, present, future of Korean fashion". The Daily Californian. 2017-11-06. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- ↑ Garcia, Cathy Rose A. (28 September 2008). "Cartier Opens Flagship Store in Cheongdam". Korea Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

External links

- Cloth, Color and Beyond: Korea Society Bojagi Podcast

- youngminlee.com Bojagi – Youngmin Lee's Korean Textile Works

- Bojagi at Asian Art Museum of San Francisco - includes video and several examples from the museum's collection