Pink Floyd – The Wall

| Pink Floyd – The Wall | |

|---|---|

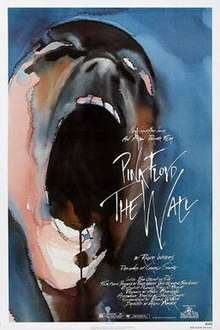

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Produced by | Alan Marshall |

| Screenplay by | Roger Waters |

| Based on |

The Wall by Pink Floyd |

| Starring | Bob Geldof |

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | Peter Biziou |

| Edited by | Gerry Hambling |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | MGM/UA Entertainment Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[2] |

| Box office | $22.2 million[3] |

Pink Floyd – The Wall is a 1982 British live-action/animated musical drama film directed by Alan Parker with animated segments by political cartoonist Gerald Scarfe, and is based on the 1979 Pink Floyd album of the same name. The film centers around a confined rocker named Pink, who, after being driven into insanity by the death of his father and many depressive moments during his lifetime, constructs a metaphorical (and sometimes physical) wall to be protected from the world and emotional situations around him. When this coping mechanism backfires he puts himself on trial and sets himself free. The screenplay was written by Pink Floyd vocalist and bassist Roger Waters.

Like its musical companion, the film is highly metaphorical, and symbolic imagery and sound are present most commonly. However, the film is mostly driven by music, and does not feature much dialogue. Gerald Scarfe drew and animated 15 minutes of animated sequences, which appear at several points in the film. It was the seventh animated feature to be presented in Dolby Stereo. The film is best known for its disturbing surrealism, animated sequences, sexual situations, violence and gore. Despite its turbulent production and the creators voicing their discontent about the final product, the film has since fared well generally, and has established cult status.

Plot

Pink is a rock star, one of several reasons behind his apparent depressive and detached emotional state. He is first seen in an unkempt hotel room, motionless and expressionless, watching television while the Vera Lynn recording of "The Little Boy that Santa Claus Forgot" plays. It is revealed that Pink's father, a British soldier, was killed in action during the Battle of Anzio during World War II, in Pink's infancy ("When The Tigers Broke Free, Part I"). The stampede of a modern rock concert is compared to soldiers running out of the foxholes to engage in combat ("In The Flesh?")

In a flashback, baby Pink is shown as "The Thin Ice" plays. Growing up during his childhood, Pink longs for a father figure ("Another Brick In The Wall, Part I"). He discovers a scroll from "kind old King George" and other relics from his father's military service and death ("When The Tigers Broke Free, Part II"). One item he finds, a bullet, is placed on the track of an oncoming train, where he sees non-descript people riding the train. At school, he is caught writing poems in class and humiliated by the teacher who reads a poem (part of verse 2 of the song "Money"). It is revealed that the teacher is verbally abusive to the students because his wife is verbally abusive to him ("The Happiest Days of Our Lives"). Young Pink imagines a surrealistically oppressive school system in which children fall into a meat grinder. The children then rise in rebellion and destroy the school, carrying the Teacher away to an unknown fate ("Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)"). Pink is also negatively affected by his overprotective mother ("Mother"). Such traumatic experiences are represented as "bricks" in the metaphorical wall he constructs around himself that divides him from society ("Empty Spaces").

As an adult, Pink eventually marries, but he and his wife soon grow apart. While he is in the United States on tour, Pink learns that his wife is having an affair ("Young Lust"). He turns to a willing groupie, whom he brings back to his hotel room only to trash it in a fit of violence, terrifying the groupie out of the room ("One Of My Turns"). After she leaves screaming, Pink goes into a deep depression ("Don't Leave Me Now"). After smashing the TV with his guitar, he vows that he doesn't need "anyone at all" ("Another Brick In The Wall, Part III"). With that, he mentally completes the wall that he started building to protect himself from being hurt ("Goodbye Cruel World").

Pink slowly begins to lose his mind to metaphorical "worms". He takes drugs and shaves all his body hair, cutting himself in the process, and, while watching The Dam Busters on television, morphs into a neo-Nazi alter-ego. Pink's manager, along with the hotel manager and some paramedics, discover Pink drugged out and unresponsive, so they inject him with adrenaline to enable him to perform ("Comfortably Numb")..

Pink fantasizes that he is a dictator and his concert is a neo-Nazi rally. Nazi-Pink holds a rally, and looks for people who are different, "queers", "coons", dopers, and orders them "against the wall". ("In The Flesh"). His followers proceed to attack ethnic minorities ("Run Like Hell"), and Pink holds a rally in suburban London ("Waiting for the Worms"). The scene is intercut with images of animated marching hammers that goose-step across ruins. Pink then stops hallucinating and screams "Stop!" He then takes refuge in the toilets at the concert venue, reciting poems.

In a climactic animated sequence, Pink, depicted as a small, almost inanimate rag doll, is on trial ("The Trial"), with his teacher, wife and mother as witnesses. His sentence is "to be exposed before [his] peers." The judge gives the order to "tear down the wall". Following a prolonged silence, the wall is smashed.

Several children are seen cleaning up a pile of debris after an earlier riot, with a freeze-frame on one of the children emptying a Molotov cocktail ("Outside The Wall").

Cast

- Bob Geldof as Pink

- Kevin McKeon as Young Pink

- David Bingham as Little Pink

- Christine Hargreaves as Pink's mother

- Eleanor David as Pink's wife

- Alex McAvoy as Teacher

- Bob Hoskins as Rock-and-roll manager

- Michael Ensign as Hotel manager

- James Laurenson as Pink's father

- Jenny Wright as American groupie

- Margery Mason as Teacher's wife

- Ellis Dale as English doctor

- James Hazeldine as Lover

- Ray Mort as Playground father

- Robert Bridges as American doctor

- Joanne Whalley, Nell Campbell, Emma Longfellow, and Lorna Barton as Groupies

- Philip Davis and Gary Olsen as Roadies

Production

Concept

In the mid-1970s, as Pink Floyd gained mainstream fame, Waters began feeling increasingly alienated from their audiences:

Audiences at those vast concerts are there for an excitement which, I think, has to do with the love of success. When a band or a person becomes an idol, it can have to do with the success that that person manifests, not the quality of work he produces. You don't become a fanatic because somebody's work is good, you become a fanatic to be touched vicariously by their glamour and fame. Stars—film stars, rock 'n' roll stars—represent, in myth anyway, the life as we'd all like to live it. They seem at the very centre of life. And that's why audiences still spend large sums of money at concerts where they are a long, long way from the stage, where they are often very uncomfortable, and where the sound is often very bad.[4]

Waters was also dismayed by the "executive approach", which was only about success, not even attempting to get acquainted with the actual persons of whom the band was comprised (addressed in an earlier song from Wish You Were Here, "Have a Cigar"). The concept of the wall, along with the decision to name the lead character "Pink", partly grew out of that approach, combined with the issue of the growing alienation between the band and their fans.[5] This symbolised a new era for rock bands, as Pink Floyd "explored (... ) the hard realities of 'being where we are'", drawing upon existentialists, namely Jean-Paul Sartre.[6]

Development

Even before the original Pink Floyd album was recorded, a film was intended to be made from it.[7] However, the concept of the film was intended to be live footage from the album's tour, with Scarfe's animation and extra scenes.[8] The film was going to star Waters himself.[8] EMI did not intend to make the film, as they did not understand the concept.[9]

Director Alan Parker, a Pink Floyd fan, asked EMI whether The Wall could be adapted to film. EMI suggested that Parker talk to Waters, who had asked Parker to direct the film. Parker instead suggested that he produce it and give the directing task to Gerald Scarfe and Michael Seresin, a cinematographer.[10] Waters began work on the film's screenplay after studying scriptwriting books. He and Scarfe produced a special-edition book containing the screenplay and art to pitch the project to investors. While the book depicted Waters in the role of Pink, after screen tests, he was removed from the starring role[11] and replaced with punk musician and frontman of the Boomtown Rats, Bob Geldof.[8] In Behind the Wall, both Waters and Geldof later admitted to a story during casting where Geldof and his manager took a taxi to an airport, and Geldof's manager pitched the role to the singer, who continued to reject the offer and express his contempt for the project throughout the fare, unaware that the taxi driver was Waters' brother, who promptly proceeded to tell Waters about Geldof's opinion.

Since Waters was no longer in the starring role, it no longer made sense for the feature to include Pink Floyd footage, so the live film aspect was dropped.[12] The footage culled from the five Wall concerts at Earl's Court from 13–17 June 1981 that were held specifically for filming was deemed unusable also for technical reasons as the fast Panavision lenses needed for the low light levels turned out to have insufficient resolution for the movie screen. Complex parts such as "Hey You" still had not been properly shot by the end of the live shows.[13] Parker also managed to convince Waters and Scarfe that the concert footage was too theatrical and that it would jar with the animation and stage live action. After the concert footage was dropped, Seresin left the project and Parker became the only director connected to The Wall.[14]

Filming

.jpg)

Parker, Waters and Scarfe frequently clashed with each other during production, to the point where the director described the filming as "one of the most miserable experiences of my creative life."[15] Scarfe declared that he would drive to Pinewood Studios carrying a bottle of Jack Daniel's, because "I had to have a slug before I went in the morning, because I knew what was coming up, and I knew I had to fortify myself in some way."[16]

During production, while filming the destruction of a hotel room, Geldof suffered a cut to his hand as he pulled away the Venetian blinds. The footage remains in the film. Also, it was discovered while filming the pool scenes that Geldof did not know how to swim. Interiors were shot at Pinewood Studios, and it was suggested that they suspend Geldof in Christopher Reeve's clear cast used for the Superman flying sequences, but his frame was too small by comparison; it was then decided to make a smaller rig that was a more acceptable fit, and he simply lay on his back.[17]

The war scenes were shot on Saunton Sands in North Devon, which was also featured on the cover of Pink Floyd's A Momentary Lapse of Reason six years later.[18]

Release

The film was shown "out of competition" during the 1982 Cannes Film Festival.[19]

The film's official premiere was at the Empire, Leicester Square[21] in London, on 14 July 1982. It was attended by Waters and fellow Pink Floyd members David Gilmour and Nick Mason, but not Richard Wright,[21] who was no longer a member of the band. It was also attended by various celebrities including Geldof, Scarfe, Paula Yates, Pete Townshend, Sting, Roger Taylor, James Hunt, Lulu and Andy Summers.[22]

Box office and critical reception

The film opened with a limited release on 6 August 1982 and entered at No. 28 of the US box office charts despite only playing in one theatre on its first weekend, grossing over $68,000, a rare feat even by today's standards. The film then spent just over a month below the top 20 while still in the top 30. The film later expanded to over 600 theatres on 10 September, achieving No. 3 at the box office charts, below E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and An Officer and a Gentleman. The film eventually earned $22 million before closing in early 1983.[3]

The film received generally positive reviews. Reviewing The Wall on their television programme At the Movies in 1982, film critics Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel gave the film "two thumbs up". Ebert described The Wall as "a stunning vision of self-destruction" and "one of the most horrifying musicals of all time ... but the movie is effective. The music is strong and true, the images are like sledge hammers, and for once, the rock and roll hero isn't just a spoiled narcissist, but a real, suffering image of all the despair of this nuclear age. This is a real good movie." Siskel was more reserved in his judgement, stating that he felt that the film's imagery was too repetitive. However, he admitted that the "central image" of the fascist rally sequence "will stay with me for an awful long time." In February 2010, Roger Ebert added The Wall to his list of "Great Movies," describing the film as "without question the best of all serious fiction films devoted to rock. Seeing it now in more timid times, it looks more daring than it did in 1982, when I saw it at Cannes ... It's disquieting and depressing and very good."[23]

It was chosen for the opening night of Ebertfest 2010. Rotten Tomatoes currently ranks the film with a critics' review rating of 73% (based on 22 reviews). Danny Peary wrote that the "picture is unrelentingly downbeat and at times repulsive ... but I don't find it unwatchable – which is more than I could say if Ken Russell had directed this. The cinematography by Peter Biziou is extremely impressive and a few of the individual scenes have undeniable power."[24] Waters has expressed deep reservations about the film, saying that the filming had been "a very unnerving and unpleasant experience ... we all fell out in a big way." As for the film itself, he said: "I found it was so unremitting in its onslaught upon the senses, that it didn't give me, anyway, as an audience, a chance to get involved with it," although he had nothing but praise for Geldof's performance.[25] David Gilmour stated (on the "In the Studio with Redbeard" episodes of The Wall, A Momentary Lapse of Reason and On an Island) that the conflict between him and Waters started with the making of the film. Gilmour also stated on the documentary Behind The Wall (which was aired on the BBC in the UK and VH1 in the US) that "the movie was the less successful telling of The Wall story as opposed to the album and concert versions." Although the symbol of the crossed hammers used in the film was not related to any real racist group, it was adopted by white supremacist group the Hammerskins in the late 1980s.[26] It earned its creators two British Academy Awards; 'Best Sound' for James Guthrie, Eddy Joseph, Clive Winter, Graham Hartstone & Nicholas Le Messurier;[27] and 'Best Original Song' for Waters.[27]

Themes and analysis

It has been suggested that the protagonist stands in some way for Waters. Beyond the obvious parallel of them both being rock stars, Waters lost his father while he was an infant and had marital problems, divorcing several times.[28]

Romelo and Cabo place the Nazism and imperialism related symbols in the context of Margaret Thatcher's government and British foreign policy especially concerning the Falklands issue.[29]

Home media

Pink Floyd – The Wall was released on VHS in 1983 (MV400268), 1989 (M400268), 1994 (M204694) by MGM/UA Home Entertainment, and 1999 (CV50198) by Columbia Music Video.

The DVD was released in 1999 (UPC: 074645019895) and 2005 (UPC: 074645816395) by Columbia Music Video.

Awards

| List of awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

| BAFTA Film Award | Best Original Song | Roger Waters For the song "Another Brick in the Wall" | Won |

| BAFTA Film Award | Best Sound | James Guthrie Eddy Joseph Clive Winter Graham V. Hartstone Nicolas Le Messurier |

Won |

| Saturn Award | Best Poster Art | Gerald Scarfe | Nominated |

Documentary

A documentary was produced about the making of Pink Floyd – The Wall entitled The Other Side of the Wall that includes interviews with Parker, Scarfe, and clips of Waters, originally aired on MTV in 1982. A second documentary about the film was produced in 1999 entitled Retrospective that includes interviews with Waters, Parker, Scarfe, and other members of the film's production team. Both are featured on The Wall DVD as extras.

Soundtrack

| Pink Floyd - The Wall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Pink Floyd | ||||

| Released | Unreleased | |||

| Recorded | 1981–1982 | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Pink Floyd soundtracks chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Pink Floyd - The Wall | ||||

| ||||

The film soundtrack contains most songs from the album, albeit with several changes, as well as additional material (see table below).

The only songs from the album not used in the film are "Hey You" and "The Show Must Go On". "Hey You" was deleted as Waters and Parker felt the footage was too repetitive (eighty percent of the footage appears in montage sequences elsewhere)[15] but available to view as a bonus feature on the DVD release under the name "Reel 13".[30]

A soundtrack album from Columbia Records was listed in the film's end credits, but only a single containing "When the Tigers Broke Free" and the rerecorded "Bring the Boys Back Home" was released. "When the Tigers Broke Free" later became a bonus track on the 1983 album The Final Cut, an album Waters intended as an extension to The Wall. Guitarist David Gilmour, however, dismissed the album as a collection of songs that had been rejected for The Wall project, but were being recycled. The song, in the edit used for the single, also appears on the 2001 compilation album Echoes: The Best of Pink Floyd.

| Changes on the soundtrack album: | |

|---|---|

| Song | Changes |

| "When the Tigers Broke Free" 1 | New song, edited into two sections strictly for the film, but later released as one continuous song.[31] The song was released as a single in 1982 and was later included on the 2001 compilation Echoes: The Best of Pink Floyd and on the 2004 re-release of The Final Cut. |

| "In the Flesh?" | Extended/re-mixed/lead vocal re-recorded by Geldof.[31] |

| "The Thin Ice" | Extended/re-mixed[31] with additional piano overdub in second verse, baby sounds removed. |

| "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1" | Extra bass parts, which were muted on the album mix, can be heard. |

| "When the Tigers Broke Free" 2 | New song.[31] |

| "Goodbye Blue Sky" | Re-mixed.[31] |

| "The Happiest Days of Our Lives" | Re-mixed. Helicopter sounds dropped, teacher's lines re-recorded by Alex McAvoy.[31] |

| "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" | Re-mixed[31] with extra lead guitar, children's chorus part edited and shortened, teacher's lines re-recorded by McAvoy and interspersed within children's chorus portion. |

| "Mother" | Re-recorded completely with exception of guitar solo and its backing track. The lyric "Is it just a waste of time?" is replaced with "Mother, am I really dying?", which is what appeared on the original LP lyric sheet.[31] |

| "What Shall We Do Now?" | A full-length song which begins with the music of, and a similar lyric to "Empty Spaces". This was intended to be on the original album, and in fact appears on the original LP lyric sheet. At the last minute, it was dropped in favour of the shorter "Empty Spaces" (which was originally intended as a reprise of "What Shall We Do Now"). A live version is on the album Is There Anybody Out There? The Wall Live 1980–81.[31] |

| "Young Lust" | Screams added and phone call part removed. The phone call part was moved to the beginning of "What Shall We Do Now?" |

| "One of My Turns" | Re-mixed. Groupie's lines re-recorded by Jenny Wright. |

| "Don't Leave Me Now" | Shortened and remixed. |

| "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 3" | Re-recorded completely[31] with a slightly faster tempo. |

| "Goodbye Cruel World" | Unchanged. |

| "Is There Anybody Out There?" | Classical guitar re-recorded, this time played with a leather pick by guitarist Tim Renwick[32], as opposed to the album version, which was played finger-style by Joe DiBlasi. |

| "Nobody Home" | Musically unchanged, but with different clips from the TV set. |

| "Vera" | Unchanged. |

| "Bring the Boys Back Home" | Re-recorded completely with brass band and Welsh male vocal choir extended and without Waters' lead vocals.[21] |

| "Comfortably Numb" | Re-mixed with Geldof's scream added. Bass line partially different from album. |

| "In the Flesh" | Re-recorded completely with brass band and Geldof on lead vocals.[31] |

| "Run Like Hell" | Re-mixed and shortened. |

| "Waiting for the Worms" | Shortened but with extended coda. |

| "5:11 AM (The Moment of Clarity)" | Geldof unaccompanied on lead vocals. The song is taken from The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, a concept album Waters wrote simultaneously with The Wall, and later recorded solo. Geldof sings the lyrics to the melody of "Your Possible Pasts", a song intended for The Wall that later appeared on The Final Cut. |

| "Stop" | Re-recorded completely[31] with Geldof unaccompanied on lead vocals. (The audio in the background of this scene is from Gary Yudman's introduction from The Wall Live at Earl's Court.) |

| "The Trial" | Re-mixed. |

| "Outside the Wall" | Re-recorded completely[31] with brass band and Welsh male voice choir. Extended with a musical passage similar to "Southampton Dock" from The Final Cut.[33][34] |

- Chart positions

| Year | Chart | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Australian ARIA DVD Chart | #10 |

References

- ↑ "PINK FLOYD - THE WALL (AA)". British Board of Film Classification. 23 June 1982. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ BRITISH PRODUCTION 1981 Moses, Antoinette. Sight and Sound; London Vol. 51, Iss. 4, (Fall 1982): 258.

- 1 2 Box Office Information for Pink Floyd – The Wall. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ↑ Curtis, James M. (1987). Rock Eras: Interpretations of Music and Society, 1954–1984. Popular Press. p. 283. ISBN 0-87972-369-6.

- ↑ Reisch, George A. (2007). Pink Floyd and Philosophy: Careful With That Axiom, Eugene!. Open Court Publishing Company. pp. 76–77. ISBN 0-8126-9636-0. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Reisch, George A. (2009). Radiohead and philosophy. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 60. ISBN 0-8126-9700-6. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Schaffner, Nicholas. Saucerful of Secrets. Dell Publishing. p. 225.

- 1 2 3 J.C. Maçek III (5 September 2012). "The Cinematic Experience of Roger Waters' 'The Wall Live'". PopMatters.

- ↑ Schaffner, Nicholas. Saucerful of Secrets. Dell Publishing. p. 244.

- ↑ Schaffner, Nicholas. Saucerful of Secrets. Dell Publishing. pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Schaffner, Nicholas. Saucerful of Secrets. Dell Publishing. pp. 245–246.

- ↑ Schaffner, Nicholas. Saucerful of Secrets. Dell Publishing. p. 246.

- ↑ Pink Floyd's The Wall, page 83

- ↑ Pink Floyd's The Wall, page 105

- 1 2 Pink Floyd's The Wall, page 118

- ↑ "Interview: Gerald Scarfe". Floydian Slip. November 5–7, 2010. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Geldof, Bob. Is That It?. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ↑ Storm Thorgerson and Peter Curzon. Mind Over Matter: The Images of Pink Floyd. page 102. ISBN 1-86074-206-8.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes – From 16 to 27 may 2012". Festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ Scarfe, Gerald. The Making of Pink Floyd: The Wall. Da Capo Press. p. 216.

- 1 2 3 Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd – The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus,. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ↑ Miles, Barry; Andy Mabbett (1994). Pink Floyd the visual documentary ([Updated ed.] ed.). London :: Omnibus,. ISBN 0-7119-4109-2.

- 1 2 "Pink Floyd: The Wall (1982)". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic (Simon & Schuster, 1986) p.331

- ↑ Pink Floyd's The Wall, page 129

- ↑ "The Hammerskin Nation". Extremism in America. Anti-Defamation League. 2005. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- 1 2 "Past Winners and Nominees – Film – Awards". BAFTA. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ "Roger Waters: Another crack in the wall | The Sunday Times". www.thesundaytimes.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- ↑ "Roger Waters' Poetry of the Absent Father: British Identity in Pink Floyd's "The Wall" on JSTOR". JSTOR 41055246. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ Pink Floyd's The Wall, page 128

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Bench, Jeff (2004). Pink Floyd's The Wall. Richmond, Surrey, UK: Reynolds and Hearn,. pp. 107–110p. ISBN 1-903111-82-X.

- ↑ Marty Yawnick (June 28, 2016). "Is There Anybody Out There? - Hear David Gilmour's version". The Wall Complete. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ↑ Pink Floyd: The Wall (1980 Pink Floyd Music Publishers Ltd., London, England, ISBN 0-7119-1031-6 [USA ISBN 0-8256-1076-1])

- ↑ Pink Floyd: The Final Cut (1983 Pink Floyd Music Publishers Ltd., London, England.)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pink Floyd – The Wall |