Peter Manigault

.jpg)

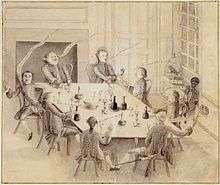

Peter Manigault (October 10, 1731 – November 12, 1773) was a Charleston, South Carolina attorney, plantation owner, and colonial legislator. He was the wealthiest man in the British North American colonies at the time of his death.

Early life

Manigault (pronounced MAN-eh-go) was born in Charleston on October 10, 1731, and was part of a wealthy French Huguenot immigrant family.[1] Manigault was the son of Gabriel Manigault (1704-1781) and Ann Ashby Manigault (1705-1782).[2] Manigault was a descendant of Pierre Manigault, a French Huguenot who settled in the Santee area and became a successful rice planter.[3]

He was privately educated in the Province of South Carolina and in England, traveled extensively in Europe, studied law at London's Inner Temple, and was called to the British bar in 1752.[4]

Career

He returned to South Carolina in 1754, where he practiced law, became a successful merchant and banker, and managed his family's slaves and extensive plantation holdings. By 1774 Manigault was the wealthiest person in the British North American colonies, with his net worth of approximately £33,000 in 1770 equal to approximately $4 million in 2016.[5]

Manigault served in the South Carolina House of Commons in 1755, and again from 1766 to 1773.[6] From 1765 to 1772 he was Speaker of the House.[7] He actively opposed the British Stamp Act 1765, and was identified with what became known as the Patriot cause.[8]

Letters

During Manigault's studies in London and travels in Europe, he exchanged frequent letters with his parents. This correspondence was published as part of several articles over several years in the South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine.[9]

Personal life

.jpg)

He was the husband of Elizabeth Wragg Manigault (1736–1773).[10] She was the daughter of Joseph (d. 1751) and Judith Wragg (d. 1769). Their children included:[11]

- Gabriel Manigault (1758–1809), who married Margaret Izard (1768–1824)[11]

- Anne Manigault Middleton (1762–1811), who married Thomas Middleton (1753–1797)[11]

- Joseph Manigault (1763–1843), who married Charlotte Drayton (1781–1855)[11]

- Henrietta Manigault Heyward (1769–1827), who married Nathaniel Heyward (1766–1851).[11]

In 1773, Manigault's health worsened, and he left South Carolina for England in an effort to find a cure.[12] His wife died on February 19, 1773. Manigault's health did not improve, and he died in London on November 12, 1773.[13] He was buried at French Protestant Huguenot Church Cemetery in Charleston.[14][15]

Descendants

Through his son, he was the grandfather of Elizabeth Manigault Morris (1785–1822), who married Lewis Morris (1785–1863), a grandson of Lewis Morris,[16] Gabriel Henry Manigault (1788–1834), and Charles Izard Manigault (1795–1874).[17][18]

See also

References

- ↑ Garraty, John Arthur (1999). American National Biography. 14. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 411.

- ↑ Gardner, Albert Ten Eyck; Feld, Stuart P. (1965). American Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. I. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society. p. 17.

- ↑ Ingham, John N. (1983). Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders. 2. Greenwood Press: Greenwood Press. p. 851. ISBN 978-0-313-23908-3.

- ↑ Salley, A. S., Jr. (1902). The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine. 3. Charleston, SC: South Carolina Historical Society. p. 87.

- ↑ Walter B. Edgar (1998). South Carolina: A History. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 153.

- ↑ Board of Managers, Society of Colonial Dames of the State of New York (1913). Register of the Colonial Dames of the State of New York, 1893-1913. New York, NY: Frederick H. Hitchcock. p. 348.

- ↑ Woodmason, Charles (1953). The Carolina Backcountry on the Eve of the Revolution. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-8078-4035-1.

- ↑ Ramsay, David (1809). The History of South-Carolina. 2. Charleston, SC: David Longworth. pp. 504–505.

- ↑ Haw, James (1997). John & Edward Rutledge of South Carolina. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-8203-1859-2.

- ↑ Hain, Pamela Chase (2005). A Confederate Chronicle: The Life of a Civil War Survivor. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8262-1599-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The North Carolina Historical Review. 47. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Historical Commission. 1970. p. 17.

- ↑ Webber, Mabel Louise, South Carolina Historical Society (July 1, 1914). "Six Letters of Peter Manigault". The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine. Charleston, SC: Walker, Evans & Cogswell. XV (3): 113.

- ↑ McDonough, Daniel J. (2000). Christopher Gadsden and Henry Laurens: The Parallel Lives of Two American Patriots. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-57591-039-0.

- ↑ Laurens, Henry (1981). The Papers of Henry Laurens. 9. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-87249-399-5.

- ↑ Peter Manigault at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Manigault, Morris, and Grimball Family Papers, 1795-1832". finding-aids.lib.unc.edu. Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Charles Izard Manigault and His Family in Rome - Ferdinando Cavalleri - Google Arts & Culture". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Charles Izard Manigault | Gibbes People's Choice". www.gibbespeopleschoice.org. Retrieved 14 December 2017.