Persepolis (comics)

| Persepolis | |

|---|---|

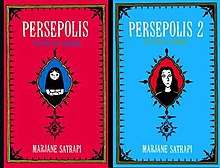

Covers of the English version of Persepolis Books 1 and 2 | |

| Date | 2000 |

| Publisher | L'Association |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Marjane Satrapi |

| Original publication | |

| Date of publication | 2000 |

| ISBN | 2844140580 |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Pantheon Books |

| Date | 2003, 2004, 2005 |

| ISBN | 0-224-08039-3 |

Persepolis is a graphic autobiography by Marjane Satrapi that depicts her childhood up to her early adult years in Iran during and after the Islamic Revolution. The title is a reference to the ancient capital of the Persian Empire, Persepolis. Newsweek ranked the book #5 on its list of the ten best non-fiction books of the decade.[1] Originally published in French, the graphic novel has been translated from French to English, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, Italian, Greek, Swedish, Georgian, and other languages, and has sold 1,500,000 copies overall.

French comics publisher L'Association published the original work in four volumes between 2000 and 2003. Pantheon Books (North America) and Jonathan Cape (United Kingdom) published the English translations in two volumes – one in 2003 and the other in 2004. Omnibus editions in French and English followed in 2007, coinciding with the theatrical release of the film adaptation.

Satrapi and comic artist Vincent Paronnaud co-directed the animated movie, also titled Persepolis. Although the film emulates Satrapi's visual style of high-contrast inking, a present-day frame story is rendered in color. In the United States, Persepolis was nominated for Best Animated Feature at the 2007 Academy Awards.

Background

Persepolis depicts Satrapi's childhood in Iran during the Islamic Revolution, while Persepolis 2 depicts her high school years in Vienna, Austria, including her subsequent return to Iran where she attends college, marries, and later divorces before moving to France. Hence, the series is not only a memoir, but a Bildungsroman. The novel narrates “counter-historical narratives that are mostly unknown by a Western reading public.[2]” Persepolis is a reminder of the “precarity of survival” in political and social situations such as those faced by Satrapi as a child in Iran.[2]

Persepolis has won numerous awards, including one for its text at the Angoulême International Comics Festival Prize for Scenario in Angoulême, France, and another for its criticism of authoritarianism in Vitoria, Spain. The film version has also received high honors, specifically, in 2007, it was named the Official French Selection for the Best Foreign Language Film.[3] Marie Ostby points out that “Satrapi’s work marks a watershed movement in the global history of the graphic novel,[4]” exemplified by the recent increase in use of the graphic novel as a “cross-cultural form of representation for the twenty-first century Middle East.[4]”

Sectional summary

Persepolis 1: The Story of a Childhood

— Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis 1: The Story of the Childhood (p. 143)

The graphic novel begins with an introduction to the life of a ten year old - Marji - in 1980, the year after the Islamic Revolution. Satrapi focuses on a child’s view of the Islamic Revolution, a time when girls were obliged to wear the veil, schools were segregated by gender (whereas Marji previously attended a co-ed school), and secular education was abolished. In school, Marji learns about revolutions and socialism while observing oppression by the Shah in her daily life. Although her anti-authoritarian/patriarchy attitude is inspired by her favorite comic book “Dialectic Materialism,” but is too young to attend protests.

Marji uncovers her family background. In 1925, Reza Shah, the father of the current king, was influenced and supported by the British to organize a coup d’état to overthrow the Qajar emperor, who happens to be Marji's great-grandfather. The Shah confiscated everything belonging to her grandfather’s family and her Western-educated grandfather was appointed as prime minister, but was imprisoned after his turn to communism. Marji vows to read everything she can to better understand the Revolution.

Through her research, Marji reads a work by Ali Ashraf Darvishian - a Kurdish author - illuminating the class structures in her society. This prompts Marji to reflect on her own home, specifically with her nursemaid Mehri and of Mehri’s failed past love, which father explains "impossible” since one must stay in one’s own social class. Marji sees this as unjust and convinces Mehri to attend anti-Shah demonstrations with her on Black Friday. They are unhurt, but the Black Friday massacre was the beginning of an extended period of violence, leading to the decline and exile of the Shah in Egypt. The celebration of his exile prompts Marji to become more aware of politics and human fickleness, as she observes former supporters of the Shah now touting pro-revolution propaganda.

On March 1979, 3,000 political prisoners were released. The end of the Revolution brought about an end to her interest in “Dialectical Materialism” comics and Marji seeks solace in her faith. Her uncle Anoosh visits Marji and recounts how he was imprisoned for nine years as a communist revolutionary and hero. As he re-tells his story, he states that Marji’s grandfather was loyal to the Shah, but him and his uncle Fereydoon were devoted to ideals of justice and democracy. They attempted to bring about independence from the shah; however, he was later imprisoned. He encourages Marji to remember his story, even if she has difficulty understanding it, because it is their “family memory” and it must not be lost. Marji’s family soon discovers that their communist-revolutionary friends who had just been released from prison are either dead or fled, and Anoosh is arrested and executed as a Russian spy. These events leave Marji feeling lost and she rejects her faith. Bombs begin to fall on Iran. As fundamentalist students were reported taking over the U.S. embassy, Marji’s family observes their neighbors once again changing their behavior to suit the new regime. Her family goes on an abrupt vacation for three weeks to Spain and Italy, only to return home to the announcement of war with Iraq - the second Arab invasion in 1400 years. Marji’s father is doubtful of Iran’s ability to defend itself since all pilots of the fighter jets were either jailed or executed after a failed coup d’état and is disillusioned with the Islamic-Fundamentalist government, an attitude that Marji interprets as defeatist and unpatriotic.

Although the Iraqi army had more modern weaponry, Iran had a greater number of young soldiers. Marji notices the number of ‘martyrs’ reported in the daily news and the twice-daily funeral marches with self-flagellation sessions at her school. After the border towns, Tehran itself became a target, and the basement of Marji’s building was turned into a bomb shelter. Having weekly parties or card games with wine expertly and secretly made by Marji’s uncle was their only way to alleviate the stress of their new lives and a way to privately revolt against the new regime.

After two years of war, at age twelve (1982), Marji is very astute and begins to explore her rebellious side by skipping classes and obsessing over boys. Iranian army has successfully pushed the Iraqi army back to the borders; however the war did not end. The fundamentalist regime uses war as an excuse to exterminate all internal enemies and became more oppressive.

Marji’s parents go on a holiday to Turkey once the borders are reopened in 1983 and smuggle banned gifts back to Iran for her. Marji ventures out to connect with the black market that has grown around the shortages caused by war and repression. She is stopped by members of the new woman’s branch of the Guardians of the Revolution who are unimpressed with her new ‘symbols of decadence’ - improperly worn head scarf and too-tight jeans - and threaten to bring her in front of their HQ committee where she would likely be physically punished or detained without consent.

One fatal Saturday, Marji rushes home when she discovers a long-range ballistic missile has hit her street. After succumbing to her own sadness and trauma after the personal discovery of her friend’s body, Marji is suddenly overcome with rage. At age fourteen, Marji becomes a fearless rebel and is expelled from school after punching the principal. Her mother is gripped with fear by her rebelliousness, explaining that she risks execution. To circumvent the law against killing a virgin, a Guardian of the Revolution will marry a condemned young woman, forcibly take her virginity, execute her, then send a meagre dowry and message to her family. Her family decides to send her to Austria to attend French school. Her parents send her off at the airport, and when Marji looks behind her before boarding the plane she sees her mother has fainted.

Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return

The Soup

When Marji arrives in Vienna, she leaves Zozo’s home and starts her new life at a boarding house run by nuns. There, she goes shopping by herself for the first time and enjoys her newfound freedom. When she returns, she meets her roommate, Lucia. Lucia speaks German, but they quickly learn to communicate by drawing pictures. The section ends with both girls watching a movie in the TV room.

Tyrol

Marji starts to become popular at school after she gets the highest grade on a math test and her unflattering portraits of teachers spark new friendships. She and her new friends talk about what they will do over Christmas break, which makes Marji feel left out because she doesn't celebrate Christmas, but rather the Iranian New Year, which isn't until March. After expressing her sadness to Lucia, Lucia offers to take her home to meet her parents over the holiday. Marji agrees and ends up going to evening mass and having dinner with them.

Pasta

The next break, Marji listens to her friends' plans and comes up with her own excuse for what she is going to do: read. She spends her break reading and eating pasta. One evening she makes a big potful of spaghetti and goes down to eat it in the public TV room at her boarding house. One of the nuns tells her off, and then insults her for being an uneducated Iranian. Marji bites back, which gets her kicked out of the boarding house. She says goodbye to Lucia and leaves to stay with her friend Julie and her mother.

The Pill

Marji starts living with Julie and is disturbed by how disrespectful she is to her mother, whom Marji respects. Marji and Julie have a talk before bed, and Julie tells Marji about her sexual endeavors. Marji is shocked because sexual topics were very taboo in Iran. Julie's mother goes on a business trip and Julie has a party, but it is not what Marji expects. Instead of eating and dancing, people are lying around and smoking. Later that night, Marji is appalled upon hearing that Julie and her boyfriend are having sex. Marji would later call this her first step towards assimilating into Western culture.

The Vegetable

Marji discusses her changing physical appearance. She starts cutting her own hair, and even selling haircuts to the hall monitors at her school. Marji’s friends, who think the hall monitors are conformists, are displeased. Her friends begin to use drugs and she only pretends to participate. She begins to feel like she is betraying her Iranian heritage. Finally, she overhears some people in a café talking about how she has made up her past, and defends herself, which makes her feel as if she has redeemed herself.

The Horse

Julie leaves Vienna and Marji moves to a communal apartment with eight homosexual men. Her mother surprises her by calling to say she is coming to visit, and arrives soon after. Marji spends time with her mother and, because the apartment is only hers for a limited amount of time, finds a new place to stay – a room in the house of Frau Dr. Heller.

Hide and Seek

Marji starts having problems with Frau Dr. Heller’s unstable attitude and untidy dog. Marji 's boyfriend Enrique invites her to a party, and, although it is not what she expects, she has fun. She meets Enrique's friend Ingrid, and when she wakes up in the morning without Enrique beside her, jumps to the conclusion that he is in love with Ingrid. However, later that day, Enrique reveals to Marji that he is gay. Marji is confused, and has a long talk with her physics teacher. She decides that she wants a physical relationship, and, after failing miserably with the boy she likes, turns to drugs. She soon meets Markus, a student at her school, and falls in love with him, but neither Markus's mother nor Frau Dr. Heller approves of their relationship. Marji procures some drugs for Markus, and gains a reputation as a drug dealer; Marji feels ashamed.

The Croissant

Marji is having trouble on her exams, so she calls and asks her mother to pray for her. In need of money, she ends up getting a job at a cafe and befriends the elderly cook. When the school year starts, the principal subtly chastises her for drug dealing. She stops, but ends up taking more of them herself – so many that her boyfriend Markus gets fed up and it begins affecting her health. She gets involved with some of Markus' friends and protests the new Austrian president, Kurt Waldheim, a former Nazi. Marji prepares to go away to spend her birthday with a friend and is distressed by Markus's nonchalant reaction. When she ends up missing her train, she goes to Markus's house, only to discover that he is cheating on her.

The Veil

Marji falls apart after her breakup with Markus. When she is accused of stealing Frau Dr. Heller's brooch, she decides to leave, spending the day on a park bench, where she reflects upon how cruel Markus was to her. She discovers that she has nowhere to go and ends up having to live on the street for over two months. During this time, she contracts severe bronchitis and ends up in the hospital. When she recovers, she remembers her mother telling her that a friend in Vienna owes her some money. She goes to pick it up, and discovers that her parents have been desperately trying to contact her for the two months she spent on the streets. She arranges with her parents to go back to Iran.

The Return

After living in Vienna for 4 years, Marji finally returns to Tehran. She can feel the oppression in the air, now more so than ever. At the airport, she recognizes her parents instantly, observing that the war has aged them. Marji has changed so much, her parents don't even recognize her until she approaches them herself. The next morning, she takes notice of the things around her room that were remnants of her younger "punk" years. She sponges off a punk she had drawn on her wall as a symbolic move into the future. Donning her veil once more to go out, she takes in the 65-foot murals of martyrs, rebel slogans, and the streets renamed after the dead. At home, her father tells Marji the horrors of the war and they talk deep into the night. After hearing what her parents had gone through while she was away in Vienna, she resolves never to tell them of her time there.

The Joke

Despite her opposition, Marji’s entire family and later, her friends, come to visit. Marji feels awkward because all her friends "looked like American TV heroines.” A few days later, she tells her Mom the only friend she would like to see is Kia, whom she discovers was required to do military service and is now disabled. Marji relieved that he still sounds normal of the phone, but is taken aback when she sees him in a wheelchair. At his home, Kia tells Marji the story of an injured veteran with an unfortunate ending, yet Kia makes a joke and they share a long laugh about it.

Skiing

Marji falls into a depression. Her friends suggest a ski trip, which Marji reluctantly invitation. She is criticized for admitting that she has had multiple sexual experiences and returns home even more depressed. She decides to visit a therapist, but is still unsatisfied, visiting two more until the last one simply puts her on medication. When her parents leave for a vacation, she drinks half a bottle of vodka and tries to slit her wrists. When that fails, she decides to swallow all her anti-depressant pills, but wakes up three days later, taking this as a sign that she shouldn't die. She begins a self-transformation that includes hair-removal, a new wardrobe, a perm, makeup, and exercise, which leads to her new job as an aerobics instructor.

The Exam

Marji goes to a party hosted by a new friend of hers named Roxana. There she meets a young man named Reza, who she is warned is a "lady's man." and someone to watch out for. After a while, Marji realizes that the rumors about Reza are false and ill-intentioned. Marji and Reza hit it off and become a couple. They decide to move out of the country to have a better future for themselves. They both study hard for the National Exam in order to enter University, so as not to feel like they have wasted their lives, and pass. Marji is admitted for Graphic Arts and when she goes home to tell her parents, they tell her that she has a few more things to learn. Marji prays for the strength.

The Makeup

When on the street, Marji sees a bus and car full of guards, which she knows indicates a raid. Marji is wearing lipstick, which is illegal in Iran. To evade capture, she informs the guards that an innocent man spoke indecently to her. The guards arrest the man. Later, she meets up with Reza and they are confronted by guards because it is not socially acceptable for her to be with a man to whom she isn’t married. They are forced to pay a fine to evade torture. Afterwards, Marji tells the story of the innocent man to her grandma and is scolded for her selfishness.

The Convocation

Because they are not married, Marji and Reza have to hide their love from the general public. At the University the students are still divided by sex, but that doesn't stop any of them from flirting with one another. Marji makes friends with two other women from the University; Niyoosha and Shouka. There is a meeting in the amphitheater with the administrators of the University to lecture the students on how they need to dress more modestly. Marji speaks out against their hypocrisy for not showing the same treatment toward men. She claims that as an art student she needs to work more freely without the constraints of her headscarf. Marji is then summoned by the Islamic Commission, where she receives a warning. Her grandmother tells her that she is very proud of her for sticking up for herself and other citizens.

The Socks

Marji continues to take art classes, but they are becoming quite difficult for various reasons. Marji, Reza and their friends try to live a normal life as possible. They hold secret parties at each other's houses until one day, a group of Guardians of the Revolution catch them through the apartment window, arresting the women and some of the men. Farzad, who tries to escape by roof-jumping, falls to his death. Those arrested get bailed out of jail by their parents and meet up to grieve over the loss of their friend.

The Wedding

In 1991 Reza proposes marriage to Marji, and after some contemplation, she accepts. Shortly after, with their parents’ blessings (Marji's mother takes some convincing), they have a big wedding. During the wedding celebration, Marji senses her mother is unhappy, and talks to her in the restroom. Taji admits she is disappointed that Marji wants to get married so young. Marji reassures her that this is what she wants, but as soon as the wedding ends, she realizes she feels trapped in the role of a permanent wife. Married life for Marji and Reza spirals out of control.

The Satellite

The war between Iraq and Kuwait has begun and panic is starting to spread throughout Europe. Many Iranians, however, are simply happy to no longer be at war. Later on a friend of Marji's named Fariborz invites them over to see the new satellite antenna he has had installed. They spend hours at his house watching anything they could without the Islamic regime's control. Meanwhile, Ebi senses that Marji is not happy in her marriage and tries to talk to her about it, but Marji storms off. She prefers to spend her time these days conversing with older intellectuals about politics.

The End

In 1994 Marji and Reza decide to put aside their differences and work together on a project for their end of the year University assignment before graduation. They are assigned to create a theme park based on their mythological heroes. They have to present their project to a panel of judges for their dissertation. They receive a twenty out of twenty mark and are praised for their hard work. The main judge mentions that they should propose their project to the mayor of Tehran. Marji goes to the mayor with the work and shows him one of her drawings of Gord Afarid. The mayor is impressed with the work but comments that it would ultimately be unacceptable, as many of the female characters are without veils. Marji leaves disappointed.

Later on, Marji confides in Farnaz that she no longer loves Reza and wants a divorce. But Farnaz tells her that divorced women would be forever scorned so she would be better off staying. Marji confides in her grandmother, and her grandmother tells her that if she wants a divorce then she has every right to have one, admitting that she had been divorced herself. After much contemplation, including a few incidents at her new job as an illustrator for an economics magazine, Marji decides it's time to talk with Reza about separating. He tells her that he still wants to try to make it work and that he is still in love with her, but Marji insists that this is for the best, and that if they stay together any longer, the love will eventually dissipate and then they will truly feel trapped. Marji goes to her parents and tells them about her and Reza's divorce. Her father admits that he knew it would happen eventually, but never said anything because he wanted Marji to learn from her own mistakes. Her parents tell her that despite everything, they are still very proud of her and admire her growing maturity over the years. Her parents suggest that she should leave Iran permanently and live a better life back in Europe.

In late 1994 before her departure for Europe, Marji takes a trip to the countryside outside of Tehran to get one last taste of the Iranian scenery. She also goes to the Caspian Sea with her grandmother, visits the grave of her grandfather, and goes behind the prison building where her uncle Anoosh is buried. She spends the rest of the summer with her parents. In the autumn, Marji along with her parents and grandmother go to Mehrabad Airport for their final goodbye as she heads off to live in Paris. After many tears, Marji's mother tells her, "This time, you're leaving for good. You are a free woman. The Iran of today is not for you. I forbid you to come back!" Marji agrees. Marji gets behind the gate ready to board the plane and turns around one final time to wave goodbye to her family. The last time Marji sees her grandmother is during the Iranian New Year of 1995, as she dies in 1996. The book ends with the final quote, "Freedom had a price."

Publication history

The original French series was published by L'Association in four volumes, one volume per year, from 2000 to 2003. David B., Satrapi’s publisher, worked to “create a forum for more culturally informed, self-reflective work.[4]” L’Association published Persepolis as one of their three “breakthrough political graphic memoirs.[4]”Persepolis, tome 1 ends at the outbreak of war; Persepolis, tome 2 ends with Marji boarding a plane for Austria; Persepolis, tome 3 ends with Marji putting on a veil to return to Iran; Persepolis, tome 4 concludes the work. When the series gained critical acclaim, it was translated into many different languages. In 2003, Pantheon Books published parts 1 and 2 in a single volume English translation (with new cover art) under the title Persepolis which was translated by Blake Ferris and Mattias Ripa, Satrapi's husband; parts 3 and 4 (also with new cover art) followed in 2004 as Persepolis 2, translated by Anjali Singh. In October 2007, Pantheon repackaged the two English language volumes in a single volume (with film tie-in cover art) under the title The Complete Persepolis. The cover images in the publications from both countries feature Satrapi’s own artwork; however, the French publication is much less ornamented than the United States equivalent.[4]

Genre/Style

Persepolis is a non-fictional graphic autobiography, or a graphic novel based on Satrapi's life. The genre of graphic novels can be traced back to 1986 with Art Spiegelman’s depiction of the Holocaust through the use of cartoon images of mice and cats. Later, writers such as Aaron McGruder and Ho Che Anderson used graphic novels to discuss themes such as Sudanese orphans and civil rights movements. According to Hamid Naficy, this genre has “become an acceptable medium for discussing serious matters,[5]” by using illustrations to discuss foreign topics, such as those discussed in Persepolis.[5] The “graphic novel” label is not so much a single mindset as a coalition of interests that happen to agree on one thing—that comics deserve more respect.[6] It is part of a "new wave of autobiographical writing by diasporic Iranian women."[7] Satrapi wrote Persepolis in a black-and-white format: "the dialogue, which has the rhythms of workaday family conversations and the bright curiosity of a child's questions, is often darkened by the heavy black-and-white drawings".[8] The use of a graphic novel has become much more predominant in the wake of events such as the Arab Spring and the Green Movement, as this genre employs both literature and imagery to discuss these historical movements.[4] In an interview titled "Why I Wrote Persepolis",[9] Marjane Satrapi said that "graphic novels are not traditional literature, but that does not mean they are second-rate."[10]

An article[11] written about teaching Persepolis in a middle school classroom acknowledges Satrapi's decision to use this genre of literature as a way for "students to disrupt the one-dimensional image of Iran and Iranian women. In this way, the story encourages students to skirt the wall of intolerance and participate in a more complex conversation about Iranian history, U.S. politics, and the gendered interstices of war."[11] The Modern Language Association of America published an article in 2017 that discusses how Satrapi “works through a perpetually dual vocabulary of image and text,” representing Iranian and European culture through drawings and language.[4]

Persepolis uses visual literacy through its comics to enhance the message of the text. As defined by the Encyclopedia of the Social and Cultural Foundations of Education, "Visual literacy traces its roots to linguistic literacy, based on the idea that educating people to understand the codes and contexts of language leads to an ability to read and comprehend written and spoken verbal communication."[12]

"Visual literacy is based on the idea that pictures can be "read"".[13] For example, on page 77, Satrapi writes: “Things got worse from one day to the next. In September 1980, my parents abruptly planned a vacation. I think they realized that soon such things would no longer be possible.”[14] The accompanying image includes a female figure rising within gusts of wind and above are Marjane and her parents flying on a carpet—an example of the imagery of this novel adding and enhancing the message of Satrapi's text.

Character list

- Marjane (main character): nicknamed Marji- a strong girl who follows her parents' footsteps. Marjane's view of the world changes as she matures, but remains a rebellious fighter—actions which sometimes get her into trouble.

- Mrs. Satrapi or Taji (Marjane's mother): Taji is a passionate woman, who is upset with the way things are going in Iran, including the elimination of personal freedoms, and violent attacks on innocent people. She actively takes part in her local government by attending many protests.

- Mr. Satrapi, Ebi, or Eby (Marjane's father): He also takes part in many political protests with Taji. He takes photographs of riots, which was illegal and very dangerous, if caught.

- Marjane's Grandmother: Marjane's Grandmother develops a close relationship with Marjane. She enjoys telling Marjane stories of her past, and Marjane's Grandfather.

- Uncle Anoosh is Marjane's father's brother. At 18, he joined his paternal uncle Fereydoon (Marjane's paternal grandfather's brother) who had linkage to Iranian Azerbaijan, proclaiming independence from Shah's Iran. In response to the Shah's regime, Anoosh fled Iran to the Soviet Union, went to Leningrad then settled in Moscow. He obtained a PhD in Marxism–Leninism, married a Russian woman, and had two daughters before getting divorced. In 1970 he returned to Iran in disguise where he got arrested and spent nine years in prison. He was let out due to the shah’s overthrow and Marjane met him for the first time- she saw him as a hero, they develop a close relationship and is eventually executed by the new Islamic revolutionary authorities.

- Zozo: Marjane's mother's friend from Iran who left the country following the Islamic Revolution with her husband Houshang and their daughter Shirin to live in Vienna. In 1984, as part of the decision to send their 14-year-old daughter Marjane outside of the country to Vienna, Ebi and Taji arranged for her to be picked up by Zozo at the airport as well as to stay with Zozo's family at their apartment. The stay proved short, however, as Zozo, unhappy with her own family's living situation in Vienna, quickly made it clear to Marjane that she would not be able to continue living with them. Instead, after conferring with Taji back in Iran over the phone, Zozo arranged for Marjane to move to a Catholic boarding facility in Vienna.

- Lucia: Marjane's roommate at the Catholic boarding facility in Vienna.

- Julie: A teenage friend and schoolmate of Marjane's who takes her in when she is kicked out of the Catholic boarding facility in Vienna. Raised by a single mother, Julie is four years older than Marjane and the two become close friends despite the age difference. Julie is already sexually active with different men and very open, blunt, and direct about sex, unlike teenage Marjane who is sexually timid and still a virgin.

- Kia: One of Marjane's childhood friends who eventually left for America.

- Siamak and Mohsen: Marjane's parents' family friends who were imprisoned by Shah Reza Pahlavi's regime for their activity in Marxist and communist political organizations within Iran. Mohsen got jailed in April 1971 while Siamak met the same fate in July 1973. During her husband's incarceration, Siamak's wife regularly socializes with Ebi and Taji, while her and Siamak's little daughter Laly plays with Marji. Both Siamak and Mohsen were beaten and tortured in prison. In March 1979, following the Shah's overthrow, both got released. However, once the Islamic fundamentalist regime took power in Iran following the revolution, Mohsen is found drowned in his bathtub (believed to be murder, seeing as only his head is underwater) while Siamak, his wife, and their daughter managed to escape Iran, crossing the border hidden among a flock of sheep.

- Mehridia: Mahrida, Mariane's house's maid, became friends with Marjane during her childhood. She had a secret relationship with the neighbor boy. She was illiterate, so she had Marjane write love letters to the neighbor boy for her.

- Mali: Marjane's mother's childhood friend whose family house in Abadan got destroyed during the Iraqi forces' bombing of the city. Along with her husband and their two adolescent sons, she fled Abadan and arrived to Teheran where they stayed with the Satrapis for a week.

- Uncle Taher: Marjane's uncle through marriage, having married her maternal aunt. Emotionally worn out after parting with his adolescent son whom he and his wife sent to Holland immediately following the Islamic Revolution, Taher's fragile health has been in rapid decline ever since. His worsening heart condition culminated in July 1982, amidst Iraqi bombing raids of Tehran and internal door-to-door persecution by Iran's Islamic authorities of individuals suspected of counter-revolutionary activity, with a massive heart attack requiring open heart surgery that couldn't be performed in the country. Needing a passport for her severely ill husband to travel abroad for surgery, Taher's wife, Marjane's aunt, tried official legal channels in order to obtain the travel documents, but quickly realized the process would be slow, difficult, and uncertain. To that end, Marjane's father Ebi decided to pay a visit to Khosro, an old acquaintance who recently began making forged documents, in order to see if getting a fake passport would be possible.

- Khosro: Communist sympathizer whose activist brother was imprisoned together with Anoosh during the reign of the Shah. While his brother was jailed, Khosro owned a publishing company, however, after the Islamic authorities shut it down following the Islamic Revolution, he took to creating fake passports for people who wanted to leave Iran during the 1980-1983 closed borders period in the early years of the Iran-Iraq War when obtaining travel documents legally was extremely difficult. He even created one for his own brother who having been released from Shah's prison got harassed regularly by the new Islamic authorities for his counter-revolutionary activity; with the fake passport, Khosro's brother was able to safely flee to Sweden. Prior to that, Khosro's wife and their daughter Mandana left Iran right after the Revolution. Khosro also harboured communists on the run from the Islamic regime such as eighteen-year-old Niloufar whose brother used to be his messenger boy. Khosro had to flee to Sweden when the Guardians ransacked his company and arrested Niloufar, who was executed shortly afterwards.

- Reza: Marjane's husband of 2 years

Reception

Upon its release, the graphic novel received high praise, but was also met with criticism and calls for censorship.TIME included Persepolis in its "Best Comics of 2003" list.[15] Andrew Arnold of TIME described Persepolis as, "sometimes funny and sometimes sad but always sincere and revealing."[16] Kristin Anderson of The Oxonian Review of Books of Balliol College, University of Oxford said, "While Persepolis’ feistiness and creativity pay tribute as much to Satrapi herself as to contemporary Iran, if her aim is to humanise her homeland, this amiable, sardonic and very candid memoir couldn’t do a better job."[17]

A paper centered around teaching Persepolis in a Middle School Classroom writes: "Teaching Persepolis had a positive impact on these students’ literacy learning, in particular their critical thinking abilities ... Using a graphic novel like Persepolis in the classroom can enable students to acquire the necessary critical literacy skills that aid them in the important tasks of reading the word and the world (Freire & Macedo, 1987).[11]"

Despite the positive reviews, Persepolis faced some attempts at censorship in school districts across the United States. In March 2013, the Chicago Public Schools controversially ordered copies of Persepolis to be removed from seventh-grade classrooms, after Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett determined that the book "contains graphic language and images that are not appropriate for general use."[18][19][20] Upon hearing about the proposed ban, upperclassmen at Lane Tech High School in Chicago flocked to the library to check out Persepolis and organized demonstrations in protest. Such action resulted in CPS reinstituting the book in their school libraries and classrooms.[21] Additionally, Kristine Mayle, a representative for the Chicago Teachers Union spoke out against the ban by Chicago Public Schools due to the existing “volatile climate surrounding the ongoing closing of fifty-four public schools in Chicago, primarily in African American and Hispanic neighborhoods.[4]” In an interview she pointed out that “The only thing I can think of is they don’t want our children reading about revolution as they’re closing our schools down”.[4]

In 2014, the book faced three different challenges across the country, which led to its placement as #2 on the ACLA’s list of “Top Ten Most Challenged Books of 2014.”[22] The first of these challenges occurred in Oregon’s Three Rivers School District, where a parent insisted on the removal of the book from its high school libraries due to the “coarse language and scenes of torture.”[23] The book ultimately remained in libraries without any restriction after school board meetings to discuss this challenge. Another case of censorship arose in central Illinois’ Ball-Chatham School District, where the parent of a senior English student stated that the book was inappropriate for the age group assigned. He also “questioned why a book about Muslims was assigned on September 11.”[23] Despite this opposition, the school board voted unanimously to retain the book both in the school and within the curriculum. The third case arose in Smithville, Texas, where parents and members of the school community challenged the book being taught in Smithville High School’s World Geography Class. They voiced concerns “about the newly-introduced Islamic literature available to students.” The school board met to discuss this issue at a meeting on February 17, 2014 after Charles King filed a formal complaint against Persepolis. The board voted 5-1 to retain the novel.[23]

In 2015, Crafton Hills College in Yucaipa, California, also witnessed a challenge to the incorporation of Persepolis in its English course on graphic novels. After her completion of the class, Tara Shultz described Persepolis as “pornography” and “garbage.” Crafton Hills administrators released a statement, voicing strong support of academic freedom and the novel was ultimately retained.[23]

Film

Persepolis has been adapted into an animated film, by Sony Pictures Classics. The film was co-directed by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud.[24] The film is voiced by Catherine Deneuve, Chiara Mastroianni, Danielle Darrieux and Simon Abkarian, among others. It debuted at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Jury Prize. The film drew complaints from the Iranian government before its debut at the festival.[25][26] The film was nominated for an Academy Award in 2007 for best animated feature.

Persepolis 2.0

Persepolis 2.0 is an "updated" version of Satrapi's story, combining her illustrations with new text about the 2009 Iranian presidential election. Only ten pages long, Persepolis 2.0 recounts the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad on June 12, 2009. Done with Satrapi’s permission, the authors of the comic are two Iranian-born artists who live in Shanghai and who give their names only as Payman and Sina.[27] The authors used Satrapi's original drawings, changing the text where appropriate and inserting one new drawing, which has Marjane telling her parents to stop reading the newspaper and instead turn their attention to the internet and Twitter during the protests. Persepolis 2.0 was published online, originally on a website called "Spread Persepolis"; an archived version is available at the Wayback Machine.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Jones, Malcolm. "'Persepolis', by Marjane Satrapi - Best Fictional Books - Newsweek 2010". 2010.newsweek.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-19. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- 1 2 Nabizadeh, Golnar (Spring–Summer 2016). "Vision and Precarity in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis". Women's Studies Quarterly. 44 – via Proquest.

- ↑ Nehl, Katie. "Graphic novels, more than just superheroes". The Prospector. Daily Dish Pro. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Otsby, Marie (2017). "Graphic and Global Dissent: Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, Persian Miniatures, and the Multifaceted Power of Comic Protest". Modern Language Association of America – via PMLA.

- 1 2 Jones, Vanessa E. (4 Oct 2004). "A Life in Graphic Detail; Iranian Exile's Memoirs Draw Readers into Her Experience: [Third Edition]". Boston Globe.

- ↑ Nel, Philip; Paul, Lissa (2011). Keywords for Children's Literature. New York: New York University Press.

- ↑ Naghibi, Nima; O'Malley, Andrew (June–September 2005). "Estranging the familiar: "East" and "West" in Satrapi's Persepolis (1)". English Studies in Canada. 31.2-3: 223 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ↑ Satrapi, Marjane; Gard, Daisy (2013). Riggs, Thomas, ed. "Persepolis." The Literature of Propaganda (1st ed.).

- ↑ "Why I Wrote Persepolis" (PDF).

- ↑ "Why I Wrote Persepolis" (PDF). greatgraphicnovels.files.wordpress.com.

- 1 2 3 Sun L. Critical Encounters in a Middle School English Language Arts Classroom: Using Graphic Novels to Teach Critical Thinking & Reading for Peace Education. Multicultural Education [serial online]. Fall2017 2017;25(1):22-28. Available from: Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 26, 2018.

- ↑ Provenzo, Eugene F. (2008). Encyclopedia of the Social and Cultural Foundations of Education. Sage Publications.

- ↑ "Visual literacy". Wikipedia. 2018-03-09.

- ↑ Satrapi, Marjane (2000). Persepolis. Pantheon Books. p. 77.

- ↑ Arnold, Andrew. "2003 Best and Worst: Comics." TIME. Retrieved on 15 November 2008.

- ↑ Arnold, Andrew. "An Iranian Girlhood. TIME. Friday 16 May 2008.

- ↑ Anderson, Kristin. "From Prophesy to Punk Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine.." Hilary 2005. Volume 4, Issue 2.

- ↑ Wetli, Patty. "'Persepolis' Memoir Isn't Appropriate For Seventh-Graders, CPS Boss Says". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen; Bowean, Lolly (15 March 2013). "CPS tells schools to disregard order to pull graphic novel". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ Gomez, Betsy. "Furor Continues Over PERSEPOLIS Removal". Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Libraries and Schools". Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom. 62 (3): 103–104. 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Top Ten Most Challenged Books Lists". Banned and Challenged Books. American Library Association. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Case Study: Persepolis". Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ↑ Gilbey, Ryan (April 2008). "Children of the revolution: a minimalist animation sheds light on the muddle of modern Iran". New Statesman – via Literature Resource Center.

- ↑ Iran Slams Screening off Persepolis at Cannes Film Festival, http://www.monstersandcritics.com

- ↑ Jaafar, Ali. "Iran decries 'Persepolis' jury prize ." Variety.com May 29, 2007

- ↑ Itzkoff, Dave. "‘Persepolis’ Updated to Protest Election," The New York Times, published 21 August 2009, retrieved 28 August 2009.

References

- Davis, Rocio G. (2005). "A Graphic Self: Comics as Autobiography in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis". Prose Studies. 27 (3): 264–279.

- Malek, Amy (2006). "Memoir as Iranian Exile Cultural Production: A Case Study of Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis Series". Iranian Studies. 39 (3): 353–380. doi:10.1080/00210860600808201.

- Hendelman-Baavur, Liora (2008). "Guardians of New Spaces: "Home" and "Exile" in Azar Nafisi's Reading Lolita in Tehran, Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis Series and Azadeh Moaveni's Lipstick Jihad". HAGAR Studies in Culture, Polity and Identities. 8 (1): 45–62.

- Bhoori, Aisha (2014). "Reframing the Axis of Evil". Harvard Political Review

Further reading

- DePaul, Amy (5 February 2008). "Man with a Country: Amy DePaul interviews Seyed Mohammad Marandi". Guernica. New York. Retrieved 21 December 2013.