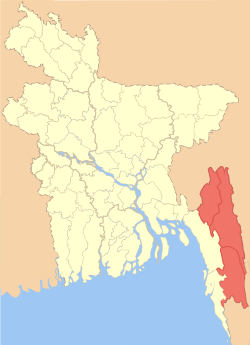

Chittagong Hill Tracts conflict

| Chittagong Hill Tracts conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Shanti Bahini insurgents, photographed on 5 May 1994. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| GOC of the 24th Infantry Division of the Bangladesh Army |

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,632 (June 1991 estimate)

| 2,000–47,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

44 (Bangladeshi claim) 500 (Shanti Bahini claim)[4] |

5,700 killed 15,432 wounded 11,892 captured and/or arrested | ||||||

|

1,552 civilians kidnapped by Shanti Bahini insurgents (757 Bengalis and 795 indigenous)[5][6] More than 3,000[7] Jumma civilians killed by security forces and settlers (See Massacres) | |||||||

The Chittagong Hill Tracts conflict was a political and armed conflict between the government of Bangladesh and the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Sanghati Samiti (United People's Party of the Chittagong Hill Tracts) and its armed wing, the Shanti Bahini, over the issue of autonomy and the land rights of Jumma people, Chakma people and the other indigenous of Chittagong Hill Tracts. Shanti Bahini launched an insurgency against government forces in 1977, when the country was under military rule, and the conflict continued for twenty years until the government and the PCJSS signed the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord in 1997.[8][9][10][11][12]

The actions carried out by the armed forces and the paramilitary groups helping them have been projected by tribals as genocide and ethnic cleansing.[13][7][14] There have been reports of mass rapes by the paramilitary Bangladesh Ansars, though these have been disputed.[15]

According to Amnesty International as of June 2013 the Bangladeshi government made "praiseworthy progress" in implementing the terms of the peace accord and in addressing the Jumma people's concerns over the return of their land. Amnesty estimate that there are currently only 900 internally displaced Jumma families.[16][17]

Background

The conflict in the Chittagong Hill Tracts dates back to when Bangladesh was the eastern wing of Pakistan. Widespread resentment occurred over the displacement of as many as 100,000 of the native peoples due to the construction of the Kaptai Dam in 1962. The displaced did not receive compensation from the government and many thousands fled to India. After the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, representatives of the Chittagong Hill Tracts who were against Bangladeshi independence such as the Chakma politician Manabendra Narayan Larma sought autonomy and recognition of the rights of the peoples of the region. Larma and other Hill Tracts representatives protested the draft of the Constitution of Bangladesh. It did not recognise the ethnic identity and culture of the non-Muslim, non-Bengali peoples of Bangladesh. The government policy recognised only the Bengali culture and the Bengali language, and designated all citizens of Bangladesh as Bengalis. In talks with a Chittagong Hill Tracts delegation led by Manabendra Narayan Larma, the country's founding leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman expressed that the ethnic groups of the Hill Tracts as citizen of Bangladesh should have the Bengali identity.[18][19] Sheikh Mujib is also reported to have threatened to forcibly settle Muslim Bengalis in the Hill Tracts to reduce the native Buddhist and Hindu peoples into a minority,which later proved to be a false allegation.[18][19][20]

The migrated hill Jummas were given with special treatment, as they were the minority after independence in 1971.[21] The rebellion by the Jummas began after the 1971 independence of Bangladesh.[22]

Insurgency

Larma and others founded the Parbatya Chhatagram Jana Shanghatti Samiti (PCJSS) as a united political organisation of all native peoples and tribes in 1973. The armed wing of the PCJSS, the Shanti Bahini was organised to resist government policies.[19][23] The crisis aggravated during the emergency rule of Sheikh Mujib, who had banned all political parties other than his BAKSAL and the successive military regimes that followed after his assassination in 1975. In 1977, the Shanti Bahini launched their first attack on a Bangladesh Army convoy.[1][19][23] It is alleged that the Indian government helped the Shanti Bahini set up bases across the border from Bangladesh.[2]

The Shanti Bahini divided its area of operations into zones and raised forces from the native people, who were formally trained. The Shanti Bahini attacked Bengali police and soldiers, government offices and personnel and the Bengali settlers in the region. The group also attacked any native believed to be opposing it and supporting the government.[24] According to government sources between 1980 and 1991, 1,180 people were killed by the Shanti Bahini, and 582 were kidnapped.[2][25]

400 Chakmas including Anupam Chakma absconded to India to evade the Bangladesh Army in 1989.[26] Chakmas dominate the Shanti Bahini.[27] Chakmas raised the insurgency as they wanted autonomy in that region.[28]

Human rights abuses against the Jumma

.jpg)

Bangladesh was under military rule for fifteen years and democracy was restored in 1990.[29] During this period there were several massacres of Jumma peoples in the CHT, the main perpetrators of these acts of mass violence being the Bangladesh armed forces.[30] The UN special rapporteur has reported on extrajudicial, arbitrary and summary executions and that he had received reports of numerous human rights violations.[31]

Massacres

- In 1980, Bangladeshi armed forces attacked the village of Kawkhali and left 300 dead.[31]

- Another massacre occurred on 3 March when the Bangladeshi armed forces killed between 3,000 and 4,000 people.[7]

- Another massacre occurred on 25 March 1981 in which settlers attacked and killed 500 people in Matiranga.[31]

- Shanti Bahini killed 13 Bengali civilians and 24 members of Bangladesh Rifles on 23 June 1981.[32]

- Another massacre occurred in 1986 in Panchari.

- Another massacre occurred in 1989 in Longudu which left 40 Jumma peoples dead and displaced a further 13,000.[33]

- Another massacre occurred in 1992 in Logang which caused the deaths of hundreds of people with reports that hundreds had been burned alive and others shot dead while trying to escape. The incident led to the EU passing a resolution requesting that Bangladesh put a halt to continued violence in the CHT.[31][34][35]

- The Naniachar massacre in 1993 led to 100 people being killed after a student demonstration was attacked by the JSS and Hill Youth Federation.[36][37]

- Another massacre took place in 1996, when 28 Bengali Woodcutters were killed by Members of the Shanti Bahini.[38]

Rapes

Between 1981 and 1994 it is estimated that 2,500 Jumma women had been raped by Bangladesh armed forces and in 1995 it was estimated that of over 94% of rapes between 1991 and 1993 had been by the Bangladesh armed forces, with allegations that 80% of those raped were Jumma. According to Kabita Chakma and Glen Hill, the sexual abuse against Jumma women is endemic.[39] During the conflict, the security forces had used a deliberate strategy of rape, torture, arbitrary arrests, mass imprisonment and kidnapping against the Jumma.[40]

Recent Developments

The accords of the peace treaty have yet to be fully implemented which has resulted in the region remaining heavily militarised and mass inward migration continuing. Human rights violations continue with arbitrary arrests, killing and rapes occurring and human rights activists are targeted for questioning and arrests.[41] According to a report from the Asian Centre for Human Rights on 26 August 2003 the UPDF in conjunction with tribals planned and launched an attack on ten villages. Hundreds of people were displaced and it is estimated that ten women, some who were Jumma were raped. It was reported that a nine-month-old child was strangled after it was grabbed from its grandmother who the settlers raped.[42]

As yet the Jumma peoples have not been given constitutional recognition and are known as "backward segments of the population"[43]

Government reaction

At the outbreak of the insurgency, the Government of Bangladesh deployed the army to begin counter-insurgency operations. The then-President of Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman created a Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Board under an army general to address the socio-economic needs of the region, but the entity proved unpopular and became a source of antagonism and mistrust amongst the native people against the government. The government failed to address the long-standing issue of the displacement of people, numbering an estimated 100,000 caused by the construction of the Kaptai Dam in 1962.[44] Displaced peoples did not receive compensation and more than 40,000 Chakma tribals had fled to India.[44] In the 1980s, the government began settling Bengalis in the region, causing the eviction of many natives and a significant alteration of demographics. Having constituted only 11.6% of the regional population in 1974, the number of Bengalis grew by 1991 to constitute 48.5% of the regional population.

In 1989, the government of then-president Hossain Mohammad Ershad passed the District Council Act created three tiers of local government councils to devolve powers and responsibilities to the representatives of the native peoples, but the councils were rejected and opposed by the PCJSS.[11]

Peace accord

Peace negotiations were initiated after the restoration of democracy in Bangladesh in 1991, but little progress was made with the government of Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia, the widow of Ziaur Rahman and her Bangladesh Nationalist Party.[45] Fresh rounds of talks began in 1996 with the newly elected prime minister Sheikh Hasina Wajed of the Awami League, the daughter of Sheikh Mujib.[45] The peace accord was finalised and formally signed on 2 December 1997.[12]

The agreement recognised the special status of the hill residents.[11] Chakma rebels were still in the Chittagong Hill Tracts as of 2002.[46]

Chakmas also live in India's Tripura state where a Tripuri separatist insurgency is going on.[47]

See also

References

- 1 2 Bangladeshi Insurgents Say India Is Supporting Them – New York Times

- 1 2 3 A. Kabir. "Bangladesh: A Critical Review of the Chittagong Hill Tract (CHT) Peace Accord". Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Does Peacekeeping Work?. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Hazarika, Sanjoy (11 June 1989). "Bangladeshi Insurgents Say India Is Supporting Them". The New York Times.

- ↑ Chittagong Hill Tract : Peace & Situation Analysis by Maj. Gen. (Retd.) Syed Md. Ibrahim

- ↑ Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Thomson Reuters Foundation". Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Jonassohn, Kurt; Karin Solveig Björnson (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction. p. 257. ISBN 1560003146.

- ↑ Rashiduzzaman, M. (July 1998). "Bangladesh's Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord: Institutional Features and Strategic Concerns". Asian Survey. University of California Press. 38 (7): 653–70. doi:10.1525/as.1998.38.7.01p0370e. JSTOR 2645754.

- ↑ "Bangladesh peace treaty signed". BBC News. 2 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ↑ "Chittagong marks peace anniversary". BBC News. 2 December 1998. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 Mohsin, Amena (2012). "Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord, 1997". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs Archived 8 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Arens, Jenneke (2010). Genocide of indigenous Peoples. Transaction. p. 123. ISBN 978-1412814959.

- ↑ Begovich, Milica (2007). Karl R. DeRouen, Uk Heo, ed. Civil Wars of the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 166. ISBN 978-1851099191.

- ↑ Jonassohn, Kurt; Karin Solveig Björnson (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction. p. 258. ISBN 1560003146.

- ↑ International, Amnesty (12 June 2013). "Bangladesh: Indigenous Peoples engulfed in Chittagong Hill Tracts land conflict". Amnesty International.

- ↑ Erueti, Andrew (13 June 2013). "Amnesty criticises Bangladeshi government's failure to address indigenous land rights". ABC.

- 1 2 Nagendra K. Singh (2003). Encyclopaedia of Bangladesh. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 222–223. ISBN 81-261-1390-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Bushra Hasina Chowdhury (2002). Building Lasting Peace: Issues of the Implementation of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Accord. University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. Archived from the original on 1 September 2009.

- ↑ Shelley, Mizanur Rahman (1992). The Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh: The untold story. Centre for Development Research, Bangladesh. p. 129.

- ↑ Mohaiemen, Naeem (15 November 2012). "In Bangladesh, Stranded on the Borders of Two Bengals". The New York Times.

- ↑ Crossette, Barbara (8 July 1989). "Khagrachari Journal; Seeking Happiness High in the Hills". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Nagendra K. Singh (2003). Encyclopaedia of Bangladesh. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 229. ISBN 81-261-1390-1.

- ↑ Kader, Rozina (2012). "Shanti Bahini". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Human rights in the Chittagong Hill Tracts; February 2000; Amnesty International.

- ↑ Hazarika, Sanjoy (8 July 1989). "Under Cover of Darkness, 400 Flee to Haven in India". The New York Times.

- ↑ Crossette, Barbara (26 June 1989). "Bangladesh Tries to Dampen Ethnic Insurgency With Ballots". The New York Times.

- ↑ Binder, David; Crossette, Barbara (7 February 1993). "As Ethnic Wars Multiply, U.S. Strives for a Policy". The New York Times.

- ↑ Corporation, British Broadcasting (16 July 2013). "Bangladesh profile". BBC.

- ↑ Roy, Chandra (2005). Ghanea-Hercock, Nazila; Xanthaki, Alexandra; Thornberry, Patrick, eds. Minorities, Peoples and Self-Determination: Essays in Honour of Patrick Thornberry. Martinus Nijhoff. p. 123. ISBN 978-9004143012.

- 1 2 3 4 Roy, Rajkumari Chandra (2000). Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 123. ISBN 978-8790730291.

- ↑ The Election Archives. Shiv Lal. 2018-01-29. p. 218.

- ↑ D'Costa, Bina (2012). Aspinall, Edward; Jeffrey, Robin; Regan, Anthony, eds. Diminishing Conflicts in Asia and the Pacific: Why Some Subside and Others Don't. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0415670319.

- ↑ Roy, Rajkumari Chandra (2000). Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 222. ISBN 978-8790730291.

- ↑ Arens, Jenneke (2010). Samuel Totten, Robert K. Hitchcock, ed. Genocide of indigenous Peoples. Transaction. p. 141. ISBN 978-1412814959.

- ↑ Jensen, Marianne (2001). Suhas Chakma, Marianne Jensen, ed. Racism Against Indigenous Peoples. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 209. ISBN 978-8790730468.

- ↑ Roy, Rajkumari Chandra (2000). Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 124. ISBN 978-8790730291.

- ↑ "Army pullout from CHT opposed by settlers". archive.thedailystar.net. The Daily Star. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ Chakma, Kabita; Glen Hill (2013). Kamala Visweswaran, ed. Everyday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle East. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0812244878.

- ↑ Begovich, Milica (2007). Karl R. DeRouen, Uk Heo, ed. Civil Wars of the World (1st ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 169. ISBN 978-1851099191.

- ↑ Wessendorf, Kathrin (2009). The Indigenous World 2009. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-87-91563-57-7.

- ↑ Chakma, Suhas (2003). Starvation, Rape and Killing of Indigenous Jumma Children (PDF). Asian Centre for Human Rights. p. 4.

- ↑ Wessendorf, Kathrin (2011). The Indigenous World 2011. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 328. ISBN 978-87-91563-97-3.

- 1 2 "The construction of the Kaptai dam uproots the indigenous population (1957–1963)". Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- 1 2 Majumder, Shantanu (2012). "Parbatya Chattagram Jana-Samhati Samiti". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Samrat (21 August 2012). "The "Imaginary Line" that Divides India and Bangladesh". The New York Times.

- ↑ Hazarika, Sanjoy (13 August 1988). "India and Tribal Guerrillas Agree to Halt 8-Year Fight". The New York Times.